For citation, please use:

Diabat, K.S., Aljarwan, M.K. and Suleiman, M., 2024. The GCC-SCO Relationship Dynamics. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(4), pp. 105–116. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-4-105-116

For a long time, the Gulf remained far from the direct interests of the SCO, mainly focused on Central Asia. However, as the international landscape began to change, the relations between the SCO and the GCC began to transform. The political, economic, and security interests of the SCO and GCC states overlap in the Gulf, which has thus seen growing cooperation between the two associations. Five GCC countries (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, the Emirates, and Bahrain) have been granted Dialogue Partner status in the SCO, which is increasingly seen as a potential counterbalance to NATO and the collective West.

The Gulf’s Significance to the SCO

The Gulf is a region of great geostrategic importance. First, it is significant for global maritime trade, as many sea routes pass through the Gulf, the Arabian Sea, and the Red Sea. Second, it has rich oil and gas deposits of significance to the global economy. And third, its proximity to Middle East conflict sites makes it significant to global security (Al-Musfir and Suleiman, 2022).

However, while the SCO’s leaders, Russia and China, have long sought to expand their influence in the Middle East, and the Gulf in particular, this ambition always collided with the GCC states’ informal alliance with the West since the Gulf War (Bin Huwaidin, 2002). The SCO only appeared in official GCC documents in 2007, when a policy paper was presented at the Beijing meeting of GCC members’ ambassadors, highlighting the importance for the SCO of security and stability in Asia, and urged the GCC states to consider joining it (Ahmed, 2018).

Nevertheless, China and Russia have pursued every opportunity for engagement with the Gulf (Emirates Policy Center, 2022). Shortly after the USSR’s collapse, China and Russia intensified their visits to the Gulf states, developing bilateral relations based on mutual interests (Al-Obaidi, 2013). They revived agreements with their traditional allies (Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Sudan, and Algeria), and built relations with other Middle Eastern countries, including those of the GCC (Zidane, 2013). From November 2011 to July 2023, six meetings of foreign ministers produced memoranda of understanding on strategic dialogue and enhanced cooperation (Joint Statement, 2023).

It might seem that Russia’s support of Syria and Iran, and opposition to the Saudi intervention in Yemen, would have created a rift between Russia and the Gulf states, especially Saudi Arabia and Qatar (which Russia sees as supporting the Sunni radical movement in Syria and even in Russia). However, these differences did not prevent Russia and the Gulf states from finding common ground on energy production and technology.

Moscow also maintained neutrality during the 2017 Gulf crisis (Frolovsky, 2018). With the start of Russia’s Special Military Operation, the GCC called for a diplomatic resolution, but its members’ positions differed drastically: Kuwait and Qatar tended to support Ukraine, Saudi Arabia and the UAE cautiously aligned with Russia, while Bahrain and Oman distanced themselves from both sides (Fayed, 2022).

China’s relations with the GCC’s members were long hindered by ideological differences, with diplomatic relations being established only in the 1980s, growing as China became a net importer of oil starting in 1993 (Calabrese, 2004). As turmoil spread in the Middle East in the 2000s, China deepened its partnerships with the Arab states and the GCC. As Chinese economic activity expanded around the world, China-Gulf relations acquired a political and even security-related dimension. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) posits the logistical importance of the Middle East and the Gulf especially (Fulton, 2019). Within the BRI, China intends to develop cooperation with Middle Eastern countries in energy, trade, investment, and logistics (Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2016). Moreover, as the U.S.’s regional influence has waned since its 2011 withdrawal from Iraq, China has also adopted an increasingly active role, illustrated by state visits and summits in 2016 and 2022.

The Gulf region is also highly important to India, a relatively new member of the SCO. The GCC supplies about 50% of New Delhi’s oil needs (Ahmed, 2022). It is also a major source of investment in India (as well as Pakistan and Central Asian republics) (General Secretariat, 2023).

