For citation, please use:

Konkov, A.E., 2023. Rules for a Game without Rules. Russia in Global Affairs, 21(3), pp. 114–126. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2023-21-3-114-126

Approved on March 31, 2023, Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept (FPC) is the sixth such document in the modern history of the Russian Federation and the fifth one since the beginning of the century. There are no specific requirements, including time limits, for the FPC, but it is based on the National Security Strategy which has to be adjusted every six years in accordance with the Federal Law “On Strategic Planning in the Russian Federation.” The FPC elaborates foreign-policy provisions of this key strategic document. The current version of the National Security Strategy was approved in early July 2021, after which the need for a new FPC became obvious.

The legal framework for the FPC is traditionally based on the Russian Constitution. Recent constitutional amendments affecting certain principles of the country’s foreign policy have created additional prerequisites for updating the Concept. In particular, the new FPC repeats word for word the fundamental norm laid down in Article 79 of the Constitution: Decisions of interstate bodies adopted on the basis of international treaties interpreted contrary to the Constitution of the Russian Federation are not to be implemented in Russia. In addition, the State Council has been added to the list of agencies that develop and implement the country’s foreign policy as a new constitutional body with foreign-policy powers.

Immediately after publication, public attention was caught by one of the FPC provisions declaring the special position of Russia as a distinctive state-civilization. To a certain extent, this concept stems from a key constitutional novelty: “The Russian Federation, united by a thousand-year-long history, preserving the memory of ancestors who passed on to us ideals and faith in God, as well as continuity in the development of the Russian state, recognizes the historically established state unity.” The same article in the Concept, which determines Russia’s role in the world, contains another atypical characteristic of the country as a European-Pacific power. On the one hand, this expands the established view on the Eurasian nature of the Russian state; on the other hand, it opens up a new dimension of the European-Pacific region with different prospects for building communications and the inevitable opposition to the West’s Indo-Pacific concept.

The FPC specifies certain provisions of the National Security Strategy and some other strategic planning documents, in particular, the Concept of the Humanitarian Policy of the Russian Federation Abroad and the Fundamentals of State Policy for the Preservation and Strengthening of Traditional Russian Spiritual and Moral Values, both approved in 2022.

