For citation, please use:

Safranchuk, I.A., Nesmashnyi, A.D., and Komarova, E.S., 2025. Will It Get Worse? Expert Perception of Global Transformation. Russia in Global Affairs, 23(4), pp. 104–112. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2025-23-4-104-112

The international system is undergoing fundamental transformation. Although the world is widely seen as becoming more unpredictable, international experts largely agree that the movement is away from U.S. hegemony and towards a multipolar system with many strong and influential players.

In the late 2010s, U.S. leadership and the order based on U.S. hegemony appeared to be compromised. They were associated with endless wars, the global economic crisis of 2008, a sluggish recovery, and U.S. arrogance. The 2018 Valdai report claimed that the international order was crumbling (Barabanov et al., 2018).

Russia long presented the multipolar alternative as unquestionably positive, as the natural state of the world, featuring harmonious interstate relations, the primacy of international law, and cooperation above confrontation. But in reality, the multipolar world is emerging amid rapidly growing, not decreasing, global tensions. Dozens of countries are increasingly aware that the transition to multipolarity involves numerous difficulties and risks. This does not mean an inevitable return to U.S. hegemony (which has deeply discredited itself, including in the U.S.).

Since 2021, a team of MGIMO and HSE researchers and graduate students has been conducting an annual International Hierarchy Expert Survey (IHES),[1] which is voluntary, anonymous, confidential, online, and in English.[2] More than 200 IR experts in 53 countries took part in the latest (fourth) wave of IHES, from December 2024 to March 2025. Their responses were converted into indices that can be used in research and applied analytics. This article uses IHES data to describe IR experts’ thinking about the world order’s ongoing transformation.

INTERNATIONAL STATUS AND REVISIONISM: IS IT BETTER TO REBEL OR TO OBEY?

Status is the product of how a state is perceived within the system of international relations. It is a composite value underlying a hierarchy, i.e., states’ relative significance and influence. Changes in status show how a general trend, such as the transformation of the world order, affects individual states.

IR experts generally define revisionism as an attempt to change the ‘rules of the game’ and oppose the main guarantor of those ‘rules.’ According to the first survey wave (end of 2021), seven countries were recognized as leading revisionists. These are, first of all, China, Russia, and then (remarkably) the U.S. (A hegemon losing under its own rules may seek to revise them. While most respondents saw the U.S. as the guarantor of an order opposed by revisionists, others saw it as unable to maintain its leadership in the existing system and as therefore seeking to adjust that system.) Well after China, Russia, and the U.S. came Iran, North Korea, Turkey, and India. Although their revisionism index was lower it was still much higher than that of the other countries in the survey.

