As international relations go through a period of turbulence, Russia, as many times before, has found itself at a crossroads of key trends that will determine the direction of global development in the future.

There are different opinions, and doubts too, as to whether Russia assesses the international situation and its position in the world soberly enough. This is an echo of never-ending disputes between pro-Western liberals and the advocates of one’s own unique path. There are also people, both inside and outside the country, who believe that Russia is doomed to constantly fall behind and catch up, or adapt to the rules invented by others, and therefore cannot claim a rightful role in international affairs. Let me offer some thoughts on these issues, recalling facts from history and drawing historical parallels.

CONTINUITY OF HISTORY

It has long been noticed that a well thought-out policy cannot be detached from history. This reference to history is all the more justified now that we have celebrated several major dates recently: last year was the 70th anniversary of the victory in World War II; the year before last was the centenary of the First World War; in 2012 we marked the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino and the 400th anniversary of the liberation of Moscow from the Polish invaders. In fact, a closer look at these landmark events clearly testifies to the special role Russia has played in European and world history.

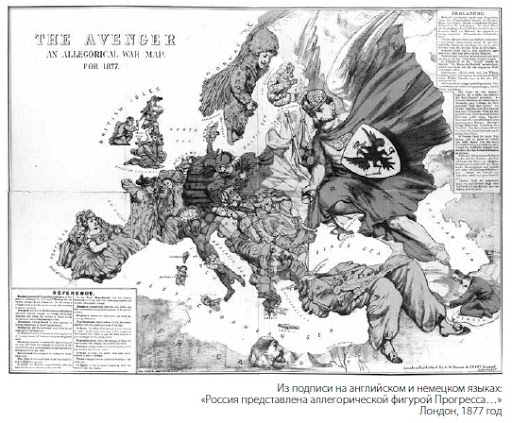

«Russia, represented by an allegorical figure of Progress» London, 1877

Historical facts do not bear out the widespread belief that Russia has always been on the margins of Europe as a political outsider. Let me recall that the baptism of Rus in 988—as a matter of fact, the 1025th anniversary of this event was also celebrated not so long ago—gave a powerful boost to the development of state institutions, social relations and culture, and made Kievan Rus a full member of the European community. At that time, dynastic marriages were the best indicator of a country’s role in the system of international relations. It is a telling fact that three daughters of Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise became the queens of Norway and Denmark, Hungary, and France; his sister married the king of Poland; and his daughter got married to the German emperor.

Numerous studies show that Rus in those days had a high level of cultural and spiritual development, which was probably even higher than that in Western European states. Many respected Western thinkers acknowledge that Rus fit well into the overall European context. And yet, Russian people always had their own cultural matrix and spirituality and never blended entirely with the West. It would be appropriate to recall here the tragic, and largely pivotal, period of the Mongol invasion. Alexander Pushkin wrote: “The barbarians did not dare to leave an enslaved Rus behind their lines and returned to their Eastern steppes. Christian enlightenment was saved by a ravaged and dying Russia.” There is also an alternative view expressed by Lev Gumilyov, who wrote that the Mongol invasion had facilitated the emergence of a new Russian ethnos and that the Great Steppe had given extra momentum to our development.

One way or another, it is clear that that period was extremely important for asserting the independent role of the Russian state in Eurasia. We can recall the policy pursued by Grand Prince Alexander Nevsky who agreed to temporarily submit to the Golden Horde rulers, who were generally tolerant of other religions, in order to defend the right of the Russian people to have their own faith and decide their own destiny despite the European West’s attempts to subjugate Russian lands and deprive them of their own identity. I am convinced that this wise and far-sighted policy is in our genes.

Rus bent but did not break under the pressure of the Mongolian yoke and pulled through that time of hardships to emerge as a united state, which later was viewed both in the East and in the West as a successor to the Byzantine Empire that fell in 1453. A large country stretching practically along the entire eastern perimeter of Europe began to expand to the Urals and Siberia. Already then it became a powerful balancer in pan-European political maneuvers, including the Thirty Years’ War which led to the creation of the Westphalian system of international relations in Europe based, above all, on respect for state sovereignty. Its principles remain important up to date.

