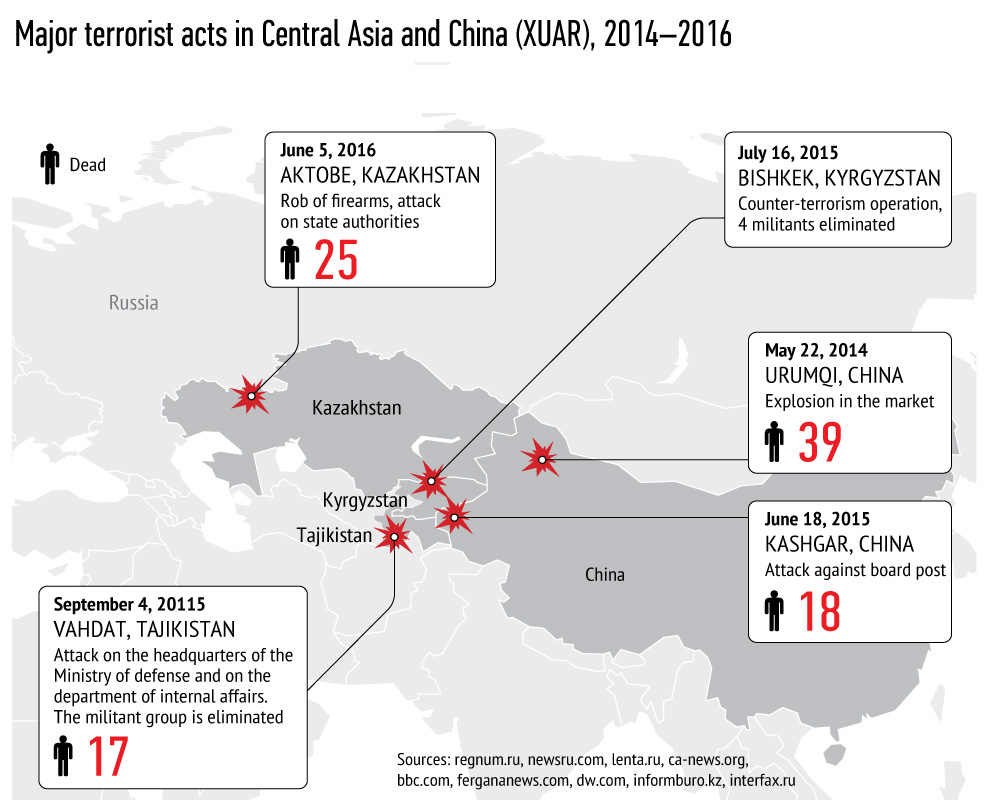

A group of armed militants attacked National Guard weapons depots and barracks in the city of Aktobe in western Kazakhstan on June 5, 2016. Several dozen people, including the attackers, died in the clash. “Siloviki” did not hide their perplexity over what had happened and foreign observers commented that the situation in Kazakhstan – long seen as a model of stability among the southernmost former Soviet republics – might sharply deteriorate.

