For citation, please use:

Kozhanov, N.A., 2022. Iran’s Economy under Sanctions: Two Levels of Impact. Russia in Global Affairs, 20(4), pp. 120-140. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2022-20-4-120-140

The 2010–2015 sanctions cut Iran from the international banking and insurance systems and limited its access to foreign investments, advanced technologies, and international sea carriage services. Tehran’s options to sell oil on external markets and import gasoline were also curbed. Consequently, the adoption of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, the so-called nuclear deal) signed between Tehran and the international group of negotiators in 2015 was welcomed by the Iranian population and a large part of the country’s elite (BBC, 2015). This document lifted most of the previously imposed nuclear-related sanctions and gave Iran hopes for less troubled economic development. However, in 2018 the decision of U.S. President Donald Trump to quit the JCPOA changed the situation for Iran once again. The re-imposition of U.S. sanctions caused significant concerns among the international community in that Iran might not overcome another blow to its economy and political system. Yet such pessimistic expectations have not come true.

Were the Sanctions Effective?

True, the international sanctions did have an effect on the Iranian economy. The period of 2012–2015 (after the EU supported the oil embargo against Iran and till the nuclear agreement) was the most difficult for the country. By mid-2013, both the Supreme Leader of the country, Ali Khamenei, and then President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had to acknowledge that Iran’s economy was seriously damaged by the external pressure (Torbati, 2012). During the period of 2011–2015, Iran’s oil production and export fell from 3.8 and 2.4 million barrels per day to 2.3–2.7 and 0.9–1 million barrels per day, respectively (see Table 1). In 2013, a year after the introduction of the EU’s oil trade embargo, the volume of Iran’s oil revenues was almost 50% lower than those in 2011. By 2015, the decline was even deeper and reached 70%. This substantial drop inevitably caused a deficit in the Iranian budget that was heavily dependent on the inflow of petrodollars. Under these circumstances, the growth rate of Iran’s GDP in 2012 was estimated at -7.4%, with official inflation of 26% and the consumer price annual growth rate above 32%. Inflation continued to grow, reaching 40% in 2013 (see Table 1).

The lack of budget funds negatively affected government programs aimed at developing the oil, gas, and petrochemical industries. In 2012, Iran was able to invest $21 bn in the oil sector. A year later, the figure was about $17 bn. According to some experts, if the JCPOA had not been signed in 2015, the volume of Iran’s investments in the oil industry would have created a situation where the country could have received only $30 bn from its oil exports. The oil revenues were even lower than those Iran received from oil trade in 2014, which brought the country $52 bn (see Table 1). Under these circumstances, the development of some oil fields (such as Yaran, the North and South Azadegan oil fields) and the infrastructure connecting them to the export terminals was put on hold or slowed down, while successful implementation of these projects could have increased Iran’s oil output by 600,000 to 700,000 barrels per day.

During the 2012–2013 period, the fluctuations of exchange rates on Iran’s foreign exchange market were probably one of the most serious stress tests for the country’s economy. In July 2012, the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) was unable to control the overpriced exchange rate of the Iranian rial and had to depreciate it. The U.S. dollar’s exchange rate grew from 18,000 rials in January 2012 to 33,500–34,500 rials in March 2013 (on the free market). Moreover, the growth of the dollar’s value was not steady: in 2012–2013, it suddenly jumped at least four times, causing serious socio-economic shocks. One of the most dangerous situations occurred in early October 2012, when another plunge of the rial-to-dollar exchange rate on the free market not only led to the deficit of dollar banknotes in Iran but also to the closing of the Grand Tehran Bazaar and caused civil unrest in the capital (Guardian, 2012a).

The depreciation of the national currency, lack of petrodollars, and problems with the import of some consumer goods boosted the growth of prices in Iran and even caused crises on some commodity markets (Guardian, 2012b). Social indicators also demonstrated negative tendencies. According to different sources, in 2013, about 60% of the population lived either on or below the poverty line. The wealth gap was huge and kept growing. The income of the three richest deciles of the population was 15-16 times higher than that of the three poorest deciles. In 2012, the official unemployment rate reached 12.2% (more than 19% in unofficial calculations). The termination of industrial projects requiring foreign technologies, investments and equipment only sped up the growth of this indicator (Trading Economics, 2019).