Generally, the SCO’s members have the following objectives in cooperation with the GCC states:

- secure oil supplies (e.g., from military conflicts or Western pressure);

- fight common threats such as drug trafficking, arms trafficking, piracy, and terrorism;

- raise the SCO’s international status, especially via full membership of the wealthy Gulf states;

- ease international concerns about the SCO’s global expansion. Chinese/Russian partnerships with the GCC’s members enhance the legitimacy of Chinese/Russian presence in the region;

- strengthen influence in the Middle East and Gulf. The SCO’s ‘Turn to the East’ weakens U.S./Western dominance (Hamiaz, 2020));

- stabilize the Middle East through alignment with both the GCC states and Iran and through direct promotion of Arab-Iranian rapprochement. (See China’s support of the 2023 Saudi-Iranian rapprochement.)

The SCO’s Significance to the Gulf

U.S. relations with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the GCC as a whole have recently soured, partly due to the U.S.’s weaponization of aid, its efforts to force GCC states to boost oil production in 2022 (Schiavi, 2023), its allegations of Gulf states’ lack of human rights and democracy, and its general interference in their internal affairs.

The GCC states adhere to the SCO’s discourse of sovereignty, diversity of modernization policies, multipolarity, and solidarity of the Global South against Western hegemony. Witnessing the gradual transfer of economic and technological power from West to East, and the decline of U.S. interest in the Middle East, the GCC states realize the importance of diversifying their external partnerships (Cheng, 2016), especially to politically, economically, and militarily powerful states like the SCO’s leaders: China, India, and Russia. The permanent membership of China and Russia in the UN Security Council could facilitate the resolution of some Arab and Gulf issues. The GCC states could benefit from Russia’s enormous defense manufacturing capacities and from coordination with Moscow on energy issues. Indian expertise in electronic services and software, and China’s huge investment potential (Lo, 2017), could also be economically beneficial, especially as Gulf states seek to diversify away from reliance on oil (Schiavi, 2023).

Fear of marginalization in Eurasian affairs, and of Iran’s successful accession to the SCO, has also clearly pushed the GCC states to follow suit. As Dialogue Partners or full members, they can limit Iranian influence over the SCO, which is important so long as various disputes (e.g., over the Three Islands or Iran’s nuclear program) remain unresolved.

