The pan-European process that was given the go-ahead at the

Helsinki Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe in

August 1975 will mark its 35th anniversary in 2010 and the signs

are that congratulations on this occasion will be received by

Kazakhstan as the country that will preside over the Organization

for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in that year. For the

first time in the history of this organization, its rotating

chairmanship will go to a country that is not only Asian, but which

also has a controversial list of problems with democracy and human

rights – the areas that the OSCE traditionally places high on its

agenda.

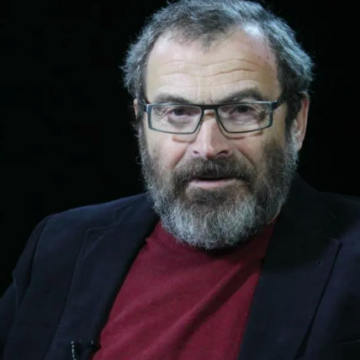

According to Muratbek Imanaliev, a former Kyrgyz foreign

minister and current president of the Bishkek-based Institute of

Public Policy, the accession of Central Asian countries to the

European regional security organization in 1992 was “a historical

and political caprice prompted by events of the early 1990s and by

certain predilections of leading powers.” The Kazakh path toward

chairmanship of the largest European organization has been full of

twists and turns and it reflects not so much the rise of the

country’s national statehood, as the rivalry between Russia and the

West for energy resources in the Caspian basin and Central Asia,

plus the competition between Moscow and the Kazakh government for

positions in energy markets and in the territory of the former

Soviet Union.

RAKHAT ALIEV’S CAVALRY CHARGE

In February 2003, Rakhat Aliev, Kazakhstan’s ambassador to

Austria and to the OSCE, made a request at a session of the OSCE

Permanent Council to consider Kazakhstan as an aspirant for the

organization’s rotating chairmanship due to begin in 2009. Quite

naturally, Aliev, a son-in-law of Kazakh President Nursultan

Nazarbayev, was not viewed as a regular diplomatic official, yet

few people took his request seriously, as Astana’s relationship

with the OSCE was more than simply strained at the time.

Back in 1999, Nazarbayev openly accused OSCE representatives of

meddling in his country’s domestic policies after he had undergone

sharp criticism for extending his presidential powers in an early

election. He said in an interview with the Habar television channel

that OSCE officials were acting like Soviet-era functionaries who

would come to Kazakhstan from Moscow for inspections. Nazarbayev

also made it clear that his country did not consider membership in

the OSCE indispensable.

The U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Asia, the

Pacific and the Global Environment endorsed Resolution 397 in

September 2000, voicing concern over the situation with human

rights and democracy in Central Asia, including Kazakhstan, and

calling into question their membership in the OSCE in the

future.

Kazakh Foreign Minister Yerlan Idrisov responded in November of

that same year as he addressed the eighth session of the OSCE

Ministerial Council in Vienna. He accused the OSCE of giving much

more attention to human dimension issues in detriment to military,

political, economic and ecological issues. His conclusions sounded

tough: the evolution processes in the OSCE did not meet

Kazakhstan’s requirements and the organization handed down

predominantly negative, biased and tutorial assessments of the

situation in the country.

Relations seemed to have returned to the old track and

ambassador Aliev’s unexpected statement was drowned in oblivion. In

October 2003, Kazakhstan’s mission to the OSCE released a

confidential memorandum On Reforming OSCE Operations in the

Regions. The six-page document accused the OSCE of being overly

bent on human rights. It also said the organization had “focused

the bulk of its attention on human dimension issues in separate

regions” and had “erroneously rejected dialog on these problems

with the authorities of the countries in question, concentrating

instead on independent assessments, often based on subjective

judgments and unverified information.”

The memorandum leveled sharp criticism at OSCE country missions,

whose members mostly contacted non-governmental organizations and

human rights groups. Kazakhstan recommended forming missions in

coordination with the authorities of each country in question and

limiting their mandates to twelve-month periods with the

possibility of extending them only through a decision of the OSCE

Permanent Council. Moreover, it was proposed that mission personnel

rely on governmental structures in their work.

