This year

the Russian Internet has celebrated a remarkable anniversary. One

decade ago, in March 1994, the Russian web domain zone .ru was

officially registered. Through all these years Runet (or the

Russian section of the Net) has been dynamically developing,

experiencing both ups and downs. Today, the Internet in Russia is

no longer a mysterious phenomenon that exists beyond the processes

that take place in society, but a full-fledged media and

communicative environment.

BETWEEN

BRAZIL AND SPAIN

According

to the Public Opinion Foundation, the number of Russian users of

the Internet is continuously on the rise and over the past two

years it has doubled. The lengthy experience of computer retrieval

technology and Internet statistics systems shows that the number of

Russian users has been growing by 40 to 50 percent

annually.

According

to a survey carried out by ROMIR, a Russian independent public

opinion research agency, the Internet is presently used by 13.2

million Russians (or 11.7 percent of Russia’s adult population).

According to Rambler’s Top 100, four million people visit Runet on

a daily basis, of which 52 percent live in Russia. Forty-five

percent of Russian users live in Moscow (45 percent of Muscovites

above the age of 16 visit the Internet more than once every three

months); another 10 percent live in St. Petersburg, while the

remaining 45 percent reside in other Russian regions. Moscow, St.

Petersburg, Novosibirsk and several other large cities account for

the greatest number of Internet users due to the large

technological and economic gap between the large cities and the

rest of the country. While in the developing countries, such as

China, Brazil and India, which have made a major contribution to

the growth in the number of Internet users in the world, high

technologies have been proliferating extensively, the

’Internetization’ of Russia has been developing intensively.

According to a Russian market expert, Russia is experiencing what

is known in the West as digital divide: “In the capital and at the

various research centers our self-made programmers are developing

technologies capable of competing in the world market, whereas in

the Russian provinces an automatic milker is still viewed as the

pinnacle of technology.”

In Russia,

the Internet user/non-user ratio is comparable to nations that are

at a level of economic development on a par with Spain or Brazil.

To be more favorably compared with the highly developed Western

nations, Russia needs a more stable economy, as well as a greater

proportion of its population that is financially stable.

Foreign

Policy, an influential U.S. magazine, which annually calculates

(jointly with the A.T. Kearney company) the Globalization Index for

62 countries, has placed Russia only 44th – in the neighborhood of

such countries as Colombia, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and the

Philippines. This is rather indicative of Russia’s present

situation as the level of Internet development (the number of

users, secure sites, etc.) is one of the criteria used to calculate

the index. Basically, this survey shows that IT development in

Russia corresponds to the country’s involvement in the processes of

globalization.

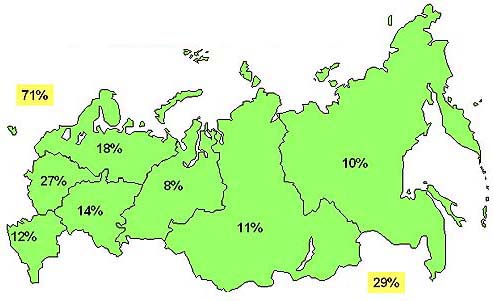

Graph

1. Number of Internet users by regions

INTERNET

JOINS TRADITIONAL MEDIA

Russia is

now experiencing a real breakthrough in the development of IT

technologies. This is due more to changes in public perceptions

than to technological progress. Internet technologies are no longer

viewed as something unusual, mysterious or trendy. The Internet has

become commonplace in Russia, and many Net events are a remarkable

side of society’s life. For example, the presentation of the

National Internet Award in 2003 was broadcast live by the national

TV Channel One. There is a special website

(http://www.linia2003.ru/) where anybody may send questions to

President Vladimir Putin. Over the Internet, people discuss current

events and criticize celebrities and fashion stars. In March 2004,

the Rambler Internet Holding Company was named Russia’s

co-organizer of the Miss Universe beauty contest, and it was

possible for anybody to vote over the Internet for Miss Russia.

Today, the Internet in Russia can serve the needs of broad sections

of the population rather than just the needs of the elite, as was

the situation throughout the 1990s.