Growing Economic Ties

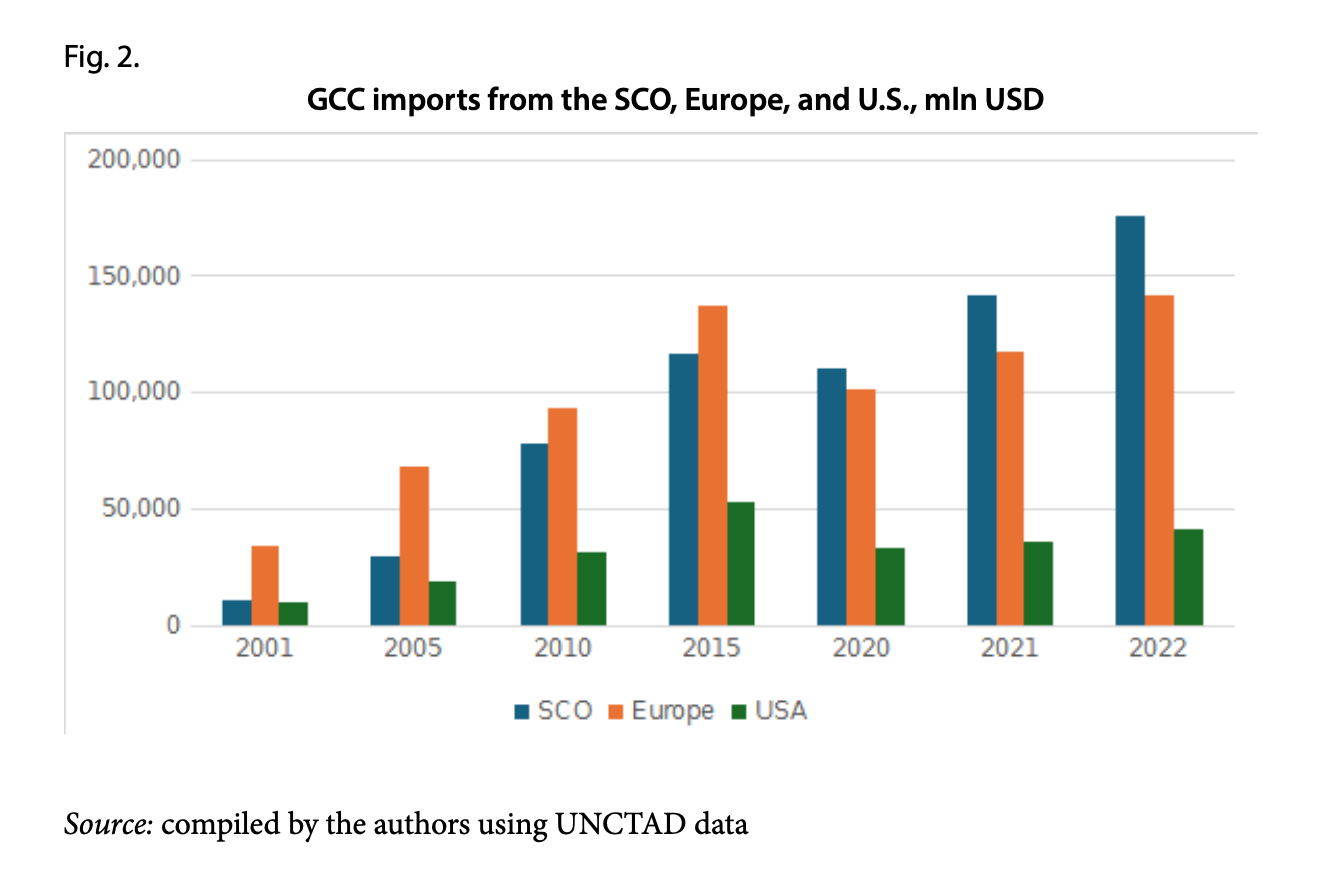

The data presented below illustrates the development of GCC economic relations with the SCO and Western countries over the last two decades.

