A major task of global diplomacy is settling local war-related international crises. However, the post-Cold War period has witnessed the emergence of some new trends. Instead of taking a neutral stance whenever and wherever possible, and pushing warring parties towards peace, leading Western powers are beginning to act differently. In most trouble spots, a ‘right’ party—the good guys—is chosen that enjoys the political, military, and diplomatic support it needs to achieve a victory over the bad guys. Proceeding from their current interests, more powerful countries often ignore the fact that, as a rule, there is no right or wrong party in domestic conflicts and civil wars; indeed, the responsibility often lies with both sides. Recently, there have been many examples of such a policy, so it might be interesting to look back at how it all began—in Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.

THE PRICE OF DOMESTIC POLICY INDULGENCE

After perestroika removed the confrontation paradigm of the Cold War in foreign policy, Russian President Boris Yeltsin and Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev generally followed in Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev’s footsteps. Russia strove to return to the mainstream of civilization from which it had been rejected after the 1917 October Revolution. Many obstructions disappeared, such as ideological confrontation and the Cold War. Russian cooperation with the United States and Western Europe became a political priority.

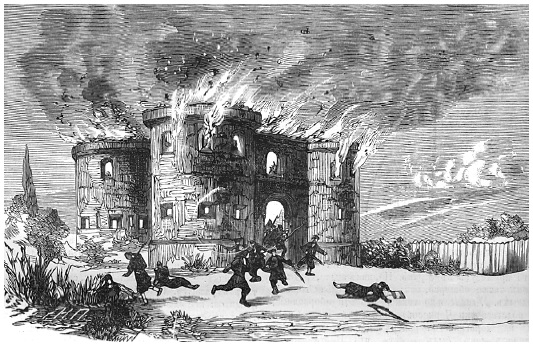

The taking of a Turkish fortress by the Serbs

A. Gatstuk Newspaper, 1876

Arms reduction remained a major issue on the foreign policy agenda and some real steps were taken along these lines. Russia declared that it was the legal successor to the Soviet Union and was recognized in this capacity. Additionally, Russia kept its seat as one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council.

Such a strategy looked fairly reasonable. Yet in practical policies a fundamental mistake was made from the outset: unconditional orientation towards “civilized” countries, above all, the United States, became the cornerstone of Russian foreign policy. However emasculated, Russia could have laid claim to something more than being just the U.S.’s junior partner. However, the factor of internal political struggle intervened.

While Boris Yeltsin secured absolution from the U.S. for tough measures in his domestic policy (for instance, the shelling of Russia’s defiant parliament in October 1993), he had to pay something back in international affairs. Neither the first president George Bush nor Bill Clinton, nor their secretaries of state, were scrupulous in their foreign policies. The crisis in Yugoslavia is a sad confirmation of this.

My first close experience of this dates back to the fall of 1992, when, after an assignment in Italy, I returned to the Foreign Ministry in the capacity of first deputy foreign minister. Soon the events inside and around Yugoslavia took a very nasty turn. The general feeling was that psychological preparations were underway for outside military intervention. At first it was not very clear why the Americans needed all that. Previously, they had preferred to stay aloof from Balkan affairs and for a certain period of time they even opposed the disintegration of Yugoslavia. In December 1991, the U.S. was still reluctant to recognize Croatia. But by the spring of the next year, the U.S. had recognized not only Croatia, but also Slovenia, and—even worse—Bosnia-Herzegovina. Hostilities flared up immediately. Apparently, the U.S. realized that the Balkans was a jackpot: support for the Muslims alone promised huge political gains as compensation for the costs of alliance with Israel. The role of supreme arbiter in the Balkans looked very attractive to Clinton, as the leader of the sole remaining superpower. The U.S. expected that, by pressuring the Serbs, it would be easier to eventually dictate a peace agreement on U.S. terms.