Nevertheless, although the sanctions came as a serious test for Iran and harmed its economy, they did not lead to its collapse. The period of 2010–early 2013 was the most critical for Tehran. However, in 2013–2015, a trend towards economic stabilization emerged in the country. In 2013, the GDP growth rate was still negative at -0.2% against -7.4% in 2012. In 2014, the economy showed a positive growth (4.6 %). After 2014, inflation also slowed down, falling below 10% in 2016 (see Table 1). Furthermore, the dependence of the budget on oil revenues also decreased. In 2013–2014, it was 40%, but hardly reached 33% in 2015 (Financial Tribune, 2017).

The supporters of sanctions argued that the positive tendencies in Iran’s economy after 2013 were a result of Hassan Rouhani’s victory in the presidential elections in June 2013. They claim that Rouhani had a more effective economic policy. Apart from that, he proved to be more efficient as a diplomat as he launched a new round of negotiations with the international community. This compelled the U.S. allies to be less consistent in implementing the sanctions. Of course, these factors can explain some of the positive changes in Iran’s economic performance, but, as it will be shown below, the key reason for the failure of the sanctions in breaking the Iranian economy was a complex of domestic and foreign-policy measures taken by the Ahmadinejad government to counterbalance the negative effect of the external pressure.

Iran’s Response to the U.S. Sanctions

Firstly, the Iranian government was fast to learn how to live when oil revenues were limited. The new Iranian budget for the Iranian year of 1392 (March 2013-March 2014) was based on an assumption that the volume of oil exports would stay under 1.33 million barrels per day with the average price of $90-91 per barrel. The Iranian calculations were “largely reasonable: “it … [was]… difficult for the West to reduce Iran’s exports below … 1.3 million barrels per day or drive its earnings below $91 per barrel,” while petrodollars were to fund only 40% of the budget, which was considerably lower than the share of oil income in the previous budgets (usually from 60 to 80%) (Clawson, 2013).

Under these conditions, sanctions triggered what was previously considered hardly achievable: they compelled the Iranian government to convert its promises to diversify the sources of budget revenue into practical steps. Thus, in December 2012, the Iranian government declared that during the 2010–2012 period it had managed to create a modern fiscal system in the country, including a value added tax collection mechanism. Subsequently, the officials in Ahmadinejad’s Cabinet stated that it was time to start using this system and increase budget revenue. Although these statements caused a negative reaction of the Majlis (Iranian parliament), in 2012, the Iranian government increased tax revenue by collecting up to $14 bn (25% more than in 2011) (Clawson, 2013).

The diversification was not limited to taxes. In 2012–2013, Tehran boosted the development of almost all economic activities that could not be hurt by sanctions or where sanctions had a minimal impact. Tehran intensified the development of its basic non-oil industries such as steel, cement, and energy production as well as mining. Even before 2012, Tehran generated more than $10 bn a year through its petrochemical exports (Tehran Times, 2012). Although the import of equipment and technologies required for the development of the petrochemical industry was severely restricted by the sanctions, the Iranian authorities found a way to bypass these restrictions. First of all, the Iranian government placed special emphasis on the participation of private companies in the construction of relatively small refineries with refining capacities of up to 10,000 barrels per day. These refineries did not require advanced technologies and could operate using obsolete equipment produced in Eastern Europe and former Soviet republics.

As a result, “while still important, oil was becoming a smaller part of Iran’s trade. In 2012, the country’s non-oil exports accounted for 60% (and according to alternative sources, 75%) of its total exports (compared to 24% in 2002 and 14% in 1992).” What was more important is that Iran “produced this shift in part by converting more of its oil into industrial products for export” (Clawson, 2013). Thus, in 2012, Iran’s non-oil exports accounted for $37.69 bn. In 2014, they were already estimated at $46 bn. This increase in income was guaranteed by the growth of petrochemical products in the structure of Iran’s exports: gas condensates, propane, methanol, butane, and polyethylene became the main items exported abroad (Iran Project, 2019).

The growth of non-oil exports was partly stimulated by the government support programs. In 2012–2013, the Iranian authorities revised the legislation regulating exports. Some export tariffs were lowered (or even partly abolished) and about twenty programs providing subsidies and tax exemptions for the manufacturing companies were adopted. These programs were financed by the National Development Fund using the reserves made by 20-percent budget payments from oil revenues.

The fall of the rial against the U.S. dollar logically made foreign trade extremely profitable for some Iranian companies in the petrochemical, construction, and agricultural sectors.