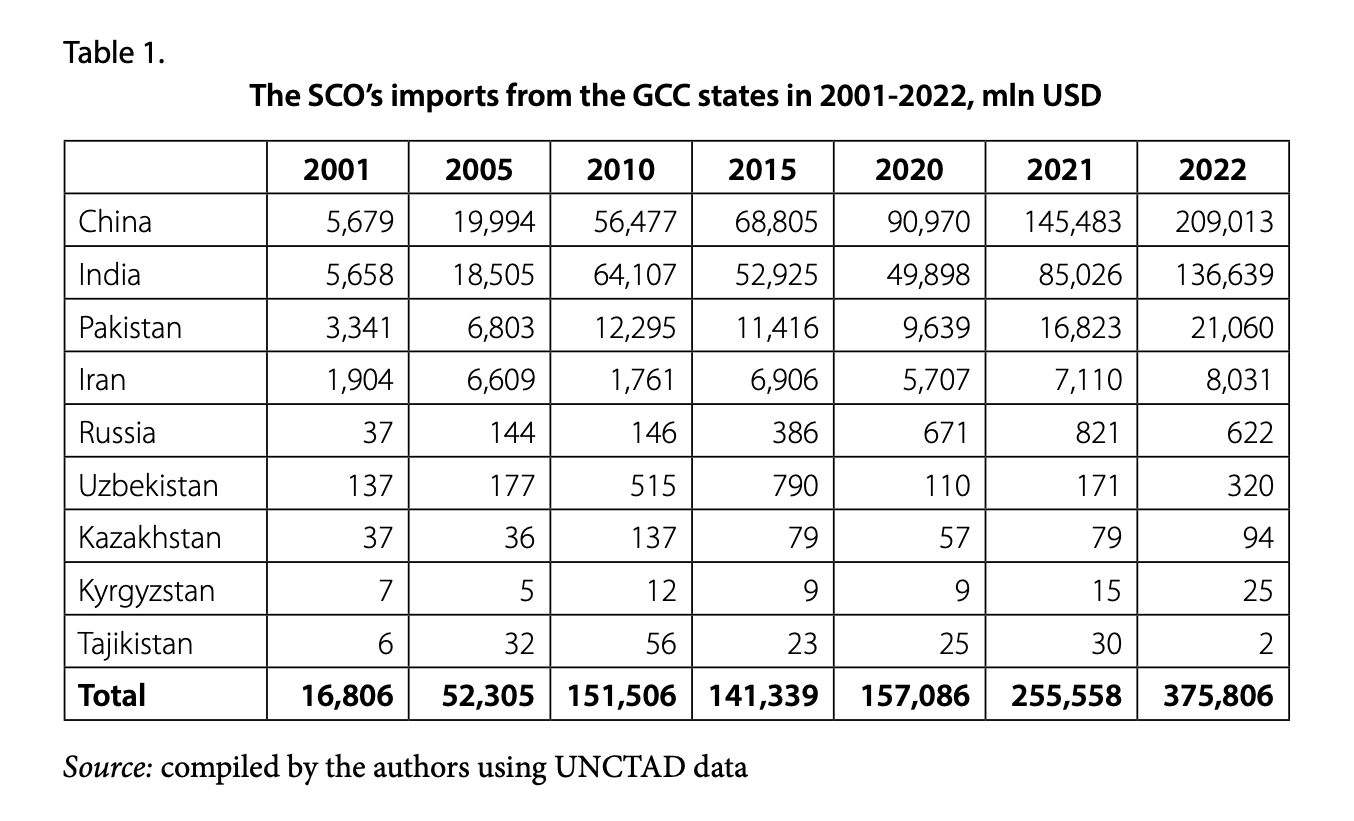

The SCO members’ imports from the GCC states have increased significantly, from $16.80 billion in 2001 to approximately $37.58 billion in 2022, i.e., with China and India accounting for the largest share (92%) (Table 1).