In such a situation, Russia’s task should have been to prevent armed intervention; the more so since the matter at hand was a civil war, which the West eventually admitted. Russia should have pressed for a political settlement as an alternative to the use of force and for an equitable approach to the three warring factions—the Serbs, the Croats, and the Bosnians. In principle, this is precisely the policy that Russia had followed most of the time, but at some key points it had succumbed to U.S. pressure.

The first big mistake was made in May 1992 when Russia voted for a UN Security Council resolution introducing prompt and harsh sanctions against Yugoslavia. When I was still Russian ambassador to Italy, I wrote to Moscow not to rush to impose sanctions against Serbia. I urged to at least first calculate what sanctions would cost us. We could always use Russia’s economic position to explain our reluctance to those who were pressuring us. It might even make sense to ask them what their compensation for our likely losses would be. I insisted that in the Balkans Russia should play its own game, the way Germany did. I wrote that it would be wrong to turn our backs on Serbia, Russia’s traditional ally. Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic and his “dubious exploits” would be forgotten but if Russia betrayed the Serbs, the memory of that act would be imprinted in history. Unfortunately, my cable warning against sanctions was the only one from a Russian ambassador and it never left the Foreign Ministry building to reach the country’s leaders. An anonymous do-gooder later leaked the full text to the Den’ ultra-right nationalist newspaper. In the old days one could have gone to jail for taking such liberties.

Later, Vitaly Churkin, deputy foreign minister who was then responsible for Yugoslav affairs, told me that not a single expert at the Foreign Ministry supported sanctions at the time, but everyone was afraid to protest. The range of sanctions was unprecedentedly broad, yet the Russian government hastily agreed to them. The sanctions and Russia’s stance had an explosive effect on the Serbs. Surely, Russia could have used as an argument the Chinese refusal to implement sanctions against Serbia, as the Chinese government had declared openly that economic measures were not advantageous to it. Until the last moment, Milosevic had been confident that Russia would not leave him in the lurch.

I do realize that in a situation where the Serbs were under severe criticism (and with good reason) from all sides, it was very difficult not to yield to the prevailing sentiment. But Milosevic was not the only one who fanned the flames of the conflict. Croatian President Franjo Tudjman and Bosnian President Alija Izetbegovic did precisely the same. Biased approaches were standard practice in the West. There was one indisputable rule—if the Serbs were to blame, nobody else was. If someone else was to blame, than everybody was responsible. Russia had the resources to play a more diversified game. The country’s prolonged resistance to the use of force was a sure confirmation of that.

The U.S.’s Cyrus Vance and Britain’s David Owen, the co-chairs of the Executive (sometimes referred to as Steering) Committee that the 1992 London Conference on Former Yugoslavia had created, stood firm. UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali and his envoys were opposed to military operations out of fear for their personnel safety. In January 1993, Martti Ahtisaari, the co-chair of the working group for Bosnia-Herzegovina, said publicly that Russia’s efforts had brought political methods, and not the use of force, to the forefront.

I suspect that many in Russia (just as in the U.S.) regarded Milosevic as one of the “Commies” on whom one should clamp down. Our approval of the sanctions, as one politician remarked unofficially, was a way of punishing those “red punks.” Russian foreign policy took the form of party politics, not of a national strategy. On the pretext of discarding ideology, many turned a blind eye to distinctions rooted in geopolitics. The nationalist-minded pseudo-patriots managed to grab the banner of the country’s dignity. Even the most sensible steps were avoided simply because it would be a concession to the old hardliners.

There was a great deal of discord. It is enough to recall the abortive idea (proposed very seriously!) of sending Russian warplanes to U.S. squadrons in order to bypass the Supreme Soviet’s emphatic rejection of air strikes against the Serbs.

“IT’S NOT ANOTHER IRAQ!”