By 2013, the country’s political and economic elite had become unanimous in that it was necessary to buy the loyalty of the lower classes. Despite decreased oil revenues, they continued to allocate huge sums of money in direct and indirect social subsidies. That is why some of the populist programs organized and implemented by Ahmadinejad did not find much resistance among his opponents. For instance, in February-March 2013, the President sponsored a program by which every Iranian received an assistance payment of $65-82 for the March 21 Nowruz (Iranian New Year). He also set a favorable official rate of 12,260 rials to the dollar, which was used to set the price of basic goods in government-regulated outlets.

The government paid special attention to the management of the foreign exchange and financial markets. In a bid to cope with the consequences of the inevitable depreciation of the national currency, Tehran tightened control over foreign exchange transactions and re-introduced a multiple exchange rate system that allowed it to allocate cheaper foreign currency to the importers of essential goods. The Iranian authorities imposed a ban on the import of luxury commodities to decrease the outflow of hard currency from the country. With the same goal in mind, non-tariff methods were introduced to limit the import of goods whose equivalents were manufactured in Iran. At the same time, duty free imports of gold and silver bullions were allowed, which Tehran started to use in its foreign transactions.

Thus, during this period of Western sanctions the Iranian leadership learned several important lessons and gained valuable experience in counterbalancing the negative impact of sanctions that it could use in the future. First of all, the years of 2010–2015 demonstrated that the Iranian economy had a certain strength reserve that helped Tehran overcome the initial negative impact of sanctions. Secondly, the 2010–2015 period also showed the importance of decisive measures for strengthening the domestic economic capacities to fight sanctions. Finally, it helped work out steps to curb the negative effect of the U.S. sanctions. Consequently, when in May 2018, the U.S. authorities decided to quit the JCPOA, the Iranian leadership already had a set of measures in place to cope with the negative impact of the reimposed sanctions.

The 2010–2015 Sanctions and Foreign Trade

No less important for evading sanctions were measures undertaken by Tehran in the international arena. Firstly, it stepped up interaction with its traditional trading partners, trying to ensure their loyalty to Iran and encourage them to counter the sanctions imposed by the United States and its partners. For instance, after the introduction of oil embargo by the EU in 2012, Iran offered substantial price discounts for the remaining buyers of its hydrocarbons in order to win over their loyalty.

In certain cases, the very nature of the sanctions created opportunities to bypass them: the punitive measures were mostly related to sea and air transportation whereas road haulage was left without attention. Meanwhile, Iran’s highly developed domestic road infrastructure had multiple junctions with the transportation systems of the neighboring countries, which allowed Iranians to deliver goods to every point in Eurasia without using sea or air routes. As a result, notwithstanding the sanctions imposed in 2010, the media reported a certain increase in the number of petrol tankers crossing Iran’s borders with Turkey and Iraq and ferried across the Caspian Sea from some Central Asian countries.

The Iranian authorities also used illegal measures. For instance, in 2010-2015, they were periodically accused of attempts to sell oil covertly. Some say that the easiest scheme for Tehran was to falsify documents and sell its oil as if produced in Iraq. Another scheme implied engaging companies established in the neighboring countries (such as the UAE) whose oil tankers were periodically reported “accidently” floating near the Iranian coast and subsequently arriving to destination ports with loads of oil. One of the probably most extreme methods to conduct secret trade operations with oil was related to its ship-to-ship transfers in the open sea. During the period of 2010–2015, Tehran increased its tanker fleet (not only by constructing new ships but also by buying old oil tankers that were prepared for scrapping). These oil tankers periodically would leave Iranian ports without stating the exact point of destination and could stay in the open sea for some time. If an oil deal was concluded, such a tanker turned off its tracking beacons to hide its position and moved to an agreed point where it met a tanker of the buyer. The load was transferred from one ship to the other in the open sea. After this, the Iranian empty tanker returned to its home port (Drummond and Khalaj, 2011).

The ways to evade sanctions in the banking sector were no less sophisticated. Initially, the Iranian authorities approached the governments of different countries with the initiative to establish joint banks with offices opened in both countries. By 2010, such offers had reportedly been sent to the governments of Russia, India, China, and Turkey. The creation of such banks would provide for direct transactions between countries without the involvement of Western banks and dollar transactions. However, except for the Iran-Venezuela Joint Bank that was inaugurated by Ahmadinejad and late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez in Tehran in 2009, the project did not go any further. So, Tehran chose another strategy: it began to use the national currencies of its main trading partners as legal tender in foreign-economic activities instead of dollars and euros. This measure became extremely important after the adoption of the 2010 sanctions that seriously limited Tehran’s capacity to use dollars. In 2015, Iranian banks were already able to conduct transactions in the Korean won, Turkish lira, Chinese yuan, Japanese yen, Indian rupees, and Emirati dirham.