National Interests and Target-Setting

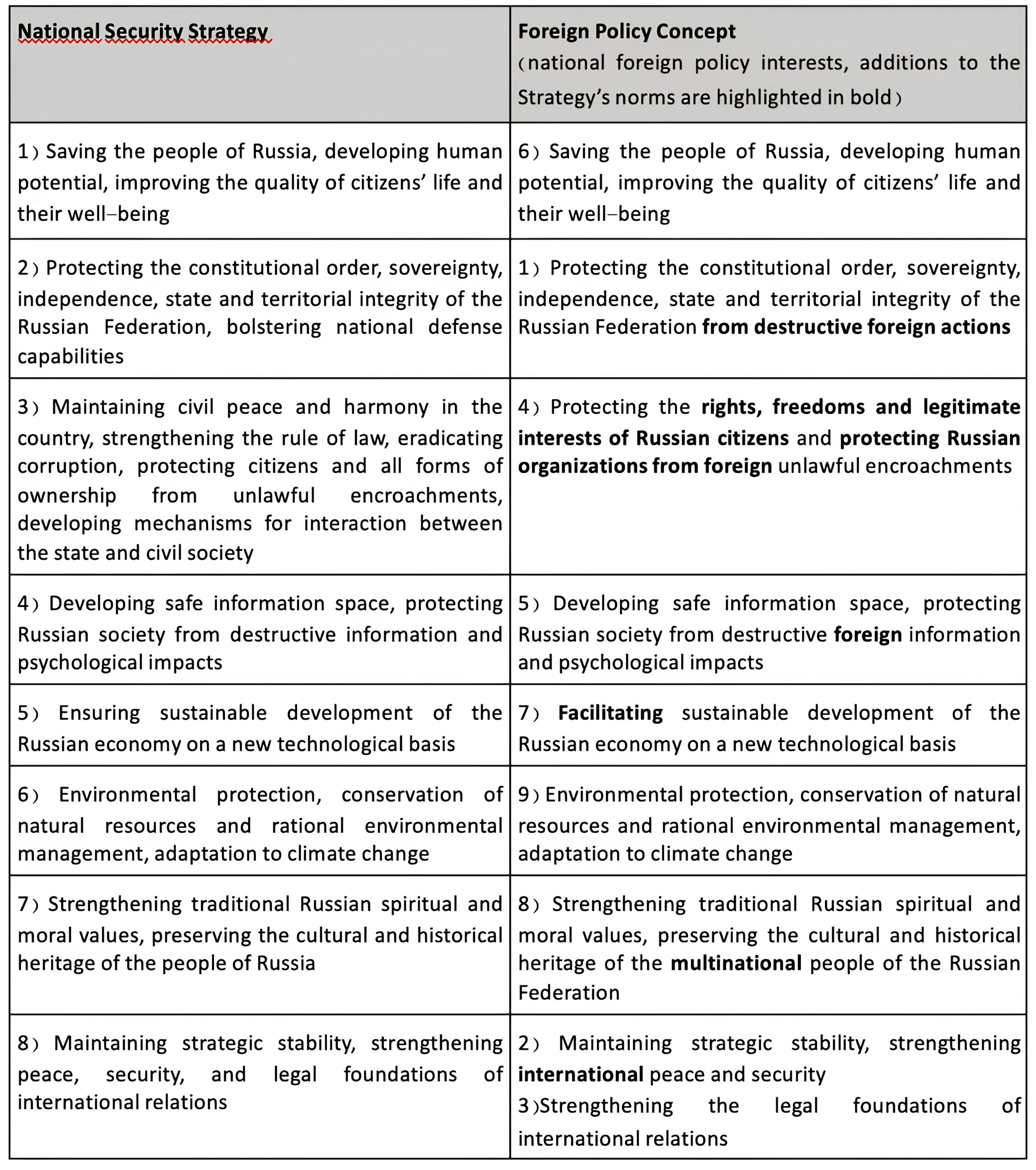

The Concept has been provided with a completely new section that brings together all strategic priorities of the national foreign policy, integrating it into a single vector but at the same time distinguishing it from other areas of state policy—“National Interests of the Russian Federation in the Foreign Policy Sphere, Strategic Goals and Main Tasks of Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation.” The concept of national interests is always closely linked to foreign policy activity. However, since the previous versions of the FPC did not define them, the understanding of Russia’s national interests often became the subject of speculation. Since they were described in general terms, albeit quite clearly, in the National Security Strategy, different sections of the diverse Russian society could interpret them quite freely.

Today, Russia’s national interests are as follows:

Table 1. National interests of the Russian Federation

It is important that Russia has not only drawn up a detailed list of national interests, but has also created a system for their implementation through strategic goal-setting. Nine national interests (detailing and deepening the provisions of the National Security Strategy) are implemented through three strategic goals that integrate and guide Russia’s diplomatic activity:

- Ensuring the security of the Russian Federation and its sovereignty in all spheres, and territorial integrity;

- Creating favorable external conditions for the development of Russia;

- Strengthening the position of the Russian Federation as one of the responsible, influential and independent centers in the modern world.

In turn, these three strategic goals are achieved through 14 main tasks stated in the same section. The remaining sections of the FPC, therefore, provide the tools for solving these tasks—priority areas of foreign policy, its regional dimensions, as well as its development and implementation mechanisms.

The structuring of national interests, and of foreign policy goals and objectives presented in the FPC creates a more coherent and logical framework for the further actions of the country and its representatives in the international arena. One cannot help noticing that the FPC does not mention national development goals, which since 2018 have become a top priority for all government bodies and which should underlie all policy activities regardless of the industry or timelines. However, the fact that the national development goals serve as the basis for the National Security Strategy, pursuant to which the FPC was drafted, allows us to consider the latter as a mechanism for achieving the national development goals outside the country.

Foreign policy priorities have replaced global priorities, which were invariably stated in the previous versions of the FPC. Previously, there were six of them; now there are nine. The following have been added:

- Ensuring Russia’s interests in the oceans, outer space, and airspace.

