The Russian Far East is a strategically important region due to its favorable geographical location and rich natural resources. However, several factors make this region vulnerable, one of them being migration processes which have a serious impact on the local social and political situation. In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the region experienced a high inflow of migrants from Central Asia and the South Caucasus, whose ethno-cultural and religious traditions are in stark contrast to the local way of life. Migrants have built Islamic infrastructure and the halal industry in the region, and more and more often they ask for plots of land to build mosques there, occasionally provoking conflicts with local residents. There are also problems caused by the growth of Islamic extremism. In August 2015, Russian Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev told the media about attempts by Islamic State (ISIS) emissaries to recruit migrant workers living in the Russian Far East. Some local residents have also gone to the Middle East to join ISIS forces. “Foreign citizens, who may be involved in international terrorist and extremist organizations and illegal armed groups, are now trying to become legalized in taiga villages and major cities of the Russian Far East,” Patrushev said.

Demographic Processes in the Muslim Community in the Russian Far East

The Muslim community in Russia’s Far Eastern Federal District includes 33 officially registered Muslim organizations affiliated with various federal organizations, above all the Central Spiritual Muslim Board of Russia and the Spiritual Muslim Board of the Asiatic Part of Russia, which have been competing with each other for a decade. There are also fully independent communities. The majority of Muslim organizations have multi-ethnic memberships (for example, many communities are chaired by people from Central Asia, while their imams are from the North Caucasus).

At the end of the 19th century, the Muslim community in the Russian Far East included mostly internal migrants from the Middle and Lower Volga regions and the Urals, mainly Tatars and Bashkirs. Later, the migration policy of the Soviet government (repression, labor recruitment, and relocation of workers to sites of major construction projects) significantly changed the ethnic composition of the Muslim population in the Russian Far East: in 1989, there were 104,697 members of ethnic groups from the Volga region (Tatars and Bashkirs), 30,696 people from Central Asia, 14,547 people from the North Caucasus, 19,374 Azerbaijanis, and 647 people of other ethnic groups.

In 1989-2010, the Tatar and Bashkir population of the Far Eastern Federal District decreased by 55 percent from 104,697 to 46,799 people. The reason was not only the natural decline and intensive assimilation but also the resettlement of a large number of Muslims to other Russian regions due to the economic difficulties of the 1990s-2000s. According to censuses, the population of the Russian Far East decreased from 7,950,005 to 6,293,129 people between 1989 and 2010. Since the late 1990s, more than 1,830,000 people have left the region, whose population shrank by 22.7 percent in the period from 1991 to 2013.

Even a 40-percent increase in the number of migrants from Central Asia has not compensated for the general decrease in the number of Muslims, specifically Azerbaijanis and North Caucasians. Over the last 21 years, the Muslim population of the region has declined by 29 percent from 169,961 to 119,889 people. At the same time, the inflow of migrants from Central Asia has changed the composition of the local Muslim community.

For example, the population of the Primorsky Territory is less than two million, but, according to the head of the local department of Russia’s Federal Migration Service, Maxim Beloborodov, more than 116,000 migrants were registered in the region in the first half of 2014 alone. Migrants make up five percent of the local population, and as many stay in the region illegally. “According to statistics, we accommodate 24,000 Uzbeks and 19,000 Chinese every year,” Beloborodov said. “The Chinese work for some time here and then go home. The situation with migrants from Central Asia is different: they do their best to stay here permanently.”

The local population’s attitudes to migrants moving to the region for permanent residence differ according to their ethnic origins. Ethnic groups that are particularly undesirable to locals are Chechens and Dagestanis (they are not welcome to 62.7 percent of respondents), as well as Armenians, Azerbaijanis and Georgians (51.9 percent).

Young people are also opposed to giving permanent residence to migrants from Central Asia—Tajiks and Kyrgyz (50.9 percent)—and China (52.2 percent). The attitude is particularly negative in places with a high percentage of migrant workers. There one can often hear phrases like “We are afraid;” “Why have they come?” or “I hate …” Ethnic negativism is directed not only against migrants but also against members of ethnic groups who settled in the region long ago. The result is permanent tensions between migrants and the local population.