The document emerged in the run-up to Nursultan Nazarbayev’s

speech at a session of the Permanent Council, scheduled for

November 20, 2003. Rakhat Aliev’s efforts to rally support for the

memorandum among the ambassadors represented at OSCE headquarters

failed to deliver results. On November 18, the presidential press

service said: “Nursultan Nazarbayev has been admitted to the

Republican Clinical Hospital in Astana for inpatient treatment for

a catarrhal disease, and his visit to Austria scheduled for

November 20, in the course of which he planned to address the OSCE,

is henceforth postponed.”

It is not clear what motives were behind Aliev’s cavalry charge

on the OSCE mechanisms. The proposals called into doubt the

organization’s founding principles formulated in the humanitarian

“Basket III” of the Helsinki agreements. However, it should be said

that the events of five years ago anticipated the major motives of

a brawl between Moscow and the OSCE during the Russian

parliamentary and presidential elections at the end of 2007 and the

beginning of 2008. One more possible reason for the breaking down

of Aliev’s assault was a lack of active support from other CIS

countries (although the preamble of the memorandum said it had been

drafted in cooperation with the Russian, Belarusian and Kyrgyz

missions). Now Moscow is trying to counteract the OSCE alone, and

it looks like Kazakhstan has no plans to support Moscow – something

that will be discussed below.

“THE CLEANSING TIDE OF THE DEMOCRATIC PROCESS”

Astana’s approach began to change in 2004 when Rakhat Aliev and

his wife Dariga Nazarbayeva, the eldest daughter of the Kazakh

president, started cooperating with U.S. Global Options, a company

which collaborated with some former U.S. high-ranking

administration and defense officials. Some details of this came

into the spotlight in spring 2008 following publications in the

U.S. media.

The Wall Street Journal claimed, among other things, that Dariga

tried to make Global Options instrumental in exerting influence on

the course of an investigation into a corruption scandal, which the

international media has labeled Kazakhgate. Its main figure, the

U.S. financier James Giffen, is suspected of corrupting the highest

Kazakh state officials, including Nazarbayev.

The president himself dismissed in May 2004 the reports on his

involvement in Kazakhgate. U.S. ambassador to the OSCE, Stephan M.

Minikes, made an undiplomatically straightforward remark when he

visited Astana several days later. His diagnosis suggested that

corruption was a malignant tumor eating away at the country from

the inside. He also issued a prescription against it – to plunge

into “the cleansing tide of the democratic process.” As the

discussion of Kazakhstan’s application for the OSCE chairmanship

was getting closer, Minikes urged the country’s leadership to grasp

at this “great opportunity” and to clean up its reputation by

ensuring free and fair parliamentary and presidential elections,

due in 2005.

Sources close to Aliev claim it was precisely then – in 2004 –

that his partners in Global Options recommended that he give up

confrontation with the OSCE and start looking for a “European” path

for his country.

New initiatives from Russian diplomatic quarters came at about

the same time. They aimed at rectifying a situation where the OSCE

had the function of an “instrument” in “serving separate countries

or groups of countries”. The text of a joint statement by CIS

members of the OSCE, with the exception of Georgia, initiated by

Moscow, was made public at a session of the Permanent Council in

July 2004.

The organization was reproached for its inability “to adapt to

the reality of a changing world and to ensure an efficacious

solution to security and cooperation problems.” Rebukes also

concerned non-observance of the Helsinki principles, such as

non-interference in internal affairs and respect for the

sovereignty of separate states. CIS countries proposed working out

“standardized unbiased criteria” for the “assessment of elections

in the entire territory of the OSCE”, to reduce the size of

observer missions to fifty members, and to forbid commenting on

elections by mission members before the official publication of

results.

“A RARE OPPORTUNITY”

The Kazakh parliamentary election on September 19, 2005 was

intended to become the most decisive argument in favor of

Kazakhstan’s bid for the OSCE chairmanship. Nazarbayev himself did

his utmost to lobby Kazakhstan’s interests among the ambassadors at

OSCE headquarters a week before the vote. Diplomatic sources in

Vienna told the author of this article at the time that Nazarbayev

was given to understand that Western countries would welcome

Kazakhstan’s voluntary withdrawal of its application for

chairmanship. Turkey, for instance, which aspired to the

chairmanship in 2007, went back on its claim in view of an

insufficient level of democratic freedom in the country.