- Environmental protection and global health (separated from international economic and environmental cooperation).

- Protecting Russian citizens and organizations from illegal foreign encroachments, supporting compatriots living abroad, developing international cooperation in the field of human rights (previously human rights were combined with international humanitarian cooperation).

In addition, the task of “Strengthening international security” has become a priority area called “Strengthening international peace and security.”

Regional foreign policy areas have also been radically restructured. Instead of largely Western-centric priorities stated as “CIS—West—Arctic and Antarctica—Asia-Pacific—Middle East—Latin America and the Caribbean—Africa,” a fundamentally new sequence has been devised:

- Near abroad (perhaps for the first time as an official term)

- Arctic

- Eurasia, China, India

- Asia Pacific

- Islamic world

- Africa

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- Europe

- United States and other Anglo-Saxon states

- Antarctica

Among the declared regional areas, only three countries are named directly: China, India, and the United States. Otherwise, regional areas generalize foreign policy vectors and delve into the bilateral agenda much less than the previous versions of the Concept did.

Content Rearrangement

There is an attempt to take a truly new approach towards planning not just diplomatic work, but international interaction. It includes the abovementioned distinctive identity as a state-civilization, a new look at the geography of regional activities, closer attention to history, and the final postulate calling for increasingly wider involvement of constructively minded public forces in the foreign policy process in order to build a national consensus on foreign policy (different from a more bureaucratic approach to the “consensus nature of foreign policy” taken in the FPC 2016).

Making the first ever attempt to comprehensively and scrupulously determine Russia’s place in the world, the Concept gives its own interpretation of the notion of great powers, conditional, but still urgently needed in actual international relations. The FPC names ten parameters that legitimize not only the status, but also the ambitious priorities of the state-civilization in the world. They provide an insight into how a great power perceives itself:

- The availability of significant resources in all spheres of life,

- The status of a permanent member of the UN Security Council,

- Participation in leading interstate organizations and associations,

- One of the two largest nuclear powers,

- The successor state to the USSR,

- Decisive contribution to the victory in World War II,

- An active role in the creation of a modern system of international relations,

- An active role in the elimination of the world system of colonialism,

- One of the sovereign centers of world development,

- Carrying out the unique mission of maintaining the global balance of power and building a multipolar international system, ensuring conditions for the peaceful and progressive development of humankind on the basis of a unifying and constructive agenda.

On the one hand, it is not customary to try to find added value (including in documents like the Concept) in focused attention on one’s own merits. On the other hand, if one does not praise himself, no one will. Russia has been trying, regularly and at different venues, to explain why it has the right to be among the leaders and why its critical opinion, for example, regarding the “rules-based order,” should be of interest to others. The answer was often situational and sometimes incoherent, unable to withstand the severity of fundamental disagreements with counterparties, whose narrative is well-built.

Another new norm in the Concept eliminates the need for euphemisms and saves time for truly necessary communication. Relations with other countries can be constructive, neutral or unfriendly, depending on the attitude of these countries towards Russia. Among the principles on which a just and sustainable world order should be based, the authors of the Concept name a spiritual and moral landmark for all world religions and secular ethical systems. The previous versions of the Concept mentioned the common (but not single) spiritual and moral potential (FPC 2016) or even the denominator (FPC 2013) of the main world religions.

The concept notes the politicization of various spheres of international cooperation, which is interpreted as negative trends to be opposed by Russian foreign policy. These include, among others, the politicization of the international payment infrastructure, environmental and climate activities, cooperation in the fields of health care, sports, human rights, dialogue, and interstate interaction in various areas in the Asia-Pacific region.

Despite the respectful attitude towards the UN as the main platform for coordinating interests and codifying international law, the FPC emphasizes the strong pressure being exerted on this organization, and for the first time does not mention its reform. All of the latest editions placed emphasis on rational UN restructuring. The new Concept calls for restoring its role as the central coordinating mechanism.

Previously, the Concept usually mentioned the need to reform the OSCE executive bodies in order to boost the role and authority of this largest regional organization. In the current Foreign Policy Concept, Russia no longer speaks of such reform or the OSCE itself, mentioning it just episodically as one of the multilateral formats in the European part of Eurasia.