In January 1993, Foreign Minister Kozyrev said that Russia had actually been using a latent veto in the UN Security Council against military intervention for two months. However, soon another attack followed. This time it was the French who proposed using military force to ensure a no-fly zone imposed on Bosnia-Herzegovina. Practically all parties supported them. That measure was to facilitate the enforcement of the Vance-Owen peace plan, in case everybody agreed to join it. The Vance-Owen plan for Bosnia-Herzegovina was drafted in 1993 and had Russian support.

Yuli Vorontsov, Russia’s Special Envoy to the United Nations, sent a cable from New York that the question of applying sanctions against those who might violate the no-fly zone had been reported to Kozyrev (the latter had flown to the U.S. to make preparations for a Yeltsin-Clinton meeting) and that Russia would vote for the French proposal. We were perfectly aware that Kozyrev was inclined to support that resolution from the outset. He wrote to Yeltsin stating that although the resolution was French, it was one of Clinton’s ideas. Kozyrev also reiterated after Bush that the U.S. was prepared to use force to enforce the no-fly zone.

The proposed no-fly zone was a clear move against Serbia. Only the Serbs had planes in the area, and now they were about to be stripped of that advantage. Can one interpret this in any way other than as a step intended to weaken one of the parties in a conflict? The ground forces—in which the Muslims had superiority—were left intact. The Serbs denied any violations; they argued that the UN was closely monitoring all of their actions. But the French told me outright: “It does not matter whether the Serbs violate something or not, public opinion is against them, and we only make allowances for that.” Yet it was not only the Serbs that really mattered. For the first time, outside intervention was about to be legalized as a precedent.

Sergei Lavrov, the then deputy foreign minister in charge of UN affairs, and I knew of the only way to prevent this—by appealing to the president. Out of a feeling of loyalty to Kozyrev, we repeatedly postponed such a move. This tactic paid off: Yeltsin phoned me himself. I still remember his distinctive voice and his peculiar intonation. “Why am I not briefed on fundamental issues, eh? Kozyrev and you must be thinking you both are very smart guys, eh? Then I’ll show you. Be sure I’ll do that. Easily!” And he started explaining us how he would punish us. Then he exclaimed: “Just think of it—bombing Yugoslavia! (Yeltsin got the message right!) It’s the Americans who want to do that, isn’t it? But do we? This is not another Iraq. Tell Kozyrev right away to vote against the resolution, or at least to abstain.” I replied: “It was you who allowed Kozyrev to vote for that resolution.” “I don’t remember that, I don’t remember that,” was Yeltsin’s reply. A short while later he called back. “I have in front of me this memo on Yugoslavia. I never gave any permission.”

At this point it is worth explaining that once in a while Kozyrev played some tricks. This time on the same day, alongside Lavrov’s memo on Yugoslavia, he submitted to Yeltsin an account of his discussions in Washington. Apparently, nobody else apart from Deputy Foreign Minister Georgy Mamedov was aware of the contents of that memo. On page 10 or 11 (even in better days no one ever bothered to read that far in such documents) there was a paragraph that read: “If the French are not persuaded to make their proposal part of the overall set of measures, Russia should vote for the French draft.” Of course, no one had the slightest intention of persuading the French. At the end of that lengthy memo there was a draft resolution in favor of approving the submitted proposals. In fact, the president had not been told what the French resolution really meant. Such a situation made it possible to launch strikes against both air and ground targets.

So our position changed the very last minute after Yeltsin intervened. Some of his aides had probably put in a word. Good bless him! Regrettably, Yeltsin would later change his attitude once again. The resolution to use force eventually played a disastrous role. The only thing we succeeded in was to rule out attacks against ground targets. We managed to restore the phrase “in air space” to the final wording of the resolution, which had been inconspicuously removed shortly before. Had it not been for the battle that we staged over the resolution, we would have never achieved even that tiny bit.

We must admit that our international and legal efforts were all in vain. The U.S. and NATO eventually violated the decisions for which they had voted.