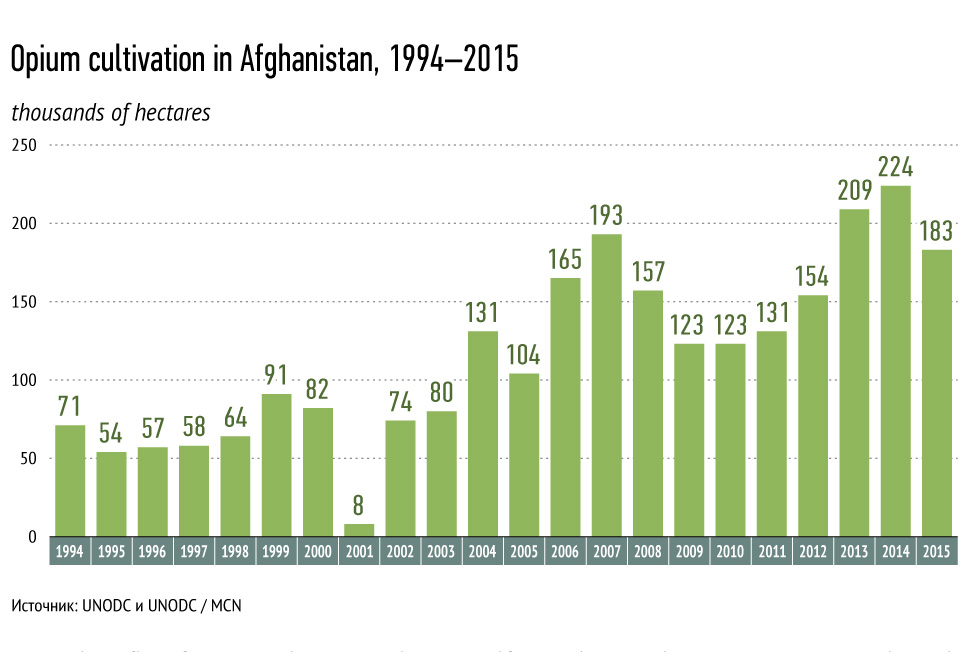

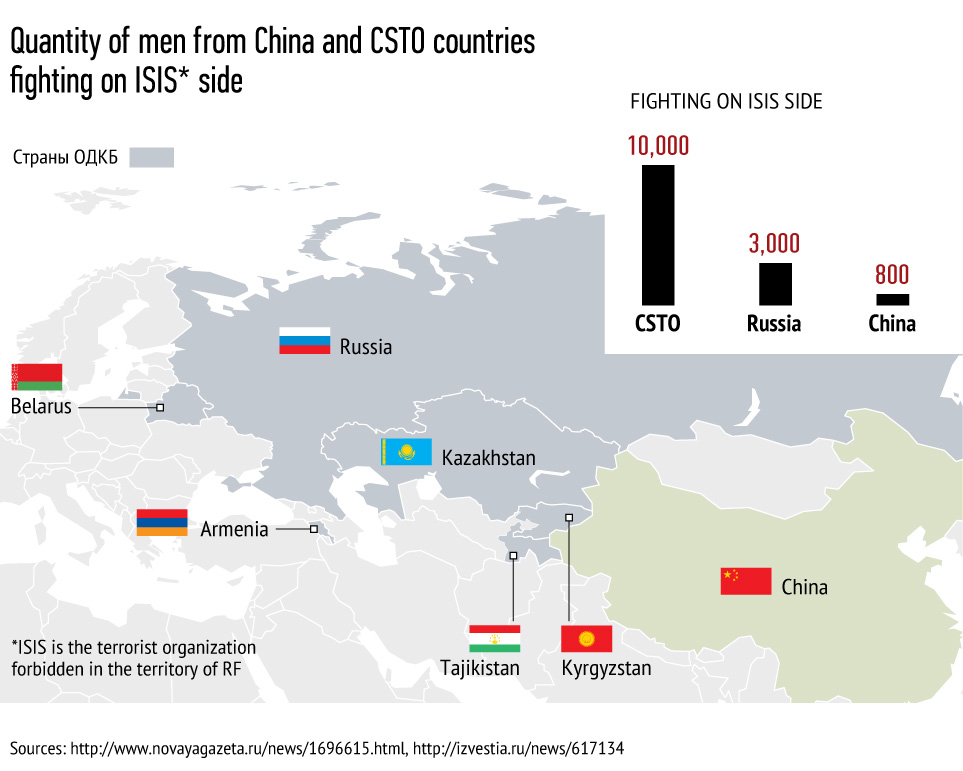

The Central Asian region is increasingly becoming a source of concern for its neighbors and for non-regional powers. The region directly borders one of the most dangerous hotbeds of radicalism today – Afghanistan, whose territory is also home to a signi?cant number of ethnic Tajiks and Uzbeks. It is entirely possible that after Islamic State[1] radicals suffer an inevitable defeat in the Middle East, they will attempt to build a new “caliphate” in Central Asia, especially because it is much safer to fight there than in North Africa, where they are easy targets for gunships in the Mediterranean Sea. Tensions are already mounting in the Central Asian countries nearest Afghanistan and experts have expressed concerns that an increasing number of extremists from Afghanistan and the Middle East are in?ltrating the region.