To avoid additional troubles with international transactions, Iranian businessmen often chose to receive their export earnings not as wire transfers to their accounts in Iranian banks but in the banks of foreign countries. For instance, after the adoption of the 2010 sanctions, the Korean government allowed Iranians to keep financial resources earned from the export of oil to the Republic of Korea in accounts in the Industrial Bank of Korea and Woori Bank. This money was supposed to be later used to buy Korean products and import them to Iran. These decisions by the Iranian and Korean authorities led to the establishment of direct links between the countries and excluded the unnecessary foreign-exchange operations in dollars that could have been hurt by the U.S. sanctions in 2010–2012. Almost the same scheme was used in Turkish-Iranian economic contacts. Part of the money received by the Iranian companies for the export of oil and gas to Ankara was left in the accounts of Turkish banks. Subsequently, these funds were either spent to finance the import of consumer goods from Turkey, or to buy precious metals and stones. The latter were also imported to Iran where they either replenished gold and foreign currency reserves of the Islamic republic or were used as legal tender to pay for imported commodities.

The use of gold and silver as a means of payment for goods bought abroad clearly illustrated the Iranians’ ability to employ the simplest methods to handle difficult situations. Being cut off from the international banking system, the Iranians tried to exclude banks from their economic operations where possible. Since 2010, I could often hear stories from Iranian businessmen about how they do business abroad by literally carrying suitcases full of cash with them. Alternatively, they could use hawala—an informal money transfer system based on a huge unofficial network of money brokers in the Muslim communities around the world which is not connected to the international financial system. Where hawala or cash payments were inapplicable, the Iranian authorities conducted barter deals. For example, in 2012–2014, India paid for part of its oil imports from Iran with food produce (Gladstone, 2013).

The JCPOA as a Test for the Iranian Economy

Yet, although Iran was surviving under the 2010–2015 sanctions, it was not developing. Under these circumstances, the lifting of sanctions became one of the top priorities for Tehran. The beginning of the constructive dialogue with the international community and subsequent adoption of the JCPOA helped ease the sanctions burden and launch the process of the country’s gradual reintegration into the global economy. First and foremost, the JCPOA lifted limits on the export of Iranian oil and thereby helped increase the country’s budget revenue. After 2015, foreign businesses started to investigate investment opportunities in Iran. This process was accompanied by partial restoration of Iran’s ties with the international banking system. However, although in 2015–2018, the Iranian leadership was successful in starting the recovery of the country’s economy, it could not ensure its sustainable growth and the improvement of social conditions. There were several reasons for that.

Firstly, the United States, unlike other players, did not completely remove its extraterritorial sanctions. Washington justified this by referring to Iran’s regional policies (which it considered aggressive), the human rights situation in Iran, and alleged facts of money laundering by the Iranian authorities. As a result, most of the financial sanctions imposed by the United States remained in place, and only nuclear-related sanctions were lifted. This prevented complete restoration of Tehran’s ties with the international financial system and made potential investors very cautious about funding projects in Iran. In addition, in 2015–2016, foreign companies were not sure whether Obama’s successors would honor the JCPOA and adhere to its principles, which increased political risks associated with investments in Iran. The election of Donald Trump in 2017 only strengthened their belief that it was too early to return to Iran. By the mid-2018, these concerns appeared fully justified.

Secondly, while most sensitive sanctions imposed in 2010–2015 were lifted by the EU, Iran’s economy continued experiencing their negative repercussions. For instance, due to the lack of access to foreign technologies and equipment and external investments during the sanctions period, Tehran could not promptly modernize the production base and repair fixed assets of its enterprises in key industries. Consequently, by 2015 a large part of these enterprises had been either broken down or outdated and faced a high degree of depreciation. In some industries, such as steel production, for instance, fixed assets required almost complete replacement. This factor determined the initial huge volume of investments necessary to revitalize Iranian domestic production and make it competitive. Yet there were not enough funds available to make these investments. Iran’s domestic financial reserves were exhausted by the years of sanctions while the low profitability and high investment risks associated with the U.S. policies towards Iran did not allow foreign investors to step in and remedy the situation.