Ethno-Cultural and Territorial Factors of Islamic Renaissance

Historian and ethnologist Galina Yermak of Vladivostok says that Muslims “tend to group according to their region of origin: the Volga region: Tatars and Bashkirs; the Caucasus: Chechens, Avars, Azerbaijanis, Dargins, Kumyks, and Ingush; and Central Asia: Uzbeks and Tajiks. The issue of leadership among these groups is rather ambiguous. For example, Tatars, who settled in the Primorsky Territory long ago, head local Muslim religious organizations. At the same time, Uzbeks are more active mosque-goers. People from the North Caucasus are more religious than Tatars and Azerbaijanis. If migrant flows from Central Asia do not subside, the Islamic factor will play a growing role in social relations in the region.”

Tatars are not prominent in the religious life of Muslims in the Russian Far East, and they do not go to mosques often. According to the chairman of the religious Muslim organization of the city of Blagoveshchensk, Abdimukhtar Palvanov, the majority of 300 to 350 Muslims who attend Friday prayers are Uzbeks, Tajiks and people from the North Caucasus. Therefore it is not surprising that it was North Caucasians and Central Asians who started the process of Islamic renaissance in some areas of the Far Eastern Federal District. For example, Alimkhan Magrupov from Uzbekistan became the first imam of Vladivostok and later the first mufti of the Primorsky Territory. In 1993, he registered the Vladivostok Municipal Muslim Religious Organization Islam, the first Islamic organization in the Russian Far East, and became its head. The house of prayer which he established became the center of religious life for local Muslims. In 1998, Islam and other Muslim organizations of the region founded the first muftiate in the Russian Far East, called Islam, which was also headed by Magrupov. In 1998, Islam joined the Spiritual Muslim Board of the Asiatic Part of Russia, and in February 1999, at the 2nd forum of Muslims of Asiatic Russia, Magrupov received a firman (decree) appointing him qazi (religious adjudicator) of the Primorsky Territory. In 2001, he was replaced as the head of the regional ummah by Damir (Abdallah) Ishmukhamedov, a Tatar who was born and grew up in Uzbekistan. In 2000-2013, he was the leader of regional Muslims, chairman of the Qaziyat Muslim Board of the Primorsky Territory, and mufti of the Far Eastern region representing the Spiritual Muslim Board of the Asiatic Part of Russia. He has been replaced by Ingush Rukman Kartoyev, who in 2013 was also elected chairman of the Spiritual Muslim Board of the Primorsky Territory, which has not been officially registered yet.

The situation developed similarly in other regions of the Russian Far East. Former military officer Ismail Usmandzhanov from Uzbekistan became the head of the first post-Soviet Muslim community in the Amur Region. Abdimukhtar Palvanov, an ethnic Uzbek from Kyrgyzstan’s Osh Region, is now chairman of the Muslim community of Blagoveshchensk, which is affiliated with the Central Spiritual Muslim Board of Russia. Tajik Saidrahmon Rasulov is imam khatib of the Mahallia Ahli Tarikat organization in the Jewish Autonomous Region. North Caucasians play a decisive role in the Muslim community in Kamchatka. In 1998-1999, when the Spiritual Muslim Board of the Asiatic Part of Russia was established, it was joined by the Muslim organization of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, headed by Usman Usmanov from Dagestan. Later, he was replaced by Alani Dabuyev from Chechnya. In 2010, Bashir Bashirov from Dagestan was named the head of the Religious Association of Muslims of the Kamchatka Region. Abdulkasym Abdulloyev from Tajikistan heads Nur, one of the most active Muslim organizations in the Russian Far East. People from Dagestan were the first and second imams of a local mosque.

Tatars head Muslim communities in the Sakhalin, Magadan and Khabarovsk regions and the Primorsky Territory. The Muslim community in Magadan was established in the mid-1990s and is based on the Altyn Ay (Golden Moon) Tatar-Bashkir public organization. It is no wonder that ethnic Tatar Rafael Fatykhov, a businessman and member of the Magadan City Council, heads both Altyn Ay and the Congregation of the Magadan Mosque organization, which is in the jurisdiction of the Central Spiritual Administration of Muslims. At the same time, the Muslim community of Susuman, Magadan Region, was organized by Ingushes, who have been working at local gold mines since Soviet times.

There are also two Muslim communities in Sakhalin. One, mainly Tatar, community was formed around the Musulmanin regional public fund and the Makhallia community, affiliated with the Central Spiritual Muslim Board of Russia. The other, international one is the Sakhalin Muslim community, which is a member of the Spiritual Muslim Board of the Asiatic Part of Russia. Its mosque is attended by people from the Caucasus and Central Asia, Tatars, Russians, Koreans, and Buryats. Maxim Surovtsev, an ethnic Russian who converted to Islam, was the first chairman of the community. In 2011, he was replaced by Chechen Rasul Khaduyev. Abdumalik Mirzoyev from Tajikistan is the imam of the community. The Muslim community in Khabarovsk has always been headed by Tatars: Raul Safiullin, Rafil Khairutdinov, Hamza Kuznetsov, Aydar Garipov, and Ahmad Garifullin. In the Primorsky Territory, Tatars head Muslim communities in Nakhodka, Artyom, and Ussuriysk, but Tajiks who served as chairmen of communities or imams have more influence there.

