“Nobody wants to acknowledge the dire reality that a state

of war—albeit hybrid war—already exists between Russia

and the entire democratic world.”

Peter Dickinson, The Atlantic Council, March 13, 2018

Following the Ukraine crisis and Russia’s interference in Ukrainian affairs in 2014, Western politicians and media have widely adopted the notion of hybrid warfare (HW) when characterizing Russia’s international behavior. European leaders, such as Angela Merkel, have described Russia’s actions, including hackers’ attacks on the German parliament in 2015, as a part of the Kremlin’s HW (Bennhold, 2020). Russian foreign policy overall—from Ukraine to wider Europe, Syria, Venezuela, Libya, and the United States—has been frequently assessed as reflecting Moscow’s global aggression against Western nations.

In this paper we show that, apart from political and media circles, experts, too, routinely exploit the HW language in their analysis. Although the language originates in the expert community (Friedman, 2018; Pynnöniemi and Minna Jokela, 2020), a number of analysts have criticized it as underspecified, based on unrealistic assumptions, and overall prone to rather obscuring than clarifying Russia’s international behavior (Kofman, 2016; Monaghan, 2016; Renz, 2018). Other analysts have argued that, despite the reputation of being objective and non-partisan, experts frequently validate concepts and ideas popular within the dominant elite circles, thereby becoming victims of political groupthink (Beebe 2019). We maintain that this phenomenon has roots in political biases of the organizations with which experts are affiliated. In particular, the HW language is employed by those political groups and institutions that are convinced that the Kremlin is solely responsible for the current crisis in relations with the West and that solutions could only arise from applying strong pressure on the Kremlin to alter its international behavior.

To support this argument, we have taken a closer look into the Atlantic Council (AC), an American think tank with clear preferences for preserving the United States-centered international order and expanding NATO as the foundation of security in Europe. We base our analysis on a sample of articles on Russia and “hybrid war” published by the AC’s experts between 2014 and 2020. In establishing the AC’s pro-NATO and anti-Russian biases, we analyze the articles’ frames as well as political and institutional preferences held by the organization.

The AC plays an important role in Western political and media circles. The AC leadership includes former U.S. ambassadors and other prominent government officials. The organization serves as a platform from which policymakers and politicians articulate their views. AC experts are present at important Western conferences such as the Munich Security Conference, and their views are commonly cited and rarely challenged in Western media. Alternative perspectives on international events and U.S. foreign policy preferences exist but lack comparable political and media support. While presenting itself as bipartisan in the U.S. political context, the AC reflects international security preferences shared by Western powers. The organization’s perspective may align well with that of the Biden administration. However, Western preferences are generally not shared by non-Western powers, including China, Russia, Turkey, and others. These preferences favor going beyond West-centered power and security alliances such as NATO.

This paper is organized in three sections. The first section proposes a framework for assessing expert knowledge, particularly the one produced under the pressure of international crises. The next section focuses on the AC’s writing on Russian foreign policy since the Ukraine crisis in 2014 and explains the methodology of our discourse analysis in greater detail. The final section develops an explanation for our argument regarding the AC’s views of Russia and European security by providing evidence of the organization’s political bias. The conclusion summarizes our findings and discusses their possible implications for political expertise and the West’s relations with Russia in the future.

International Crises and the U.S.-Russia Expertise

International Crises, Politics, and Knowledge

Scholars have long established that knowledge about international affairs often reflects political, cultural, and geographic biases of those who produce it. For example, post-colonial studies exposed American mainstream approaches as “parochial,” not global or reflecting intellectual assumptions and political preferences of those in the center of the international system. To address these biases, post-colonial scholars proposed to conceptualize relations between the Self and the Other in a reciprocal manner by treating others as a source of knowledge and policy solutions, rather than dependent subjects (“subaltern”) (Said, 1993; Oren, 1998; Inayatullah and Blaney, 2004; Hobson, 2012; Turton, 2015; Vitalis, 2015). Those working outside post-colonialism and post-structuralism agree that scholarly biases are common and widespread. Some of these scholars committed to neopositivist thinking found that American dominance in the field tends to create “blind spots” in international relations, thereby negatively affecting IR scholarship (Colgan, 2019a; Levin and Trager, 2019). Political and cultural biases also affect rating agencies and databases, resulting in one-sided assessments and recommendations (Cooley and Snyder, 2015; Tsygankov and Parker, 2015; Bush, 2019; Colgan, 2019b).

International crises and security dilemmas create conditions under which the production of objective and non-biased knowledge becomes ever more challenging.

When a crisis evolves into a political and military confrontation, intellectuals are hard-pressed to side with their governments and some may even be viewed as national traitors if they are critical of their own states. Under these conditions, negative attitudes and stereotypes dominate. States are pressured to present themselves as the ultimate protectors of national interests and can be tempted to engage in nationalist mythmaking, fear-mongering, and strategic cover-ups (Mearsheimer, 2011).

Examples of how international crises affect the expertise are plentiful. Researchers have found that during the Cold War many experts on the Soviet Union exaggerated the threat by presenting the Soviet other as the existential opponent and mirror image of America (Dalby, 1988; Oren, 2002; Foglesong, 2007). Following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, Americans experienced a revival of Islamophobia not only in the media (on media coverage during international crises, see Simons, 2010; Boyd-Barrett, 2016), but in the think tanks and academic circles as well (Ali, 2003; Beydoun, 2018).

In contrast, the non-biased, objective expertise in America remains in short supply. According to Tom Nichols (2017), such expertise has been replaced by ignorance and anti-intellectual sentiments, as technology and dissemination of information has led to the excessive confidence among ordinary people that everyone knows everything. Daniel Drezner (2017) has found that in the context of political polarization, social inequality, and mistrust in the authorities, intellectuals are pressured to produce big and bold ideas, such as ending global poverty by 2025, even if such ideas may not hold up under scrutiny by specialists. Amplifying the erosion of trust in expertise, other scholars have pointed out the arrival of post-truth in the age of populism, as well as institutional decline, where facts no longer matter and are exploited or invented by politicians to their advantage (Pomerantsev, 2014; Montgomery, 2017).

