Belarusians are very close to Russians ethnically and culturally. The overwhelming majority of the Belarusian population speaks Russian at work and at home, and the percentage of Russian speakers has increased noticeably precisely over the years of the country’s independence (from 62.8 percent, according to a 1999 census, to 70.2 percent, according to a census of 2009). Most Belarusians – from 60 to 75 percent – are not only Orthodox Christians but also belong to the Belarusian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The economic and political closeness between Belarus and Russia is formalized institutionally, and no other country in the world is a member of so many organizations in which Russia participates. These are the Union State of Russia and Belarus, the Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and the Common Economic Space between the CIS countries of Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. Ideas of still closer integration – ranging from the introduction of the Russian ruble in Belarus to a merger of the two countries into one full-fledged state – have become less popular over the last decade, yet they regularly appear on the agenda of bilateral relations. No other post-Soviet state has so many qualities that would make it so close to Russia. And yet, despite all these factors, speculations that Belarus is not a sustainable state yet, are not justified.

INDEPENDENCE AS A BOLT OUT OF THE BLUE?

Although there were political forces in Soviet Belarus that consistently advocated independence for the republic, above all the Belarusian Popular Front, their impact on the social and political life in Belarus was much smaller than the influence of similar movements in other Soviet republics, such as Lithuania, Moldova, Georgia and Ukraine. Belarus was not so much the subject as the object of its independence efforts, which were largely caused by events that took place in other regions of the Soviet Union.

On the other hand, the idea of a united country was dying in the minds of many people during the last Soviet years, including members of the Belarusian ruling elite, who had sworn allegiance to the Soviet Union. Perhaps, they nourished some vague hopes that they would have a much higher status in a smaller yet sovereign state than their current status of provincial bureaucracy in a large country.

There were intricate relations – which looked rather like winking at each other – between those who really wanted independence and fought for it, and “nationalists by default” – a large part of society and the ruling elite, which was not against independence in principle. Once the independence was achieved, overt nationalists had no more victories. Moreover, the independence came as a shock to most people in Belarus. Three years later, this shock resulted in a stunning outcome of the first presidential election in independent Belarus. The election was won by a “man from nowhere” – a charismatic member of parliament, Alexander Lukashenko, who promised to protect the people from the horrors of capitalism and, most importantly, to restore the lost unity with “brotherly Russia.”

“A BROOK INTO THE RUSSIAN SEA”

Just a year after the election, Belarus signed agreements on close military and border cooperation with Russia and entered into a customs union with it. In May 1995, the Belarusian president initiated a referendum, in which the majority of people voted for making Russian a second state language and for continuing economic integration with Russia. The following years saw deepening political integration between the two countries – from a community into a Union State. Many people in Russia viewed those developments as a prelude to the two countries’ merger into one state, rather similar to East Germany’s joining West Germany. However, time went on, negotiations continued, Minsk received substantial direct and indirect economic aid from Moscow, yet the countries’ merger never took place.

One had an impression that Lukashenko did not intend to yield the Belarusian sovereignty to the neighboring state and that he instead preferred to enjoy the benefits arising from the endless unification efforts. There could be at least two explanations for this position of Minsk – a political ruse of the Belarusian leader, and different views of the two close yet different nations on their integration. For Russians, who had centuries-old experience of statehood and a by far larger population, integration with Belarus could not be anything else but the latter’s absorption. The point was not even some immanent Russian imperialism – if, for example, Germany and Luxembourg decided to merge, Germans would have the same attitude to the process.

Belarusians had a more complex and ambivalent attitude towards integration. Their aspiration for unity went hand in hand with a strong desire to preserve their identity and not to “dissolve in the Russian sea.” Why did this desire emerge if Belarusians, as was said above, did not – and still do not – distinguish themselves from Russians?

Firstly, Belarusians have always had a parochial consciousness and felt some distance from Russians.

Secondly, the experience of Soviet quasi-statehood in the form of a Union Republic strengthened the feeling of isolation from the Russian and other peoples in the Soviet Union.

And, finally, there had always been – explicitly or implicitly – articulated national aspirations. In 1991, these aspirations in Belarus were weaker than, for example, in Ukraine or the Baltic States. However, forces that were ready to fight and make sacrifices to preserve the Union proved to be even weaker. The majority of the Belarusian population did not – and still does not – share the ethno-cultural version of nationalism, professed in 1989-1991 by people who openly fought for independence. The independence gained in 1991 became possible due to unique circumstances, namely to the processes of disintegration that were taking place throughout the Soviet Union and the tacit coalition between overt nationalists and “nationalists by default.” In subsequent years, overt nationalists were unable to win, but in the struggle against them their opponents generated a different version of nationalism, albeit in a neo-Soviet form.