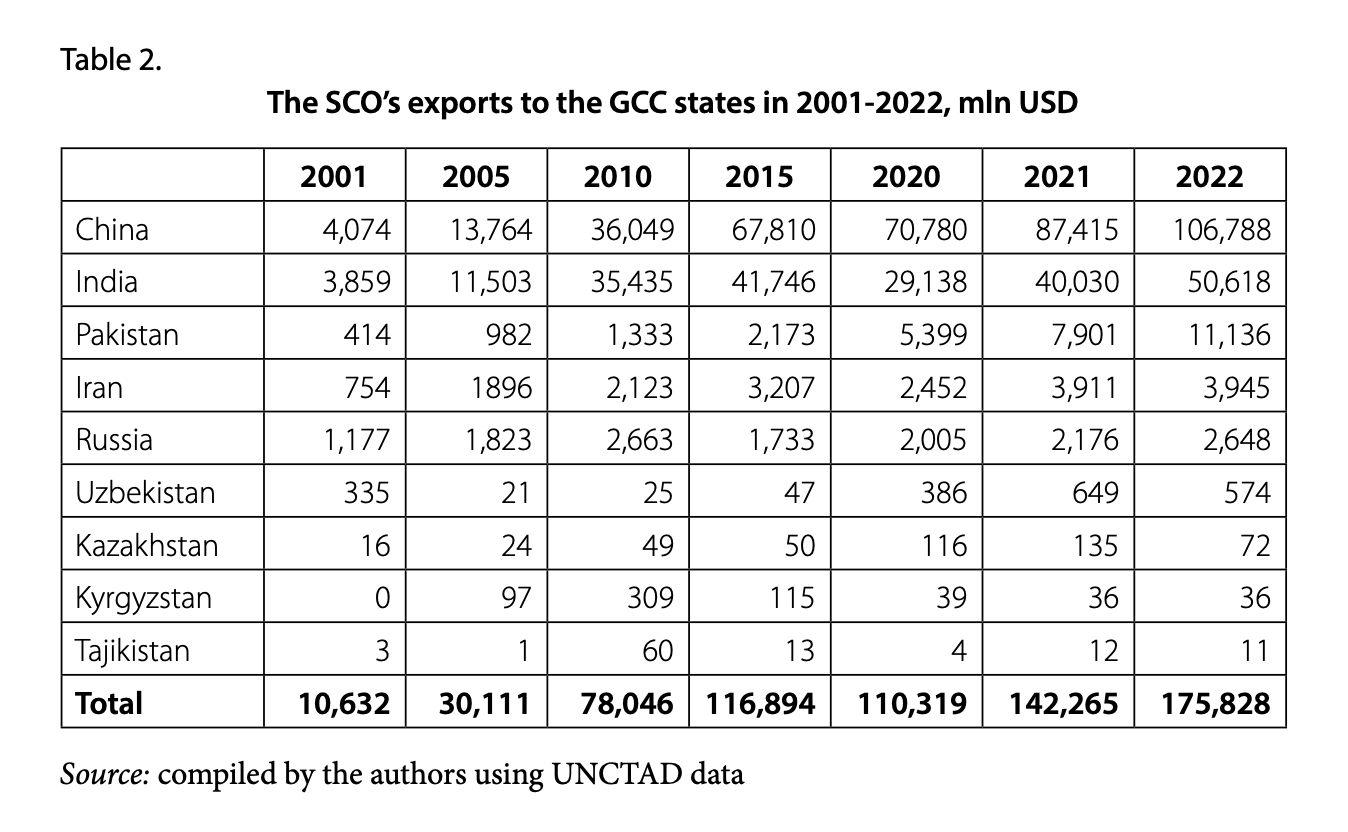

The exports of the SCO members to the GCC also witnessed a significant increase, from $10.632 billion in 2001 to $175.8 billion in 2022 (see Table 2). China and India accounted for the largest share in the exports from the Gulf countries, which jointly amounted to about 90%. The largest share in these exports (mostly industrial products and electronic devices) went to the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