The Ukraine Crisis, Nato, and Russia

The Ukraine crisis served to exacerbate tensions between Russia and Western nations in areas of security and political relations. Scholars have assessed the crisis as a security dilemma, in which different sides view actions of the other as offensive, requiring national defense and military mobilization (Colton and Charap, 2017). Securitization has affected not only international policy but various dimensions of domestic policy as well, including media coverage of events by different sides (Boyd-Barrett, 2016; Gaufman, 2017).

These conditions have prompted experts to develop at least three distinct narratives of the Ukraine crisis and Russia’s role in it. The dominant Western narrative has been that of Russia’s aggression as the root cause of the crisis, resulting in the annexation of Crimea and destabilization of Eastern Ukraine. According to this narrative, the Kremlin acted on the fear of increasing domestic instability of Vladimir Putin’s regime and Russia’s old imperial instincts (McFaul, 2014; Sestanovich, 2014). Ukraine was a victim of Russia’s power ambitions, while the United States and the European Union had little choices but defend Ukrainian sovereignty by imposing sanctions against Russia and demanding its compliance with international law. Under this narrative, the West also had to mobilize NATO and its military capabilities in order to deter the Kremlin and prevent its new invasion inside Ukraine and/or wider Europe.

The second narrative reveals more complex roots of the crisis, including those concerning actions by Western nations preceding the 2014 developments. Analysts in this group have identified various Russia-West interactive dynamics responsible for the exacerbation of international tensions since the breakup of the USSR in 1991. They acknowledge that Russia indeed violated the international law, but they also argue that the Kremlin did so in response to Russia’s several principal interests, which were not considered by the West (Sakwa, 2016; Kanet, 2017). These interests are deeply connected to Ukraine and include the transportation of Russian energy to European markets and participation in European security institutions. These analysts have also identified Ukraine’s own contribution to the crisis by failing to build a functional state that could accommodate its politically and ethnically diverse population (Kudelia, 2014; Driscoll, 2019).

Finally, there are analysts in Russia and the West who attribute responsibility for the Ukraine crisis entirely to the Western nations. They view actions by Russia as an expected response of a great power to the West’s insensitive and potentially offensive policies, such as the expansion of NATO and the EU, as well as support for regime change in the countries adjacent to Russia.

This narrative has been dominant in Russia and is only occasionally voiced outside of it (the exception is Mearsheimer, 2014).

The HW Narrative and the U.S.-Russia Experts

The emergence and the spread of HW narrative were made possible in the United States due to an atmosphere of international confrontation and the dominant perception of Russia as responsible for the Ukraine crisis. Ironically, while the attribution of HW strategy to Russia became more common among Western analysts, Russian analysts employed the HW language to explain Western military preparations against Russia. In 2014, military analyst Mark Galeotti posted a translation of the Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces, General Valery Gerasimov’s paper on his blog. The paper was intended to alert the Russian military establishment to dangers posed by Western hybrid warfare. Within months, the paper spread in political and expert circles as a definitive description of Russia’s “Gerasimov doctrine,” introduced for destabilizing Ukraine and other countries.[1] Presently, scholars also view the doctrine as a blueprint for Russian foreign policy in relations with the West (Orenstein, 2018).

The HW narrative is based on three main assumptions. First, Russia is viewed as an expansionist power prepared to blend military and non-military tools to accomplish its goals. Second, the “Gerasimov doctrine” is intended to guide foreign policy and foreign relations. Therefore, the drivers and techniques of Russian foreign policy described in the “doctrine” apply not only to Ukraine, but anywhere in the world. Third, while the Western nations and Ukraine are on the same side in the new confrontation with Russia, they are not well protected from a new aggression by the Kremlin. In order to provide adequate protection, they must deploy all available resources to counter propaganda and deter military action.

Since the introduction of the HW narrative, several Western military experts have criticized it as underspecified and potentially misleading. In their assessment, the realities of the Ukraine crisis have not principally changed Russian foreign policy goals, which have been rather stable since the mid-1990s. Some of these goals include preservation of great power status and influence in Eurasia and Europe (Rumer, 2020; Gorenburg, 2020). According to these experts, the HW has been more about the means than a goal and those two should not be confused. Overall, as Wither put it, “it is misleading and potentially dangerous to describe Russia’s broader aims and methods as simply a form of warfare” (2016, p. 80). Other analysts have pointed out that even in considering means or methods of Russian foreign policy during a crisis, the Kremlin tends to prioritize conventional military capabilities over any other means (Kofman, 2016; Renz, 2018). For example, Russia’s military tactics with respect to the annexation of Crimea, while differing from those in other theaters, still predominantly relied on conventional military presence in the peninsula (Kofman, 2016).

Experts critical of the HW narrative have also cautioned against overreliance on Ukrainian sources in assessing Russia’s actions (Zhukov, 2017). They further proposed that appropriate Western response to Russian foreign policy should combine firmness/deterrence with dialogue. Such response should not stem from a fear of the West’s principal weakness relative to Russia. These scholars argue that instead of deploying the Kremlin-like propaganda against Russia, it is important to be guided by confidence in Western institutions and open political discourse (Wither, 2016, p. 83; Wigell, 2019).

The AC’s Perspective on Russia and HW

Data and Methodology

This paper aims to test the theory of partisan politics by selecting an organization with political biases and investigating whether expert writings reflect these biases. We have selected the AC as representative of a politically partisan organization. In particular, the AC favors and advocates the U.S.-centered international order, NATO-centered European security, and perception of Russia as the main threat to European and global security. The AC also deserves to be studied as an organization with strong connections in the Western policy establishment and the ability to influence the decision-making process in the United States and other Western countries. The organization’s leadership and board of directors include former commanders of NATO, advisors to U.S. presidents, U.S. ambassadors, and officials at the Department of State and the Department of Defense (AC, 2020).

We have focused on assessing the writings by the AC between 2014 and 2020. This period was selected as representative of an international crisis, namely the Ukraine crisis that has roots in the Euromaidan revolution and the annexation of Crimea by Russia in March 2014. It is in the context of this crisis that the HW language has emerged and been adopted by Western experts, particularly those affiliated with the AC. We expect to find that the AC analysis, conceptual categories, and ways of framing issues related to Russian foreign policy reflect the indicated pro-Atlantic and anti-Russian biases of the organization.