Despite the signi?cant progress that the “Central Asian Five” (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) have achieved in ensuring stability following the collapse of the Soviet Union, almost every one of those states now faces greater uncertainty over their internal stability. Outside observers point to the lack of a clear method for transferring power when the “patriarchs” in Astana and Tashkent inevitably succumb to natural causes and cease to rule. Valdai Discussion Club experts see an even more dangerous situation developing in Tajikistan. A surge in violence there, as in Aktobe, is by itself undermining the country’s internal stability.

The June SCO summit in Tashkent and the Russian President’s visit to China are good occasions to discuss the need for strengthening multilateral cooperation and ensuring regional security. This particularly concerns the interaction between the region’s two superpowers, China and Russia. Potential instability in Central Eurasia presents a sort of “perfect challenge” for the two countries to engage in a rational game with a positive outcome. A number of objective factors make such cooperation very likely. Following is a close look at each.

First, it is a real possibility that social and political unrest will erupt in the countries in the region. Unlike Ukraine, where a rivalry between outside powers primarily led to that internal con?ict,factors within Central Asia itself contribute to domestic tensions–relatively weak government institutions, poverty, religious radicalism and, finally, the proximity to Afghanistan. The combination of these factors makes the problem especially urgent for both great powers and naturally increases their need to cooperate.

Second, the geographic proximity of the potentially explosive region to the two superpowers plays an important role. Kazakhstan and Central Asia directly border not only the Xinjiang Uygar Autonomous Region – that has more than one million Muslims and poses a particular challenge to China – but also the Urals and Central Siberia that are of critical importance to Russia. Moscow and Beijing understand that if the situation were to deteriorate, they could not simply channel the problem toward the other player and must therefore cooperate on regional issues. What’s more, they could theoretically feel concern over the role played in the region by the European Union, and much more so by the United States. Although unrest in Central Asia would not threaten national security for either, Washington in particular views developments there in the context of geo-strategic cooperation between Moscow and Beijing.

