By the middle of the 21st century Asia may well account for half of the global GDP, trade, and investment (Asian Development Bank, 2011, p. 11). With this in mind, many suggested calling it “the Asian century.” However, will dynamic economic development be sufficient for the Asian continent’s political and cultural leadership on the global scene? This article is an attempt to provide an answer to this question with regard to filmmaking—an industry that plays an important role in the cultural life of contemporary humanity and in world politics.

While the economic importance of the film industry is universally recognized (with film markets in some countries estimated at billions of dollars), its political significance is less obvious to the public at large. Nonetheless, events such as a film from a specific country receiving an Academy Award are a worthy subject for discussion by international relations scholars (see, for example, Purushotoman, 2010).

The relevance of this topic is further borne out by the fact that the film industry is undergoing rapid transformation: the market of “streaming media” (which allow subscribers to view selected entertainment content on the Internet for a monthly subscription fee), such as Netflix, is growing at an extremely fast pace. Understanding how these processes affect the Asian film industry is also necessary to answer the question: Will Asia be able to claim leading positions in the global film industry in the 21st century?

To study the intricate, complex links between the economy, politics and the sphere of aesthetics and meanings in modern cultural industries (which include cinema) one can choose from many theoretical approaches that rely on the methods of various research disciplines: the “economics of culture,” cultural sociology, communication research, etc. A rather detailed description of cultural productions and an overview of research approaches have been proposed by S. Wang and his colleagues (Wang et al., 2020). This article is based on the approach suggested by media researcher D. Hesmondhalgh, who emphasizes the importance of “symbolic creativity” for cultural industries: cultural production requires special, creative effort to make a special kind of product, “texts” or “cultural artifacts” that are valued primarily for their meaning (Hesmondhalgh, 2018, pp. 18, 28).

Hesmondhalgh’s approach, which the author himself characterizes as based on the theory of political economy (Hesmondhalgh, 2018, p. 23), provides an insight into the organizational specifics and factors of commercial success of businesses operating in cultural industries. Hesmondhalgh notes that cultural production is characterized by high fixed and low variable costs, for which reason cultural industries are strongly focused on maximizing the audience (2018, p. 40). Analyzing the reasons for the U.S. dominance in the world markets of popular culture, he identifies two main factors: “the size and nature of the domestic market” and the active role of the state (Op. cit., p. 290). Using Hesmondhalgh’s approach, the present study of the film industry in Asia also focuses on these factors, which allows uncovering the relationship between economic efficiency of the film industries of certain countries and its socio-cultural and political effects.

To answer the question in focus, the following tasks have been set (they correspond to the sections of the main part of this article):

- To show the importance of the film industry for world politics, specifically for the Asian countries’ foreign policy strategies;

- To outline the current position of Asian countries in the world film industry;

- To reveal some of the socio-cultural factors that contribute to the dominance of Western countries in cinematography and their use of cinema as a soft power resource;

- To show the pace of digital transformation of the global film industry.

- To analyze the current state and prospects of the film industry in Asian countries that take prominent positions in terms of the size of the national film market.

To show the transformational processes in the modern film industry and the dynamics of the Asian continent’s role in it, the study uses the statistical data available mostly from the Statista Internet portal and the UNESCO database.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE FILM INDUSTRY FOR WORLD POLITICS

In recent years, both scholars and practitioners of international relations increasingly often make use of concepts that are employed mostly in studying countries’ cultural influence, such as: ‘cultural diplomacy,’ ‘noopolitics,’ and ‘soft power.’ This phenomenon seems to reflect the growing certainty about the great role that culture plays in global affairs in the modern world: “the current information revolution is changing the nature of power” (Nye, 2014, p. 19). Among the approaches crucial to understanding this trend, the concept of ‘soft power’ proposed by Nye has become the most influential one. (Nye understands soft power as “the ability to affect what other countries want” that is based on intangible resources (Nye, 1990, pp. 166-167)).

Today, “a major state without a soft power strategy… has become the exception” (Roselle, Miskimmon and O’Loughlin, 2014, p. 71). Very often, policies intended to increase the cultural influence of countries, are closely linked to their national strategies for the development of “creative industries” (cinema, video games, publishing business, etc.), which are basically aimed at increasing the export of relevant products. This also applies to Asian countries, many of which seek to use popular culture as a resource for political influence. Film production and the television drama industry are part of the soft power strategy employed by countries as diverse in geography, economic potential and cultural traditions as Turkey (Anaz and Ozcan, 2016), the United Arab Emirates (Saberi, Paris and Marochi, 2018), China (Su, 2010), India (Thussu, 2016), etc.

Active efforts by Asian countries to build up soft power have been compared in the academic literature to an arms race (Hall and Smith, 2013, p. 1). Governments get involved in this race not only in order to strengthen the position of their countries on the international political scene, but also to respond to similar actions taken by other countries (Hall and Smith, 2013, pp. 10-11).