Whereas in 2016, the country’s economy showed a 13.4% growth (after a -1.3% drop in 2015), in 2017, this figure was only 3.8% (see Table 1). Moreover, improved economic performance did not lead to the improvement of social indicators: after a slight decrease in 2016, in 2018, the unemployment rate returned to the level of 12.5% (according to official reports). The depreciation of Iran’s currency continued, which was accompanied by a gradual decrease in the purchasing power of Iranian households and high consumer price growth rates (see Table 1). In 2015–2017, the price of some foods grew by as much as 20%. The wide gap between the rich and the poor remained unchanged, and so did the share of the population attributed to the low-income strata. Iranian young people were the most socially vulnerable section of the population, with the level of unemployment among them estimated at 40% (Abdallahi, 1397 (2018), pp. 4-6).

The adoption of the JCPOA also clearly demonstrated that it would be wrong to blame sanctions alone for all misfortunes of the Iranian economy. Other key factors, which did not allow the country to develop during the short period when the sanctions were eased, included the structural deficiencies of the Iranian economy. The dominant role of the government in the economy, high administrative costs, a substantial size of the gray sector in the economy together with the low effectiveness of the private sector, and the underdevelopment of market mechanisms aggravated by protectionist policies that created artificial favorable conditions for Iranian producers are among the key factors that continued to negatively affect the Iran’s economic development after the sanctions were lifted.

Iran’s persisting problem is the need for deep structural economic reforms, including the need to further cut economically unjustifiable big social programs that annually consume up to $80 bn of the country’s budget (Abdallahi, 1397 (2018), pp. 4-6). Declaring the protection of the oppressed (mostazafin) as one of the main tasks of the Islamic Republic in 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers turned populism into one of the main leverages of their domestic policy, which made the Islamic authorities eternally dependent on the support of the lower classes. This decision made the ruling regime extremely durable. At the same time, this social policy had a number of negative economic implications. Firstly, the Iranian authorities were compelled to buy the loyalty of their supporters, and, since 1979, one of the main measures used by the government to gain the support of the lower-income segments of the urban population was consumer subsidies and provision of cheap basic products. As a result, during the last four decades, the Iranian authorities created an intricate system, which has allowed them to influence and control the import, production, and distribution of the main consumer goods. However, the system imposes a heavy burden on the country’s budget. Subsidies and extensive social programs have been “consuming” the financial assets that could be used to develop the country’s economy. Also, this system has turned the government into the main (if not the only) instrument that regulates relations between producers, importers, retailers, and consumers, and has almost excluded market economy mechanisms from this process. Eventually, government involvement, limited market freedom, and lack of market competitiveness has become the curse of the Iranian business environment that suppressed private initiative and discouraged foreign investments.

Iranian economic problems have also been exacerbated by banking regulations. Exclusive reliance on the ideas of Islamic economics and a ban on the Western models of banking have forced Iranian banks to choose a special path for development. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the financial sector of the Iranian economy and Iranian social activities were brought in line with the requirements of the Quran. Firstly, a strict ban was imposed on the use of interest rates in their traditional meaning. The banks were to take part in projects of their borrowers, sharing with them not only profits but also risks. As a result, the Iranian financial institutions largely lost interest in the development of loan programs and became vulnerable to systemic fluctuations in the Iranian economy. State control, lack of competition, and seclusion from the outside world led to stagnation in Iran’s banking system and weakened its role in the national economic development.

Despite the obvious need for economic reforms, it was, and still is, difficult to implement them in Iran. On the one hand, reforms in the banking sector and social programs would inevitably go against some ideological principles of the ruling political system in Iran that has declared the protection of the social and economic interests of low-income groups of the population one of its key priorities and incorporated Islamic elements in the country’s management system. On the other hand, the Iranian leadership tried to avoid any reforms that could negatively affect the socio-economic situation while the country was experiencing substantial external pressure. Under these circumstances, the adoption of the JCPOA and partial ease of the sanctions regime gave the authorities a window of opportunity for bringing certain changes into the economy while the country was not under heavy economic pressure from abroad. Unfortunately, this opportunity was missed with Trump’s decision to withdraw from the JCPOA in May 2018.