Observers from the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and

Human Rights (ODIHR) issued an uncompromising verdict on the

election in Kazakhstan, saying that it had failed to meet the

international standards specified by the OSCE, but this assessment

did not discourage Astana. “Tying the decision on chairmanship to

the assessment of elections does have importance, but one must also

think about the prospects for democracy in Kazakhstan,” Kasymjomart

Tokayev, the foreign minister at the time, said in an interview

with the Vremya Novostei newspaper.

“Being a Eurasian country, Kazakhstan reflects the current

character of the OSCE, as purely Asian countries of our region also

have membership there,” Tokayev said. “Our country has done a lot

of work in terms of moving toward democracy and it needs a bonus of

some kind […]. That is why we believe that Kazakhstan is a worthy

candidate for chairmanship of this respected international

organization.”

In May 2008, six months after Kazakhstan had received the

much-desired right to hold the reins of the OSCE, albeit in 2010

and not in 2009, the country’s State Secretary Kanat Saudabayev

talked about a “rare opportunity” the chairmanship would offer “for

strengthening of the dialog between the East and the West.” “When

we say ‘East’ in this case, we mean both OSCE member-states located

east of Vienna and countries of the Muslim East,” Saudabayev said

while sharing his geopolitical findings.

However, Kasymjomart Tokayev did not feel any special enthusiasm

in November 2005, a month before the presidential election. “Our

intentions will not materialize overnight,” he said in a comment on

Western recommendations to democratize the electoral system in

Kazakhstan. “I agree that the upcoming election must be fair and

free of infringements on the rights of the opposition, although I

do not have any doubts about the results of voting,” Tokayev

said.

The results did look stunning, as the official returns showed

that 91.01 percent of the electorate had voted in favor of

President Nazarbayev. OSCE mission coordinator Bruce George said

the election “did not meet a number of OSCE commitments and other

international standards for democratic elections.”

The prospects were far from bright for Astana until December

2006, when the destiny of Kazakhstan’s chairmanship was to be

decided at a session of the OSCE Ministerial Council in Brussels.

However, Britain’s new ambassador to Kazakhstan, Paul Bremmer, who

arrived in Astana in January 2006, noted the importance for

Kazakhstan to show its commitment to the OSCE principles during the

rest of the year. He indicated that more progress could be expected

in the entire field of democratization. Bremmer recalled the ODIHR

report on the presidential election that had highlighted some

encouraging facts and had at the same time pointed out areas where

more work was still needed.

Nazarbayev personally came to Brussels several days prior to the

meeting to support his country’s bid. He chose as a pretext for his

visit to Belgium (his high status ruled out his presence at a

ministerial meeting) the signing of a memorandum on mutual

understanding between Kazakhstan and the European Union in the

energy sector. After a meeting with European Commission President

Jose Manuel Barroso, Nazarbayev said it would be extremely

important to rally EU support for Kazakhstan’s candidacy, since

“peaceful coexistence among people of 130 different nationalities

and 46 religions in Kazakhstan” presented the OSCE with invaluable

experience. This statement put Barroso in a rather awkward position

and prompted him to make a tough answer by saying: “I’m sorry, but

the European Commission has absolutely no position on this, that’s

not our need to solve.”

Despite support from Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands,

no consensus was reached in Brussels to award Kazakhstan the

chairmanship in 2009. Britain and the U.S. voted against it, and

attempts by Belgian Foreign Minister Karel de Gucht to persuade

Astana to voluntary postpone its bid until 2011 (he specially went

to a CIS summit in Minsk before the session in Brussels in a bid to

meet with Nazarbayev’s representatives there) proved

unsuccessful.

A decision was postponed until the November 2007 session that

the Ministerial Council was due to have in Madrid. Germany’s expert

for Central Asia and the director of the Eurasian Transition Group,

Michael Laubsch, said the failure of the meeting in Brussels was

“unique” for the OSCE, as this was the first instance in the 30

years of the organization’s history that its member-states would

fail to reach a consensus on leadership within their ranks.