And here we are getting to the dilemma the effects of which were felt for several centuries. On the one hand, Muscovy naturally played an ever growing role in European affairs; on the other hand, European countries were wary of the emerging giant in the east and took steps to isolate it as much as possible and keep it away from the most important European processes.

The seeming contradiction between the traditional social order and aspiration for modernization involving the use of the most advanced experience dates back to those days. A rapidly developing state cannot but try to take a leap forward using modern technologies, which however does not mean renunciation of its own “cultural code.” We know many examples of modernization in Oriental societies without having their traditions dismantled. This is all the more true of Russia which essentially is one of the branches of European civilization.

As a matter of fact, demand for modernization based on European achievements became quite evident in Russian society under Tsar Alexis and received a powerful boost during the reign of talented and energetic Peter the Great. Relying on strong measures inside the country and decisive and successful foreign policy, the first Russian emperor managed to put Russia among leading European states in slightly over two decades. Since then Russia could no longer be ignored, and no serious European issue could be solved without it.

It would be wrong to say that everyone was pleased about this. Attempts were repeatedly made throughout the next centuries to push our country back into the pre-Peter the Great times, but to no avail. In the middle of the 18th century, Russia assumed a key role in a big European conflict—the Seven Years’ War. Russian troops made a triumphant entry into Berlin, the capital of reputedly invincible Prussian King Frederick II. Prussia escaped an inevitable defeat only because Russian Empress Elizabeth suddenly died and was succeeded by Peter III who had a strong liking for Frederick the Great. This turn in the history of Germany is still referred to as the Miracle of the House of Brandenburg. Russia’s size, strength and influence increased significantly under Catherine the Great and reached a level where, as then Chancellor Alexander Bezborodko observed, “Not a single cannon in Europe could be fired without our consent.”

Let me quote a renowned researcher of Russian history, Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, the permanent secretary of the French Academy, who said that the Russian Empire was the greatest empire of all times in the totality of all parameters such as its size, ability to administer its territories and longevity. Just like philosopher Nikolai Berdyayev, she believes that Russia’s great historical mission is to be a link between the East and the West.

Over at least the last two centuries all attempts to unite Europe without Russia and against it always led to big tragedies, the consequences of which were overcome with the decisive participation of our country. I mean specifically the Napoleonic wars, after which it was Russia that saved the system of international relations which was based on the balance of forces and mutual respect for national interests, and which excluded total dominance of any one state on the European continent. We remember that Emperor Alexander I took an active part in drafting the decisions of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, which secured the development of the continent without serious armed conflicts for the following forty years.

As a matter of fact, Alexander I’s ideas to some extent foreran the concept of subordination of national interests to common goals, primarily the maintenance of peace and order in Europe. As the Russian emperor put it, “There can be no more English, French, Russian or Austrian policy. There can be only one policy—a common policy that must be accepted by both peoples and sovereigns for common happiness.”

The system created in Vienna was destroyed again by attempts to push Russia to the European sidelines, an idea that possessed Paris during Napoleon III’s reign. In a bid to throw together an anti-Russian alliance, the French monarch, like a hapless chess grandmaster, was ready to sacrifice all the other figures. What happened then? Russia lost the Crimean War of 1853-1856 but managed to overcome its consequences in a short while owing to the consistent and far-sighted policy pursued by Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov. As for Napoleon III, he ended his rule in German captivity, and the nightmare of French-German confrontation hanged over Western Europe for several decades.

Let me recall one more episode from the Crimean War. As is known, the Austrian emperor refused to help Russia which had come to his rescue several years earlier, in 1849, during the Hungarian revolt. Then Austrian Foreign Minister Felix Schwarzenberg famously said: “Europe would be astonished by the extent of Austria’s ingratitude.” On the whole, imbalances in pan-European mechanisms set in motion a series of events that led to the First World War.