Evidence for our assessment is provided by the textual analysis of all articles by AC experts published on the organization’s website during the period of 2014 through mid-2020. To obtain a sample of expert articles, we searched for “Russia and hybrid war” on the AC’s website. The search resulted in 42 articles and reports in total devoted to the analysis of various dimensions of Russian foreign policy. We then read the retrieved articles closely to identify their main themes and conceptual frames.

Main Themes

Overall, the AC experts are highly critical of Russia and its role in Ukraine, wider Europe, and the international system. The experts often link Russian foreign policy to the country’s leadership and political system, of which they are highly critical as well. The selection of themes and their dimension reveal their desire to highlight Russia’s negative role in the international order while omitting those of its actions that could show its leadership’s readiness for dialogue, negotiations, and cooperation.

With respect to Russia’s actions in Ukraine, the AC experts focus on the annexation of Crimea (Dickinson, 2016, 2017, 2018; Goncharenko, 2020), assistance to separatists in Eastern Ukraine (Grizian, 2015; Umland, 2016; Zimmerman, 2017), and the Kremlin’s failure to fulfill its international obligations, such as those reflected in the Budapest Memorandum signed on December 5, 1994 (Reznikov, 2020). The Memorandum was signed by the U.S., Great Britain and Russia, and provided security guarantees to Ukraine that relinquished its nuclear weapons. There are also a few experts who have analyzed Russia’s role in the Ukrainian presidential election in 2019, which resulted in the victory of Vladimir Zelensky over Pyotr Poroshenko (Dickinson, 2019), as well as the exchange of prisoners between Russia and Ukraine (Kararnycky, 2020).

AC experts attribute the responsibility for the crisis and instability in Ukraine entirely to Russia’s actions. They argue that the response of the United States and Western nations on the whole, to the Kremlin’s action in Ukraine has been inappropriately weak (Dickinson, 2016, 2017, 2018; Herbst, 2017; Kols, 2018; Blank, 2020; Goncharenko, 2020; Reznikov, 2020). To remedy the situation, they propose supplying Kiev with lethal weapons (Herbst, 2017), building up the U.S. Navy presence in the Black Sea region (Blank, 2020), strengthening NATO’s military capability (Galeotti, 2015; NATO’s counter, 2019), offering Ukraine membership in NATO (Goncharenko, 2020), cutting Russia off from from the international financial system (Dickinson, 2018b), and separating Ukraine from Russia’s energy networks (Bielkova and Aslund, 2017).

The topic of energy is also emphasized by those discussing Russia’s relations with wider Europe and the European Union. Here, the topics include the Kremlin’s propaganda, energy trade, and security preparations outside of Ukraine. AC experts present Russia’s media presence in Europe as an essential part of the Kremlin’s HW, calling for a firm political response and additional funds for the West’s counter-propaganda (Vrabel, Janda and Vichova, 2016; Poliakova, 2017; Forsyth, 2016). One writer has linked the conviction of a Ukrainian Nazi by an Italian court to Russia’s propaganda and HW (Tokariuk, 2019). Several experts analyze Russia’s role in Germany, expressing strong criticism of what they see as Germany’s excessive dependence on Russian natural gas (Umland, 2016; Dickinson, 2016; Forsyth, 2016). Others advocate stronger steps by NATO to prevent Russia’s possible attack against the Baltic states, Moldova, or other parts of Europe (Dickinson, 2017; Kols, 2018; Gerasimchuk, 2020).

Several analysts have focused on Russia’s presentations of World War II memories. These analysts argue that the Kremlin has “weaponized” such memories (Yelchenko, 2020) and caution against trusting Russian media and officials (Czolij, 2020). The Ukrainian ambassador to the United States argues that the Soviet Union entered the war in September 1939 as an ally of Nazi Germany (Yelchenko, 2020), a claim that is strongly denied by Russia (Putin, 2020). Another expert has condemned the joint statement issued by Russian and American presidents in commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the meeting between Soviet and U.S. troops on the River Elbe, which was marked in April of 2020 (Czolij, 2020). The writer views the statement as an attempt by the Kremlin to exploit the United States’ goodwill and distract attention from “reasons to be distrustful of today’s Russia” (Ibid).

In particular, they have called for a decisive strategy of counter-propaganda in regards to media and information, arguing against Donald Trump’s “limited” budget for said purpose (Poliakova, 2017).

Finally, AC experts discussing individual issues tend to make generalizations from their analysis claiming that the Kremlin has developed a foreign policy strategy aimed at attacking the United States and the West globally. Ukraine’s Deputy Prime Minister Alexei Reznikov (2020) writes: “Widespread disinformation campaigns in Europe and the U.S., cyberattacks, support for radical political movements, assassinations everywhere from Salisbury to Berlin, an attempted armed coup in Montenegro, and military interventions in Syria and Libya are all aspects of the Kremlin’s hybrid warfare that extend directly from the failure to stop the Russian aggression in Ukraine.” Generally supporting the idea of Russia’s global HW framework, Zimmerman (2017) and Dickinson (2018b) argue that it preceded the 2014 crisis. Thus, Dickinson traces the crisis as far back as 2004, to the poisoning of Ukrainian presidential candidate Victor Yushchenko. He also attributes the 2006 murder of Alexander Litvinenko in London, the 2007 cyberattack on Estonia and other actions to Russia’s global HW framework.