As has been mentioned above, the present research follows D. Hesmondhalgh’s approach to studying culture. According to Hesmondhalgh, the consumption of “cultural artifacts” implies interpretation: they “influence us,” “provide us with a coherent view of the world,” and “help create our identity” (2018, pp. 16, 28). This approach is close to the concept of “strategic narratives,” which makes it possible to use it for analyzing the role of cultural industries in world politics. The concept of strategic narratives implies that soft power depends on “the ability to create consensus around shared meaning” (Roselle, Miskimmon and O’Loughlin, 2014, p. 72). Narratives that are “a power resource” “explain the world” and characterize the positions in it of various actors, such as states (Op cit., pp. 74, 76). Producers of cultural goods offer their audience a certain picture of the world, thereby contributing to the creation of appropriate “strategic narratives” and, consequently, strengthening the position of certain countries on the international scene. Cinematography, which is called “the most significant cultural industry in terms of… symbolic influence” (Vlassis, 2016, p. 483), has a particularly important potential for attaining this goal.

So, the relationship between economic wealth, soft power and the cultural influence of countries can be explained as follows.

Cultural industries embody and convey these ideas to the people of other countries, that is, “materialize soft power” (Su, 2010, p. 317). The country’s economic success boosts the domestic markets of cultural goods, which helps promote the expansion of its cultural products abroad, and, consequently, multiply its cultural and political influence.

It should be noted that since works of culture have a symbolic, “meaningful” component, and its consumption implies interpretation, it is scarcely possible to make a precise quantitative assessment of the growth of a country’ influence obtained through cultural production. According to G. Rawnsley, in assessing the cultural sources of soft power it is easy to estimate their output, while its effects are extremely hard to gauge (Rawnsley, 2012, p. 129). Also, as economist and philosopher Ludwig von Mises noted quite correctly, the efforts and achievements of creative innovators cannot be assessed in the process of analysis as a means of production: no one, except Dante and Beethoven, would have been able to create The Divine Comedy or The Ninth Symphony, regardless of the demand or incentives from the state for creating such works (von Mises, 1963, pp. 139-140). In other words, a state’s strategy to promote national culture cannot guarantee results; it only provides conditions for creating cultural artifacts and channels for their dissemination.

However, this approach, which highlights the distinctive features of cultural industries, does not mean that it attaches little importance to the entrepreneurial decisions and government strategies that shape these industries. On the contrary, the format and technical characteristics of works of culture, determined by commercial considerations and technological possibilities, set a certain framework for “creative workers” that influences the meaning of their products. In this respect, this paper agrees with Keith Negus’ observation that “industry produces culture” (Negus, 1999, p. 490). The problem of how political actors can influence the artistic value of the cultural industry (film festivals, for instance) will be discussed below.

ASIAN COUNTRIES IN the WORLD FILM INDUSTRY

We can say with certainty that the growing economic well-being of the Asian population and demand for entertainment services has recently brought about a significant increase in Asia’s share in the world cinema market.

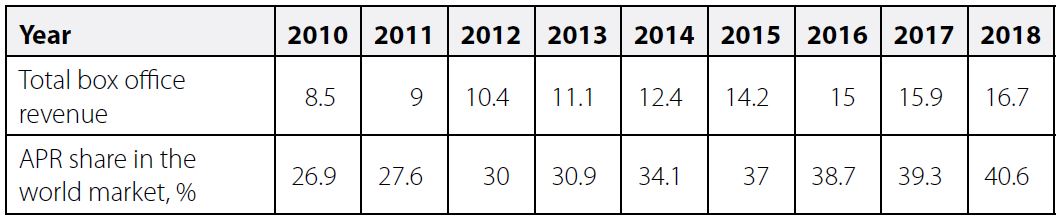

In 2010-2018, total box office revenue in the Asia-Pacific countries approximately doubled to $16.7 billion from $8.5 billion, and the share of the APR countries in the global film market increased significantly to 40.6% from 26.9% (see Table 1). The sharp growth of the Chinese film market was an important factor behind a greater role of the Asian continent on the global scale (at that time it was the second largest in the world after the North American one). In 2019, China’s share was as big as 22% of the world market (MPAA, 2020, pp. 11, 13). It should be noted that four countries—China, Japan, South Korea, and India—account for the bulk of the Asian film market. These countries, which are among the ten largest film markets in the world, generate more than 35% of the world’s box office revenue. It is extremely important that national film makers are very competitive in the markets of these countries: in 2015, national filmmakers in India accounted for 85% of all box office revenue, and in Korea, for 52.2% (UIS Statistics, 2021a). In 2018, in China, national films earned 62% of the total market (Tan, 2019), and in Japan, 54.8% (MPAJ, 2021).