For the First Time Forthright

The current FPC significantly strengthens the ideological principles of Russian foreign policy. For example, the Concept for the first time uses the term ‘the Russian world’ and notes Russia’s role in its civilizational commonness twice. Despite strong rejection, up to the outright demonization, of the idea of the Russian world by some Western states, Russian foreign policy is firmly set to defend it publicly. For the first time, the Concept mentions Russophobia and says that countering it is a foreign policy priority. Obviously, due to the seeming marginality of the relevant movements, it was not possible to single out such a task before, but new challenges required a direct diplomatic response to attempts to discriminate against everything Russian.

For the first time the FPC mentions color revolutions. Although the main threat of such revolutions was registered in 2000-2010, this phenomenon was not included in the strategic planning framework. Rather, it remained a stable marker for denoting a special class of practices implying interference in the internal affairs of states, usually in the post-Soviet space. After the events of 2014 in Ukraine, the term ‘color revolution’ seemed to have lost its relevance. But as Russia tends to set political directions more straightforwardly and mulls over the nature of the Ukraine crisis, it clearly indicates its intention to suppress attempts to inspire color revolutions and interfere in the internal affairs of its allies and partners. In other words, there will no longer be any recognition of the “free choice” of people if Russia thinks that it is not free or it is not a choice at all.

For the first time, the Concept addresses, and does so quite extensively, the issue of neocolonialism. It notes the active role of Russia in the elimination of the world system of colonialism and the irreversible abolition, currently underway, of the colonial powers’ practice to seize resources of other countries in order to accelerate their own growth. The Concept proclaims the priority of abandoning neo-colonial ambitions by countries, and expresses solidarity with African nations that are seeking to eliminate inequalities aggravated by sophisticated neo-colonial policies.

The idea of consolidating efforts to counter neocolonialism has been actively penetrating the domestic foreign policy discourse in recent months, particularly after President Vladimir Putin’s keynote speech at a Valdai International Club meeting in the fall of 2022, where he emphasized the neocolonial essence of the Western model of globalization.

From Soft to Real Power

Among the main foreign policy tasks, the Concept once again names the need to facilitate an objective perception of Russia abroad. It sets the goal of facilitating and strengthening a positive perception of Russia in the world as part of the efforts to promote international development and humanitarian cooperation. International humanitarian cooperation itself appears not only as a linear type of activity, but has been divided into two areas. One is related to the goal of facilitating a positive perception, strengthening the role of Russia in the international humanitarian space, and developing people’s diplomacy as its separate aspect. The second area is aimed at strengthening the moral, legal and institutional foundations of modern international relations: countering the falsification of history, the spread of neo-Nazism, racial and national exclusivity. Changes in the parliamentary diplomacy goals are also worth noting. All the previous versions of the Concept routinely stated that the Federation Council and the State Duma help improve the effectiveness of parliamentary diplomacy. In the new edition, they facilitate the fulfillment of parliamentary diplomacy tasks.

The absence of any references to soft power in the FPC is a more symbolic novelty. Throughout the 2010s, all key foreign policy documents named it as one of the foreign policy components and permeated domestic political rhetoric to indicate that the country was willing to position itself in the world more effectively. Russia actively encouraged the use of soft power tools, developed relevant institutions and even held fair positions in various ratings and indices. And yet, for many reasons, but most importantly, probably, because the very term ‘soft power’ was alien to Russia, interest in it began to wane at some point.

While giving up soft power, the Concept emphasizes power in its traditional sense. It repeats the need to increase its role stated in the previous editions, but for the first time thoroughly analyzes the emergence of new spheres of hostilities and the hybrid war against Russia, and gives guidelines for a foreign policy response.

For the first time, the Concept allows a possible use of the armed forces by Russia. While reiterating commitment to Article 51 of the UN Charter on self-defense, the FPC lists the following grounds for the use of the armed forces:

- Repelling and preventing an attack on Russia and/or its allies,

- Crisis management,

- Maintaining (restoring) peace in accordance with the decision of the UN Security Council, other collective security bodies with the participation of Russia in their area of responsibility,

- Protecting its citizens abroad,

- Combating international terrorism and piracy.