Frames

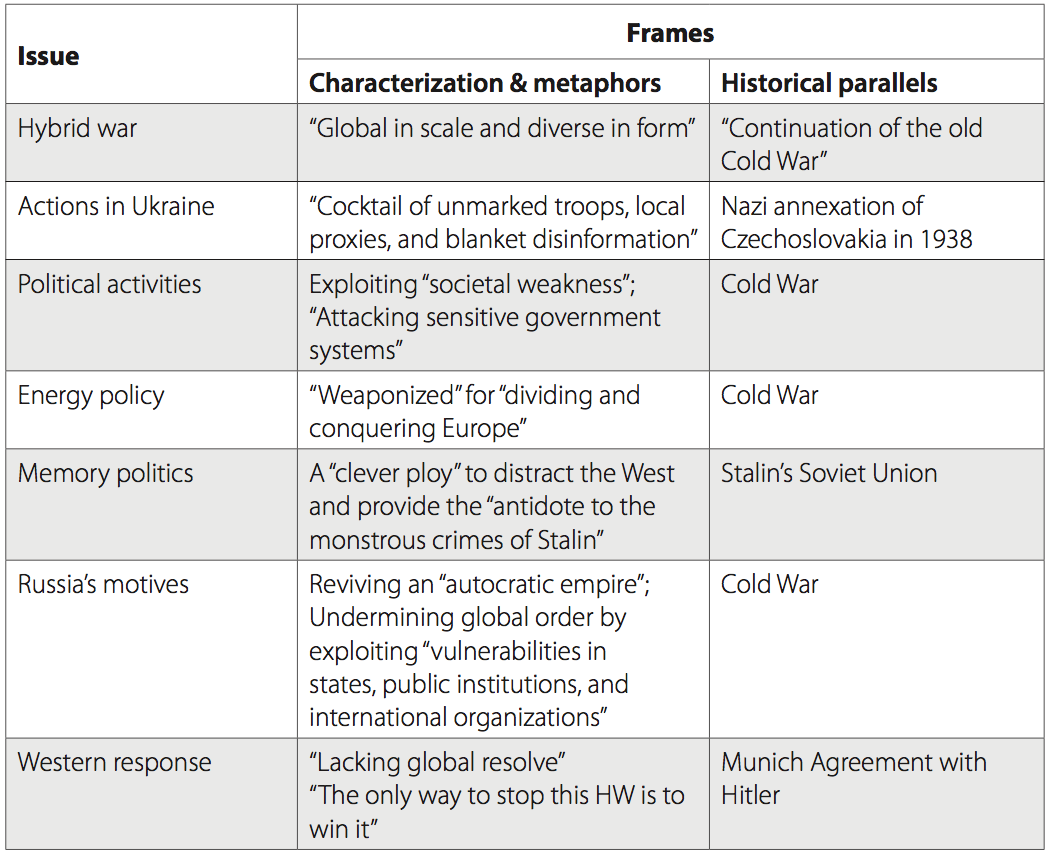

As evident from the above description, the overall tone of the AC experts with respect to Russia has been overwhelmingly negative, which contrasts with the generally positive attitude towards Ukraine and Western countries. This section strengthens this argument by shifting from descriptive to analytical categories, or frames, used for characterizing Russia’s actions and motives, as well as the corresponding Western response.

Table 1 provides a summary of the identified frames used by AC experts in their analyses.

Table 1. The AC’s Frames of Russia

Source: The AC’s analyses of Russia, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org

AC experts collectively characterize Russian foreign policy towards Western countries as a global hybrid war by a “hostile nation” (Dickinson, 2018b) with the overall objective to undermine, and ideally destroy, the Western international order. Similar to the old Cold War, this hybrid war is “global in scale and diverse in form” (Czoliy, 2020), ranging from military interventions to cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, and covert interferences in the internal affairs of Western nations. Russia’s “individual offenses” are viewed as “component parts of a single coordinated global campaign” “from Crimea to Salisbury” (Dickinson, 2019).

One prominent front in this global HW is Ukraine, where AC experts argue Russia acts in the manner of Nazi Germany before the Second World War (Gerasimchuk, 2015; Goncharenko, 2020). These experts present actions by Russia as a “cocktail of unmarked troops, local proxies, and blanket disinformation” with the objective of splitting or annexing Ukraine. In achieving this objective, the Kremlin will stop at nothing. Its HW has already “killed over 13,000 Ukrainians and left millions of lives in tatters” (Dickinson, 2019).

Outside of Ukraine, another front AC experts focus on is that which concerns Russian political and media activities in the global and Western information space. Here the Kremlin seeks to exploit any societal weaknesses or vulnerabilities in its information offensive. Some AC writers assume that Russia will not only “fan and inflame” ethnic, religious, political, and separatist tensions “at every opportunity,” but will also not hesitate to “unleash chemical weapons on civil population,” as it did with poisoning spy defector Sergei Skrypal (Dickinson, 2018b).

With respect to Russia’s energy policy in Europe, AC experts unanimously oppose the Kremlin’s projects, particularly Nord Stream 2, viewing such projects as a “weaponized” mechanism “for dividing and conquering Europe” (Bielkova, 2016; Bielkova and Aslund, 2017). The Ukrainian natural gas network Naftogaz is presented as highly dependable vis-a-vis the unreliable Russian network, Gazprom (Ibid). The AC writers are keen on stressing that Germany, Gazprom’s partner in the Nord Stream 2 project, is targeted by Russian security services by “subversively employing two tactics formerly used by the Soviet KGB: destabilization and misinformation” with the “ultimate goal of toppling Chancellor Angela Merkel” (Forsyth, 2016).

Russia’s memory politics and insistence on the joint Soviet-Western front against Nazi Germany is presented by an AC writer as a “clever ploy” to distract Western attention from Russia’s genuinely “aggressive actions” and “blatant violations” of the country’s international obligations (Czoliy, 2020). The “cynical use of World War II” has also assisted Putin domestically by bolstering national pride and countering the feelings of shame and humiliation for Stalin’s crimes (Ibid).

What are Russia’s motives in its relations with the West? In the view of AC writers, its motives are twofold: restoring an “autocratic empire” in Eurasia and destroying the Western-centered international order. The first goal is directly linked to the revival of the “three hundred years of Russian dominance over Ukraine” (Dickinson 2019). The second goal requires wide-spread destabilization of Western nations, including the Russian-controlled “gray zone” in Eastern Ukraine (Kols, 2018; Blank, 2020; Reznikov, 2020)

Those writing about Ukraine are not comfortable with the Minsk format for negotiating the settlement between Kiev and separatist eastern territories, despite the fact that the format was accepted by France and Germany. The Minsk format requires Ukraine to engage in direct negotiations with separatists before the control over the border with Russia is established. Kiev would prefer to restore control over Donbas unilaterally. As a result, the Ukrainian government seeks to sabotage the Minsk format and calls for the establishment of the Budapest framework (Reznikov, 2020). The latter would allow Ukraine to bring the United States and Great Britain into the negotiation process by increasing pressure on Russia and ignoring negotiations with Eastern Ukraine.