Table 1. Total box office revenue in the Asia-Pacific countries (billion dollars) and the share of the world film market the Asia-Pacific region’s countries accounted for in 2010-2018

Sources: MPAA, 2015; MPAA, 2019.

The size of the domestic market is a key measure of the potential of the national film industry. Positive box office trends mean that the film industry can raise the quality and diversity of its products by improving technological capabilities and attracting talented people, who would otherwise find employment in other sectors of the economy. In addition, large national film markets are important in terms of soft power in that they influence the content of films from other countries, whose producers are interested in getting a firmer foothold on these markets. This is true, above all, of China: according to an expert of the Heritage Foundation, the scripts of Hollywood films are written with a view to promoting the content in the Chinese market (The Heritage Foundation, 2021).

THE DOMESTIC MARKET IS NOT ENOUGH: NOTES ON THE WEST’S LEADERSHIP IN THE FILM INDUSTRY

As we see, Asian countries (largely thanks to the huge Chinese market) account for a significant share of the world cinema market. Moreover, in the Chinese, Japanese, and Indian markets national film producers successfully compete with their foreign counterparts. In foreign markets, however, it is extremely difficult for them to compete with the world’s traditional film giant, the United States, and, to a lesser extent, with some European countries (England, Italy, France). The American, British, and French film industries boast well-established brands that took decades to take shape. The American film industry occupies a special position: thanks to the huge influx of profits from the domestic and foreign markets Hollywood can afford to produce big-budget blockbusters that are almost impossible to compete with in film distribution. In 2019, all top ten box office titles were Hollywood-made (The Numbers, 2021).

It should be borne in mind that the U.S. film industry owes its unique position to control over worldwide film distribution. A. Scott says the American film industry’s main players (“majors”) “directly control distribution systems in all their principal foreign markets, as well as in many more secondary markets” (Scott, 2004, p. 53).

Active actions by the U.S. government have been an important factor in ensuring American film companies’ access to the world markets. Scott mentions one rather telling historical illustration of it: economic aid under the Marshall Plan went hand in hand with a demand that American films would enjoy wider access to national markets (Op.cit., p. 55). Another researcher notes that the alliance between the U.S. government and the American film industry emerged before World War I, and that government subsidies and other support measures played an important role in turning Hollywood into a global “dream factory” (Khan, 2014). A detailed analysis of U.S. government actions that contributed to the global domination of the American film industry is found in a recent article by U. Artamonova (2020).

There are also certain socio-cultural factors that contribute to Western leadership and restrict the export of films from Asian countries with powerful national film industries, such as India. In the academic literature one may come across claims that Bollywood products are “virtually non-exportable” (Lorenzen and Mudambi, 2013, p. 514); however, as I will show below, this viewpoint is losing its relevance. It is widely argued that cultural and linguistic distinctions negatively affect international motion picture trade (see Hanson and Xiang, 2008, pp. 27-28).

The success of strategies for using cultural artifacts as a soft power tool depends on the consumers and their preferences and awareness (Rawnsley, 2012, pp. 129-130). The socio-cultural context of motion picture consumption determines not only the export potential of films, but also their effectiveness in conveying “meanings.” This context was formed under the significant influence of some Western countries’ political will as evidenced by film festivals.

In my previous publication (Paksiutov, 2020), proceeding from P. Bourdieu’s social theory, I attempted to shed light on countries’ film industry-related soft power resources. I concluded that “institutional recognition” in the form of awards and nominations, participation in film festivals, etc. is an important component of soft power in cinematography. In terms of institutional recognition, the global film industry is dominated by the United States and some European countries. By systematically awarding films from Western countries, the “cultural arbiters” legitimize the picture of the world they present and, respectively, the “strategic narratives” of these countries.

The most prestigious European film festivals—the “Big Three” in Cannes, Venice, and Berlin—have had a close relationship with politics since their inception. The oldest film festival in the world, in Venice, was established in 1932 with support from the Italian government (de Valck, 2007, pp. 47-48). The Cannes Film Festival was established in France under a government decision and with direct support from the United States and Britain specifically to counter the cultural influence of fascist Italy (Op.cit., p. 48). The Berlin Film Festival was initiated by a U.S. Army officer and served as “an American instrument in the Cold War” (Op.cit., p. 52). The Western powers’ actions to ensure their dominance in the global film industry proved to be very effective and they still yield political dividends. With the cultural institutions of the United States and European countries remaining dominant, the Asian countries find it difficult to fully compete for leadership in the film industry. This applies, in particular, to China: researchers note that the participation of Chinese films in international film festivals has had “only limited success” in terms of the national soft power strategy (Voci and Hui, 2017, p. 10).