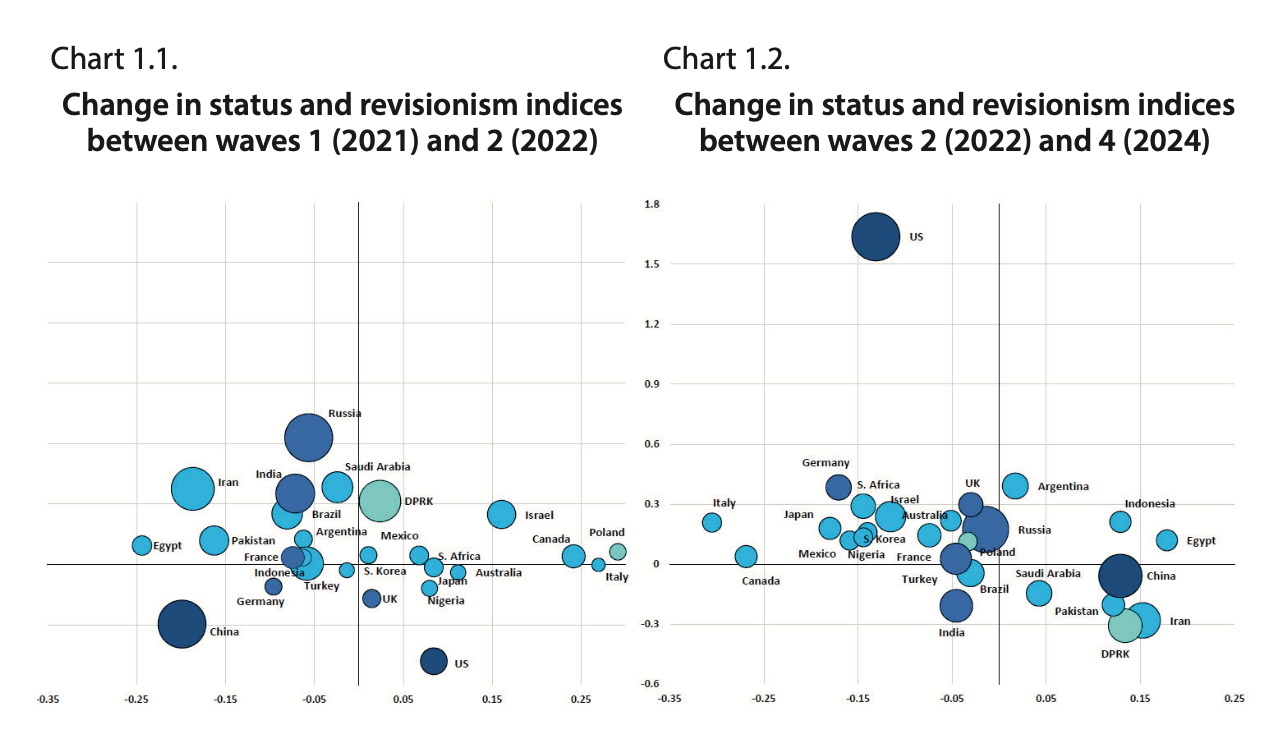

Notes: 1) The horizontal axis shows changes in the status index, the vertical axis reflects changes in the revisionism index. Countries with positive dynamics of both indices (i.e., which became more revisionist and improved their status) appear in the upper right corner of each chart. In the lower right corner are countries with a growing status index and a negative revisionism index. Countries with a rising revisionism index but a falling status index appear in the upper left corner of each chart. In the lower left corner there are countries where both indices show negative dynamics. 2) Circle size indicates revisionism index in the second wave (Chart 1.1) or fourth wave (Chart 1.2). 3) The color of the circles, in order of increasing intensity, indicates small powers, middle powers, great powers, and superpowers.

The turbulent year of 2022 saw significant changes in both status and revisionism evaluations (measured in the second IHES wave (December 2022-March 2023), see Chart 1.1.). Russia’s revisionism index soared (that of Iran, North Korea, Turkey, and India also rose), while the U.S.’s (and China’s) fell. Increased revisionism was also perceived within the Western Hegemonic Bloc (Poland, Israel, Canada, France) and beyond it (Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Egypt, South Africa), but was perceived as having declined for many others in the Bloc (South Korea, Italy, Australia, Britain, Germany). The perceived status of almost all non-Bloc countries—with an increased revisionism—fell. But almost all Bloc countries gained in perceived status, regardless of their revisionism index.

Its defenders enjoyed increased status, while the ‘rebels’ were considered losers with decreased status. Shortly after 2022, as revealed by the survey, experts expected (although not always clearly verbalized) that the U.S. would restore ‘order,’ and that its allies would benefit even more than the U.S. itself. Conversely, Russia—and other non-Western revisionists even more so—would lose out. These observations follow the logic of threat-induced hegemonic consolidation. But no one could say how long it would last, especially given some long-term negative consequences for future hegemony (Nesmashnyi, 2023).

Experts’ perceptions changed significantly in the next two years. Data from the second and fourth (December 2024-March 2025) waves are compared in Chart 1.2. Washington’s perceived revisionism soared to first place, while its perceived status moderately declined. Many U.S. allies—who had been expected to benefit from the ‘restoration of order’—also lost in perceived status, while that of many ‘rebels,’ conversely, improved.

But the main conclusion from Charts 1.1 and 1.2 is the negative correlation between perceived status and revisionism (the harder a country pushes for changing the rules to its own benefit, the more its international position (status) suffers). However, this correlation is weak and has exceptions. Among countries with increased status there are both those with growing and decreasing revisionism. At some moments, pursuing status quo is more likely to help improve one’s international standing (Chart 1.1., 2022), at others (Chart 1.2., 2023-2024), revisionist strategies bear more fruit. In other words, rather than pursuing solely accommodation or seeking revolutionary changes, an optimal strategy would be combining pragmatism with adherence to overarching principles. Arguably, this attitude is particularly strong in the World Majority countries.

TRANSFORMATION OF THE WORLD ORDER: LARGE-SCALE AND DANGEROUS?