Overall, AC experts are convinced that Russia can only be treated as a “hostile nation” and the “only way to stop this hybrid war is to win it” (Dickinson, 2018b). However, the West is far from being united against the Russian threat, and the real challenge is to unite “against Russia’s global hybrid war campaign rather than react piecemeal to each individual outrage,” assembling a “global resolve” to confront the Kremlin (Ibid). Multiple AC writers have blamed Western nations, specifically Germany and France, for being soft on Putin, thereby acting in the manner reminiscent of the Munich Agreement with Adolf Hitler in 1938 (Gerasymchuk, 2015; Forsyth, 2016; Goncharenko, 2020).

Explaining the AC Biases

Beliefs And Biases Of The U.S. Establishment

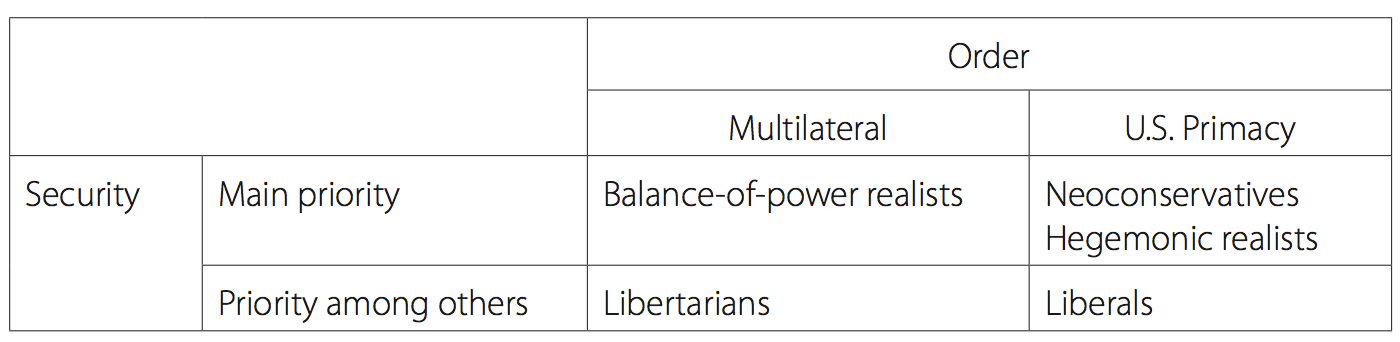

Within the American establishment, several groups demonstrate the belief in U.S. global primacy—liberals, neoconservatives, and hegemonic realists. Liberals advocate U.S. primacy and NATO expansion as essential for preserving the global institutional order and promoting democracy. As explained by Joe Biden (2020), “No other nation has that capacity.” Russia views both U.S. global primacy and the centrality of NATO in Europe as potentially harmful for international stability and security (Kanet, 2017; Rumer, 2020). Neoconservatives (neocons) and hegemonic realists defend U.S. military primacy as they view it as an essential foundation of American national security. Neocons go even further than realists by insisting that the United States cannot be fully secure without transforming other states, such as Russia in particular, in the image of American democracy (for details about U.S. foreign policy preferences see Porter, 2018).

Table 2 summarizes beliefs held by the American political class about foreign policy priorities.

Table 2. American Beliefs about Foreign Policy Priorities: Security vs. Order

Each identified group includes members of the political class and expert community. Well-known liberal think tanks include the Brookings Institution, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and the Center for American Progress. The latter was established by Hillary Clinton following the election of Donald Trump as president in order to challenge his views from the position of U.S. liberal primacy. Neoconservative views are frequently articulated by the American Enterprise Institute and, partly, by the Heritage Foundation and the Hudson Institute, whereas the hegemonic realist perspective is occasionally expressed in reports by military think tanks, such as RAND Corporation. There are also think tanks with less distinctive ideological profiles that include individuals sharing diverse beliefs in U.S. primacy. For example, the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC, and the AC are umbrella organizations incorporating such diverse views held by the primacy establishment.

The above perspectives are opposed by two groups with considerably smaller influence on policymaking—balance-of-power realists and libertarians. Neither group supports the idea of U.S. primacy. Realists do not share the belief in promoting democracy, but rather they advocate for more traditional tools of diplomacy, intelligence, and military build-up. They believe the U.S. must adapt to an (increasingly) multipolar world by developing offshore balancing strategies in various regions and focusing on containing China (Posen, 2013; Walt, 2018). Libertarians are equally critical of the idea of U.S. primacy, but their criticism has more to do with concerns of preserving democracy at home than with national security (Porter, 2018; Bacevich, 2020).

In the expert community, realist and libertarian views are expressed in particular by the CATO Institute and the newly established Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. The Center for National Interest led by Dimitri Simes holds a distinct realist perspective and publishes a realist-minded journal titled The National Interest (for analyses of U.S. think tanks, see Medvetz, 2012; Drezner, 2017; Salas-Porras and Murray, 2017).

The AC Bias for U.S. Primacy and NATO Expansion

The AC’s worldview is representative of dominant groups within the U.S. establishment. These groups view American primacy as central to global stability, NATO as the foundation of European security, and Russia as the main threat in both global and European settings.

Independent media watchdog organizations such as Media Bias/Fact Check found that the AC was publishing factual information that, nonetheless, utilized loaded concepts while attempting to appeal to stereotypes and influence the audience’s emotions in favor of the AC’s “conservative causes.” These causes and biases were found to be based in the AC’s “pro-corporate and hawkish military perspectives” (Media Bias/Fact Check, 2020).

The AC’s bias towards U.S. primacy is reflected in the organization’s mission, as well as the preference of board members, funding, and activities.

With the involvement of former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, and several other individuals, the idea was to bring together states working towards Atlantic unity (Small, 1998, pp. 4-6). Its close ties to the U.S. government were clear from the outset and evident in the involvement of key officials. For instance, Secretary of State Dean Rusk called a key meeting to unify the AC and other Atlantic organizations to be held in his office on July 24, 1961 (Ibid, p. 9). In attendance were chief donors, such as the Ford Foundation and former U.S. ambassadors to NATO, as well as other influential individuals.