The unwillingness to “dissolve in the Russian sea” met the interests of the ruling elites who feared losing their status in a unified state, and added to the young state’s experience in building its statehood. The information policy of Minsk was not a major factor here – since Lukashenko came to power and until the end of the century, the mass media, at least those controlled by the state, were not zealous in upholding the values of independence. These values were strengthened by the very fabric of independence: Belarus now had a currency and an army of its own; it pursued an independent policy which in many respects differed from policies of its neighbors, and offered its citizens shorter trajectories of career growth culminating already in Minsk, rather than Moscow. Paraphrasing the first prime minister of independent Italy, Count Camillo Cavour, Belarus began to create Belarusians.

It turned out that it was impossible to give up independence – both politically and psychologically. On the other hand, the integration rhetoric and close relations between Minsk and Moscow made Lukashenko an important figure in Russian politics. He effectively used his contacts with regional leaders of the Russian Federation, both left-wingers and statists, and his access to the Russian media to influence Boris Yeltsin’s Kremlin. Analysts in both Belarus and Russia even began to speak of a real chance for Lukashenko to succeed Yeltsin as president of Russia, or rather a Russia unified with Belarus.

INTEGRATION WARS

The rules of the game changed essentially when Vladimir Putin came to power in Russia. Unlike Yeltsin, he did not have the “Belovezhskaya Pushcha complex” of a destroyer of the Soviet Union. The image of a liberal and pro-Western Moscow, whose ideological confrontation was part of Lukashenko’s political capital, was gone. It was the similarity of the political philosophies of the new boss in the Kremlin and the president of Belarus that caused problems for Minsk. On the other hand, the authoritarianization of public life in Russia denied Lukashenko an ability to influence the Kremlin through Russian public opinion or through elites independent of the Kremlin.

A meeting between Lukashenko and Putin in August 2002 was a major event in relations between the two countries. The Russian leader proposed then that Belarus join the Russian Federation, where all its six regions would be new administrative units of Russia. In the Yeltsin years, Lukashenko repeatedly said that Belarus was ready to go as far in its integration with Russia as Moscow was ready to go. Putin’s Russia demonstrated that it was ready to go all the way. However, Lukashenko categorically rejected the “generous” offer. It should be noted that the reaction of all Belarusian elites showed that over the years of independence and Lukashenko’s rule there had formed a consensus in the country on the value of sovereignty.

Both sides drew conclusions from this crisis. In a keynote speech in early 2003, Lukashenko declared the need for a state ideology. The new policy aimed to substantiate Lukashenko’s authoritarian rule and the values of independence embodied in it. In practical terms, it meant a consistent displacement of the Russian mass media from the media scene of Belarus.

For its part, Moscow, seeing that its partner was not going to proceed with the repeatedly promised unification, switched over to a policy of gradually cutting its economic aid to Belarus. However, this policy met with resolute opposition from Minsk. In addition, it ran counter to the ideological paradigms of Moscow because Lukashenko demonstrated his loyalty to it, at least at the level of rhetoric – something Russia could not expect from the leaders of other post-Soviet states. Also, the Kremlin had obvious ideological sympathies with the anti-Western policy of Minsk. Yet, although the relations between Belarus and the West were reminiscent of the Cold War, Moscow always feared that excessive economic pressure on Minsk or even a mere attempt to change the format of economic relations between the two countries might cause its ally to make a U-turn towards the West.

Russian-Belarusian relations developed in a bitter political and economic struggle. It is worth remembering that the first conflict when the transit of Russian gas was stopped took place not between Russia and Ukraine but between Russia and its closest ally Belarus in February 2004. A much more severe crisis took place in late 2006-early 2007, when Russian gas giant Gazprom doubled the price of natural gas supplied to Belarus and acquired a 50-percent stake in the Belarusian gas pipeline system. In early 2007, Russia imposed an export duty on oil supplied to Belarus, which caused one more conflict, in which the transit of Russian oil via Belarus was stopped for several days.

BELARUS TURNING TOWARDS EUROPE?

It seems that after the oil crisis of early 2007 Lukashenko realized that strong dependence of Belarus on its sole foreign economic and political partner was dangerous, as it could eventually lead to a loss of sovereignty by Belarus and to his personal loss of power. It was then that a “romance” began between Minsk and the European Union.