However, digital transformation is likely to bring significant changes to this side of the global film industry. Already now, the importance of film awards as a “high quality mark” for potential viewers is waning, as ever greater audiences watch films using “streaming services,” where the key factor for consumer choice is an automatic recommendation system (Gomez-Uribe and Hunt, 2015). This fact agrees with D. Hesmondhalgh’s statement that in our time “various types of cultural authorities” are losing their importance (Hesmondhalgh, 2018, p. 15).

Current trends will determine the face of a new, Internet-based film industry just as the first half of the last century set the trends and determined the image of the “traditional” film industry of today. Yet the current situation is different in that in addition to Western countries there are now other powers, such as China, that have the resources to participate in creating a new film industry.

DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION OF THE FILM INDUSTRY

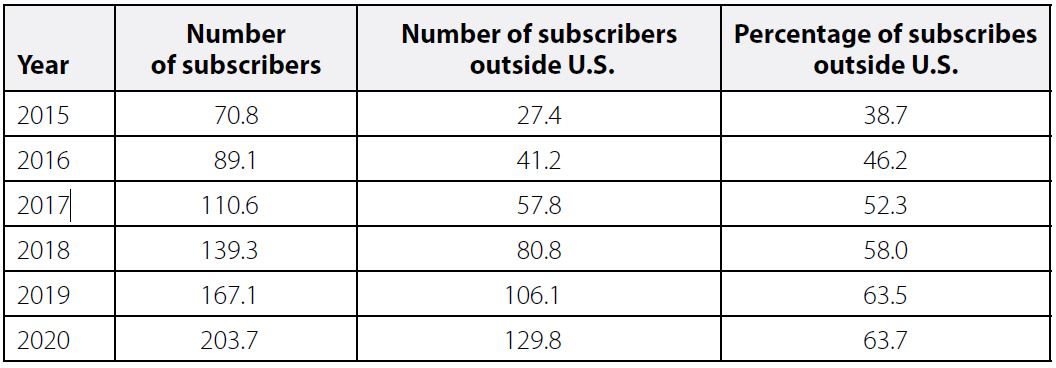

Digital transformation of the film industry has so far attracted relatively little attention from researchers, especially in terms of its importance for Asian countries. Meanwhile, this process undoubtedly has enormous cultural, economic, and political significance. Table 2 below shows the rate at which Netflix, the leading “streaming service,” has been expanding into global markets.

Table 2. Total number of users who paid for Netflix subscription (million), number of users (million), and percentage of subscribers in countries other than the U.S., 2015-2020.

Source: Statista, 2020b; Statista, 2021.

Remarkably enough, it was in 2020, amid the coronavirus crisis, that the Chinese film market for the first time in decades overtook the American one in terms of total box office revenue and became the largest in the world. Notably, this happened when both these markets (as well as the cinema theater markets around the world) experienced a sharp decline: box office revenue in China amounted to $3.09 billion (almost 70% less than in 2019), and the volume of the American market was $2.28 billion (80% less than in 2019) (Yiu, 2021).

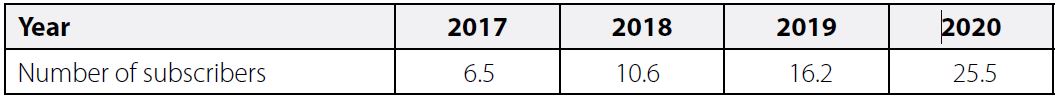

Whereas the COVID-19 pandemic has become the hardest challenge for the theater business, it has proven to be a very favorable factor for “streaming media.” In 2020, the number of Netflix subscribers increased by about 22% (see Table 2). At the same time, in the Asia-Pacific region the expansion of this service proceeded at a rate well above the world average (see Table 3). This achievement looks especially remarkable if one bears in mind that competition in this market has increased significantly over the past few years, especially after the launch of the Disney+ service in 2019.

Table 3. The number of Netflix subscribes in the Asia-Pacific region (million) in 2017-2020

Sources: Statista, 2021; Statista, 2020a.

There are enough reasons to state that in 2020 the digital film market outperformed the movie theater market, with the pandemic merely intensifying the long-term process that had lasted for years.

Although there are popular streaming services in Asian countries—such as Chinese iQIYI and Japanese dTV—they have done little so far to attract foreign subscribers. In January 2020, iQIYI clinched a deal with the Malaysian television operator Astro to enter the Malaysian market, which came as the service’s first-ever step of this kind (Ying, 2020).

FRONTRUNNERS’ PROSPECTS

In light of the current situation in the global film industry and the position of Asian countries in it, let us consider the prospects of four Asian film industry leaders—China, Japan, India, and South Korea—to find out if they will be able to compete with the Western countries for leadership in this sphere in the coming decades.