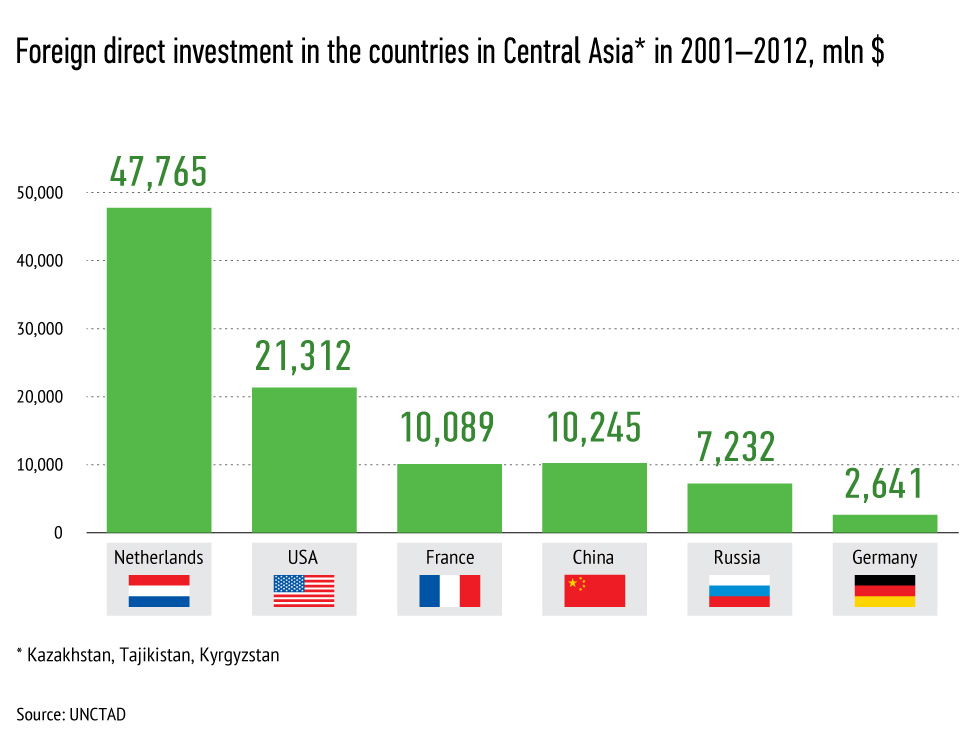

Third, Russia and China are equally interested in removing foreign players from the region, whatever their origin. As just mentioned earlier, developments in Central Eurasia hold a purely political interest for the majority of non-regional players and do not represent a national security risk. Therefore, those countries inevitably seek risky political transformations to the Central Asian states that are generally destabilizing in nature. In addition, the value of the Central Asian states for the U.S., Europe and their economic partners in no way compares with the value of the Persian Gulf monarchies. It is therefore very unlikely that the West would grant the same degree of “immunity” to those states and refrain from wielding its political and economic arsenal against them.

At the same time, some experts contend that Washington is working to establish a direct dialogue with the Chinese authorities – without Russian participation – on the questions of regional security and economic cooperation. It is even possible that such a dialogue has already begun. This indicates that Russia and China need to seek greater transparency concerning their relations with other partners. According to authoritative experts, however, the unpredictability of U.S. policy and its penchant for supporting the so-called “color revolutions” that China so desperately fears might have a limiting effect on such a dialogue. It is worth noting that Russia itself has demonstrated flexibility in responding to revolutionary upheavals in neighboring states – as shown by events in Kyrgyzstan in 2010. One common argument is that Russia is a “waning” force in the region whereas China is a growing force, and that Beijing should therefore cooperate with the United States. All such talk, however, seeks to undermine the trust between Moscow and Beijing – although the paranoid mindset of much of Russia’s mass media presents a greater danger in this regard.

Fourth, Russia and China can offer their neighbors many different formats for interaction to achieve internal stability. Consider the reverse example of European Union efforts to stabilize its periphery. After successfully enlarging the EU in 2004-2007, Brussels launched its “Neighbourhood Policy” of integration, a Euro-centric project aimed at stabilizing its neighbors by encouraging them to adopt EU institutional practices and norms. That is, the arrangement sought to transform those countries and offered them preferential treatment in return for meeting certain criteria. By contrast, Russia and China are not interested in transforming their neighbors, but in stabilizing the political regimes in Central Eurasia and very gradually improving their economic and social conditions over a long period. Russian-Chinese cooperation will have some importance in reducing the negative effects stemming from the inevitable attempts of the countries in the region to balance the influence of the two great powers. In addition, whatever form Russian-Chinese cooperation might take concerning security issues in Central Asia, it should be transparent, multilateral, include the countries of the region and, on a range of issues, Iran.

Thus, objective factors make it almost certain that Russia and China will find a format for cooperating on Central Asia. What’s more, efforts to stabilize the region could bring Russia and China closer in the global context. The reconfiguration of global economic governance seems to be an irreversible process. Large transcontinental associations are forming and the two most formidable Eurasian powers apparently have no alternative but to continue building closer relations. The immediate task is to determine which institutional forms would best make the formation of a “community of interests and values” in Central Eurasia irreversible. The most important practical task before that community and its institutions is to establish internal security through military, law enforcement and economic cooperation and coordination.

There are, however, subjective obstacles as well. Much of the Russian elite and public are not yet convinced that outside powers should take an active role in regional affairs. Instead, they hold by the long-standing notion that, owing to certain historical reasons, Russian should bear exclusive responsibility for regional security. Advocates of this position are concerned that, unlike the fragmented presence of the United States in the region, the Chinese will take a systemic approach. They overlook the fact that Russia has historically become involved in Central Asia to attempt – often successfully – to stem the chaos issuing from the region and to pursue the wealth of South Asia.