Russia’s war against Georgia in 2008 sharply increased the Belarusian regime’s value in the eyes of Europe. Lukashenko did not miss his chance: he freed political prisoners, including his former rival in the presidential race Alexander Kazulin, and made it clear that he would not recognize the independence of two breakaway Georgian regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Lukashenko’s calculations worked: the EU suspended visa sanctions against Lukashenko himself and three dozen high-ranking Belarusian officials for six months, and formally invited Minsk to join the Eastern Partnership program. In 2009-2010, Belarus received U.S. $3.5 billion in loans from the International Monetary Fund.

The eagerness for closer relations with Brussels, demonstrated by Minsk, irritated the Kremlin, but it did not mean that Lukashenko came to share liberal values and made a choice in favor of Europe. He had the same motives that Asian post-Soviet autocrats have in their European policies. For them, as for Lukashenko, Europe is a source of investment and a geopolitical counterweight to Russia.

The formation of the new geopolitical configuration was accompanied by a series of conflicts between Minsk and Moscow. These particularly included a “milk war” in the summer of 2009 (a ban on dairy imports from Belarus); an oil war in January 2010 (disputes about oil prices, during which oil supplies to Belarus were suspended for a month); a gas war in the summer of 2010 (when Gazprom substantially cut gas supplies to Belarus over its debt); and finally, a media war in the midst of an election campaign in Belarus, when Russia’s NTV channel broadcast a multi-part documentary entitled “The Godfather” and accusing Lukashenko of corruption and political murders.

A EURASIAN UNION: BACK TO THE PAST?

The December 2010 presidential election in Belarus, questionable in terms of transparency, the crackdown on a protest rally on the night of the election, criminal convictions of dozens of protesters, including five ex-presidential candidates – these developments again threw the relations between Belarus and the West back to the Cold War. Europe and the United States issued travel restrictions for about 200 Belarusian officials, including the president; Washington tightened earlier-imposed economic sanctions against Belarus; and the EU for the first time also imposed economic sanctions against Minsk. In addition, Belarus was hit by a severe financial crisis in 2011. Russia, seeking to take advantage of the situation, began to press for deeper integration (the Common Economic Space agreement, a new stage in the Customs Union, entered into force on January 1, 2012) and for Minsk’s consent to sell some budget revenue-generating assets to Russia.

Economic pragmatism returned together with political and economic metaphysics. Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin announced an ambitious plan to create a Eurasian Union – a close association of post-Soviet countries centered around Russia. Some people saw an ominous specter of the Soviet Union reborn in this idea, but their fears are hardly justified, although it really provides for closer economic and other integration of member-countries and some geopolitical implications that will go beyond mutually advantageous cooperation among the participating countries.

It must be the latter factor that opened new (or rather, old) opportunities for the Belarusian leader – now he could allow his partner to build up symbolic capital in exchange for material benefits. The result was not slow in coming: in later 2011, Russia offered an unprecedentedly low gas price to Minsk and a loan to build a nuclear power plant. However, the deal required more than simple integration loyalty from Minsk – Gazprom acquired 100 percent of Belarusian gas pipeline operator Beltransgaz, in which it had already owned a 50 percent stake.

The Customs Union looks like the first serious integration project (or, according to opponents, the first serious threat to the sovereignty of the participating nations) after numerous imitations in the past. For example, rates of customs duties, which in the Belarus-Russia Union remained different for more than 10 years, were unified in the Customs Union over two years.

But still, it is more likely that the situation has returned to the integration game of the 1990s. This conclusion stems from the previous experience and from changes that have taken place in the public consciousness of Belarus over the independence years.

INDEPENDENCE IN BELARUSIAN CONSCIOUSNESS

In an authoritarian state (and Belarus has been one for quite some time), the foreign policy vector depends on personal preferences of the leader, whereas public opinion has only indirect influence on political decision-making. And yet, at least over a long period of time, aspirations of the people greatly determine the policy. In addition, decisions of an authoritarian leader, which may seem exotic at times, stem from the society that produced him. As Carl Jung said, “A dictator is always led.”

In this regard, of much interest are the results of various public opinion polls, which demonstrate changes in people’s attitudes to various aspects of independence. Below, I will largely quote surveys conducted by the Independent Institute of Social, Economic and Political Studies (IISEPS).

According to a poll held in the spring of 1991 by the All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion (VTsIOM), 69 percent of ethnic Belarusians considered themselves citizens of the Soviet Union, and only 24 percent said they were first of all citizens of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic. The following table shows how the Soviet identity decreased, along with a desire to return it, over the years of independence.