Iran’s Economy and Sanctions after 2018

Putting aside the negative impact of COVID-19 on Iran’s economy that might create certain distortions in the overall picture of the sanctions war between Iran and the U.S., the current round of the economic confrontation has a lot in common with the 2010–2015 period: while in 2018–2019, the country had to live through a time of severe economic turbulence (see Table 1), in 2020 and thereafter it managed to restore control over the situation and even to demonstrate some positive growth trends (Abdallahi and Banitaba, 1401 (2022)). This can be explained by both the similarity of challenges faced by Iran during both rounds of sanctions and the extensive experience of counteraction that was accumulated by the country’s leadership in 2010-2015.

The previous period clearly showed that there are, at least, two levels of sanctions’ impact on Iran’s economy:

- Immediate and direct impact (first-level impact);

- Long-term cumulative impact, whereby results become obvious over time but the effect is usually much stronger than that of the immediate impact (second-level impact).

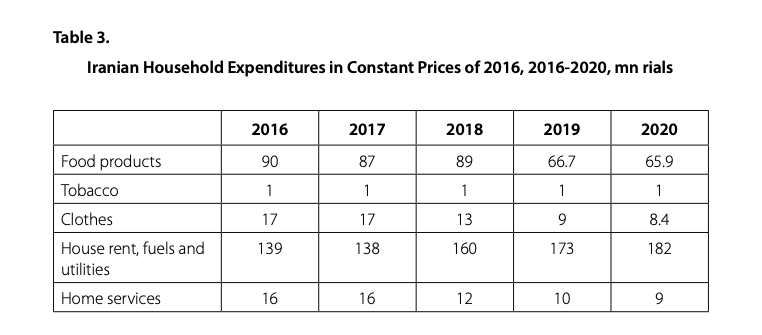

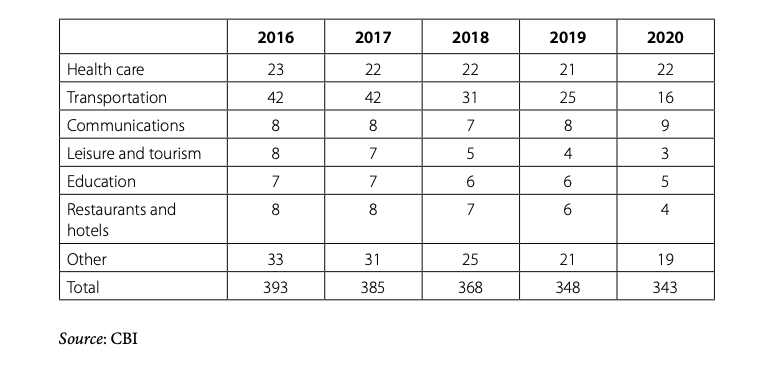

The sanctions boosted inflation, depreciated the national currency, and pushed consumer prices up. According to the CBI official statistics, in comparison to the 2016-2017 market situation, consumer prices for domestic products in 2018, 2019, and 2020 increased by 31%, 41%, and 47%, respectively. For imported goods, these figures were 138%, 16%, and 32%, respectively. The USD exchange rate on the free market grew from 103,378 rials for $1 in 2018 to 228,809 rials in 2020 (Bank, 1400 (2022), p. 38-39). Under these circumstances, the substantial increase in consumer prices of goods and services (see Table 2) coincided with a sharp drop in the purchasing power of Iranian households, leading to the destabilization of the social situation in the country (see Table 3). However, even though occasional demonstrations and protest actions became a new daily reality of Iran, the government managed to cope with the situation.

The 2010–2015 sanctions experience clearly allowed Tehran to create and test different economic methods of dealing with the first-level impact of sanctions. These include the support of national business champions and those industries that are important for the survival of the economy under sanctions. It also suggests the improvement of the tax system, further promotion of economic diversification and allocation of additional resources to buy the loyalty of the people and stop the decline in the purchasing power of the population. In the international arena, Iran’s efforts to counterbalance the negative impact of sanctions include the smuggling of sanctioned goods, the use of national currencies instead of U.S. dollars to facilitate foreign trade, the establishment of clearing centers and more active use of barter deals, the creation of front companies abroad, the use of trackers in conjunction with oil tankers; the use of foreign small and medium-sized businesses that have little to do with the U.S. market to facilitate Iran’s needs, and the provision of discounts on its oil for consumers.