The current mission of the organization is to “galvanize U.S. leadership and engagement in the world, in partnership with allies and partners” (Our Mission, 2020). The authors of the mission statement maintain that through their paper, ideas, and actions the AC “shapes policy choices and strategies to create a more free, secure, and prosperous world” (Ibid). This is not a mission likely to be accepted by the above-identified balance-of-power realists and libertarians. That said, the dominant groups of liberals, neoconservatives, and hegemonic realists may potentially agree on the mission. The latter groups are likely to converge on the leadership idea while diverging on its possible definitions and the means to achieve such leadership.

The AC leadership has historically included people with experience in the State Department and defense matters. These individuals include former U.S. Ambassador to China and Russia Jon Huntsman, former U.S. Ambassador to Uzbekistan and Ukraine John E. Herbst, former U.S. Special Envoy for the Sahel Region of Africa John Peter Pham, former Under Secretary of the Treasury in the U.S. State Department David McCormick, and others. Individual profiles of the AC board members further support its bias for global primacy and NATO expansion. The organization’s President and CEO is Frederick Kempe, a long-standing advocate of trans-Atlantic relations and NATO, and an expert on the Cold War. Other board members include individuals with various Cold War, NATO, and defense policy experiences. This includes Chairman John F.W. Rogers, former assistant to President Ronald Reagan in 1981-1985, Executive Chairman Emeritus James L. Jones, Jr, former Commander of all NATO forces, Chairman Emeritus Brent Scowcroft, former National Security Advisor to Presidents Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush, Executive Vice Chair Stephen J. Hadley, former Assistant Secretary of Defense in 1989-1993, and others (Board of Directors, 2020).

In terms of financing, the AC’s financial support initially came from the Ford Foundation that was interested in trans-Atlantic cooperation which helped to launch the AC with a five-year grant of $250,000. The Ford Foundation remained the chief donor from 1969 through 1973 (Small, 1998, p. 7). Today’s funders are more diverse and include donations from more than twenty-five foreign governments—most prominently the British government and the United Arab Emirates—wealthy individuals, and U.S. corporations such as Facebook, Goldman Sachs, the Rockefeller Foundation, and others.[2] Burisma Holdings, a company owned by a Ukrainian tycoon, Nikolai Zlochevsky, is also among the donors, contributing $100,000 to the AC per year for three consecutive years beginning in 2016 (Grove and Cullison, 2019).

The AC’s diverse activities include attempts to educate the public, as well as influence elites and policymakers by publishing articles, reports, newsletters and an academic journal. Individuals tied to the AC also attend and organize various events and conferences with the involvement of high-profile officials committed to U.S. primacy and strong trans-Atlantic relations. By the mid-1970’s the Atlantic Council was producing a variety of policy papers, books, and other works. In 1998 the Council organized a large international conference that was focused on rebuilding East-West relations. This shift continued with the fall of communism as much of the focus had shifted to Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and nuclear security.

The AC’s contemporary activities include providing a meeting place for heads of state, the military, and politicians from either side of the Atlantic including those aspiring to join NATO such as leaders of Ukraine and Georgia. Former NATO Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen, members of the U.S. Congress, and military commanders, including former General George Casey and former Admiral Timothy Keating also participated in AC activities by delivering speeches at the organization’s events.

Furthermore, the AC lobbies its cause at major international gatherings such as the Munich Security Conference, which is held annually in Germany. For example, on February 22, 2019, the AC released its Declaration of Principles outlining common trans-Atlantic values as a response to the perceived weakening of, and commitment to, these values at home and abroad. The AC’s President, Fred Kempe (2019), articulated the perceived fears by arguing that the public should not be “misled by media reports on Trumpian tweets that suggest the U.S. will weaken or even withdraw from NATO,” and that the era of U.S.- and NATO-centered international prosperity should continue, despite being faced with rising threats from China, Russia, and other “authoritarians.”

The Anti-Russian Bias: Russia as the Hybrid Warrior

The AC’s anti-Russian bias has roots in beliefs by the dominant U.S. groups that view both American global primacy and an expansion of NATO as essential for preserving peace and security in the world. These groups view Russia as a principal threat to the Western “liberal world order” partly due to Russia’s long-standing opposition to NATO expansion. In response to these biases, Russia took action to prevent the AC from operating in Russian territory, labeling it as an organization that is “undesirable,” posing a threat to the constitutional system and the security of the Russian Federation (Interfax, 2019).

Following Russia’s newly assertive foreign policy witnessed since the mid-2000s, liberals within the U.S. establishment have concluded that the Kremlin’s actions reflect the regime’s authoritarian nature, something they feel has been confirmed in Ukraine. Liberals tend to view NATO as an alliance of democracies that helps expand the space for democratic politics, and they do not accept the fact that Russia feels threatened by NATO. Neoconservatives view the trans-Atlantic alliance through the lens of security, but also favor the promotion of democracy as a way to secure America’s global hegemony (on the belief in democracy for security’s sake, see Tsygankov and Parker, 2015). Finally, hegemonic realists do not prioritize democracy, but rather insist on expanding NATO for the reasons of national security and power.

It follows that each of the identified dominant groups has its own reasons for viewing Russia as a key threat, but still, they converge on the idea of Russia as a quintessential hybrid warrior that fights Western values, security, and global status (for other examples of major U.S. foreign policy groups’ convergence on Russia perception, see Tsygankov, 2009; Tsygankov and Parker, 2015). Rather than adopting a limited and nuanced perspective on Russian foreign policy advocated by the HW critics, the AC seems to view the world through a lens that reflects U.S. dominance and Western security perspectives. In turn, they assume the HW to be Russia’s ultimate method for undermining the U.S.-centered world order.

* * *

As the world enters a period of transition to a new international order, the uncertainty that accompanies the process presents a challenge for independent, non-partisan expertise. In some cases, it results in fears of instability and diversions of blame rather than objective analysis. In this paper, we have selected the AC as representative of an organization with a partisan political agenda. This organization’s agenda promotes the U.S.-centered international order and the NATO-based European security system. As a political and advocacy organization, the AC also has the ambition to serve as a think tank with the capacity for objective analysis and policy recommendations. Its views are well-represented in the organization’s policy reports, statements, and expert analyses. The AC experts are known for their support of controversial U.S. foreign policy decisions including the intervention in Iraq in 2003 and Libya in 2009. With respect to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the AC experts have frequently challenged the Minsk format advocating additional Western pressures on Russia as the only effective way to resolve the conflict.