“OUR KAZAKH FRIENDS” PLAYING THEIR OWN GAME

The year 2007 started out with dramatic events in Kazakhstan.

Two top managers of Nurbank – where Rakhat Aliev, who by that time

had been promoted to First Deputy Foreign Minister, was the largest

shareholder – were kidnapped and quite possibly killed in January.

In February, Nursultan Nazarbayev dismissed his son-in-law from the

post and sent him to Vienna for the second time as ambassador to

Austria and the OSCE. In late May, the president issued an order

“to conduct a scrupulous investigation regardless of the official

position and status of the people involved” into the kidnapping of

the Nurbank managers. Aliev, who was accused of taking part in this

and other crimes, managed to flee Kazakhstan and seek political

asylum in Vienna. Nazarbayev’s reaction to this was pretty tough –

he fired Aliev from all the posts, compelled his daughter Dariga to

divorce the man in absentia and placed his former son-in-law on the

international wanted list.

This situation made Nazarbayev forget about the bid for OSCE

chairmanship for the time being, especially as on May 21 – several

days before the institution of a criminal case against Aliev –

Nazarbayev signed a decree that introduced amendments to the Kazakh

Constitution. They envisioned among other things “a transition from

a presidential to a presidential-parliamentary form of government”

and allowed him to run for president an unlimited number of

times.

It was obvious that Nazarbayev’s decision to declare himself de

facto president for life, which heavily undermined the chances for

Astana to get the much-desired OSCE chairmanship, was dictated by a

fight for power among his closest associates and Rakhat Aliev’s

stated readiness to compete for the presidential post in five

years.

As the next step, Nazarbayev dissolved parliament – for the

third time in 17 years – and scheduled early elections for August

18, 2007. Only one political force – the pro-presidential

superparty Nur Otan – proved able to get past the seven-percent

support barrier at the polls, thus returning the country to

one-party rule. Ljubomir Kopaj, the head of the OSCE mission to

Kazakhstan, did not conceal his dismay, saying he did not know any

democratic country where only one party would be represented in

parliament.

However, it became clear the next day after the election that

Astana had not forgotten the OSCE chairmanship project for good.

Nazarbayev filled the vacant seat of the ambassador to Austria by

sending Deputy Foreign Minister Kairat Abdrakhmanov there. In the

very same days, Rakhat Aliev sent a SOS to his former counterparts

in OSCE headquarters, urging them to prevent his extradition to his

native country. He insisted that he “had always fought for a

democratic European choice” for his country and had put forth the

ambitious idea of chairmanship in the OSCE for that purpose. But

now Kazakhstan was “rapidly turning into a monarchic and de facto

police state”, the martyr for democracy warned.

As the November session of the OSCE Ministerial Council in

Madrid was getting closer, one more intrigue – namely, whether or

not the Austrians would hand over Nazarbayev’s former son-in-law –

added to the guesswork about the prospects for Kazakhstan’s

chairmanship bid. Aliev defended himself in every possible way,

including through blackmail: he threatened that he might provide

evidence on Kazakhgate.

Kazakhstan’s State Secretary Kanat Saudabayev, a former

ambassador to the U.S., paid an extremely important visit to

Washington. Astana reported that the U.S. had expressed interests

toward “a further build-up of bilateral cooperation with Kazakhstan

in the energy sector and ramification of export routes for Kazakh

energy resources.” The announcement was intended to serve as a

signal that Washington did not plan to jeopardize its interests in

Kazakhstan by vetoing the country’s chairmanship in the OSCE.