The reimposition of sanctions became one of the reasons for Iran to improve its relations with neighboring countries as it believes that good relations will help avoid international isolation and some of these neighboring countries could be used to help Iran evade the sanctions. By 2022, this had led to the intensification of Iran’s diplomatic activity in Iran’s immediate neighborhood, which was aimed at appeasing bordering countries, including the Gulf monarchies.

The self-sufficiency strategy that has been implemented by the Iranian authorities with differing degrees of success and intensity since 1979 has also brought results. While oil, gas, petrochemical production, and automobile manufacturing (as dependent on the import of spare parts and raw materials) inevitably has fallen victim to the sanctions, the external economic pressure and the fall of national currency has not substantially hurt those sectors of the economy that provide for the people’s basic needs in food, fuel, and clothes. Unsurprisingly, after the U.S. exit from the JCPOA and the restoration of U.S. sanctions pressure, the economic situation in Iran and the reaction of the Iranian government to these new old challenges repeated the patterns of 2010–2015. While the oil sector suffered the most, the petrochemical, automobile and construction sectors were also hurt by sanctions due to their dependence on imported equipment, spare parts, and raw materials, as well as due to the fall of the purchasing power of the population. However, the agricultural and service sectors were not directly exposed to the negative impact of the sanctions (Abdallahi, 1397 (2018)).

The second-level impact of the sanctions is much more dangerous for the Iranian economy as it can last longer and might not be visible in the beginning (usually, it takes years before the influence of such sanctions becomes evident). At this stage, the sanctions harm the very foundation of the Iranian economy, such as its ability to develop the production base, draw foreign investments, use long-term foreign bank loans, and enter new markets. More importantly, this impact cannot disappear immediately if and when sanctions are lifted: the backlog in the development of certain industries will remain for years as Iran has been deprived of access to new equipment and technologies. And this is where the Iranian government has failed to offer any clearly articulated solution—either in 2010-2015 or after 2018. Meanwhile, the deterioration of Iran’s production base will inevitably become the main obstacle to the country’s economic development and stable budget revenue.

According to Katzman (2022, pp. 52-54, 67), the U.S. sanctions are one of the main reasons for slowing down the development of Iran’s oil and gas sector. He points out that since 2017 no foreign direct investment has been made in any major hydrocarbon project in the country, which means that no new foreign technologies have come to the oil sector. Moreover, the sanctions have partially led to the underdevelopment of the gas and LNG sector, turning the country with its vast natural gas resources into an unimportant player on the market.

Given the ongoing global energy transformation, Iran risks to have some of its gas riches either unsold or sold not at the highest price possible. In the non-oil sector, the situation is also far from positive. In 2019–2022, not only Iran’s automobile manufacturers, but also food and textile producers have demonstrated an almost stable tendency towards contraction of production (Abdallahi and Banitaba, 1401 (2022), p.16). To cope with these challenges, the Iranian leadership will have to solve structural economic problems caused by the specifics of the Iranian economy and aggravated by the sanctions imposed by the U.S. and its allies.

* * *

Iran’s ability to withstand the immediate negative consequences of the current U.S. sanctions raises little doubts given the country’s previous experience to live under external pressure. However, sooner than later the Iranian leadership will be compelled to reconsider its economic strategy. The country will have to make certain steps to fight the deterioration of its production base due to the second-level impact of the sanctions. The success of the Iranian leadership in the revitalization of the economy and ensuring its further sustainable development will depend on several factors.

Firstly, the government should be prepared to make unpopular steps. Iran will have to reconsider its social spending to have additional funds to invest in the economy. It will have to reform the banking sector to make it more efficient. The business environment should also become friendlier to the private sector and those foreign investors that are still prepared to work with Iran. In other words, the Iranian leadership must be ready “to bless” deep economic reforms. At the same time, some past initiatives, such as the reduction of excessively big social programs and counterproductive consumer subsidies may also be useful. This is directly associated with another challenge that Iran may face in the future: structural reforms may cause a negative reaction from low-income groups of the population as the government will have to reduce the financial support to them, and also from those political groups that now profit from existing structural imbalances.