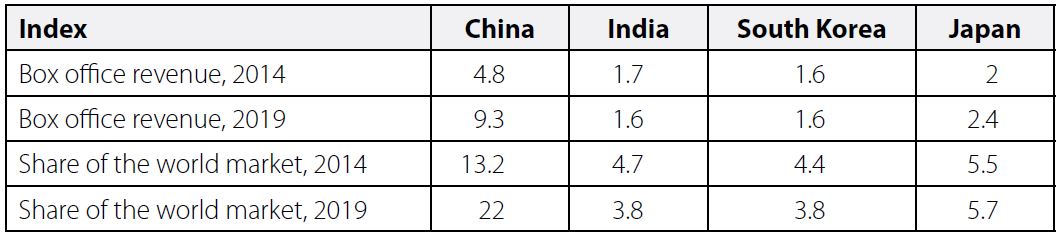

The distinctive Indian film industry has been traditionally considered one of the largest in the world, but in recent years it has faced significant challenges. In 2005-2017, cinema attendance decreased almost by half—to 1.98 billion from 3.77 billion tickets sold per year (UIS Statistics, 2021b). Against this background, India’s share in the world cinema market is decreasing (see Table 4). As is mentioned above, the factor of “cultural distance,” which limits international film trade, has had a significant impact on the Indian film industry: Indian cinema is notable for its unique ethnic flavor, and the country’s population speaks different languages. This situation, however, has some unexpected advantages: the unique nature of the Indian film market protects it from foreign exports (Dastidar and Elliott, 2020), thus ensuring that national filmmakers consistently receive the bulk of the country’s box office revenue.

Table 4. Box office revenue (billion USD) and the share of the national markets in the overall world market (%) in 2014 and 2019 in China, India, South Korea, and Japan

Sources: MPAA, 2015; MPAA, 2020.

India

In the face of declining demand on the domestic market, the main task for the Indian film industry is to increase exports. The Chinese market offers an enormous potential in this regard as the Chinese public shows considerable interest in Indian cinema. In 2017, the Indian films Dangal (directed by Nitesh Tiwari) and Secret Superstar (directed by Advait Chandan) earned $200 million and $118 million in China, respectively—far more than in the domestic market (Vohra, 2018).

As for the digital transformation of the country’s film industry, cooperation with China looks more lucrative for India than a heavy emphasis on U.S. streaming services. In fact, Netflix or Amazon Prime Video find cooperation with the Indian filmmakers attractive, primarily because it can open up opportunities for building up their subscriber base inside India and among the Indian diaspora in other countries, while a joint Sino-Indian service can offer a huge combined market for film industry professionals from both countries. However, political tensions between China and India limit the scope for potentially mutually beneficial cooperation in this area.

Japan and South Korea

In terms of film industry trends that developed in recent years and the digital transformation of cinema, the two countries occupy similar positions. The Japanese film industry in the 21st century is experiencing an upswing: for example, in 2014-2019, the Japanese film market was growing at rates above the world average (see Table 4).

Although the share of South Korea in the global cinema market slightly decreased in 2014-2019 (see Table 4), in the longer term, the national film market demonstrates stable growth: in 2005-2017 cinema attendance in the country grew by more than 50% (UIS Statistics, 2021b). Japanese and South Korean filmmakers have achieved some success on the global scene in recent years. Shoplifters (directed by Hirokazu Koreeda) and Parasite (directed by Bong Joon-ho) received high accolades at film festivals and Academy Awards.

Both countries are involved in quite active cooperation with “streaming media,” which are playing a leading role in shaping a new, Web-based film industry—in particular, with Netflix. In Japan, Netflix invests primarily in animation: the service has long-term partnerships with a number of studios (Woo, 2019). In 2015-2020, Netflix invested about $700 million in the production of Korean films and TV series; in 2021, the service announced that it intends to expand its presence in the country, and for this purpose two of its own production studios will be created in South Korea (Brzeski, 2021). Korean industry professionals’ cooperation with Netflix is in line with the overall strategy for the development of Korean cultural industries, within which global media platforms and social media are actively employed to promote Korean popular culture in world markets (Parc and Kawashima, 2018, p. 29).

It can be assumed that in the coming years, the main trend in the Japanese and Korean film industry will be greater cooperation with streaming services. Japan and Korea will be able to carve a niche for themselves in the U.S.-centric online film industry rather than offer their own alternatives. The placement of Japanese and Korean content on platforms such as Netflix holds little value in terms of national soft power strategies, as it is ultimately the platform owners who determine the content and control its delivery to consumers. Needless to say, these countries’ film strategies will also depend on the general state of their economic and political relations with the United States and China.

China

China is the most likely contender to challenge U.S. leadership in the global film industry in the 21st century. Although in 2020 the Chinese film market became the largest in the world against the backdrop of the coronavirus crisis, it is likely to retain its leading positions in the future. The growing demand from the population, whose disposable incomes, as well as spending on entertainment in general, showed an uptrend was the key factor for the Chinese market growth. While in 2005 Chinese cinema theaters sold 157.2 million tickets, in 2017 ticket sales were already up to above 1.62 billion (UIS Statistics, 2021b). In contrast to the oversaturated U.S. domestic market, the Chinese one still has a big potential for growth.