Foreign Minister Marat Tazhin sent a letter on November 20, 2007

to his Spanish counterpart Miguel Moratinos, the OSCE’s

Chairman-in-Office, a week before the session of the Ministerial

Council. It said that “Kazakhstan reiterates its firm commitments

to the fundamental principles of the OSCE.” Tazhin wrote that his

country “stands for the development of all three OSCE

dimensions without diminishing the role and importance of any of

them. […] We must continue developing its human component in

order to strengthen democracy in all participating states.” Tazhin

reiterated that Kazakhstan “will continue the reforms that were

launched in our country in 2007. They specifically encompass such

spheres as the improvement of legal practices and the law on

election, mass media, political parties […].” The contents

of the letter and the very fact that it had been sent remained

confidential until the end of the Madrid meeting on November 30,

when it appeared on the OSCE’s official website.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov did not know anything

about Tazhin’s letter either when he sharply criticized the OSCE

for continuing “to remain on the sidelines of the main

developments” in the world. He unambiguously defended “our friends

from Kazakhstan” against attempts to force them “to somehow

additionally prove their ‘suitability,’ unlike all the others who

have so far been approved without any problems for the role of

‘taking the helm’ of the OSCE.”

Unaware of the fact that the “Kazakh friends” had almost fully

proved their “suitability” by then, Lavrov insisted on the adoption

of new rules for ODIHR activity. Russia’s closest allies in the

CIS, including Kazakhstan, had submitted a draft decision to the

Ministerial Council on the adoption of “basic principles for the

organization of ODIHR observation of national elections,” Lavrov

said, urging others to “carefully study” a draft OSCE charter

prepared by Russia’s allies.

Moscow was ready for an unconditional defense of Kazakhstan’s

chairmanship bid for 2009 up to the blocking of the election of

chairmen for 2010 and 2011. This meant that the organization would

find itself without the troika of leaders as of the beginning of

2008 when Finland got the rotating chairmanship.

However, it was unnecessary to “plug the porthole with one’s own

body,” as the Russians put it. This became clear when Marat Tazhin

took the floor. He promised that his country would “duly take into

account” the OSCE’s recommendations “while implementing the program

of democratic reforms;” in “working on the reform of Kazakhstan’s

election legislation;” in work on media legislation; and in

implementing “the ODIHR recommendations in the area of elections

and legislation concerning political parties.” “We consider the

human dimension to be one of the most important directions of the

OSCE activity,” Tazhin said, thus disproving the Russian thesis

that the organization had over-focused on precisely this area.

Then he totally puzzled Moscow by saying that “as a potential

Chairman” Kazakhstan “is committed to preserve ODIHR and its

existing mandate and will not support any future efforts to weaken

them.” Also, it “will not be party to any proposals that are

problematic for ODIHR and its mandate in the future.”

The diplomatic efficiency of Astana and its Western partners

scourged the pathos of Lavrov’s report at the session, and all the

draft documents he had proposed were rejected in Madrid. The

situation did not leave Lavrov any room to maneuver and a

compromise was reached in the course of his talks with U.S.

Assistant Secretary of State Nicholas Burns just two hours before

the end of the summit: Kazakhstan would get the OSCE chairmanship

in 2010, a year later than initially planned, while Greece would

precede it in 2009 and Lithuania would follow it in 2011.

It is noteworthy that, according to information the author

received from diplomatic sources at OSCE headquarters, the

postponement of Kazakhstan’s term to 2011 turned out to be

unacceptable “for a well-known group of countries.” They would not

like to see a country, on which Moscow could exert substantial

influence, standing at the helm of the organization in the year

preceding the presidential election in Russia.

WITHOUT ADDITIONAL OBLIGATIONS

The Kazakhs perceived the victory in Madrid as the recognition

of achievements made by the country and, primarily, by its

president. “Nursultan Nazarbayev’s charismatic figure and his

activity are by far the biggest attractive assets of the Kazakh

bid,” Russian expert Yuri Solozobov claimed in summing up this

position.

Strange as though it might seem, Akezhan Kazhegeldin, Kazakh

prime minister from 1994-1997 and who has been living in exile in

the West for almost ten years, expresses a similar position.

Kazhegeldin, who held a range of consultations with leading

European politicians at the end of 2007 and the beginning of 2008,

is confident that Nazarbayev’s figure, as well as the fully mature

Kazakh elite and population, has put the country ahead of other

Central Asian states in terms of readiness for sweeping democratic

reforms along the evolutionary path, ruling out dangerous

revolutionary shake-ups.