Internet

media outlets now rank on a par with the traditional mass media –

newspapers, television and radio. According to the Rambler company,

over 10 percent of Internet users prefer to learn the news from the

Internet. This figure represents one and a half million people,

most of whom are socially active, well-educated and salaried. That

is, these are people who are capable of shaping the events that are

taking place in Russia.

At a

Russian Internet Forum in April, a noted web analyst and one of the

authors of an alternative law on the Internet, Mikhail Yakushev,

said that in 1999 federal regulations made no mention of the

Internet. In 2004, federal legislation mentioned the Internet about

10 times, while in the laws of Russia’s administrative entities the

Internet was mentioned at least 50 times. The federal law On

Communications recognizes access to the Internet as a universal

communications service. This means that not a single citizen of the

Russian Federation can be barred from using the

Internet.

Graph

2. Distribution of Internet users’ interests in February

2004

RUNET, A

UNIQUE PHENOMENON

In

February, at a conference named “Investment in the Russian

Internet,” Andrei Sebrant, editor-in-chief of the Internet

Marketing magazine, described the Russian segment of the World Wide

Web as unique. Unlike other national domain zones, such as those in

Germany, Spain or the UK, the Russian Web was created by people who

were motivated not so much by money as by pure enthusiasm. They

have created resources and services that are in no way inferior –

and in many cases even superior – to those in the West. Users of

the .ru domain have free access to services that their Western

counterparts charge for.

There is

one remarkable incident regarding Runet. Three years ago, Lycos

Europe launched a Russian-language portal to provide Russian users

with their first Internet project of European quality. A year

later, however, Lycos had to close down its operations in Russia:

it failed to win over Russian users who preferred using the local

services of Rambler and Yandex. It appears that Russia,

traditionally viewed as a backward country by the West, has created

Internet products that are capable of successfully competing with

internationally popular resources, such as Yahoo!, Altavista, MSN,

etc.

All major

international Internet projects are in fact products of the

globalization processes and exist within the framework of

multinational corporations. For example, the MSN or Yahoo! sites

are maintained by American and other companies working on the

entire world market, whereas in Russia the development, support and

expansion of Internet services and products is done solely by

domestic companies, even if these companies emerged on Western

money.

The

editor-in-chief of the Internet daily Lenta.ru and one of the

founders of Russia’s web-based mass media, Anton Nosik, says that

“the information content and consumption in Russia by far exceeds

that in many industrialized and well-off nations, because Russians

are very fond of reading and the process of creating Runet’s

information treasury did not involve state officials. Everything

was done on pure enthusiasm, of which the Russian-speaking

intelligentsia all over the globe has more than enough. The Moshkov

Library, Artemy Lebedev’s non-profit Web-design projects, Jokes

from Russia – all these and other projects have been created by

people who make good money in other fields, while the Internet

offers them a way for realizing their creative potential, which is

a function of talent. And Russia has always been rich in

talents.”

Nosik said

Russian Internet projects “are capable of competing on the Western

market, but it would take some will and determination in order for

their creators to tailor them to that market. Two or three

successful examples would be enough to form a tendency. However,

since the market of Internet projects in Russia is not very

transparent, people are not very willing to speak about their

successes.”

Maria

Govorun, editor-in-chief of the authoritative Web-Inform daily,

explains failures of foreign investors in Russia’s Internet by “the

high customer loyalty characteristic of Russian users, which is

largely due to their limited knowledge of Internet infrastructure

and their unwillingness to give up their accustomed Internet

resources.”

In

addition to the high quality of Russian Internet services and the

conservatism of local users, Western Web-designers wishing to enter

the Russian market confront a veritable ’Chinese Wall’ – the

morphology of the Russian language and the bad knowledge of the

English language by Russian users (a non-factor in many developing

countries). The specifics of the Russian language makes it

inconvenient for use with unmodified Western search engines or

antispam programs. Incidentally, Russian hackers, carders and

spammers have played into Russia’s hands. “It appears that they can

be counteracted by Russian specialists only. Therefore, Russian

companies producing antivirus and antispam software (Kaspersky Labs

provides the most illustrative example) are very popular outside

the country,” Govorun says.

LEAVING

THE WAYSIDE

Vladimir

Parfyonov, the dean of the IT and Software Department of the St.