Fortunately, those concerns did not hinder the signing of the historic Sino-Russian agreement reached in May 2015 that links Eurasian integration with the Silk Road Economic Belt initiative. The fact that those concerns remain, however, means Beijing should take a cautious approach to building bilateral relations with Central Asian capitals. Traditional regional fears of “Chinese expansionism” are also a factor in this equation, with the anti-Chinese riots in Kazakhstan serving as one recent example. Demonstrators were reacting to amendments to the Land Code permitting the government to sell 1.7 million hectares of agricultural land at auction.

It is also worth recalling that China is known for not getting involved in the internal affairs of its neighbors and for not forming alliances for cooperating on security. Having essentially become one of the world’s great powers, China has adopted a foreign policy typical of a developing country that is constantly striving to protect its sovereignty. The main principles of that policy include non-participation in alliances and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states. Both reflect the thinking of a newly minted power that has only recently achieved full independence and is not yet ready to limit its sovereignty – even for the sake of its own safety and to establish peace in neighboring regions.

In fact, the “new” sovereign China is already 67 years old – a very respectable age. Moreover, the country’s economic capabilities enable it to take greater responsibility for events in the surrounding area. China continues to base its very conservative foreign policy on the conviction that economic growth can solve all problems. This might be the right approach for the Central Asian region, but if so, then China should already be creating new jobs for the disenfranchised youth of Dushanbe and Bishkek. For now, the Silk Road Economic Belt has not developed in any visible way. Over the long term, China will probably have to reassess its conservative approach.

China currently provides limited military assistance in the form of weapons and ammunition to the distressed armed forces of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. It remain unclear, however, if that aid is suf?cient for those countries to effectively respond to the terrorist threat from beyond their borders or, potentially, from within them. What will China do if serious domestic turmoil breaks out in a number of Central Asian countries, and what assurances does Moscow have that Russian troops will not have to cope with that situation alone? Russia, with active assistance from Uzbekistan, has already put down one civil war in Tajikistan. Serious analysts understand that the extensive Russian-Kazakh border – not to mention its proximity to the industrial base in the Urals and the troubled North Caucasus – means that Moscow will have to provide assistance to the Central Asian “Siloviki” in their struggle against the threat of radicalism. In the likely event of a regional crisis, China would quite possibly have to cooperate more actively with Russia, although Moscow, of course, would remain the primary provider of “hard” security in the region. Under such circumstances, flexible forms of intervention such as diplomatic support and assistance for economic recovery would prove most effective.