Another crackdown on the Serbs was timed for a Clinton-Yeltsin summit in April 1993 in Vancouver, Canada. The UN Security Council’s draft resolution concerned the introduction of additional economic sanctions against Yugoslavia. Kozyrev quickly sent a memo to Yeltsin in favor of new sanctions, without saying anything to us. He claimed that the sanctions agreed with our policy towards the Yugoslav crisis the way it was outlined in the presidential statement of 9 March, to the effect that there was no alternative to the Vance-Owen plan. In reality, the statement contained nothing like that. We actually backtracked on the elements of independence that remained part of our stance towards Yugoslavia.

The U.S. wanted to link international problems with promises of aid to us, which was the case with the pullout of Russian troops from the Baltic countries. At the time, I remember I thought that if we only had an opportunity to make a decision on sanctions against Yugoslavia at our discretion, without anyone pressuring us, would we ever agree to them? So the whole matter is external pressure. Would we be pressed so hard if Russia were not so weak? And if we had a different kind of leadership, would we really yield to pressure?

The U.S. Special Envoy to the UN told her Russian counterpart Yuli Vorontsov that accord with Russia over the draft resolution on the new sanctions should be reached before the Vancouver summit. The number one item on the agenda was the U.S. program for aid to Russia, and it is not the president’s job to look into UN resolutions. Strobe Talbott, the number two man in the U.S. State Department, in a private conversation with Russian Ambassador to the U.S. Vladimir Lukin and German Foreign Minister Klaus Kinkel publicly linked assistance to Russia and their countries’ policies towards Russia in general with our stance regarding the sanctions. Those two men did not mince words: do as you are told, or you will be left without our aid. In all fairness, that alone was a reason enough to veto the resolution.

The Americans were pushing us not only in New York and Washington. U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher called Deputy Foreign Minister Georgy Mamedov to say: “We would like to warn Russia against using the right of veto when the resolution is put to a vote in the UN Security Council, because that might harm U.S.-Russian relations. In particular, this may make it harder for the U.S. administration to secure congressional support for extending assistance to Russia.” In exchange for the promise of future aid, we were urged to make concessions right away.

Yeltsin read our memo and inscribed a very competent resolution: first, have a discussion at the Council of Ministers’ meeting about what sanctions are on the agenda; let the Foreign Ministry collect the opinions of all agencies concerned; and make a decision only after that. Alas, we would not be satisfied for long. On 18 April, the UN Security Council voted for a resolution to tighten sanctions against Belgrade. An Easter gift to all Orthodox Serbs indeed! It later turned out that Kozyrev and Vorontsov had been in contact with each other throughout that night. At five in the morning, Vorontsov was told to abstain and to refrain from vetoing the draft.

What was the reason for such haste? First, mediation efforts were not taken to the logical end. Second, there was no chance to study the likely economic implications for Russia. Kozyrev would later say in public that the financial losses Russia sustained as a result of sanctions by far outweighed the total amount of foreign aid it received from all sources. Third, we could backtrack on our promise to veto the resolution if it turned out to be ill-timed. Fourth, all along we had asked to postpone the vote until a domestic referendum on 25 April. Nobody agreed to wait. It was a very peculiar gift, indeed. Fifth, everybody noticed that we became afraid every time we were bullied. And sixth, how could anyone trust us if we did precisely the opposite of what we had said?

I tried to find out how the decision to abstain had been made. It turned out that at the very last moment the president, after listening to advice from the prime minister, changed Kozyrev’s “Aye” (originally, it was a firm “Nay”, proposed by Vorontsov) to “Abstain.” For quite some time Yeltsin had wanted to follow in China’s footsteps, which preferred to abstain as well. But that was tantamount to approving the resolution, to agree to sanctions mandatory for all, including Russia.

The U.S. and some other Western countries did not want a peace settlement while the Serbs were succeeding militarily. They postponed a political settlement through any means possible. Some countries proclaimed that air strikes should be launched against Serbian heavy artillery, and destroy bridges and roads used to deliver armaments and ammunition to Bosnia. Settlement would be considered only after the Serbs had been defeated, and after public opinion, shaped by TV clips showing cruelty and outrages, but only on one side, was satisfied. Furthermore, President Clinton had to fulfill both his campaign promises and his self-esteem as a resolute, albeit young president.