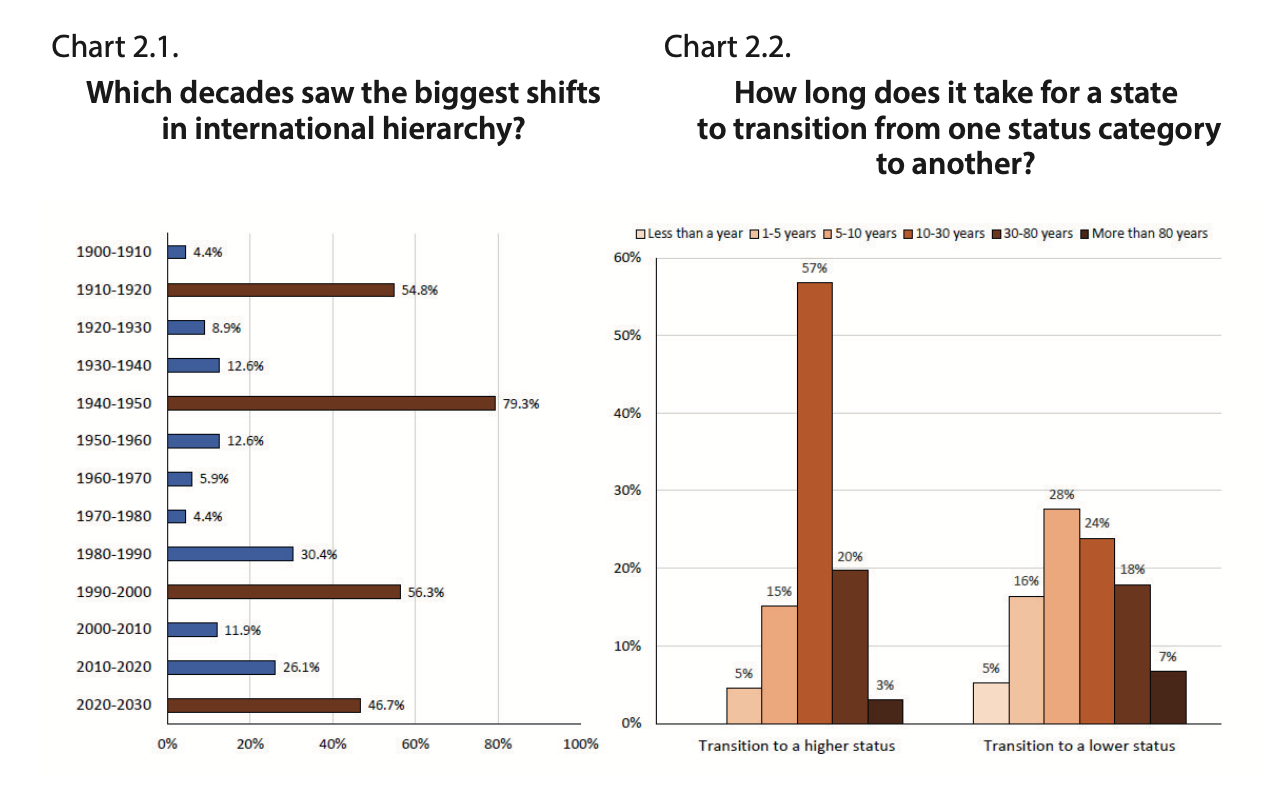

The third wave of the survey (December 2023-March 2024) included the question “Which decades saw the biggest shifts in international hierarchy?” The results (percent of those who chose a certain answer) are presented in Chart 2.1 (respondents could choose multiple options, so the total sum exceeds 100%).

Per Chart 2.1, the biggest changes are placed in the 1940s (World War II), then the 1990s (end of the Cold War), and then the 1910s (World War I). In short, they are associated with someone’s victory or defeat. The current decade falls behind, but its estimates are comparable to those of the post-WWI period.

Respondents were also asked to estimate how long it takes a state to improve or lose its status (Chart 2.2). A clear majority think that 10-30 years are needed for transition to a higher status, far fewer respondents believe that it takes 30-80 years. The least popular option is the view that it is possible to improve one’s international standing within just 5-10 years (no one mentioned one year). Regarding transition to a lower status, experts selected shorter time periods more often. The number of experts who believe that a state’s international standing can worsen quickly (44%, of which 28% chose 5-10 years, and 16% named 1-5 years) almost equals the number of those who think that this is a long process (42%, of which 24% picked 10-30 years, and 18% named 30-80 years).

In sum, the prevailing view is that it takes time to change world hierarchy, but certain states can lose status faster than gain it.