It is far more difficult to challenge the United States as the world’s leading exporter of motion pictures. At a time when the success of the American film industry is determined not only by the preferences of consumers around the world, but also by its control over the global distribution and marketing of films, China’s focus is on co-production and investment in American film companies. According to A. Kokas, the main motive behind the production of Sino-U.S. films (for instance, The Great Wall, Kung Fu Panda) is Hollywood companies’ wish to penetrate the Chinese market schielded by government protectionist measures, on the one hand, and China’s “pursuit of global cultural power,” on the other (Kokas, 2017, p. 65). Thanks to the huge volume of the domestic market, Chinese film companies can independently produce big-budget blockbusters for promotion abroad. Booming markets in the Asia-Pacific region offer the greatest opportunities for Chinese cinema. In this regard, the main tasks are creating a distribution system and infrastructure for film screening (which can be implemented, for example, in conjunction with the One Belt One Road project) and marketing activities.

Tsvetkova shows in her article that China is the United States’ main competitor for leadership in the global digital economy as borne out by such indicators as the total volume of this sector and presence on the list of the world’s 15 largest Internet companies (Tsvetkova, 2018). Building upon this potential, China can successfully market its digital products abroad. The global success of the TikTok application proves this quite vividly.

Speaking about cinema as an instrument of China’s foreign policy influence and a means of communicating the national narrative to the world, it is necessary to remember that the Chinese soft power strategy implies projection of a certain set of values that constitute an alternative to those of the West (Fliegel and Kříž, 2020, p. 8). As one scholar has put it bluntly, the difference between China’s ideology and “the West’s political values” limits the effectiveness of the cultural sources of Chinese soft power (Yang, 2016, p. 86). However, the values of the modern West, and of the Western cultural elites in particular, can hardly be called universal. Film industry professionals in China (and other states that seek to compete with the United States and European countries in the global cultural space) can be advised to put emphasis on depicting values that are shared by people of different civilizational identities, for example, family values.

Finally, Chinese cinema is currently lagging significantly behind Western countries in terms of recognition by international cultural institutions, which is a major component of cultural influence. It is an imperative for China not only to obtain awards at U.S. and European ceremonies, but to create and promote its own film festivals and awards. From this point of view, certain successes have already been achieved. For example, the Hong Kong-based Asian Film Awards tends to favor Chinese films (Frater, 2016). The Shanghai International Film Festival is the first “competitive” Chinese film festival to have been accredited by the International Federation of Film Producers’ Associations (there were 15 such festivals around the world in 2020) (FIAPF, 2021). Only time will tell if these institutions can gain credibility and wide acclaim in the eyes of the public not only in Asia, but also in other continents; and this depends, among other things, on the quality of the Chinese artists’ creative endeavor.

* * *

The film industry is an industry of significant economic and political importance, in which the economic, political, and cultural interests of various agents (from individual personalities, actors and spectators to countries and supranational associations) are intricately intertwined. Digital transformation is changing the logic of industry development literally before our eyes; understanding what the film industry will be like in the 21st century (and whether it will continue to exist in its traditional form at all) requires intensive research. In this article, we set the task of contributing to the study of the modern film industry and describing the situation in and prospects for Asian countries. Methodologically, we were guided by the understanding of cultural industries as industries that produce “meaning” and whose success on the global arena is determined by the condition of the internal market, government policies and opportunities for the perception of the “meaning” of their products by foreign audiences (which is facilitated by the recognition from international cultural institutions).

This study brings us to the following conclusions:

- The Asia-Pacific region’s film markets had been growing at a high rate prior to the onset of the coronavirus crisis, primarily thanks to China. The markets of China, Japan, South Korea, and India collectively accounted for more than 35% of global box office revenue in 2019. At the same time, a number of factors, including control over the cinema distribution system, currently sustain the almost unchallengeable leadership of the United States as a film exporter.

- Cultural institutions (award ceremonies, film festivals) give Western countries a competitive advantage; the leading world institutions (Oscar, Cannes and Venice film festivals, etc.) located in the United States and Europe were created with the direct participation of the authorities of countries that sought to increase their cultural influence in the international arena.

- Streaming services (Netflix, etc.) are becoming increasingly important for the global film industry; this process has been greatly accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to be culturally competitive, Asian countries must offer their alternatives to Western services.

- The only country that has the resources to fully compete with the United States for leadership in the field of cinema is China (thanks to the scale of the national film distribution and the powerful sector of the digital economy). Film industry development prospects in India, Japan, and South Korea will largely be determined by their interaction with partners in the United States and China.