“A very shortsighted attitude” I wrote at the time. “Because the end effect of the escalation of pressuring the Serbs is anyone’s guess. Who can guarantee that the humiliated and defeated Serbs would agree to negotiate? Aware of the Western sentiment, the Albanians in Kosovo are prepared for saber rattling after a ten-year silence. Surely a great mess may follow.”

I am not editing my notes I took at the time to make them match what actually happened. In retrospect, I can only admit that it was not shortsightedness, but a systematic policy of weakening the Serbs, who were also seen as the main agents of Russian influence in the Balkans. It is also quite remarkable that the Westerners were very wrong in their perception of Milosevic, although it is true that he often urged us to persuade the West to ease pressure on him. But at the same time he would not reveal his plans to us. The Serbs did not make life easier for us, because they had no confidence in the Yeltsin team, which had voted for sanctions. They were waiting for a change of power in Russia. They would trust any such prophecy whispered in their ears by various emissaries from Moscow. It is to the Russian Foreign Ministry’s credit that it upset plans for a visit by Karadzic—the leader of the Bosnian Serbs—whose only desire was to talk with Supreme Soviet Speaker Ruslan Khasbulatov and Vice-President Alexander Rutskoi—in other words, with the opposition.

Our support for the Serbs was not a manifestation of Slavophilism, although the historical tradition cannot be denied completely. It is far more important that Yugoslavia was a testing ground for an international mechanism to dictate peace to parties in ethnic conflicts. That machinery bore an unmistakable ‘Made in the U.S.A.’ label. Russia failed to gain a place of its own. It is no accident that the Balkan settlement—which suited Western interests exclusively, with Russia playing only a secondary role—was presented as a template for other places.

This policy was also shortsighted. Flirting with Islamic fundamentalists in Bosnia added to their strength. There is credible evidence that the Bosnian Muslim leadership had deep and compromising links to the international jihadist movement. The leadership had hosted at least three key players in the 11 September 2001 attacks against the U.S. (as follows from what the International Herald Tribune wrote in December 2012).

THE TARGET IS SERBS

8 February 1994. It was good that my comrades and I had fought hard, but it was not good that we had let the UN Security Council pass the decision to use force to ensure a no-fly zone over Bosnia-Herzegovina. U.S. F-16s shot down four Serbian planes “on legal grounds.” It was NATO’s first combat operation in the history of the alliance. The overall situation worsened drastically. On 5 February 1994 an artillery shell exploded in the middle of a crowded Sunday market in Sarajevo, killing 69 and injuring over 200 people. The Serbs were blamed immediately, although further investigation would point to Muslim involvement. NATO sent the Serbs an ultimatum—all heavy weapons should be pulled back from Sarajevo. It is true that Serbian artillery had been shelling the defenseless city from the surrounding mountains. NATO warned the Bosnian Serbs that air strikes would follow if the Serbs did not pull back.

As we discussed the situation at the morning meeting in the foreign minister’s room, I suggested that Russia intervene by distancing itself from the NATO ultimatum, which had not been agreed on with us, and by asking the Serbs on our own behalf to withdraw their heavy weapons. Not because they were afraid of NATO, but on their own volition, because Russia was asking them to do so. The request should be made at the highest level. If the Serbs agreed, that was good; if not, our conscience would be clear—we had really tried to ward off a strike against them.

Kozyrev liked the idea and promptly took it to the president. Yeltsin sent Milosevic and Karadzic a special message. We backed up our words with action: we moved 400 “blue helmets”—part of our peacekeeping force deployed in Croatia under a UN mandate—to the Serbian-controlled areas around Sarajevo. For the Serbs, it worked as a guarantee against a possible attack by the Bosnians.