Experts at the AC overwhelmingly view Russia as the main security threat to the U.S., rather than a potential party in dialogue and crisis resolution. Their analysis grounded in the notion of Putin’s “global HW” lacks the nuance and proportion required for understanding Russia’s issue-specific objectives. In the words of one critic, “if the West is to come up with a political and military strategy that deals with Russia, it must start by killing bad narratives and malformed analysis: Russian hybrid warfare should be the first on that list” (Kofman, 2016). A balanced approach to Russia should avoid partisanship and be based on objective and self-critical expertise. The politically polarizing international transition places an especially high premium on such expertise.

This research has been supported by the Interdisciplinary Scientific and Educational School of Moscow University “Preservation of the World Cultural and Historical Heritage.”

References

Ali, Tariq, 2003. The Clash of Fundamentalisms. London: Verso.

Bacevich, A., 2020. Joe Biden’s Foreign Policy Gave Us Donald Trump. American Conservative, 20 April.

Beebe, G., 2019. Groupthink Resurgent. The National Interest, 29 December.

Bennhold, K., 2020. Merkel Is ‘Outraged’ by Russian Hack but Struggling to Respond. The New York Times, 13 May.

Bielkova, O., 2016. Here’s Why Nord Stream 2 Isn’t the Only Game in Town. The Atlantic Council, 9 September.

Bielkova, O., and Aslund, A., 2017. How to Keep the Russian Bear Out of Ukraine’s Energy Sector. The Atlantic Council, 29 September.

Beydoun, K.A., 2018. American Islamophobia. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Blank, S., 2020. U.S. Should Revive Lend-Lease to Contain Russia. The Atlantic Council, 2 May.

Board of Directors, 2020. The Atlantic Council [online]. Available at: <www.atlanticcouncil.org/about/board-of-directors/> [Accessed 20 November 2020].

Boyd-Barrett, O., 2016. Western Mainstream Media and the Ukraine Crisis: A Study in Conflict Propaganda. London: Routledge.

Bush, S.S., 2019. National Perspectives and Quantitative Datasets. Journal of Global Security Studies, 4(3).

Colgan, Jeff D, 2019a. American Perspectives and Blind Spots on World Politics. Journal of Global Security Studies, 4(3).

Colgan, Jeff D, 2019b. American Bias in Global Security Studies Data. Journal of Global Security Studies, 4(3).

Colton, T.J., and Charap, S., 2017. Everyone Loses: The Ukraine Crisis and the Ruinous Contest for Post-Soviet Eurasia. London: Routledge.

Cooley, A., and Snyder, J. (eds.), 2015. Ranking the World: Grading States as a Tool of Global Governance. Cambridge University Press.

Czolij, E., 2020. Putin Woos Trump with WWII Nostalgia, but Russia’s Hybrid War Continues. The Atlantic Council, 7 May.

Dalby, S., 1988. Geopolitical Discourse: The Soviet Union as Other. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 13 October.

Dickinson, P., 2016. Europe Still in Denial as Russia Ushers In the Age of Hybrid Hostilities. The Atlantic Council, 31 May.

Dickinson, P., 2017. Why Did Putting Get Stuck in Eastern Ukraine? The Atlantic Council, 4 October.

Dickinson, P., 2018a. Reluctant Russophobes: The Underwhelming International Response to Putin’s Hybrid War. The Atlantic Council, 4 March.

Dickinson, P., 2018b. From Crimea to Salisbury: Time to Acknowledge Putin’s Global Hybrid War. The Atlantic Council, 13 March.

Dickinson, P., 2019. Whoever Wins Ukraine’s Presidential Race, Russia Has Already Lost. The Atlantic Council, 29 March.

Drezner, D., 2017. The Ideas Industry. New York: Oxford University Press.

Driscoll, J., 2019. Ukraine’s Civil War: Would Accepting This Terminology Help Resolve the Conflict? PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, No. 572, February.

Foglesong, D., 2007. The American Mission and the ‘Evil Empire’: The Crusade for a ‘Free Russia’ since 1881. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Friedman, O., 2018. Russian “Hybrid Warfare.” New York: Oxford University Press.

Forsyth, R., 2016. Russia’s Hybrid Warfare Is Harming Germany. The Atlantic Council, 12 May.

Galeotti, M., 2015. Gaps in NATO Hybrid Defense. The Atlantic Council, 30 July.

Gaufman, L., 2017. Security Threat and Public Perceptions: Digital Russia and the Ukraine Crisis. London: Palgrave.

Gerasymchuk, S., 2015. Frozen Conflict in Moldova’s Transnistria: A Fitting Analogy to Ukraine’s Hybrid War? The Atlantic Council, 1 September.

Goncharenko, O., 2020. The Lesson of Crimea: Appeasement Never Works. The Atlantic Council, 27 February.

Gorenburg, D., 2019. Circumstances Have Changed Since 1991, but Russia’s Core Foreign Policy Goals Have Not. PONARS, January.

Grove, T., and Cullison, A., 2019. Ukraine Company’s Campaign to Burnish Its Image Stretched Beyond Hunter Biden. The Wall Street Journal, 7 November.

Gzirian, R., 2015. Russia’s Buildup Along Ukraine’s Border Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Does. The Atlantic Council, 11 June.

Herbst, J., 2017. Should the U.S. Arm Ukraine? For the Answer, Look to the Soviet-Afghan War. The Atlantic Council, 9 May.

Hobson, J.M., 2012. The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inayatullah, N., and Blaney, D.L., 2004. International Relations and the Problem of Difference. London: Routledge.

Interfax 2019. Minyust vnyos “Atlantichesky sovet” v spisok nezhelatel’nykh [Ministry of Justice Included the Atlantic Council into the List of Undesirable Organizations]. Interfax, 29 July.