The multi-ethnic composition of the leadership of Muslim communities in the Russian Far East does not have much impact on inter-ethnic relations within Muslim diasporas. Since Muslims make up a significant minority in the Far Eastern Federal District, their common problems make them work together to solve them, while their relations with the authorities depend on the positions of their leaders and their ability to carry on dialogue with municipal and regional officials.

The Construction of Mosques in the Russian Far East

The problem of building new mosques and restoring old ones is part of this dialogue across Russia. There are about 7,000 mosques in the country. New mosques are built primarily in the North Caucasus and Tatarstan. In the majority of non-Muslim regions, the construction of new mosques irritates the local population, and the local authorities have to take this into account. Even in Moscow, a proposal of the Russian Council of Muftis to build small mosques in various neighborhoods of the city where Muslims live was not supported by the municipal authorities. Against this background, the situation in the Russian Far East looks much better.

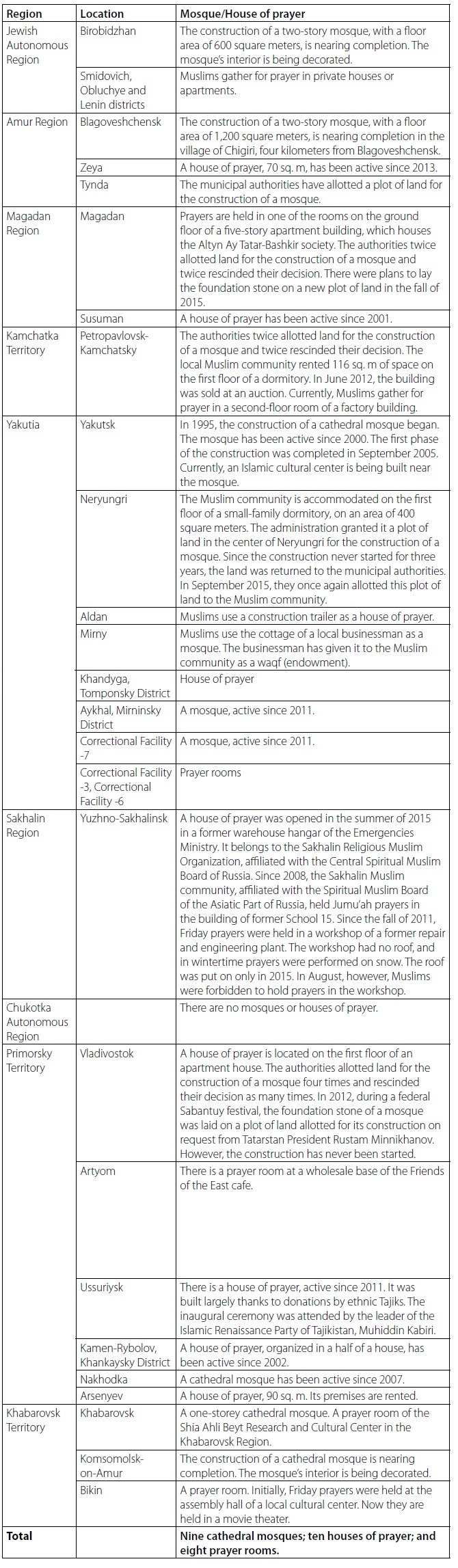

Mosques and Muslim Houses of Prayer in the Russian Far East in 2015

Note. This table uses data from the websites of Islam and Society (http://www.islamio.ru) and the Spiritual Muslim Board of the Russian Federation (http://www.dumrf.ru), as well as information provided by the Administration of the Khabarovsk Territory and former mufti of the Qaziyat Muslim Board of the Maritime Territory Damir Ishmukhamedov, and field data collected by Alexei Starostin (2014-2015).