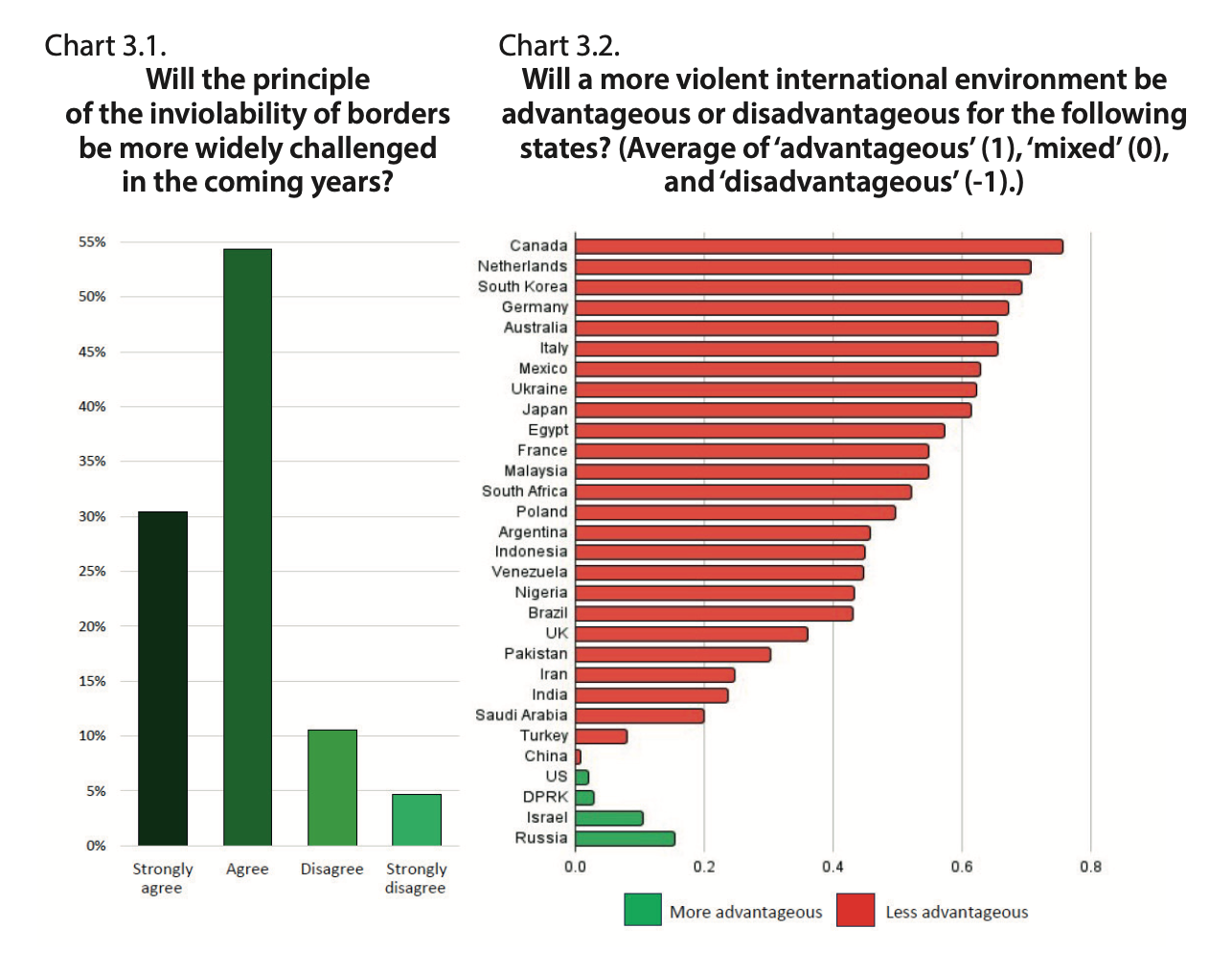

In the fourth wave of the survey (December 2024-March 2025), respondents were asked: “Will the principle of the inviolability of borders be more widely challenged in the coming years?” The vast majority of survey participants thought that it will (Chart 3.1.). Yet most countries are thought likely not to benefit from this (Chart 3.2.). (Some respondents may have been thinking more about states becoming direct beneficiaries or victims of territorial transfers, while others may have more generally considered how states are likely to fare in an international system ostensibly determined more by strength than by norms.)