I must say that even in those days Russian diplomats put forth ideas that were far ahead of their time. Nowadays people rarely remember the Hague peace conferences convened in 1899 and 1907 at the initiative of Emperor Nicholas II. They were the first attempt to come to consensus on how to reverse the arms race and stop preparations for a devastating war.

The First World War killed and inflicted millions of people and caused the collapse of four empires. It would be appropriate therefore to recall one more jubilee to be celebrated next year, that is, the centenary of the Russian Revolution. There is an urgent need to work out a balanced and unbiased assessment of those events, especially now that many people, particularly in the West, would like to use this occasion for new information attacks on Russia and portray the 1917 Revolution as some barbaric coup that allegedly messed up the entire history of Europe; or still worse, to equate the Soviet regime to Nazism and hold it partly responsible for starting the Second World War.

Needless to say, the 1917 Revolution and the ensuing Civil War were the biggest tragedy for our people. But then, all the other revolutions were equally tragic. However this does not prevent our French colleagues from lauding their upheavals which brought not only the slogans of liberty, equality and fraternity, but also the guillotine and rivers of blood.

There is no denying that the Russian Revolution was a major event that affected world history in many controversial ways. It was some sort of experiment to realize socialist ideas, which were widely spread in Europe at that time and drew support from people a significant number of whom sought such form of social organization that would be based on collective and communal principles.

Serious researchers have no doubt that reforms in the Soviet Union had a significant impact on the establishment of the so-called social welfare state in Western Europe after World War II. European governments introduced unprecedented social security measures inspired by the Soviet Union’s example and aimed at cutting the ground from under the feet of left-wing political forces.

One can say that forty years after the end of the Second World War were an exceptionally good time for the development of Western Europe which was spared the need to make its own crucial decisions and, being under the umbrella of U.S.-Soviet confrontation, enjoyed unique opportunities for peaceful development. This allowed Western European countries to succeed to some extent in converging capitalist and socialist models, which Pitirim Sorokin and other respected thinkers of the 20th century proposed as a preferable form of socioeconomic progress. But for the last couple of decades we have been witnessing the reverse process in Europe and the United States: the middle class is shrinking, social inequality is rising, and controls over big business are disappearing.

No one can deny the role the Soviet Union played in advancing decolonization and asserting such principles in international relations as independent development of states and their right to determine their own future.

I will not dwell on issues concerning Europe’s slide into World War II. Obviously, anti-Russian aspirations of the European elites and their attempts to set Hitler’s military machine against the Soviet Union played a fatal role in this process. And as many times before, the situation created by this appalling catastrophe had to be corrected with the participation of our country which played a key role in determining parameters of the European and world order.

In this context, the notion of “the clash of two totalitarianisms,” which is being actively implanted in the minds of European people, even in school, is groundless and immoral. For all the faults of its system, the Soviet Union never had the goal of destroying entire nations. Recalling Winston Churchill, he was a principled opponent of the Soviet Union his whole life and played a big role in reversing allied relations forged with the Soviet Union during the Second World War towards a new confrontation with our country. Nevertheless, he sincerely admitted that being gracious, i.e. living as one’s conscience demands, was the Russian way of doing things.

If we take an unbiased look at small European states, which previously were part of the Warsaw Pact and now are members of NATO and the EU, it will be obvious that they have not made any transition from subordination to freedom, as Western ideologists like to trumpet, but rather have changed their leader. Russian President Vladimir Putin has recently pointed this out quite aptly. Representatives of these countries also admit in private conversations that they cannot make any significant decision without the approval of Washington or Brussels.

I believe that in the context of the upcoming centenary of the Russian Revolution it is essential for us to realize the continuity of Russian history, which cannot be edited to delete some of its periods, and the importance of combining all the positive trends developed by our people with their historical experience as the basis for moving vigorously forward and asserting our rightful role as one of the leading centers of the modern world, and as a source of values for development, security and stability.