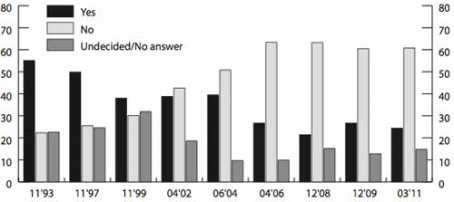

Graph 1. Do you want the Soviet Union to be restored?

Of course, almost 25 percent of all respondents wishing in March 2011 the Soviet Union to be restored is much, yet the percentage of those who do not want this to happen has almost tripled over the independence years and now they make a large majority.

Already in 1996, 64.5 percent of respondents supported the independence of Belarus (34.6 percent were against it). Later, the percentage of independence supporters varied but it never fell below 64 percent: 85.4 percent in 1997, 64 percent in 1999, and 71.8 percent in 2002. In 2009, 65.5 percent admitted that Belarus had benefited from its independence.

Unification with Russia is, perhaps, the only real way to restore the former unity (and to lose sovereignty). As was noted above, the two neighboring nations are very close in very different ways, which is confirmed by public opinion polls. Asked “What makes Belarusians different from Russians?,” about 40 percent of respondents every year say they do not see any difference. As regards closeness of the two peoples, the figures are even more impressive. Asked “Do you feel closer to Russians or Europeans?,” 74.5 percent of people polled in March 2010 said they felt closer to Russians, and only 19.4 percent said they felt closer to Europeans. Finally, when people were asked “Do you regard Russia as abroad?” in 2009, 79.4 (!) percent said no.

GEOPOLITICAL MAGNETS OF BELARUS

However, Belarusians have a more ambivalent attitude towards a state union with Russia.

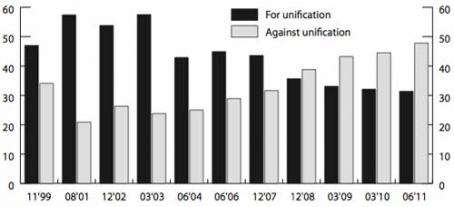

Graph 2. Responses to the Question: “If a referendum on a unification of Belarus and Russia were held today, how would you vote?”, %

Although, as was noted above, about two-thirds of those polled support the sovereignty of Belarus, about 50 percent of respondents until the mid-2000s favored unification with Russia. This suggests that Belarusians are somewhat confused about the notions of independence and integration. When a more concrete question was asked about unification with Russia into a single state, with state symbols of its own, much fewer people supported the idea, compared to those favoring some vague “unification with Russia.”

Most importantly, the number of Belarusians supporting integration with their eastern neighbor has been steadily decreasing with every year. The reasons for this downward trend include a series of trade and media wars between the two countries, people’s habituation to living in an independent state, and, possibly, insufficient attractiveness of the model of the state embodied by present-day Russia.

There is also one more factor, namely the attractive force of one more geopolitical magnet.

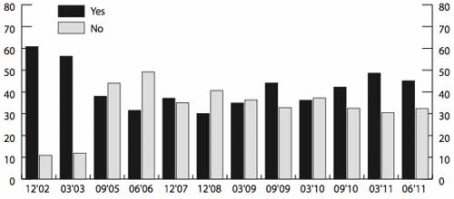

Graph 3. Responses to the Question: “If a referendum were now held in Belarus asking voters whether Belarus should join the European Union, how would you vote?”, %

This table shows an up-and-down fluctuation. In the early 2000s, pro-European aspirations of Belarusians reached their maximum, followed by a sharp decline and a new rise in recent years. Interestingly, the new rise coincided in time with the normalization of relations between Minsk and Brussels. Although the Belarusian authorities’ motives behind this rapprochement were purely pragmatic, the softening of anti-European rhetoric influenced public opinion. On the other hand, this factor indicates the absence of profound anti-European sentiments in the country.

Interestingly, both pro-Russian and pro-European sentiments in Belarus peaked in the early 2000s (2002-2003), when the economic situation in the country sharply deteriorated. Apparently, the crisis produced a desire among many Belarusians to seek help from someone stronger, no matter who. Many of those polled favored both unification with Russia and accession to the EU. However, pragmatism was not the only reason; geopolitical “omnivorousness” of Belarusians has remained to this day.