Our comprehensive initiative resulted in both a positive effect—even the Europeans recognized that (although not the U.S., of course!)—and a very unexpected one as well: the Serbs (and the Muslims) started removing their heavy armaments or placing them under UN control.

Yeltsin was very happy. On the list of those rewarded with a bonus for professionalism in implementing the presidential instruction regarding Bosnia, I saw my name. Regrettably, Russia would not build on that success.

The U.S. and NATO remained the main protagonists on the scene of Yugoslavia’s bloody tragedy.

Due to U.S. efforts, the war between the Croats and the Muslims ended in the spring of 1994 and a Croatian-Muslim federation was established in Bosnia. Now the U.S. had ‘a good guy’ worth supporting. The Federation began to quickly arm itself. The embargo on arms supplies to Bosnia-Herzegovina was full of holes as far as the Muslims were concerned. Similarly, the Germans were arming Croatia. International mediators were losing influence, because the UN placed the peace process in the hands of the Contact Group of five countries (Germany, France, Britain, the U.S., and Russia), where the U.S. had more leverage and Russia had no right to a veto.

By the summer of 1994, the Contact Group had delivered political settlement that was pretty close to what Vance (who would later be replaced by Thorvald Stoltenberg) and David Owen had proposed. The Contact Group’s key proposal boiled down to dividing Bosnia-Herzegovina: 51% would go to the Croat-Muslim Federation, and 49%, to the Bosnian Serbs, who founded the Bosnian Serb Republic, or Republika Srpska. The Americans were slightly deceitful. First they agreed on the map with the Muslims, who from that moment would enjoy outright U.S. support, and then they handed it over to the quintet. We were tasked with persuading the Serbs, on which we embarked immediately.

Milosevic accepted the U.S. idea: he was promised an easing or lifting of sanctions that were choking Yugoslavia. He even agreed to what the West had been demanding for quite some time; on 4 August 1994 he severed relations with the Bosnian Serb Republic and closed the border with it. Milosevic had sought to expand Serbian territory, and now he could position himself as an architect of peace. But Karadzic was a contender for the pan-Serbian leadership and was in no mood to cede it to Milosevic. This rivalry between two Serbian leaders weakened all three Serbian entities—in Yugoslavia, in Bosnia, and in Croatia. The fragmentation of the Serbs, and their miscalculations and self-assurance resulted in a situation where they were beaten one by one.

In early August 1994, the foreign ministers of the five Contact Group countries met in Geneva to declare that the consent of the Bosnian Serbs to agree with the Contract Group’s proposals (the Croat-Muslim Federation had already accepted them) should be the first step towards the resumption of the peace process.

It was an ultimatum, an iron fist in a velvet glove. It was carefully worded in a way that would make it hard for the Bosnian Serbs to say yes to the Contact Group’s offer. Possibly, it was very wrong for us to agree to this game of putting forward preconditions, all the more so because it would continue. The Americans saw to it that negotiations within the Contact Group were stalled repeatedly. Our attempts to influence them were feeble. The prolonged pause played into the hands of both the Muslims and the Croats, who, by relying on outside support, had built up considerable combat readiness. The pause was certainly detrimental to Bosnia’s Serbs, who had just lost Belgrade’s support.

On 1 May 1995, the Croats launched the first massive offensive using tanks, artillery, and aircraft. The Croats broke all links between the Croatian and Bosnian Serbs, for which they did not even stop short of attacking UN peacekeepers. It was all over in a couple of days. Fifteen thousand Serbs in Western Slavonia had to flee their homes. The Croatian offensive was synchronized with a Muslim attack in the area of the Posavina corridor. The Germans and the Americans were helping two parties in the conflict in their war against a third.

What did Russia do in this situation? A rather weak statement by the UN Security Council’s chairman was all that we managed to achieve. Our demand to impose sanctions on Croatia was brushed off.