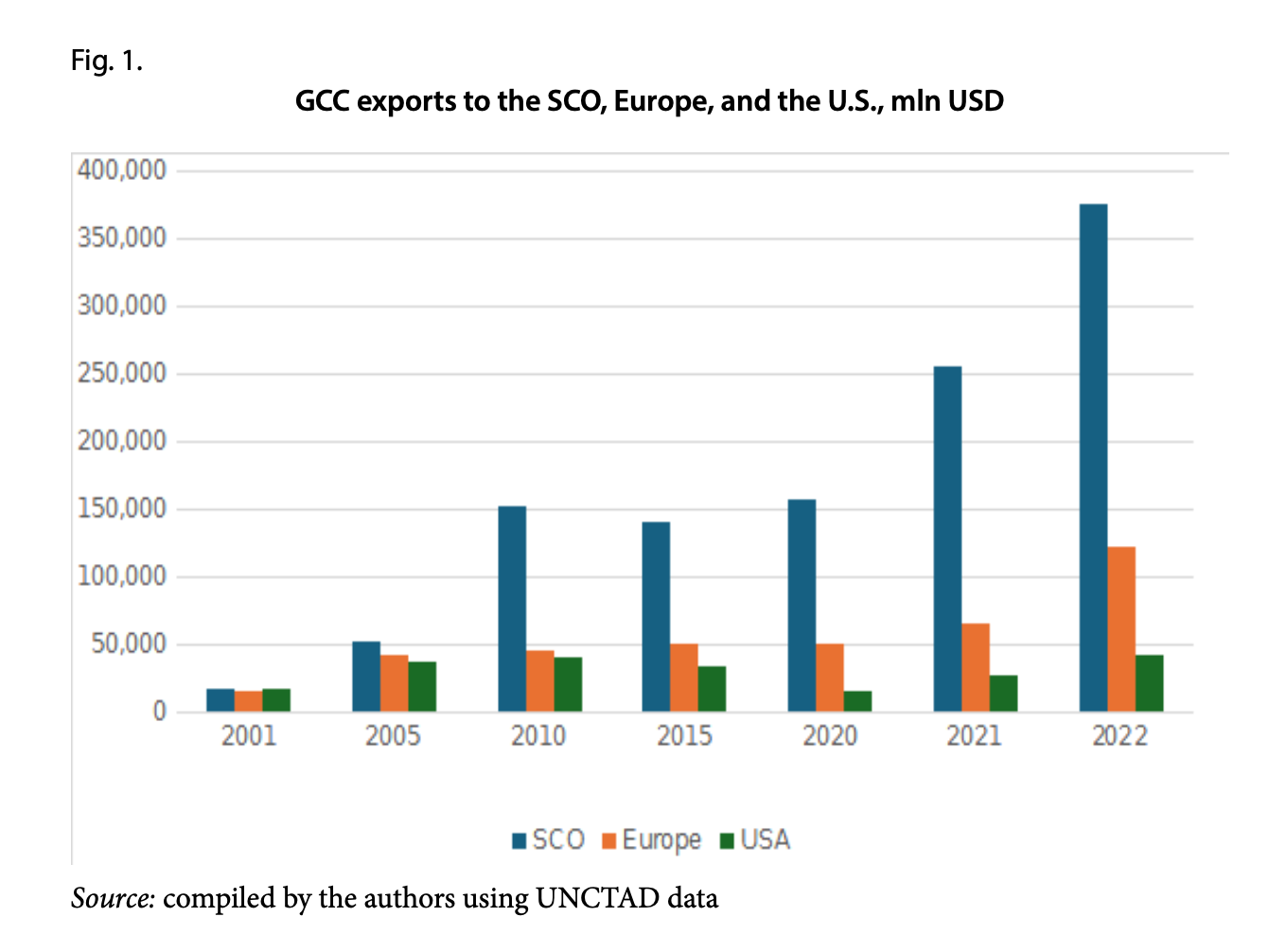

The SCO—especially China and India—has surpassed Europe and the U.S. in trade with the GCC.

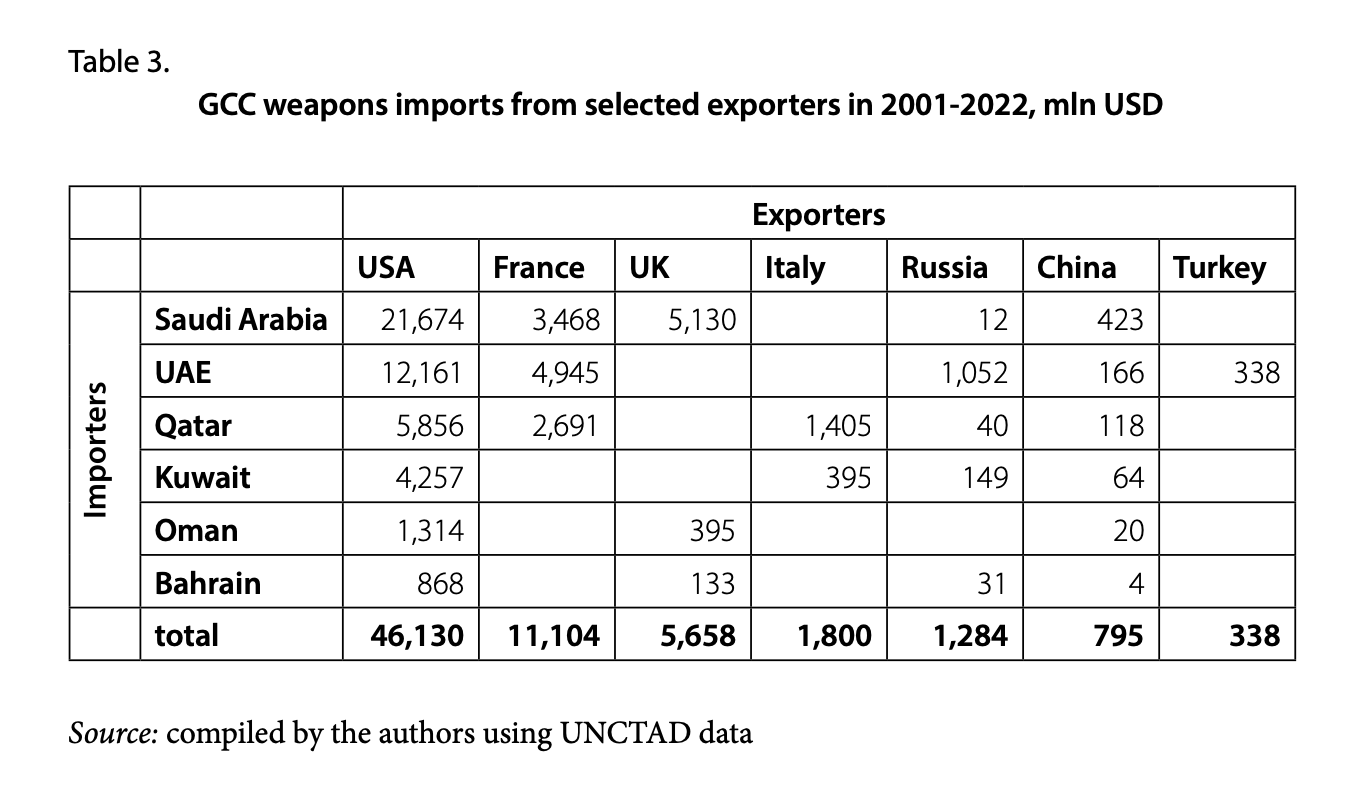

However, the GCC states remain overwhelmingly dependent upon Western supplies of arms and military equipment (Table 3).

