Soft power swiftly reappeared in Russia’s foreign policy in the summer of 2020. On June 25, 2020, journalist Yevgeny Primakov was appointed the new head of Rossotrudnichestvo, the main Russian soft power agency. Although skeptical of the term itself, he actively called for an overhaul of this segment of Russian foreign policy. His upgrade program caused a wide response in the expert community, where the Russian approach to soft power was under constant fire as some thought it was too soft while others considered it to be too tough.

By that time a number of leading Russian international relations experts had already become disillusioned with soft power. For example, Sergei Karaganov (2019) wrote that the soft power concept should be recognized as an intellectual delusion as it was not “adequate” to the new reality of international relations any more, and Fyodor Lukyanov (2016) pointed out that soft power no longer retained the effectiveness that was expected of it at the end of the twentieth century, since at one point it had used to “reflect a very special moment in the development of the international system,” when the West needed to prove to itself and the world the accomplishment of historical justice at the end of the Cold War. The term has almost completely been dropped by Russian International Affairs Council Director Andrei Kortunov. Moreover, the foreign expert community has long denied the Russian strategy any “softness.” In fact, the author of the soft power concept, Joseph Nye (2018), has consistently criticized the Russian model, referring to it as “sharp power.”

At the same time, soft power has been one of the most popular topics with the Russian expert and academic community over the past twenty years. Since 2006, following the publication of the first article by Vadim Kononenko titled “Creating an Image of Russia?” (2006), interest in this topic soared steadily, climaxing in 2013-2014. It is noteworthy that soft power was actively discussed in Russia in Global Affairs and was at the peak of popularity in 2014, when relations between Russia and the West became as strained as never before. This means that, despite Russia’s acute conflict with Western partners, leading Russian experts believed, on the one hand, in the effectiveness of soft power as a foreign policy instrument (Ukraine was often considered an example of its effectiveness), and on the other hand, they nevertheless counted on the possibility of dialogue and the power of persuasion between the conflicting parties.

For the first time Russian soft power became a subject of discussion at the highest political level in 2007, when at a meeting of the Russian Public Chamber Council members with Vladimir Putin, Vyacheslav Nikonov said that Russia “needs… a national project to create its own soft power instruments” (Nikonov, 2007). Since then, it has gone a long way from a decentralized model, very close to Nye’s original concept, to a hybrid approach designed, on the one hand, to ensure self-defense, and on the other hand, to launch a counterattack as part of information warfare.

Over the years, it has gone through three clearly defined stages: 1) the unofficial stage, or the rise (2000-2007/2008) 2) institutionalization (2007/2008 — 2013/2014), and 3) the tightening of the approach, or the fall (since 2013/2014).

There are grounds to believe that with the appointment of Yevgeny Primakov, as Tatyana Poloskova has aptly noted (2020), Russian soft power has received the “last chance.” So, it is now important to analyze the way traveled, understand what decisions were successful, what internal and external factors mattered and, most importantly, what results the chosen strategy has produced. In our article, we will for the first time attempt to periodize the evolution of the Russian soft power strategy, thereby trying to find answers to the questions raised above.

STAGE 1. INFORMAL STAGE, OR THE RISE

(2000 — 2007/2008)

The first stage in the development of Russia’s soft power model coincided with the period of Moscow’s growing foreign policy activity in the 2000s. At that time, not only did the government not have a separate strategy, but even the Kremlin walls had not yet heard the unusual word combination “soft power.” But it was precisely in the 2000s that despite (or maybe thanks to) decentralization and fragmentation of actions Russian soft power was the “softest” and therefore the most effective.

Governmental agencies started to take concrete steps to improve the image of Russia in the world after Vladimir Putin had so instructed Russian diplomats in June 2004. At that time, soft power projects pursued mainly economic goals. The organization of forums and expert platforms, PR campaigns, and even work with compatriots sought to advance the interests of major Russian companies and the Russian economy (mainly exports) as a whole.

So, in 2005 the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum acquired the status of “presidential” (because it was attended by the President of Russia), and official cooperation with the World Economic Forum in Davos began in 2007. Significant bilateral projects were launched, in which economic issues played a major role: the Russian-German Petersburg Dialogue (initiated in 2001 by Vladimir Putin and Gerhard Schroeder), the Franco-Russian Dialogue (inaugurated in 2004 under the patronage of Vladimir Putin and Jacques Chirac), the Russian-American Council for Business Cooperation (created in 2000 at the suggestion of the Foreign Ministry; since 2009 it has been working under the umbrella of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs), etc.

The launch of the Valdai International Discussion Club in 2004 became an important step in promoting Russian interests abroad. At the initial stage, despite the participation of the Russian leader, it was just an informal expert forum attended by a wide range of specialists (sometimes with diametrically opposite views) and intended to “tell the world about Russia.” The participants included Michael McFaul, Fiona Hill, Nikolai Zlobin, Boris Nemtsov, Leonid Gozman, Vladislav Inozemtsev, Alexander Dugin, Alexander Prokhanov, Sergei Guriev, and Sergei Glazyev.