Later in May 1995, NATO launched air strikes against the Serbs in Bosnia over our objections. NATO even bombed Pale, the capital of the Bosnian Serb Republic. Civilians and UN peacekeepers were killed, and dozens of others were taken hostage by both Serbs and Muslims. NATO decided to include not only Gorazde, but also other so-called security zones in the list of areas under its protection. Whenever they came under a Serbian attack, a strong rebuff followed. The Muslims continued to attack the Serbs through hit-and-run raids from areas that were never demilitarized.

The aim of the U.S. was pretty clear—end the war at the expense of the Serbs in favor of the Muslims and Croats. We kept grumbling and snapping back whenever the opportunity arose, only to give in to anti-Serbian policies in the end. Might makes right. We lacked the physical ability to prevent the Americans from doing what they were doing. What else could we do? Challenge and defy? Launch a public outcry? At least we could have made some dramatic gestures, such as a temporary walkout from the Contact Group to publicize the issue. At least we could have distanced ourselves from that. We did nothing.

On 4 August 1995, a one hundred-thousand-strong Croatian army (Tudjman had trained and armed it for three years) launched an offensive on a wide front to seize practically the entire territory of Serbian Krajina, including Knin. All 150,000 Serbs were forced from the land where they and their ancestors had lived for three hundred years. Both Milosevic and Karadzic, who had become commander-in-chief in his republic, remained out of the conflict. The Westerners confined themselves to more hypocritical calls addressed to the Croats again, while quietly rejoicing at this turn of events. Few took the trouble to recall that Serbian Krajina had been declared a territory under international protection. Carl Bildt, an international mediator in the Balkan conflict, was the only politician who, in a sense, saved the honor of the West by criticizing the Croatian government and mentioning President Tudjman in the context of war crimes. In retaliation, Croatia declared Bildt persona non grata. Thousands of homes were abandoned, looted, and set on fire. It was the worst ethnic cleansing during that war and a genuine humanitarian disaster.

Croatian General Ante Gotovina, whose troops massacred Serbs in Bosnian Krajina, faced the International Tribunal in The Hague only several years later. Many years later evidence surfaced that the Americans had not only armed and trained the Croatian army, they had also planned the operation against Krajina’s Serbs and provided intelligence, including drones that collected data. Opinions differ only on whether retired military or private firms were involved, or if the CIA and the Pentagon played a role too.

In the autumn of 2012, the UN tribunal in The Hague for former Yugoslavia, created especially for trying war criminals, ordered the release of General Gotovina and his accomplices. The same amount of “clemency” was shown towards Ramush Haradinaj, Kosovo’s former prime minister. The list of those convicted by that tribunal consists almost exclusively of Serbian names. Nobody has ever been brought to justice for ethnic cleansing against the Serbs or for the massacre of Krajina’s Serbian population.

When the last UN peacekeeper had left Bosnia, sixty NATO warplanes had pounded the positions and supply lines of Bosnian Serbs. This was carried out after an explosion at a Sarajevo market that was blamed on the Serbs immediately. More air strikes followed. An Anglo-French rapid deployment force joined in on the ground. That was the real purpose for its creation. Kozyrev, who had been told that it was a peacekeeping force, was deceived again. No one had bothered to ask the UN Security Council for permission to launch such a wide-scale use of force. There was a far-fetched reference to UN Security Council Resolution 836 and a preposterous mention of NATO resolutions allegedly “approved by the UN Secretary-General.” This is how international law was defied and trampled underfoot.

After NATO’s artillery bombardment, a 120,000-strong Muslim force and Croatian units went on the offensive. Again we confined ourselves to curses and threats that we would unilaterally lift sanctions against Yugoslavia. But we lacked the courage to act on our words.