The Concept emphasizes that in relation to the West, where the majority of unfriendly states are located, Russia has no hostile intentions, it does not isolate itself from the West and does not consider itself its enemy. It simply expresses its attitude in response to the way the West treats Russia. Reciprocity becomes not so much part of politics as such, but a way to realize the spiritual and moral tit-for-tat principle proposed as the basis of a multipolar world. Reciprocity is a continuation of genuine sovereignty, where there is always room for the goodwill of an independent player who is not worried over the obstacles put up on his way and leaves the door open for renewed relations, but at the same time where there is room for a forceful response if others do not want to act amicably.

A New Palette for Contour Maps

Regional foreign policy areas cover ten regions listed according to their priority. For the first time, the minimum number of states is named directly. There are 18 of them in the text, and in this case it is no longer correct to speak of priority because they belong to different regions:

- Belarus

- Abkhazia

- South Ossetia

- People’s Republic of China

- Republic of India

- Mongolia (mentioned within the framework of the Russia-Mongolia-China economic corridor)

- Afghanistan

- Iran

- Syria

- Turkey

- Saudi Arabia

- Egypt

- Israel

- Brazil

- Cuba

- Nicaragua

- Venezuela

- USA

For the first time, the European Union does not appear among the regional priorities, it is mentioned only once, along with NATO and the Council of Europe in the context of unfriendly European states. The European region itself (this is exactly how it is referred to) is predictably considered a foreign policy area second from last and through the lens of individual European countries. Relations with it are conditioned on “the understanding by European states that there is no alternative to peaceful coexistence and mutually beneficial and equal cooperation with Russia, a higher level of their foreign policy independence, and a transition to a policy of good neighborliness.”

For the first time, the FPC introduces the notion of Anglo-Saxon states listed as “and others” in the context of interaction with the United States, with which they make up the penultimate regional area. As far as the United States is concerned, the Concept describes relations with it as “combined,” meaning that the U.S. is one of the influential sovereign centers and at the same time “the main inspirer, organizer and executor of aggressive anti-Russian policy.”

For the first time, Africa appears in the Concept not just as an independent area of Russia’s foreign policy, but as a distinct priority. Russia shows solidarity with the anti-colonial aspirations of African states, and Africa itself is named as a distinctive and influential center of world development. The FPC expresses support for the “African solution to African problems” principle, and in addition to strengthening bilateral relations, the Concept notes a number of multilateral bodies with which Russia intends to deepen cooperation, such as the African Union, the Russia-Africa Partnership Forum, the African Continental Free Trade Area, the African Export-Import Bank, and others.

The Concept traditionally places emphasis on multilateral formats in the context of Latin America and the Caribbean as a separate regional area of Russian foreign policy. In this case, however, on the contrary, the number of priority associations for cooperation has been reduced from seven (in previous versions) to six (the Union of South American Nations has been excluded due to internal disagreements). Among other things, for the first time, the Concept pledges support to Latin American states, experiencing pressure from the U.S. and its allies, in ensuring their sovereignty and independence.

Having It All Immediately

The innovative nature of the Foreign Policy Concept does not negate the contradictory nature of such documents. On the one hand, due to their regulatory nature, they become a direct guide to action for the entire Foreign Service and related agencies in the medium term. On the other hand, since life does not stand still and changes the situation described in the Concept the next minute after its approval, the document, as a rule, cannot reflect the country’s needs and intentions in such a complex and turbulent world. As a state-civilization gets access to the operating space, it acquires a new quality of political-spatial thinking. There is no room for discrete parameters in it: all areas are potentially main ones, and all sorts of paradigms are conditional and transitory.

The purpose of the new Foreign Policy Concept or any other plan amidst permanent chaos is to collect and bring together elements of the previous order, scattered by the past global storms, identify friends and foes, and march towards new cataclysms fully prepared. The ability not only to survive, but also to turn the situation in one’s own favor is a skill that becomes a test for everyone, and the stated foreign policy priorities are intended to help pass this test.