Naturally, the problem under consideration requires to be analyzed and studied further. Here we could merely outline the main trends, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic clearly has demonstrated that unpredictable factors can have a huge impact on the development of culture-related industries, filmmaking included.

Anaz, N. and Ozcan, C. C., 2016. Geography of Turkish Soap Operas: Tourism, Soft Power, and Alternative Narratives. In: Egresi, I. (ed.). Alternative Tourism in Turkey. Cham: Springer.

Artamonova U. Z., 2020. Amerikansky kinematograf kak instrument publichnoi diplomatii SShA [American Cinematography as an Instrument of the U.S. Public Diplomacy]. Analiz i prognoz. [Analysis and Forecasting. IMEMO Journal], No. 2, pp. 110-122.

Asian Development Bank, 2011. Asia 2050: Realizing the Asian Century. Singapore: Asian Development Bank.

Brzeski, P., 2021. Netflix Expands South Korean Footprint, Leasing Two Production Facilities. Hollywood Reporter, 6 January [online]. Available at: <www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/netflix-expands-south-korean-footprint-leasing-two-production-facilities> [Accessed 21 January 2021].

Dastidar, S. G. and Elliott, C., 2020. The Indian Film Industry in a Changing International Market. Journal of Cultural Economics, 44(1), pp. 97-116.

de Valck, M., 2007. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

FIAPF, 2021. Competitive Feature Film Festivals. FIAPF [online]. Available at: <www.fiapf.org/intfilmfestivals_sites.asp> [Accessed 12 March 2021].

Fliegel, M. and Kříž, Z., 2020. Beijing-Style Soft Power: A Different Conceptualization to the American Coinage. China Report, 56(1), pp. 1-18.

Frater, P., 2016. Asian Film Awards Honor Best of the Region’s Filmmaking. Variety, 11 March [online]. Available at: <variety.com/2016/film/spotlight/asian-film-awards-honor-best-of-the-regions-filmmaking-1201728145/> [Accessed 24 March 2021].

Gomez-Uribe, C. A. and Hunt, N., 2015. The Netflix Recommender System: Algorithms, Business Value, and Innovation. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (TMIS), 6(4), pp. 1-19.

Hall, I. and Smith, F., 2013. The Struggle for Soft Power in Asia: Public Diplomacy and Regional Competition. Asian Security, 9(1), pp. 1-18.

Hanson, G. H. and Xiang C., 2008. Testing the Melitz Model of Trade: An Application to U.S. Motion Picture Exports. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hesmondhalgh, D., 2018. Kulturnye industrii [Cultural Industries]. Moscow: HSE Publishing House.

Khan, S. A., 2014. Hollywood and the State: A Longtime Partnership. Mises Institute, 1 August [online]. Available at: <mises.org/library/hollywood-and-state-longtime-partnership> [Accessed 21 January 2021].

Kokas, A., 2017. Hollywood Made in China. Oakland: University of California Press.

Lorenzen, M. and Mudambi, R., 2013. Clusters, Connectivity and Catch-Up: Bollywood and Bangalore in the Global Economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 13(3), pp. 501-534.

MPAA, 2019. 2018 THEME Report. MPAA, 21 March [online]. Available at: <www.motionpictures.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/MPAA-THEME-Report-2018.pdf> [Accessed 11 January 2021].

MPAA, 2020. 2019 THEME Report. MPAA, 11 March [online]. Available at: <www.motionpictures.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/MPA-THEME-2019.pdf> [Accessed 11 January 2021].

MPAA, 2015. Theatrical Market Statistics 2014. MPAA, 11 March [online]. Available at: <www.motionpictures.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MPAA-Theatrical-Market-Statistics-2014.pdf> [Accessed 11 January 2021].

MPAJ, 2021. Statistics of Film Industry in Japan. MPAJ [online]. Available at: <eiren.org/statistics_e/index.html> [Accessed: 11 January 2021].

Negus, K., 1999. The Music Business and Rap: Between the Street and the Executive Suite. Cultural Studies, 13(3), pp. 488-508.

Nye, J. S., 1990. Soft Power. Foreign policy, 80, pp. 153-171.

Nye, J. S., 2014. The Information Revolution and Soft Power. Current History, 113(759), pp. 19-22.

Paksiutov, G. D., 2020. “Myagkaya sila” i “kulturny kapital” natsii: primer kinoindustrii [“Soft Power” and “Cultural Capital” of Nations: The Case of Film Industry]. Mirovaya ekonomika i mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya [World Economy and International Relations], 64(11), pp. 106-113.

Parc, J. and Kawashima, N., 2018. Wrestling with or Embracing Digitalization in the Music Industry: The Contrasting Business Strategies of J-Pop and K-Pop. Kritika Kultura, 30, pp. 23-48.