The most acute situation is in Vladivostok where the number of Muslims is constantly growing, but the city still has no mosque. Plans to build a mosque began to be discussed in 1998, but it was only in 2012 that an appropriate plot of land was allotted for the construction. During a federal Sabantuy (a Tatar festival held annually in various Russian cities), Tatarstan President Rustam Minnikhanov and Chief Mufti of the Central Spiritual Muslim Board of Russia Talgat Tadzhuddin laid the foundation stone of a mosque named after Tatarstan’s capital Kazan. However, the construction was never started for bureaucratic reasons (several competing Muslim organizations laid claims to the land).

The allocation of land for the construction of a mosque in Khabarovsk has also taken too long. Sarverdin Tuktarov of the Khabar municipal Tatar ethnic and cultural autonomous community in Khabarovsk has said that there are no mosques in the city. There is a house of prayer, but officially it is not registered as a mosque. In the late 2000s, Muslims asked the regional authorities for a plot of land to build a mosque. The regional government offered 18 different plots of land. Finally, community members chose an appropriate plot, but they procrastinated going through registration formalities and the plot of land was given to another organization.

From November 2013 to April 2014, the regional government received seven requests from Muslims. In January 2014, they met with a deputy chairman of the regional government in charge of regional policies, Victor Martsenko, after which the municipal administration was asked to prepare additional proposals regarding the allocation of land for building a mosque in Khabarovsk. The authorities finally proposed a plot of land to the Muslim community, but the allocation of land was again postponed due to a change in the community’s leadership.

Meanwhile, the foundations of five new mosques have been laid in the Khabarovsk region. When the parties are ready for dialogue, the lack of mutual understanding can be resolved. In addition, the construction of new mosques does not irritate the local population.

Islamic Radicalism

There are several radical organizations active in the Far Eastern Federal District, which include migrants and local ethnic Tatars. Two of these organizations are banned in Russia; they are the Islamic Party of Turkestan (formerly known as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan) and Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami.

The case of a gang of Islamists from the Islamic Party of Turkestan, who were active in Vladivostok in 2008-2011, caused a wide public response. The gang leader, Anvardzhan Gulyamov from Uzbekistan, had the typical fate of a migrant: he came to the capital of the Primorsky Territory in 1993 and worked in trade and construction. Before immigrating to Russia, he underwent training in the Fergana Valley by Abduvali-qori Mirzoyev, one of the ideologists of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU). Being well-versed in religion, he established contact with an informal leader of the Uzbek diaspora in the Primorsky Territory, Halimjon Nurmatov, and received the status of “spiritual guide” of the Uzbek diaspora. Gulyamov acquired a fake Afghan War veteran’s certificate which helped him receive a four-room apartment in Vladivostok and build a private house, where he organized a “Muslim dormitory” and where Uzbek migrants were legalized.

In 2005, Gulyamov briefly returned to Uzbekistan, where he bought passports for at least five members of Khanabad Jamaat, a radical group accused of extremist activity in Uzbekistan. Shortly after that, he took them in his car out of the Andijan Region. Four years later, in May 2009, there was an armed clash in the region between government forces and a group of unidentified men, followed by a series of nationwide high-profile assassinations and assassination attempts. After the group returned to Vladivostok, they laid the groundwork for a new Jamaat which was to become the basis of a Salafi underground organization in the Primorsky Territory.

Initially, the Uzbek radicals had little influence among Vladivostok Muslims. However, in 2007, Gulyamov and Nurmatov invited the imam of a local house of prayer, Abdulvohid Abdulhamitov, to join their Jamaat. The organization was also joined by a group of parishioners, largely Chechens and Ingushes from the North Caucasus. The move made the recruitment of new members much easier. Simultaneously, Gulyamov maintained contact with similar organizations in Saudi Arabia, Egypt and other Arab countries. He helped several Jamaat members go to the Afghan-Pakistani border where they took part in hostilities. Some members moved to Syria and Egypt.

In 2008 and 2009, twelve activists of the Primorsky Territory Jamaat, including imam Abdulhamitov, were arrested. Several members of the group escaped but were arrested later in other regions of Russia. Some of them were extradited to Uzbekistan where they were sentenced to long prison terms. On March 14, 2009, three members of the group were killed in a police operation in Vladivostok. The Interfax news agency reported that “a large amount of radical Islamist literature and videotapes were found in an apartment where the bandits had been living. Police also seized a large number of armaments and ammunition brought from Chechnya.”

Gulyamov went into hiding, but a year later he resumed the recruitment of new members. His fellow Uzbeks selected candidates from among members of the Uzbek diaspora, indoctrinated them, helped them resolve ID issues, and accommodated new Jamaat members in a “Muslim dormitory.”