GCC-SCO Political Alignment: Opportunities and Challenges

Global and regional changes have also contributed to the GCC and SCO states’ political alignment.

Firstly, as stated above, the SCO’s members, above all China and Russia, are trying to fill the vacuum left by the U.S. in the Middle East.

Second, SCO-Gulf relations are not burdened by a colonial past. To the contrary, during the Cold War, China and the USSR supported various Arab states in their struggle against Western colonialism. Relations are also free from disagreements about internal political systems, and all parties consistently reject Western pressure concerning human rights and value issues.

Thirdly, the SCO and GCC states have a common vision of the international system. They share dissatisfaction with Western and U.S. interference in internal affairs and dominance in global decision-making. They stand for a multipolar order resisting U.S. hegemony (Hamiaz, 2020), as expressed in documents such as the 2022 Samarkand Statement and forums such as the 2022 Saudi-Chinese Summit (Summit of SCO, 2022; Riyadh Summit Statement, 2022).

Fourthly, the GCC and SCO states have political, military, and economic resources that could contribute to Asia-Gulf integration. While China and Russia have immense military capabilities and nuclear arsenals (see SIPRI, 2023) that could contribute to building a structure providing security to all member states (Bishkek Declaration, 2007), the GCC’s huge oil reserves are crucial to the rising economies of Asia, especially China and India.

And finally, Russia and China have the ability to contain U.S. hegemonistic behavior. For instance, their UNSC voting on the Gaza war has been welcomed by Arab countries, dissatisfied with the West’s pro-Israel approach.

However, the SCO and GCC states face many internal and external challenges to their alignment.

The most important internal challenge is the lack of cohesion within the SCO and (especially since the 2017 Gulf crisis) within the GCC, inter alia due to their ideological and cultural heterogeneity. There is even some competition between SCO members for influence in the Gulf. Both organizations are also highly unequal in terms of their members’ capabilities: China, Russia, and India predominate within the SCO, and Saudi Arabia and the UAE within the GCC, which can instill apprehension in smaller members. There is also great inequality between the SCO’s main economic actors, China and India, and the GCC states, whose lack of industry could lead to a new colonial-like dependence upon China and India (Cheng, 2016).

As for the external challenges to GCC-SCO partnership, many of their member-states have close economic relations with the West and would prefer to stay clear of its confrontation with Russia and China. Central Asian countries will not risk losing Western aid, which they consider important for their development and modernization (Yandas, 2005). And the GCC states are concerned by the relations of China, India, and Russia with Iran and Israel. For instance, Iran’s trade with China and India reached nearly $30 billion and $11 billion, respectively, in 2022 (United Nations Reports, 2022), and GCC states suspect China, Russia, and North Korea of providing Iran with ballistic missiles (Cheng, 2016). Israel’s trade with China and India reached approximately $20 billion and $11 billion, respectively, in 2022. The GCC states’ future relations with the U.S. will also affect their relations with the SCO. The U.S. has been—and remains—their most important security partner (Cheng, 2016). China and Russia are unlikely to replace it in the foreseeable future, as they are currently content with expanding their economic and diplomatic influence in the Middle East.

* * *

The GCC’s turn east towards the SCO is prompted by the SCO states’ increasingly pivotal role in the international system. The GCC states seek to diversify their political, economic, and security relations, and to balance between the SCO and Western states. The growing economic relations between the GCC and SCO states may accelerate their alignment. However, the GCC’s alignment with China and Russia in the security sphere is slowed by the legacy of the Gulf countries’ informal alliance with the U.S. and other Western states, which are likely to retain priority in the GCC’s strategies. The Gulf states are thus limited in their ability to maneuver within, and take advantage of, the international environment.

Ahmed, G.K., 2018. GCC Countries Membership in the SCO: Challenges and Prospects. Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, 12(4), pp. 533-544.