Looking for identity is a real drama for the whole of Belarusian society and for most Belarusians. This follows from the answers to the question about the possibility of dual integration: in December 2010, opinions on this issue divided: 40.4 percent of respondents said that integration with both Russia and the EU was possible, and 41 percent said it was not. This widespread belief in a geopolitical possibility to “be everywhere” is partly because the prospect of European integration is still a pure abstraction for Belarusians. A dream can go with any reality. The belief in the possibility to “be everywhere” may be naive, but the approximately equal attractive force of the two geopolitical “magnets” is a fact of public consciousness.

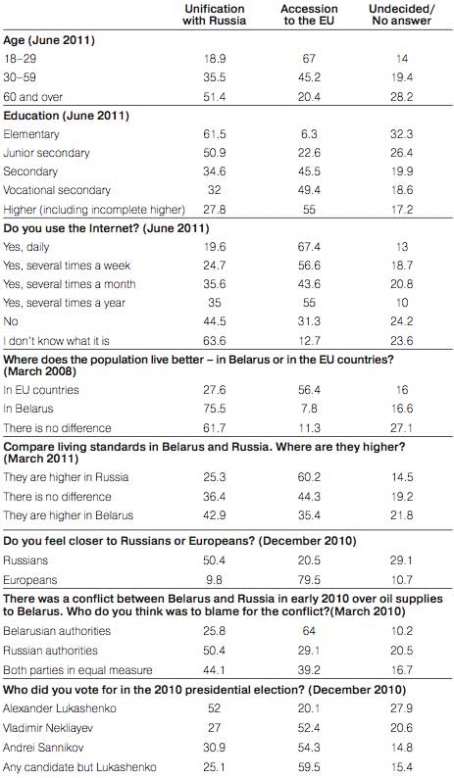

Table 1. Relation between geopolitical choice and socio-demographic characteristics*

What would you choose if you were to choose between unification with Russia and accession to the EU? (June 2011)

* This table should be read across the rows.

It follows from Table 1 that there is actually one society in Belarus rather than two – a “pro-European” and a “pro-Russian” one, where each would have their own groups of young and old people, professors and undereducated people, and so on. There is an obvious correlation of the geopolitical choice with age, education and Internet usage. Young and educated people and frequent Internet users give much more preference to Europe than the average population. Cultural identity turns out to be a no less important factor than comparative assessments of wellbeing.

Table 1 confirms that Russia sometimes acts as a paradoxical internal Belarusian identifier which bears very faint relation to the real country lying east of the Belarusian border. Whereas Europe attracts mostly those who think that life there is better than in Belarus, with Russia things are quite the contrary: the percentage of pro-European Belarusians is the highest among those who believe that living in Russia is more attractive than living in Belarus.

When asked about who was to blame for the January 2010 oil conflict, again the percentage of advocates of the European choice was the highest among those who blamed the Belarusian authorities for the conflict and who admitted that there was reason in what Moscow said. And vice versa, pro-Moscow Belarusians were in a majority among those who blamed Russia for the conflict. We find a similar relation in electoral preferences, as well. Despite the bitter conflicts between Lukashenko and the Kremlin and despite the readiness demonstrated by the main opposition candidates in the 2010 election campaign to take into account Russia’s interests, the geopolitical coordinates of the election remained unchanged – the percentage of supporters of unification with Russia was the highest among supporters of President Lukashenko.

Several years ago, Lukashenko said the famous phrase: “Belarusians are better-quality Russians.” This phrase, certainly offensive to Russians, is the key to the above paradoxes. The Belarusian president and many of his supporters believe that Belarus is an ideal Russia, as it meant to be. It is quite natural that these people are more sensitive about much of what real Russia does than those for whom Belarus is not an ideal Russia and is not Russia at all.

* * *

The coming to power of Alexander Lukashenko was a heavy defeat of political forces that advocate an ethno-cultural version of nation-building. However, the irony of history is that it was Lukashenko – a fighter against nationalism and a politician who promised to restore the Soviet Union – who became, in a sense, the founding father of the modern independent Belarusian state. At the same time, the new Belarusian identity was built according to a civil nation model, in some ways similar to the model of the Soviet people, which has proved viable in a much smaller and an almost mono-ethnic country. However, even within the framework of this quasi-Soviet national ideology, pro-European attitudes in Belarus keep growing. This is a complex process, and Belarus still has a very close cultural and ethnic, let alone economic, affinity with Russia. Belarus largely remains a “divided state,” and there are large groups of people in the country gravitating towards Russia or the West. However, this process has a clear vector, and the repeated rounds of Belarusian-Russian conflicts and reconciliations develop in a spiral, which at each new turn strengthens the realization by Belarusians of the value of their statehood and its independence from Russian statehood.