Purushothaman, U., 2010. Shifting Perceptions of Power: Soft Power and India’s Foreign Policy. Journal of Peace Studies, 17(2&3), pp. 1-16.

Rawnsley, G., 2012. Approaches to Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Taiwan. Journal of International Communication, 18(2), pp. 121-135.

Roselle, L., Miskimmon, A. and O’loughlin, B., 2014. Strategic Narrative: A New Means to Understand Soft Power. Media, War & Conflict, 7(1), pp. 70-84.

Saberi, D., Paris, C. M. and Marochi, B., 2018. Soft Power and Place Branding in the United Arab Emirates: Examples of the Tourism and Film Industries. International Journal of Diplomacy and Economy, 4(1), 44-58.

Scott, A., 2004. Hollywood and the World: The Geography of Motion-Picture Distribution and Marketing. Review of International Political Economy, 11(1), pp. 33-61.

Statista, 2020a. APAC: Number of Netflix Memberships 2017-2019. Statista, 19 May [online]. Available at: <www.statista.com/statistics/1118182/apac-number-of-netflix-memberships/> [Accessed 21 January 2021].

Statista, 2020b. Netflix’s International Expansion. Statista, 24 January [online]. Available at: <www.statista.com/chart/10311/netflix-subscriptions-usa-international/> [Accessed 21 January 2021].

Statista, 2021. Netflix’s Paid Subscribers Count by Region 2020. Statista, 3 February [online]. Available at: <www.statista.com/statistics/483112/netflix-subscribers/> [Accessed 15 February 2021].

Su, W, 2010. New Strategies of China’s Film Industry as Soft Power. Global Media and Communication, 6(3), pp. 317-322.

Tan, J., 2019. Another Record Year for China’s Box Office, But Growth Slows. Caixin Global, 2 January [online]. Available at: <www.caixinglobal.com/2019-01-02/another-record-year-for-chinas-box-office-101365697.html> [Accessed 11 January 2021].

The Heritage Foundation, 2021. How China Is Taking Control of Hollywood. The Heritage Foundation [online]. Available at: <www.heritage.org/asia/heritage-explains/how-china-taking-control-hollywood> [Accessed 20 March 2021].

The Numbers, 2021. Top 2019 Movies at the Worldwide Box Office. The Numbers [online]. Available at: <www.the-numbers.com/box-office-records/worldwide/all-movies/cumulative/released-in-2019> [Accessed 24 March 2021].

Thussu, D. K., 2016. The Soft Power of Popular Cinema—the Case of India. Journal of Political Power, 9(3), pp. 415-429.

Tsvetkova, N. N., 2018. Tsifrovye tehnologii v stranah Azii i Afriki [Digital Technologies in Asian and African Countries]. Aziya i Afrika segodnya [Asia and Africa Today], 9, pp. 25-32.

UIS Statistics, 2021a. Percentage of GBO of All Films Feature Exhibited That Are National. UIS Statistics [online]. Available at: < http://data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=59 > [Accessed 11 January 2021].

UIS Statistics, 2021b. Total number of admissions of all feature films exhibited. UIS Statistics [online]. Available at: <data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=CUL_DS> [Accessed 17 January 2021].

Vlassis, A., 2016. Soft Power, Global Governance of Cultural Industries and Rising Powers: The Case of China. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 22(4), pp. 481-496.

Voci, P. and Hui, L. (eds.), 2017. Screening China’s Soft Power. Abingdon: Routledge.

Vohra, P., 2018. Indian Movies Attract Millions around the World. CNBC, 2 August [online]. Available at: <www.cnbc.com/2018/08/03/indian-films-attract-millions-globally-and-it-appears-to-be-growing.html> [Accessed 21 January 2021].

von Mises, L., 1963. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. San Francisco: Fox & Wilkes.

Wang, S. L. et al., 2020. Cultural Industries in International Business Research: Progress and Prospect. Journal of International Business Studies, 51, pp. 665-692.

Woo, G., 2019. Netflix Announces Plans for Many New Original Anime Series. Screen Rant, 12 March [online]. Available at: <screenrant.com/netflix-original-anime-series-future/> [Accessed 21 January 2021].

Yang, Y., 2016. Film policy, the Chinese Government and Soft Power. New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film, 14(1), pp. 71-91.

Ying, W., 2020. Chinese Video Streaming Site iQIYI Makes First Overseas Move. Nikkei Asia, January 7 [online]. Available at: <asia.nikkei.com/Business/Startups/Chinese-video-streaming-site-iQiyi-makes-first-overseas-move> [Accessed 20.03.2021].

Yiu, E., 2021. China’s Box Office Expands to the World’s Largest. South China Morning Post, 1 January [online]. Available at: <www.scmp.com/business/companies/article/3116128/chinas-box-office-expands-worlds-largest-defying-year-disastrous> [Accessed 21 January 2021].