The post-war world order based on the confrontation between the two systems was far from ideal of course but it helped to preserve the foundations of global peace and avoid the worst, namely the temptation to resort to large-scale use of weapons of mass destruction that had happened to be in the hands of politicians, primarily nuclear weapons. The myth about the victory in the Cold War, so popular in the West after the collapse of the Soviet Union, is groundless. In fact, it was the result of our people’s will for change coupled with unlucky circumstances.

PLURAILTY OF MODELS INSTEAD OF BORING UNIFORMITY

It would not be an exaggeration to say that those events triggered tectonic shifts in the global landscape and dramatic changes in world politics. The end of the Cold War and the uncompromising ideological confrontation it engendered opened up unique opportunities for overhauling the European system on the basis of indivisible and equal security and broad cooperation without dividing lines.

There emerged a real chance to finally overcome the division of Europe and realize the dream about a common European home advocated by many European thinkers and politicians, including French President Charles de Gaulle. Our country had fully embraced this chance and put forth numerous proposals and initiatives. It would be logical to lay a new foundation for European security by strengthening the military-political component of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. In his recent interview with the German newspaper Bild, Vladimir Putin quoted German politician Egon Bahr who has similar views.

Unfortunately, our Western partners chose a different path to follow by expanding NATO eastward and moving the geopolitical space under their control closer to Russia’s border. This is the root cause of the systemic problems that afflict Russia’s relations with the United States and Europe. Interestingly, George Kennan, who is considered to be one of the authors of the American policy of containment towards the Soviet Union, at the end of his life described NATO’s enlargement as a tragic mistake.

The fundamental problem associated with this Western course is that it was chartered without due regard for the global context. But the modern globalizing world is characterized by unprecedented interdependence of countries, and today relations between Russia and the European Union cannot be built the same way they were built during the Cold War when they were at the center of world politics. One cannot but take into account ongoing dynamic processes in the Asia-Pacific region, in the Middle and Near East, Africa, and Latin America.

The main sign of the current period is rapid changes in all spheres of international life, which often take unexpected turns. For example, time has proved wrong the “end of history” concept, so popular in the 1990s, proposed by American sociologist and political scientist Francis Fukuyama. It suggested that rapid globalization would signify the ultimate victory of the liberal capitalist model, and that all other models would simply have to adjust as quickly as possible under the guidance of wise Western teachers.

In reality, however, the second round of globalization (the previous one took place before World War I) led to the dispersal of global economic power and, therefore, political influence and to the emergence of new centers of power, primarily in the Asia-Pacific region. The most vivid example is the gigantic leap forward made by China. Its unprecedented economic growth over the past three decades has made it the world’s second largest economy or even first in terms of purchasing power parity. This clearly illustrates the undeniable plurality of development models and excludes the boring uniformity implied by the Western coordinate system.

Consequently, there has been a relative decline in the influence of the so-called “historical West” which became used to seeing itself as the master of mankind’s fate for almost five hundred years. Competition for shaping up the world order in the 21st century has increased. The transition from the Cold War to a new international system turned out to be much longer and more painful than was expected 20-25 years ago.

Against this background, one of the basic issues in international affairs is what form this generally natural competition between leading world powers will ultimately assume. We can see that the United States and its Western alliance are trying to retain dominant position at all costs or, using American terminology, ensure their “global leadership.” All kinds of coercive methods are used to this end from economic sanctions to direct armed interventions; large-scale information warfare tactics are employed; unconstitutional regime change techniques involving “color revolutions” are perfected. But such “democratic” revolutions bring devastation to the target countries. Russia, which went through a period when it encouraged artificial transformations abroad, firmly believes in the preference of evolutionary change which should be made in such a form and at such a speed that would match the traditions of respective societies and their levels of development.

Western propaganda routinely accuses Russia of “revisionism” and purported attempts to destroy the existing international system as if we bombed Yugoslavia in 1999 in violation of the UN Charter and the Helsinki Final Act; and as if Russia ignored international law by invading Iraq in 2003 and distorted UN Security Council resolutions by overthrowing Muammar al-Gaddafi in Libya in 2011. This list can be continued.