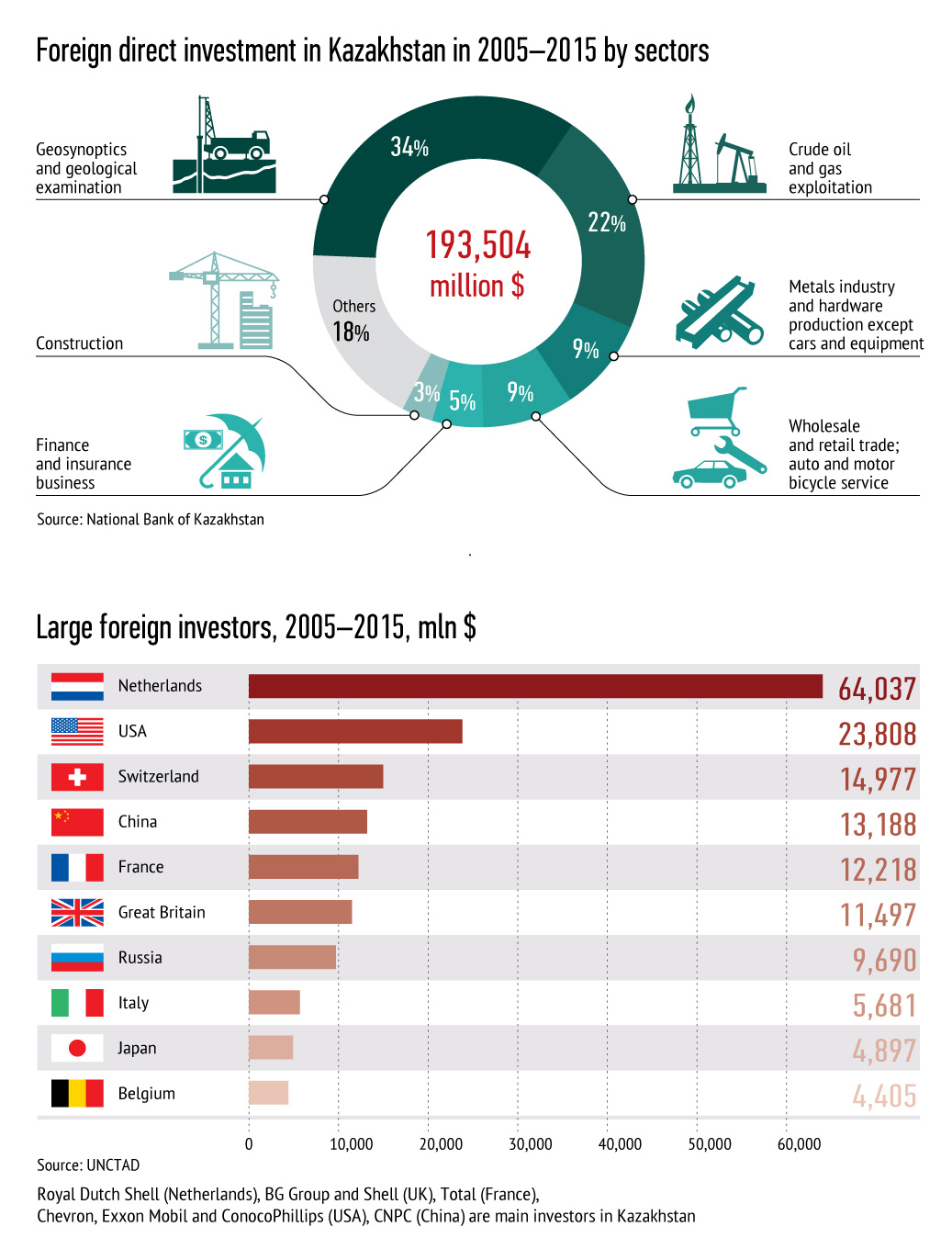

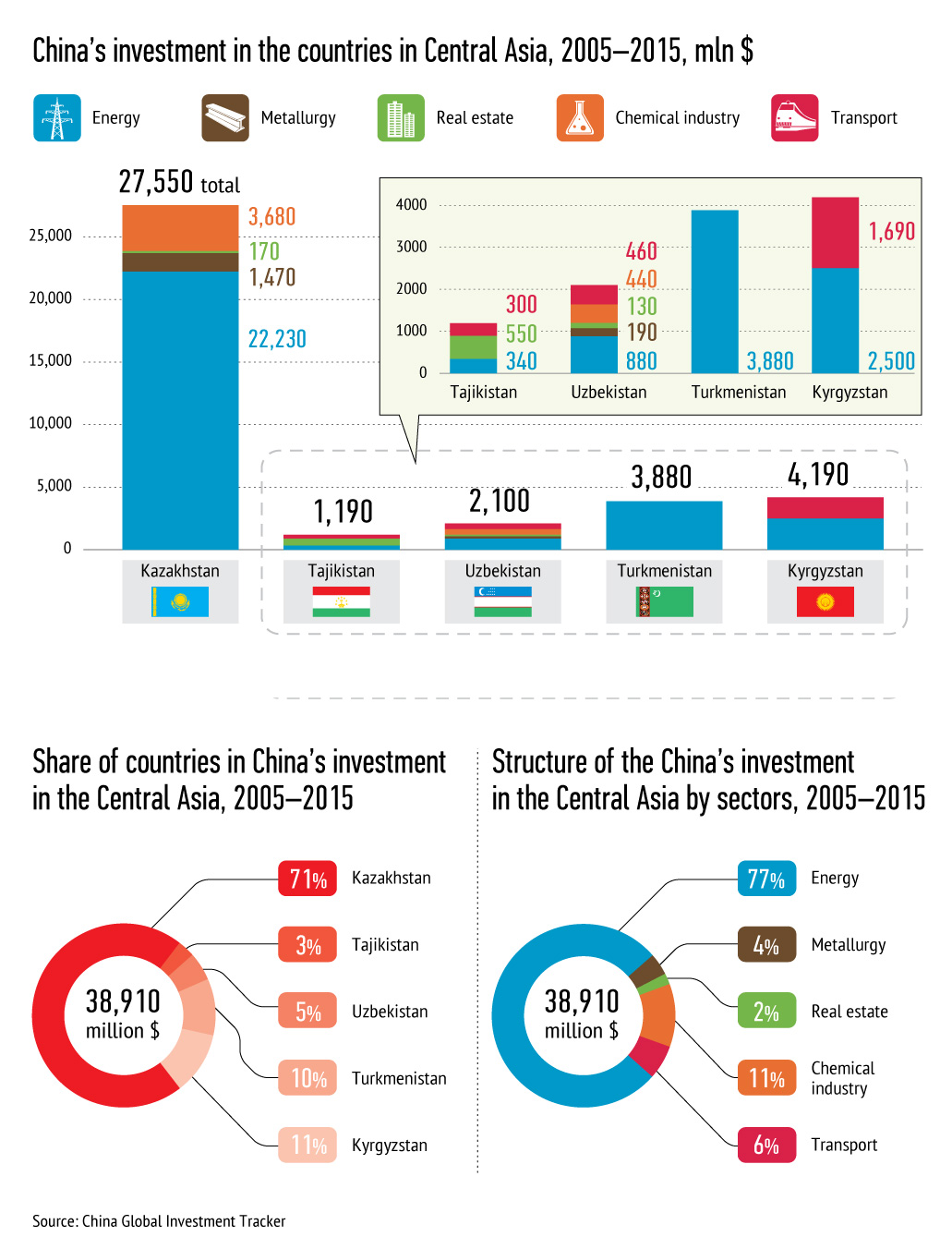

Another important question is whether China’s signi?cant economic presence in the region would affect its willingness to become more actively involved if a crisis arose. According to the World Bank, China has invested approximately $13 billion in Kazakhstan since 2001 – approximately four times less than the $64 billion the Netherlands has invested, and almost two times less than the $23 billion from the United States. China, however, is the primary contributor to the $395.6 million of in Tajikistan accumulated foreign direct investment (FDI) for the period of 2001-2012. China also took the lead for FDI in Kyrgyzstan for the same period, investing $299 million, followed by Russia, with $161 million. Will these relatively hefty investments guarantee that China take an interest in developments in those countries? When Libya collapsed in 2011, for example, China had little trouble writing off the approximately $19 billion it had invested there.

The current prevailing view among the experts is that Moscow and Beijing are both satis?ed with the existing format of relations and are equally uninterested in developing closer ties through a military and political alliance or other formal arrangements. Chinese and Russian analysts, who are clearly on the periphery of those bilateral discussions, only rarely speak directly of the need for an alliance between the two countries. Foreign observers are even more reserved concerning the likelihood of a formal alliance between the two superpowers.

Moreover, the international academic discourse suggests that, given current conditions in the world, major powers such as Russia and China cannot form permanent coalitions for containing states that seek domination. As Jack Levy and William Thompson noted in their brilliant article «Balancing on Land and at Sea» published in 2010, this is especially true if one state is an off-shore power and its potential “balancer” powers are landlocked states. The authors explain that sea-going powers are active beyond the immediate periphery of the landlocked states, and therefore present less of an immediate concern than nearby land-based challenges. One major exception to this theory, however, is the United States, whose forces are very active in the immediate vicinity of Chinese and Russian borders, and in locations that have strategic importance for both countries. To some extent, this makes the U.S. the third great power in the Central Asian/Central Eurasian region.

One major limitation is the fact that, in today’s world, any alliance between major powers that does not include the United States is inevitably anti-U.S. by nature. That would elicit a strong reaction from Washington and its allies that could, in turn, lead to the imbalance, if not the collapse of the entire global economic system – of which China, and to a much lesser extent, Russia are also bene?ciaries. Moscow is also reluctant to link its enormous nuclear missile arsenal to China, whose policies in Southeast and Southern Asia are becoming increasingly assertive.