Petersburg Institute of Precision Mechanics and Optics, and a

member of the international organizing committee of the world

software contest, confirmed that St. Petersburg alone hosts about

300 software companies that employ a total of 4,000 people. As of

April 2003, 90 percent of all orders to the tune of U.S. $240

million a year came from the West.

Compare

this with India, which entered the software development business

ten years earlier than Russia, and is the leader in this field – it

attracts orders worth U.S. $6 billion a year from the West. Many

orders are also placed with Irish and Israeli programmers, many of

whom received their education in the Soviet Union.

According

to expert estimates, in 2001 Russia provided U.S. $200 million

worth of offshore programming, whereas in 2003 the figure went up

to reach U.S. $460 million.

Since

demand for IT services in the world continues to grow, offers of

new software vendors are also expanding. Therefore, the outsourcing

market has been growing larger and more diversified. Of the

countries that are relatively new to the outsourcing software

market, special mention should be made of China, Poland and the

Philippines. Although these nations’ share of the world software

market is rather small (the Chinese specialists, whose high

software development skills should not be underestimated, serve

mostly the domestic market), they have a whole range of advantages.

These include the availability of top-notch IT specialists,

competitive prices for their services and, more importantly, strong

governmental support for IT service exports and the industry as a

whole. Evaluating how promising a country is for offshore

programming, Western specialists also use other qualitative

indicators, such as the political situation or cultural

compatibility. However, India’s successful record of approximately

10 years, as well as the successes scored by Ireland, Israel,

Pakistan, China and the Philippines, have shown that the key role

in creating a favorable climate for the development of information

technologies belongs to the government and IT public

associations.

Graph 3.

Qualitative indicators of countries

involved in customized

software development

Source:

Gartner Research

In Russia,

the development of IT has never enjoyed an all-embracing and

coordinated support from the government or industry. Nevertheless,

the Russian software market, its small size notwithstanding, has

shown that it is very dynamic. Thus, there is a trend toward

continuously more growth rates thanks to talented specialists, the

high quality of products and services, relatively low labor costs,

and other factors attracting foreign customers. According to the

RosBusinessConsulting news agency, in 2003, the market of IT

technologies in Russia reached U.S. $5.8 billion, an almost 25

percent growth over 2002.

Government

spending in the IT and communications sector is also growing. The

2003 figures showed that government organizations invested some 13

billion rubles in IT and communications, and this spending is most

likely to be growing further. Regrettably, it is absolutely

impossible to say how much of this money reached the IT domain and

how much of it dispersed as a kickback for agencies and civil

servants. In the IT domain, the practice of receiving kickbacks is

as widespread as in any other industry.

Predictions for the electronic business market are also very

optimistic. In the West, B2B (business-to-business) e-commerce

systems have again become widely used. This section of the market,

oriented toward interaction between companies that are involved in

buying and selling of goods and services, covers trade relations

over the Web. This includes the organization of shipments and

sales, as well as the coordination of contracts and plans. Various

analytical companies tend to believe that in 2004, the total volume

of B2B sales in the world is likely to reach $2,000-7,000 billion.

The National e-Trade Association believes that Russian online

trading, which by the end of 2003 reached a total of $900 million,

will grow by almost 50 percent in 2004. However, currently the

biggest share of the electronic market belongs to the B2C

(business-to-consumer) domain (some $480 million in 2003 and $615

million expected in 2004) rather than B2B. As for B2B, and one

other sector of the market, B2G (business-to-government), their

figures in 2003 were $316 and $141 million, respectively; in 2004

the figures are expected to reach $464 million and $275

million.

It must be

noted that whatever the figures and financial indicators may be for

Russian outsourcing, they are always underestimated. This is

because many of the companies that maintain direct contacts with

their foreign customers defy any tax or statistic registration.

According to various estimates, to the 100 percent of Russia’s

officially registered outsourcing companies one must add 50 to 80

percent of those IT entities which have never been registered; this

latter fact rather significantly changes the overall picture. (Many

unregistered offshore companies continue to be unregistered in

Russia because of their being involved in software support for

Internet porno sites)

Meanwhile,

although Russia has a huge number of high-class specialists, it has

not become a mecca for IT technologies. This is mainly because of

Russia’s prolonged separation from the world economy, the language

barrier, the unreasonable customs and currency exchange policies,

and the lack of governmental support for the software industry. A

serious problem for Runet’s further development is the brain drain

that is flowing from the provinces to the nation’s capital. The

phenomenon of qualified engineers migrating is prompted by

objective factors: compared with Moscow, the country’s periphery is

lacking any promising financial, career and social

opportunities.