All talk of “revisionism” does not stand up to scrutiny and is essentially based on the primitive logic that only Washington can call the tune in international affairs today. This logic suggests that the principle stated by George Orwell years ago that all are equal but some are more equal than others seems to have been adopted at the international level. However, international relations today are too complex a mechanism to be managed from one center. This is vividly borne out by the outcome of American interference: there is essentially no longer state in Libya; Iraq is balancing on the verge of disintegration; and so on.

POOLING EFFORTS FOR SUCCESS

Problems in the modern world can be solved effectively only through serious and fair cooperation between leading states and their associations in the interests of common tasks. Such cooperation should take into account the multivariate nature of the modern world, its cultural and civilizational diversity, and reflect the interests of key components of the international community.

Experience shows that when these principles are applied in practice, it is possible to achieve concrete and tangible results. Suffice it to mention agreements that settle issues concerning the Iranian nuclear program, the elimination of Syria’s chemical weapons, the coordination of conditions for truce in Syria, and the development of key parameters of a global climate agreement. This highlights the need to restore the culture of finding compromises and rely on diplomatic work which can be difficult and even exhausting but which essentially remains the only way to ensure mutually acceptable and peaceful solutions to problems.

These are the approaches we advocate, and they are shared by the majority of countries in the world, including our Chinese partners, other BRICS and SCO countries, our friends in the Eurasian Economic Union, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, and the CIS. In other words, Russia is not fighting against someone but for the resolution of all issues in an equal and mutually respectful manner as the only reliable basis for a long-term improvement of international relations.

We believe our priority task is to pool efforts not against far-fetched but real challenges, the main of which is the terrorist aggression. Extremists from ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra and the like for the first time could take large territories in Syria and Iraq under their control, they are trying to spread their influence to other countries and regions, and they are committing terrorist acts around the world. Underestimating this threat is nothing else but criminal short-sightedness.

The president of Russia has called for a broad front to defeat terrorists militarily. Russia’s Aerospace Forces have made a serious contribution to these efforts. At the same time we have been working vigorously to initiate collective action towards a political settlement of conflicts in this crisis-torn region. But let me stress again, a long-term success can only be achieved if we move towards a partnership of civilizations based on respectful cooperation between different cultures and religions. We believe that universal human solidarity must have a moral basis resting on traditional values which are essentially common for all of the world’s leading religions. I would like to draw your attention to the joint statement made by Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia and Pope Francis, in which they reiterated their support for the family as a natural center of life for individuals and society.

Once again, we are not seeking confrontation with the United States, or the European Union, or NATO. On the contrary, Russia is open to the widest possible cooperation with its Western partners. We continue to believe that the best way to ensure the interests of peoples living in Europe is to form a common economic and humanitarian space stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific so that the just created Eurasian Economic Union could become a connecting link between Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. We are trying to do our best to overcome obstacles on this way, including the implementation of the Minsk accords to settle the Ukraine crisis provoked by the coup in Kiev in February 2014.

Let me quote such an experienced person and politician as Henry Kissinger, who, speaking recently in Moscow, said: “Russia should be perceived as an essential element of any new global equilibrium, not primarily as a threat to the United States… I am here to argue for the possibility of a dialogue that seeks to merge our futures rather than elaborate our conflicts. This requires respect by both sides of the vital values and interest of the other.” Russia supports this approach, and will continue to espouse the principles of law and justice in international affairs.

Russian philosopher Ivan Ilyin, when pondering over the role of Russia in the world as a great power, stressed: “Greatpowerdness is not determined by the size of the territory or the number of inhabitants but by the ability of people and their government to assume the burden of great international tasks and deal with these tasks creatively. A great power is the one which, while asserting its existence and interest…, introduces a creative and accommodating legal idea to the entire community of nations, the entire ‘concert’ of peoples and states.” It is hard to disagree with this.