In 2011, Primorsky Territory police, in close cooperation with the security services of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, carried out an operation to neutralize the remaining members of the group. They arrested three persons closely associated with Gulyamov and deported them to Uzbekistan. In all, local police arrested more than 30 criminals, most of whom were deported to Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

Islamic radicals from the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan are also active in Ussuriysk. In the late 2000s, local FSB (Federal Security Service) officers detained a citizen of Kyrgyzstan who was on the international wanted list and who was suspected of recruiting migrants from Central Asia and sending them to Taliban training camps in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In addition, he was the organizer of new IMU cells. In September 2013, the Khabarovsk Regional Court found Tajik citizens Mahmadsoleh Makhanov, Abdukarim Sattorov and Alisher Davlatov guilty of participating in the activities of the terrorist Islamic Party of Turkestan. They came to Khabarovsk in March 2013, settled in a suburban village and began to persuade local Muslims to join the Islamic Party of Turkestan (IPT).

Security forces noted the presence of Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami (HTI) on the Sakhalin Island, too. In 2013, FSB and Interior Ministry officers detained a former military man, Gatraza Gabeyev, who in 2012-2013 recruited five residents of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk into HTI. At meetings with the recruits, Gabeyev propagated the establishment of a caliphate and justified terrorist acts in the North Caucasus. In Gabeyev’s apartment, police found sixteen 9 mm live rounds, two F-1 antipersonnel defensive grenades and two fuses for them, and an identity card of an officer of the Federal Law Enforcement Agency/Antiterrorist Center, which was very similar to an FSB identity card.

In 2015, activists from Islamic State, which is banned in Russia by court, were reported to have appeared in the Russian Far East. The head of Sodruzhestvo, a Muslim public movement in the Khabarovsk, Khamza Kuznetsov, said that “recruiters target primarily unemployed migrants and offer them 50,000 rubles a month for joining ISIS.” “Propaganda videos are distributed via social media to present an attractive image of ISIS among the Muslim youth,” Kuznetsov said. “Tens of thousands of Muslims can view these videos, as almost everyone has a smartphone or tablet nowadays. More and more radical ideas are disseminated via social media. These ideas, coupled with the economic crisis and the tightening of immigration legislation, can cause young people to join the militants for money.”

Subsequent events confirmed these words. On October 22, the FSB Sakhalin Department reported that a local resident had left to join ISIS. This was not a young hothead but a middle-aged mature man. He had come to the island five years earlier and worked as a welder. He was a good specialist but was overly religious. According to the ASTV.ru website, he always attended Friday prayers held in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk by the Sakhalin Muslim community, affiliated with the Spiritual Muslim Board of the Asiatic Part of Russia.

Efforts to counter Islamic radicalism in the Russian Far East do not have any local specifics, but, since there have been no extremist or terrorist acts in the region, local security agencies attach great importance to preventive measures. The authorities try to avoid conflicts with Muslims, as evidenced, for example, by their consent to the opening of new mosques.

Methods used to fight extremism in the Russian Far East, like in other regions of Russia, include a ban on various kinds of religious literature. There is a shortage of books on Islam in the region. In a bid to solve this problem, the Qaziyat Muslim Board of the Primorsky Territory from 2001 to 2013 published in Vladivostok over 10,000 copies of the booklets The Pillars of Iman, Islam and Prayer, This Is Haram—Major Sins in Islam, Muslim Aqidah in Questions and Answers, Zakat and Fasting in Ramadan, Umrah and Hajj, and others. However, all these publications were soon included in the federal list of extremist literature.

On April 30, 2013, literature from this list was found in the reading room at a mosque of the Islam organization in Nakhodka. In January 2015, the Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk Municipal Court ruled that the book I Am a Muslim. The First Russian Edition, seized from detainees held in the city’s detention center, was extremist. In August 2015, the Central District Court of Komsomolsk-on-Amur began proceedings on an administrative case against the Nur organization and the mosque’s imam Magomedrasul Gimbatov. They were accused of distributing extremist literature and keeping it in the mosque. One of the organization’s founders, Bakhtiyar Yarmanov, said that “very many believers come to the mosque, and we cannot control what literature they may bring. These books do not belong to either the imam or the community.”