Although

Russia has scored several successes, it continues to be on the

outskirts of the software business. This can be witnessed by

statistics that show Russia’s volume of sales of customized

software is less than 10 percent of that in India. The market of

ready-to-use software packages is even less developed; only a few

Russian companies can boast they have won a significant position on

the world IT market. For example, products from the PROMT company

of St. Petersburg, which has operated for over 13 years on the

Russian market of computer-aided translation systems, have been

known outside Russia since 1996. PROMT has been selling its

products in many countries; foreign sales account for about 40

percent of its total turnover.

RUNET:

WHAT NEXT?

According

to many authoritative players on the Russian Internet market, a

time of revolutions and global upheavals within Runet is over.

Rather, the future will be a rather predictable and routine

evolution. The socialization mechanism in society is likely to

gradually change; life will increasingly depend on the World Wide

Web. The Internet may well turn into a space “where people

can arrange their habitat in an

entirely new way,” Ivan Zasursky, head of Rambler’s PR-service,

said, addressing Russia’s Internet Forum. Remarkably, all these

processes will be possible if Russia remains economically stable

and politically wise. The 1998 crisis, for instance, most

negatively affected the development of the domestic Internet

market, as many companies and projects closed, networks and

Internet access services started developing at a much slower

pace.

The last

few years have been marked by rather suspicious attempts by the

government to control the Internet. True, there is a pressing need

to adopt legislation regulating the Internet, but the drafts being

offered by the government to date are more harmful for the

full-fledged existence of the Runet than under its currently

unrestricted condition. Usually, such offers emanate from people or

groups who have only minimal understanding of the Web’s

functioning. A graphic example is an article in the Izvestia daily

(May 16, 2004) written by Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov, entitled On the Darker Side of the Internet,

which in fact is a set of myths and a fuzzy perception of

cyberspace that are so characteristic of man in the street. To

fight against such threats as piracy, violation of copyrights,

porno (which are not the ills of the Internet alone), Mr. Luzhkov

suggested that Web journalists be more responsible, providers be

licensed and, what is more important, each website be registered in

compliance with the Mass Media Law – “so that one would not guess

whether a website, according to the present text of the law,

belongs to ’other mass media’.” But the Web journalists have long

obeyed the general mass media legislation, while the providers must

have at least two licenses (from the Ministry of Communications).

The implementation of the third measure suggested by the Moscow

mayor may result in that all websites that have not been registered

as mass media will be immediately outlawed; regardless, the

dissemination of information contravening Russian law will not be

stopped.

A number

of public figures have also come out with initiatives to legally

regulate the Internet. Thus, Lyudmila Narusova, Federal Council

deputy from the Republic of Tuva, compared the Web to a “smelly

dust hole” and demanded that all websites be licensed.

However,

it’s too early to talk about Runet switching over to the Chinese

model (there, access to the Internet is fully controlled by the

state which is striving to monopolize the market and become the

provider). Apart from objective technical, legislative and

financial difficulties there are negative sentiments in society. It

is due to this combination of factors that the scandalous idea of

implementing a system for operative and retrieval measures (SORM)

have failed. (According to the order of the Ministry of

Communications, all IT operators, including mobile telephone and

the Internet companies, were supposed to install this system at

their own expense and make any information available on a 24/7

basis to the Federal Security Service.) Had this act been

implemented, the secret services would have received practically

unrestricted abilities to eavesdrop on voice communications and

read e-mail messages. Luckily, the Supreme Court of the Russian

Federation ruled that the order ran counter to the

Constitution.

Presently,

the Russian Internet community has consolidated, expanded and

acquired the necessary links and levers to bring pressure on the

authorities. This makes everybody hopeful that any potential

attempts by the government at “making the Internet clearer” would

be opposed by a force powerful enough to shape public

opinion.

the Karabakh Impasse