At the same time that the Bosnian Serbs were being bombed, Milosevic met with Richard Holbrooke, Clinton’s envoy to the Balkans, in Belgrade for “peace talks.” Everything continued to proceed in the same dual fashion—dictating settlement terms and attacks against Bosnian Serbs, against an ever wider range of targets, including bridges, roads, and other infrastructure. NATO cracked down on a tiny population of 1.3 million at the most. Cruise missiles hit practically all Bosnian Serb facilities. NATO eliminated part of Serbia’s air defenses, which would prove very helpful to the alliance in 1999. In all, NATO warplanes flew 3,400 sorties. With NATO’s backing, the combined Muslim-Croatian force drove the Serbs back. A civilian exodus followed. The map of Bosnia-Herzegovina was changing every day. In the end its territory was divided along the 51%-49% pattern. The geography of that division was pretty close to what could have been adopted relatively peacefully back in the autumn of 1994 or even earlier, without plunging hundreds of thousands of people into the horror of war. Lord Owen, a competent insider, says outright that it was not only the Bosnian Serbs but also the U.S. government who made the war last that long.

The Balkan ordeal was coming to an end. In October 1995, the Americans imposed a ceasefire on the warring factions. On 1 November 1995, the Dayton peace talks began with the participation of Russia, although in the capacity of a backstage onlooker. Russia’s signature to the Dayton Accords imposed on the Serbs, which Owen would describe as a “disgrace,” merely emphasized Russia’s marginal role.

In Bosnia, Milosevic received far less than what the Serbs could have counted on, for he was afraid of returning to Belgrade with economic sanctions still in place. The Bosnian Serbs were leaving the areas to be taken over by the Muslims and the Croats, burning homes and digging up the remains of their ancestors. On 12 November 1995, Milosevic made the last concession to Tudjman by handing over Eastern Slavonia to Croatia, which became the most ethnically pure of all of the former Yugoslavia’s constituent republics. On 21 November 1995, the presidents of Bosnia, Croatia, and Serbia initialed the peace accords.

Forecasts regarding Milosevic’s own fate began to come true before long, for which he could largely blame himself. He was not allowed to do away with separatists in Kosovo. What seemed incredible in 1995 became a sinister reality in 1999. Starting in April 1999, the U.S. air force and those of other NATO countries pounded Serbia with 40,000 bombs and rockets—all without a mandate from the UN Security Council and in direct violation of the UN Charter. Moreover, NATO members abused the alliance’s charter. They were the first to attack a country that had not threatened the alliance’s security. Also, NATO violated the Russia-NATO Founding Act of 1997. The Yugoslav economy—factories, power plants, oil refineries, bridges and roads, and communication lines—was crippled. Thousands of civilians were killed. Eventually, Russia emerged at the forefront again. But what was its mission? To help the Americans get out of a dead end and to persuade Milosevic to accept NATO’s conditions. In the final count, borders inside an emasculated Serbia were destroyed. Serbia lost Kosovo—part of its own territory and the cradle of the Serbian nation.

One of my saddest and most unforgettable memories is my wife and I standing on a terrace of a hotel in Slovenia, basking in the lavish beauty of an Adriatic resort and hearing the roar of jet engines above as NATO planes made their way to their ‘targets’ in Belgrade and other cities in Serbia. The pilots of those planes were fully aware of their impunity. Fortunately, by that time I had quit civil service. My resignation was accepted in the summer of 1998.

A BRIEF AFTERWORD

The problems facing Russian foreign policy in the 1990s stemmed only in part from the desire of certain personalities who wanted to follow in the footsteps of a certain group of countries. The Soviet Union—a once mighty actor on the world stage— was abolished and hardly anyone will ever be able to say for how much longer it might have lasted as a geopolitical reality. Those who caused the Soviet Union to collapse got a weak Russia in return. It has taken a long time for Russia to earn the consideration the Soviet Union once held. Moreover, Russia’s ruling elite sought to remain in power by relying on outside support. Its precarious position at home was a consequence of the Soviet Union’s disqualification, too. Due to its chaotic foreign policy after December 1991, Russia was no longer a major global player. That fact never left me throughout the Yugoslav crisis.