Today, the list of extremist literature includes over 2,000 books on Islam. However, the Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk Municipal Court’s decision to ban the booklet Prayer to God: Its Meaning and Place in Islam, published by the Spiritual Muslim Board of the Asiatic Part of Russia in Moscow in 2009, caused a national scandal. On August 12, 2015, the court ruled that the booklet, which contained quotes from the Quran, was extremist. Chechnya’s leader Ramzan Kadyrov described the court ruling as outrageous, aimed at undermining stability in Russia, extremist and provocative. On Kadyrov’s instructions, an appeal was filed with the Judicial Chamber for Civil Cases of the Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk Regional Court, demanding that the ruling be reversed as unlawful and unfounded. Kadyrov demanded “severe punishment for the instigators who handed down this ruling and who try to blow up the situation in our country.”

The Russian Prosecutor General’s Office denounced the Chechen leader’s statement and emphasized that legal issues should be resolved in the legal framework and that no one should make sharp statements. Kadyrov responded immediately: “I called the judge and the prosecutor who recognized the Quran as ‘extremist’ devils and instigators. Their ruling has no relation to their professional activity. Instead of protecting the law and interests of Russia, they make stupid decisions which undermine the foundations of stability and security. Moreover, they publicly insulted millions of Russians and 1.5 billion Muslims around the world.”

Kadyrov’s statements caused the State Duma to join in the discussion. Parliament deputies unanimously denounced the court ruling, which evoked excuses from the chairman of the Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk court, Alexander Chukhrai: “The Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk prosecutor’s office has already appealed the municipal court’s decision declaring the book Prayer to God extremist. The prosecutor’s office has explained that they asked the court to recognize as extremist only the views of the book’s author, not verses from the Quran. The prosecutor’s office believes that the judge made the wrong decision.”

The scandal resulted in a bill introduced by President Putin to the State Duma on October 14, 2015, prohibiting the canonical texts of the Bible, Quran, Tanakh, and Kanjur and quotations from them from being designated extremist. The bill was passed as a federal law on November 23, 2015. Another bill introduced to the parliament proposed denying courts below the level of a regional court the right to give rulings recognizing religious texts as extremist.

* * *

The processes taking place in the Muslim community in the Russian Far East are part of changes in Russia’s ummah. Religious radicalism is growing. Hizb ut-Tahrir and the IMU (IPT) obviously seek to strengthen their positions in the region. In 2015, Islamic State emissaries appeared there to try to recruit local Muslims, especially migrants. Local Islamists maintain ties with radicals from Central Asia.

The activity of Muslims in the Russian Far East and demographic changes in the region reflect the eastward and northward advance of Islam in Russia—in the Urals and Siberia. Despite its geographical remoteness from conflicts involving radical Islamists, the Russian Far East is not completely isolated from them.

Interaction among Islamist groups in Afghanistan, Central Asia, Russia, and China’s Xinjiang region has increased. An Islamist arc is being created from the Middle East to the Far East. According to official reports, ISIS recruits militants all along the arc to send them to the Middle East. Islamist cells of various nationalities are formed everywhere, with migrants from Central Asia playing the leading role there.

Jihadists, now well-trained and with combat experience, are returning to Central Asia, from where they go to Russia, including its Far East. Moving from Western Asia to East Asia with the help of their allies, they build up contacts and ties and draw ever more members into their networks. It is not ruled out that an Islamist bridgehead may appear in the Russian Far East and its influence will extend beyond Russia. Even a cursory glance at the map is enough to see that hotbeds of radical Islam are all over Eurasia. It is hard to name a large city in Russia that would be free from any presence of Islamists. It is believed that Chukotka is the only Russian region free from radicals. On the other hand, the same was said about the Russian Far East only recently.

The changing ethnocultural composition of the Far Eastern Muslim community requires tracking migration flows from Central Asia, as well as from Russian regions populated by Muslims, in particular the Urals and Western Siberia.

It is known that there is a network of Salafi groups and Hizb ut-Tahrir cells across Russia and that ISIS emissaries have penetrated into the country and started recruiting new members. There is a danger that ethnic and religious enclaves (even though small ones) may appear in Russia, which may exacerbate ethnic tensions (luckily, such a scenario has been avoided in the majority of Russian regions, including Moscow). It is also noteworthy that ethnic Russians have begun to convert to Islam. It is known from international and Russian experience that Muslim neophytes are especially prone to radicalism. One should know what kind of religious teaching is practiced in mosques, and what sermons clergymen preach. On the other hand, one should be tactful when working with Muslims, making sure not to provoke them and to avoid senseless bans on religious literature.

Preventing the growth of extremist threats in the Russian Far East and the Asia-Pacific region as a whole requires efficient coordination of joint efforts and improvement of the operational work of the states concerned and international organizations (SCO, CSTO) to ensure the proper level of security in the region.