A more detailed analysis shows that the answer ‘will be less advantageous’ prevailed (and in most cases significantly) for 26 out of 30 states, followed by ‘mixed’ and ‘will be more advantageous’ responses. The answer ‘will be more advantageous’ prevailed for only four countries: Russia, the U.S., North Korea, and Israel. In the case of China, voices ‘more advantageous’ and ‘less advantageous”’ were very close (with the ‘mixed’ option falling just slightly behind them). Turkey and Saudi Arabia, like the majority of listed countries, got the answer ‘will be less advantageous’ more often, but still significantly outvoted most countries in the answer ‘more advantageous.’ So, only Saudi Arabia, Turkey, China, the U.S., North Korea, Israel, and Russia are believed to be relatively ready for a tougher international environment. Among the top 10 states, including those expected to win and those expected to lose less, only China did not resort to a large-scale use of force in recent years. The placement of Russia, Israel and the U.S. on top of this list might reflect the perceived effectiveness of their respective use of force.

In sum, IR experts largely share a negative view on the violability of borders, believing it would be harmful to most states.

* * *

The current transformation of the international system is seen as comparable to those which followed the World Wars and the Cold War. Such a transformation is not expected to be quick. In such a dynamic environment, failure may happen faster than success, and some changes may be disadvantageous to most states. All together, experts are more wary than optimistic regarding change.

The attitudes described above can be reduced to the common ‘risk aversion’ vs. ‘risk tolerance’ dilemma. Experts who have participated in the survey leaned towards the former strategy. This does not mean that the most ambitious countries of the World Majority will end support for the current global transformation. As shown by the low revisionism index for most countries in this group, they would prefer to reduce the speed and depth of undergoing transformations (at least in the short term) in order to reduce risks.

Such attitudes create difficulties for both Russia and the U.S. The World Majority’s rejection of the West’s maximalist anti-Russian position, naturally, benefits Russia. But the Majority’s passive and cautious approach towards the transformation of the world order, on the contrary, plays into the hands of the U.S. It would be best for the World Majority if both Washington and Moscow softened their positions, reducing the intensity of their conflict even if a comprehensive compromise cannot be reached.

The World Majority effectively responds to decisive actions more often with collective opposition than with support, exerting restraint on others’ actions on the international stage.

The international expert community sees both Russia and the U.S. as potentially benefiting from reduced confrontation, since excessive assertiveness in advancing and imposing one’s order adversely affects one’s international standing.

IR experts’ perception of the current global transformation has a contradiction: they expect major change in the international system, but see little preparedness for the associated risks. Historically, transformations have always been associated with someone’s gain and someone’s loss, which determine the new balance of power. But the complexity of transformation impedes calculation of the probabilities of success or failure. Conflicts do more to weaken and endanger their participants than they do to resolve the conflicts between those participants. This new situation is empirically grasped but requires theoretical elaboration.

[1] Over the years, the following people helped conduct surveys and process their results: MGIMO professor I.A. Safranchuk, MGIMO graduate students A.D. Nesmashnyi, V.M. Zhornist, and B.A. Barabash, HSE graduate student D.N. Chernov, MGIMO student E.S. Komarova, HSE students H.Kh. Nabiev and N.A. Svistunov, and HSE research fellow Dylan Royce.

[2] For the survey methodology and indices based on survey results, see: Nesmashnyi, Zhornist and Safranchuk, 2022; Safranchuk, Nesmashnyi and Chernov, 2025. Survey data is available on Harvard Dataverse: Chernov et al., 2025.

_________________________

Barabanov, O., Bordachev, T., Lissovolik, Y., Lukyanov, F., Sushentsov, A., and Timofeev, I., 2018. Living in a Crumbling World. Valdai Club Annual Report, 15 October. Available at: https://valdaiclub.com/a/reports/living-in-a-crumbling-world/ [Accessed 13 August 2025].

Chernov, D., Nesmashnyi, A., Zhornist, V., and Safranchuk, I., 2025. International Hierarchy Expert Survey. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PXVTEY

Nesmashnyi, A.D., Zhornist, V.M., and Safranchuk I.A., 2022. International Hierarchy and Functional Differentiation of States: Results of an Expert Survey. MGIMO Review of International Relations, 15(3), pp. 7-38.

Nesmashnyi, A.D., 2023. European Security Crisis and U.S. Hegemony: Reversing the Decline? Russia in Global Affairs, 21(1), pp. 132-152. Safranchuk, I.A., Nesmashnyi, A.D., and Chernov, D.N., 2025. International Hierarchy Expert Survey: Wave III Report. Russia in Global Affairs, 19 January. Available at: https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/international-hierarchy-report/ [Accessed 13 August 2025].

Safranchuk, I.A., Nesmashnyi, A.D., and Chernov, D.N., 2025. International Hierarchy Expert Survey: Wave III Report. Russia in Global Affairs, 19 January. Available at: https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/international-hierarchy-report/ [Accessed 13 August 2025].