It is also important for the Iranian leadership to continue using the international factor to mitigate the negative impact of the U.S. sanctions on country’s economy. Since 1979, the economic cooperation between the U.S. and Iran has been minimal. So, the United States could exercise actual influence on the Iranian economy only through interaction with the international community (by using punitive measures and incentives to limit its abilities to cooperate with Tehran). Iran, in turn, can mitigate the negative influence of the U.S. sanctions mainly through establishing an appropriate system of international relations. In this situation the following factors are vitally important for bypassing the American sanctions:

- the attitude of Iran’s main trade partners towards the U.S. sanctions;

- the readiness of the U.S.’ partners to follow the requirements of its sanctions and implement their own punitive measures against Iran in practice;

- the readiness of Iran’s smaller trade partners to make use of the “lucrative opportunity” to increase their presence on the market of the sanctioned country left by bigger players. By so doing they can mitigate the negative effect of the punitive measures against Iran (McLean and Whang, 2010, pp. 427-447).

Abdallahi, M.R. and Banitaba, S.M., 1401 (2022). Payesh-e Bakhsh-e Haqiqi-ye Eqtesad-e Iran dar Tirmah 1401. Baksh-e San’at va Ma’dan [Overview of the Real Economy of Iran in July 2022]. Tehran: Markaz-e Pazhuhesh-e Madjles-e Shaura-ye Eslami [Parliament Research Center].

Abdallahi, M.R., 1397 (2018). Tahlil-e Tahavvolat-e Akhir-e Eqtesad-e Iran [The Study of Current Developments in Iran’s Economy]. Tehran: Markaz-e pazhukheshkha-ye majles-e shoura-ye eslami [Parliament Research Center].

Bank, 1400 (2022). Kholase-ye Tahavvolat-e Eqtesadi-ye Keshvar [Summary of the Country’s Economic Developments]. Tehran: Bank-e Mafkazi-ye Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran [Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran].

BBC, 2015. Iran Nuclear Deal As It Happened. BBC, 14 July [online]. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/live/world-middle-east-33509809 [Accessed 4 May 2019].

Clawson, P., 2013. Iran Beyond Oil? Policy Watch, 2062, 3 April [online]. Available at: http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/iran-beyond-oil [Accessed 18 August 2022].

Drummond, J. and Khalaj, M., 2011. Iran Finds Way Round Petrol Sanctions. The Financial Times, 7 February [online]. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/fabc2bba-32da-11e0-9a61-00144feabdc0 [Accessed 18 August 2022].

Financial Tribune, 2017. Budget’s Oil Dependence Declines to 30%. The Financial Tribune, 25 April [online]. Available at: https://financialtribune.com/articles/economy-domestic-economy/63082/budget-s-oil-dependence-declines-to-30 [Accessed 18 August 2022].

Gladstone, R., 2013. Iran Finding Some Ways to Evade Sanctions, Treasury Department Says. The New York Times, 10 January [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/11/world/middleeast/iran-finding-ways-to-circumvent-sanctions-treasury-department-says.html [Accessed 18 August 2022].

Guardian, 2012a. Iran Currency Crisis Sparks Tehran Street Clashes. The Guardian, 3 October [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/oct/03/iran-currency-crisis-tehran-clashes [Accessed 18 August 2022].

Guardian, 2012b. Reports of Street Protests in Iran due to Soaring Price of Chicken. The Guardian, 23 July [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2012/jul/23/street-protests-iran-chicken [Accessed 18 August 2022].

Iran Project, 2019. Non-Oil Exports Leaving Sanctions Behind. Iran Project, 18 March [online]. Available at: https://theiranproject.com/blog/2019/03/18/non-oil-exports-leaving-sanctions-behind/ [Accessed 18 August 2022].

Katzman, K., 2022. Iran Sanctions. Washington DC: Congressional Research Center.

McLean, E. V. and Whang, T., 2010. Friends or Foes? Major Trading Partners and the Success of Economic Sanctions. International Studies Quarterly, 54.

Tehran Times, 2012. Iran’s Petrochemical Exports Approaching USD11 billion. The Tehran Times, 1 January [online]. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20120204211907/http://www.tehrantimes.com/economy-and-business/94108-irans-petrochemical-exports-approaching-11-billion [Accessed 18 August 2022].

Torbati, Y., 2012. Iran Budget under Pressure, Ahmadinejad Says. Reuters, 9 October [online]. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-economy/iran-budget-under-pressure-ahmadinejad-says-idUSBRE8980X120121009?feedType=RSS&feedName=worldNews&utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+Reuters%2FworldNews+%28Reuters+World+News%29 [Accessed 18 August 2022].

Trading Economics, 2019. Iran Unemployment Rate. Trading Economics, January [online]. Available at: https://tradingeconomics.com/iran/unemployment-rate [Accessed 24 March 2022].