Ahmed, T., 2022. The Shanghai Organization and the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: A Call for New Horizons and the Creation of Ways for Regional Cooperation. Opinions on the Gulf Magazine, Gulf Research Centre, 180, pp. 29-37.

Al-Musfir, M. and Suleiman, M., 2022. Gulf Studies: Examining History, State and Society. Doha: Dar Al Sharq.

Bin Huwaidin, M., 2002. China’s Relations with Arabia and the Gulf (1949–1999). London: Routledge.

Calabrese, J., 2004. Dragon by the Tail: China’s Energy Quandary. Middle East Institute, 23 March. Available at: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/46278/calabrese304.pdf [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Cheng, Joseph Y.S., 2016. China’s Relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council States: Multilevel Diplomacy in a Divided Arab World. China Review, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. 16(1), pp. 35-64.

Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2016. China’s Policy Document towards Arab Countries. Available at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/ara/zxxx/201601/t20160119_9598170.html [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Bishkek Declaration, 2007. Bishkek Declaration of the Heads of the Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. CSTO. Available at: www.odkb.gov.ru/start/index-engl.htm [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Emirates Policy Center, 2022. Aboard the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Gulf Countries Look East. EPC, 5 October. Available at: https://epc.ae/en/details/brief/aboard-the-shanghai-cooperation-organization-gulf-countries-look-east [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Fayed, A., 2022. Why Did the UAE Avoid Condemning Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine in the Security Council? Al Jazeera Net, 1 March. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.net/midan/reality/politics/2022/3/1 [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Frolovsky, D., 2018. Understanding Russia-GCC Relations. In: Russia’s Return to the Middle East: Building Sandcastles? Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS). Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep21138.13.pdf [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Fulton, J., 2019. China’s Changing Role in the Middle East. Atlantic Council [online]. Available at: https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/AtlanticCouncil_Chinas_Changing_Role_in_the_Middle_East.pdf [Accessed 6 May 2024].

General Secretariat, 2023. Final Statement of the Gulf Cooperation Council and Central Asian Summit. General Secretariat of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Available at: https://www.gcc-sg.org/ar-sa/MediaCenter/NewsCooperation/News/Pages/news2023 -10-20-1.aspx [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Hamiaz, S., 2020. Russian-Chinese Cooperation to Confront American Hegemony: The Shanghai Organization as a Model. Algerian Review of Security and Development, 9(2), pp. 157-167. Available at: https://www.asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/119067 [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Joint Statement, 2023. Joint Statement of the 6th Russia–GCC Joint Ministerial Meeting for Strategic Dialogue. The MFA of the RF, 12 July. Available at: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/rso/1896567/ [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Lo, Bobo, 2017. New Order for Old Triangle? The Russia-China-India Matrix. Russie. Nei.Visions, IFRI, 100. Available at: https://www.ifri.org/en/publications/notes-de-lifri/russieneivisions/new-order-old-triangles-russia-china-india-matrix [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Schiavi, F.S., 2023. The SCO Expansion in the Gulf: A New Centre of Attraction for the Middle East? Orient XXI. Available at: https://orientxxi.info/magazine/the-sco-expansion-in-the-gulf-a-new-centre-of-attraction-for-the-middle-east,6583 [Accessed 6 May 2024].

SIPRI, 2023. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Yearbook. The Military Report. SIPRI. Available at: www.sipri.org/yearbook [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Riyadh Summit Statement, 2022. Statement of the Riyadh Summit for Cooperation and Development between the GCC and the People’s Republic of China. 9 December. Available at: https://www.mofa.gov.sa/en/ministry/statements/Pages/Statement-of-the-Riyadh-Summit-for-Cooperation-and-Development-between-the-GCC-and-the-People%27s-Republic-of-China.aspx [Accessed 20 August 2024].

Yandas, O., 2005. Emerging Regional Security Complex in Central Asia: Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and Challenges of the Post 9-11 World. Master’s Thesis. Available at: https://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12606201/index.pdf [Accessed 6 May 2024].

Zidane, N., 2013. Russia’s Role in the Middle East and North Africa from Peter the Great to Vladimir Putin. Arab House of Science Publishers: Beirut.