At the same time, both sides have done much in recent years to eliminate even minor objective factors that could lead to mutual competition. That enables leaders in Moscow and Beijing to announce with con?dence the emergence of a “new form of relations between the great powers” – as the Chinese foreign policy conceptual framework de? nes it. Importantly, this unprecedented rapprochement occurs at a time when both powers have fundamentally different domestic situations than existed immediately after World War II.

China assigned absolute importance to national sovereignty in response to the tragic events its people suffered between 1840 and 1949, and this contributes to the dif?culty Beijing has in forming permanent alliances with other states, even under strong outside pressure. Now, however, the situation has fundamentally changed. China and Russia have no need to fight for their sovereignty or for recognition as full-?edged states. Not only does no one question their sovereignty, but the modern world requires greater coordinated action in responding to challenges and threats.

Global structural changes, however, are perhaps an even more important factor – especially because states have institutionalized some of those changes in recent years. A U.S. led initiative has created a new coalition for managing the global economy that represents a direct challenge to existing institutions and other major players. Those changes might reach such a scale as to undermine the polycentric structure of the international system that appeared following the end of the Cold War. They also threaten the success of efforts that China has made to become an important and respected participant in the system of international relations that has developed over the past 25 years.

A U.S.-led initiative has created a new coalition for managing the global economy that represents a direct challenge to existing institutions and other major players. If, for example, the Trans-Paci?c Partnership (TPP) comes into force, a matrix of tariff and non tariff measures for regulating trade and overall economic activity in the Asia-Paci?c Region will appear. It contains a host of multilateral agreements between participating countries that also re?ects their various existing bilateral agreements.

There is every reason to believe that, even if rati?cation of the agreement proves dif?cult (primarily in the U.S. Congress), the signatory countries will implement its provisions in one form or another anyway. According to Russian expert Igor Makarov, participants not only put tremendous effort into elaborating the TPP and coordinating their various interests, but also into meeting the obvious demand that the leading economies in the region (excluding China) have expressed for the system of relations the TPP propose. There is even a discussion of creating a Trans-Atlantic trade and investment partnership in the Western Hemisphere that would link the economies of the United States, the European Union and a host of other countries.

The scale of these changes is so great that it casts doubt on the possibility of preserving the current polycentric structure of the international system. China is also attempting to become a part of these new arrangements – that apparently began taking shape after the end of the Cold War. However, because the TPP signatories have granted Beijing no formal presence in that project, China’s efforts to become an important and respected member of the international political system that has emerged during the last quarter century might ultimately end in disappointment. For Russia, on the other hand, the new partnership represents a much lesser challenge due to the structure of its exports and the modest scale of its integration into international productions chains. However, if the TPP does move forward, Moscow will have to re?ect those new realities in its foreign policy.

In conclusion, the traditional arguments for and against a hypothetical alliance between Russia and China are based on the assumption that it should serve as a counterweight the U.S. That thinking, however, overlooks the possibility that Moscow and Beijing might build closer relations not “in opposition to” an outside force but “in favor” of dealing with the important challenges they both face – or else simply to establish mutually satisfactory bilateral relations.

The author expresses his appreciation to Dmitry Novikov, Anastasiya Pyatachkova, Andrey Skriba and Ilya Stepanov, Research Fellows of the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies at the National Research University – Higher School of Economics, who made a valuable contribution to this article as well as to Dmitry Suslov, Programmme Director of the Foundation for Development and Support of the Valdai Discussion Club, and Vasily Kashin, and Igor Makarov, Senior Research Fellows of the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies at the National Research University – Higher School of Economics for their advice. The author is grateful for the knowledge and ideas on the researched subject that he distilled from the dialogue with Ivan Safranchuk, the MGIMO Associate Professor; Igor Denisov, the MGIMO Researcher; Erlan Karin, Director of the Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies, and Zhao Huasheng, Fudan University Professor.

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Valdai International Discussion Club