However, it turned out this spring that Kazakhstan had not taken

a single step toward reforms, which Tazhin had promised in Madrid,

over six months. Western European OSCE member-states supported a

proposal to organize the monitoring of Kazakhstan’s preparations

for assuming chairmanship of the organization.

As for President Nazarbayev’s willingness for reforms, a

statement he made during an interview with Reuters in March 2008

offers a bright testimony. “We have been elected as a full-fledged

member of the OSCE and we do not assume any additional

obligations,” he said. Subsequently, the phrase was mysteriously

cut out of the Reuters newswire and only remained in the version

provided by Kazakhstan’s Habar news agency. There are grounds to

believe it was cut out at the mutual consent of the sides so as to

rescue Astana’s Western partners from a rather awkward situation,

since they regard the Madrid decision as overtures made to

Kazakhstan in an expectation that it will fulfill its promises.

Of what Nazarbayev said, only the ending of his phrase became

known: “I would like to create a democracy like in America, but

where can I find enough Americans for that in Kazakhstan?”

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Kazakh-language website was

blocked in Kazakhstan in early May and access to it was closed for

a month. The government did not issue any answers to numerous

inquiries from the radio’s executives. The site was unblocked only

after interference on the part of the OSCE Representative on

Freedom of the Media, Miklos Haraszti, who sent a letter to Foreign

Minister Tazhin expressing the hope that “the state Internet

service providers were informed by your government that

interference in providing service would violate Kazakhstan’s press

freedom commitments.”

The foreign ministers of five countries – Spain, Finland and

Greece as the current troika of the OSCE, as well as Kazakhstan and

Lithuania that will take the helm at the organization in 2010 and

2011 respectively – met in Helsinki at the initiative of Finland,

the current chairman, in early June 2008. This event did not have

any precedents in the history of the OSCE and it was necessitated

by a growing concern in the West over the absence of democratic

reforms that Astana had promised. This time, however, Marat Tazhin

did not make any promises similar to the ones he had made in

Madrid. He only said that “the interests of all OSCE member-states,

their correlation with the OSCE’s general agenda and relationship

to the priorities set forth during previous chairmanships will be

taken into account as Kazakhstan designs priorities for its

chairmanship.”

It was quite apparent that Kazakh officials came to the

conclusion that no one could take the right to leadership away from

their country, even more so because the OSCE does not have a

procedure for this.

On the other hand, Astana’s actions expose certain logic. The

West will not likely want to spoil relations with Kazakhstan, thus

putting in jeopardy its energy interests, in the first place, and

pushing Kazakhstan into Russia and China’s embrace, in the

second.

***

One will be able to put an end to the story of Astana’s ascent

to the top of European security and cooperation in a year and a

half from now when it officially gets down to its duties as OSCE

chairman. However, there are already a few conclusions that might

be of interest for Russian policies as well.

Like Russia, Kazakhstan faced a choice between fueling its

conflict with the OSCE up to the point of a possible withdrawal

from the organization, and trying to use it to enhance its national

prestige and influence. Preference was given to the latter option,

and Astana seems to be achieving its objectives so far. This

success became possible because the OSCE is a political

organization, first and foremost, and not a human rights watchdog,

and that is why the strategic interests of member-states most

typically outweigh abstract or idealistic considerations there.

This means that countries presenting some interest to the leading

players can efficaciously play on this.

It is also true, though, that Kazakhstan does not want to change

the format of how the OSCE functions, something that Russia does.

Astana will be satisfied with getting the political dividends

proportionate to its geopolitical weight. As for Moscow, it is

pursuing the goal of rewriting the rules of the game, and this is a

far more complicated task per se. But it is equally true that

Russia has incomparably more levers of influence than Kazakhstan

does.

Chairmanship in the OSCE will become an important landmark in

Kazakh foreign policy, and Astana will without a doubt try to use

it to assert itself as a regional leader. For Russia however, this

means problems rather than opportunities. An illustrative signal

was seen in April when Kazakhstan ostentatiously refused to lift

sanctions against Abkhazia and thus put itself in opposition to

Russia. Moscow should obviously put aside hopes that Astana’s term

as OSCE chairman will help it to advance its own positions.