Kanet, R., (ed.), 2017. The Russian Challenge to the European Security Environment. New York: Palgrave.

Kararnycky, A., 2020. Prisoner Exchange Lifts the Veil on Russia’s Hybrid War Against Ukraine. The Atlantic Council, 9 January.

Kempe, F., 2019. How the U.S.-European Alliance Can Become Even Stronger in an Era of Disruption. CNBC, 14 February.

Kofman, M., 2016. Russian Hybrid Warfare and Other Dark Arts. War on the Rocks, 11 March.

Kofman, M., 2020. Russia’s Armed Forces under Gerasimov, the Man without a Doctrine. Russian Military Analysis, 1 April [online]. Available at: <russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/2020/04/02/russias-armed-forces-under-gerasimov-the-man-without-a-doctrine/> [Accessed 20 November 2020].

Kols, R., 2018. Nato Must Meet Russia’s Hybrid Warfare Challenge. The Atlantic Council, 7 March.

Kudelia, S., 2014. Domestic Sources of the Donbas Insurgency. PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, No. 351, September.

Levin, D.H., Trager, R., 2019. Things You Can See from There You Can’t See from Here. Journal of Global Security Studies, 4(3).

McFaul, M., 2014. Moscow’s Choice. Foreign Affairs, November/December.

Mearsheimer, J., 2014. Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault. Foreign Affairs, September/October.

Mearsheimer, J. 2011. Why Leaders Lye: The Truth about Lying in International Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Media Bias/Fact Check, 2020. Atlantic Council. https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/atlantic-council/ Retrieved on July 6.

Medvetz, T., 2012. Think Tanks in America. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Monaghan, A., 2016. Putin’s Way of War The ‘War’ in Russia’s ‘Hybrid Warfare’. Parameters 45(4), Winter.

Montgomery, M. 2017. Post-Truth Politics?: Authenticity, Populism and the Electoral Discourses of Donald Trump. Journal of Language and Politics.

NATO’s Counter. 2019. NATO’s Counter to Russian Hybrid Warfare. NATO/The Atlantic Council, 17 June.

Nichols, T., 2017. How America Lost Faith in Expertise. Foreign Affairs, 96(2), March/April.

Oren, I., 2002. Our Enemy and U.S.: America’s Rivalries and the Making of Political Science. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Orenstein, M.A., 2018. The Lands in Between: Russia vs. the West and the New Politics of Hybrid War. New York: Oxford University Press.

Our Mission, 2020. [online]. Available at: <www.atlanticcouncil.org/about/> [Accessed 20 November 2020].

Poliakova, A., 2017. Trump’s Budget Cuts Seen as Detrimental to U.S. Effort to Fight Russian Propaganda. The Atlantic Council, 30 June.

Pomerantsev, P., 2014. Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible. New York: Public Affairs.

Porter, P., 2018. Why America’s Grand Strategy Has Not Changed. International Security, 42(4).

Posen, B.R., 2013. Pull Back. Foreign Affairs, January/February.

Putin, V., 2020. The Real Lessons of the 75th Anniversary of World War II. The National Interest, 18 June.

Pynnöniemi, K. and Jokela, M., 2020. Perceptions of Hybrid War in Russia: Means, Targets and Objectives Identified in the Russian Debate. Cambridge Review of International Affairs. DOI: 10.1080/09557571.2020.1787949.

Renz, B., 2018. Russia’s Military Revival. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Reznikov, O., 2020. To Stop Putin, the Western World Must Revisit the 1994 Budapest Memorandum. The Atlantic Council, 31 May.

Rumer, E., 2019. The Primakov (Not Gerasimov) Doctrine in Action. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 5 June.

Salas-Porras, A. and Murray, G. (eds.), 2017. Think Tanks and Global Politics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Said, E.W., 1993. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Sakwa, R., 2016. Frontline Ukraine. Crisis in the Borderlands. London: I. B. Tauris.

Sestanovich, S., 2014. How the West Has Won. Foreign Affairs, November/December.

Simons, G., 2010. Mass Media and Modern Warfare: Reporting on the Russian War on Terrorism. London: Routledge.

Small, M., 1998. The Atlantic Council—The Early Years. Prepared for NATO as a report related to a Research Fellowship, 1 June [pdf]. Available at: <www.nato.int/acad/fellow/96-98/small.pdf> [Accessed 20 November 2020].

Sokov, N., 2020. Teper’ ya zhaleyu, chto vvyol etot termin v shiroky oborot [Now I Regret Putting this Term into Wide Circulation]. Kommersant, 15 July.

Tokariuk, O., 2019. The Most Outrageous Case This Summer That No One Has Heard of. The Atlantic Council, 1 August.

Turton, H.L., 2015. International Relations and American Dominance. London: Routledge.

Tsygankov, A., 2009. Russophobia: The Anti-Russian Lobby and the American Foreign Policy. New York: Palgrave.

Tsygankov, A. and Parker, D., 2015. The Securitization of Democracy. European Security, 24(1).

Umland, A., 2016. Russia’s Pernicious Hybrid War against Ukraine. The Atlantic Council, 22 February.

Vitalis, R., 2015. White World Order, Black Power Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Vrabel, F., Janda, J., and Vichova, V., 2016. How Russian Propaganda Portrays European Leaders. The Atlantic Council, 16 August.

Walt, S.M., 2018. The Hell of Good Intentions. New York.

Wigell, M., 2019. Democratic Deterrence. Finnish Institute of International Affairs, Working Paper # 110, September.

Wither, J.K., 2016. Making Sense of Hybrid Warfare. Connections QJ, 15(2).

Yelchenko, V., 2020. Putin’s Russia Has Weaponized World War II. The Atlantic Council, 12 May.

Zhukov, Y.M., 2017. Warfare in a Post-Truth World: Lessons from Ukraine. PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, No. 471, April.

***

[1] Galeotti later publicly regretted his own inadvertent contribution to it (for details see: Kofman, 2020). The notion of HW is not the only one misinterpreted by experts and politicians to serve their needs. The idea of “escalation for de-escalation” has been developed in a similar way (Sokov, 2020).

[2] For a full list of donors in 2019, see: www.atlanticcouncil.org/support the council/honor-roll-of-contributors-2019/