Among the forums of that time, standing out was the Rhodes Forum, which was held as part of the Dialogue of Civilizations international program, launched in 2002 on the initiative of Vladimir Yakunin (Russia), Jagdish Kapur (India), and Nicholas Papanicolaou (Greece). From the very beginning the Dialogue of Civilizations had a strong ideological slant. Its goal was to oppose the unipolar world (that is, the United States) and promote an alternative “civilizational project,” in which each civilization had the right of voice and the right to its own social, cultural, and religious model. At the same time, the forum was presented as a completely independent and unbiased public project, which “has not been established by the state, is not a political movement and does not have to fulfill anyone’s plan.” However, senior Russian officials regularly attended the forum, thus emphasizing its importance for Russian foreign policy.

At about the same time, Russia began to actively integrate into the international media market. In 2005, the Russian international television channel Russia Today went on line. Its declared purpose was to provide more objective information about modern Russia and its position on international political issues. In 2007, Russia Beyond the Headlines (RBTH)—an international supplement to Rossiyskaya Gazeta—was established. It appeared (until 2017) in 27 leading foreign publications and was available in 21 countries in 16 languages. Its total circulation had reached approximately 10.5 million copies, with a readership of some 32 million (Ageeva, 2016). In parallel, the largest international PR agencies—Ketchum, the Washington Group (based in the U.S.) and GPlus Europe (based in Belgium)—were hired (Chitty et al, 2017). The main results of cooperation with them were the successful G8 Summit in St. Petersburg in 2006, the promotion of Putin for the title of Person of the Year in the Time magazine in 2007, the subsequent release of the four-episode documentary “Putin, Russia and the West” on BBC Two in 2012, and the publication of Putin’s article “A Plea for Caution from Russia” in the New York Times in 2013, in which he warned the United States against intervening in Syria and getting carried away with its own exclusivity and the role of “world judge.” The PR campaign of the Sochi Olympics in 2014 was also organized by Ketchum. In 2006, the agency received the prestigious Silver Anvil Prize from the Public Relations Society of America and the PRWeek Global Campaign of the Year Award for its work.

In addition, active work was underway with foreign lobbyists: Henry Kissinger, James Baker, Thomas Graham (U.S.), Gerhard Schroeder (Germany), Bernard Volker (France). Their services were primarily used to promote Russian companies such as Gazprom, Transneft, and Rosneft, but not only that. For example, Thomas Graham (Kissinger Associates) presented a report in the White House in 2009 which harshly criticized Mikhail Saakashvili’s actions during the 2008 Russian-Georgian war and advised the government not to push for NATO expansion, but instead to support Dmitry Medvedev’s proposals for a new security system in Europe (Van Herpen, 2016, p. 71).

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, active work began with the Russian diaspora abroad. While in Soviet times emigrants were branded exclusively as traitors, in the new Russia the Russians abroad began to be viewed as a related socio-cultural world, a peripheral source of Russianness which could help expand the sphere of influence and strengthen the country’s position in the international arena (Batanova, 2009). Political strategists Pyotr Shchedrovitsky and Gleb Pavlovsky proposed a business-oriented approach to the Russian diaspora. According to this approach, compatriots living abroad were to be considered part of Russian soft power: by working and studying in foreign countries, they could act as natural guides for Russian culture and as effective intermediaries in economic projects. During that period, a number of important steps were taken to organize official interaction with the Russian diaspora: a relevant law and a government program were adopted. The Kremlin’s actions were harmoniously combined with grassroots initiatives, including those by the Moscow City Hall and a number of NGOs.

It was at that time that the Russian Orthodox Church began to contribute actively to the implementation of Russian soft power projects. At the initial stage, its actions were more independent, although even then one could detect signs of a foreign policy “symphony” with the Kremlin (Van Herpen, 2019). The Russian Orthodox Church was an active participant in the events organized as part of the Valdai Club and the Dialogue of Civilizations program, and in 2008, with the assistance of the Russian Foreign Ministry, Metropolitan Kirill (Gundyaev) addressed a meeting of the UN Human Rights Council. But perhaps the most important achievement of the Russian Orthodox Church in the 2000s was its reunification with the Russian Church abroad, which became possible thanks to the efforts of the Russian government and, in particular, Vladimir Putin (Konygina, 2007). The reunification of the Russian Orthodox Church with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia took place on May 18, 2007 and had a tremendous international impact, including in terms of soft power. This gave the Russian Orthodox Church control over churches and other related real estate, as well as, which is particularly important, influence on Orthodox communities in different countries around the world.

All of the above leads us to the first obvious conclusion about the characteristics of the initial stage in the development of Russian soft power. Firstly, it was an informal approach, with no strict control by the state, but with pluralism in formats and personalities, private initiatives, and the involvement of foreign specialists (especially in the field of PR).

At that time, there was no general strategy, but the state considered all initiatives important, including semi-public, private and informal ones, if they could help improve the Russian image.

The second important characteristic is the non-confrontational nature of the Russian approach. It was not the result of the ideological vacuum created after the collapse of the USSR. During its rise, Russian soft power followed the Western discourse on human rights, the rule of law, and democracy. Russia’s international image and foreign policy narrative were based on Western values. At first, Russia positioned itself as a young democracy, and a little later as a “sovereign” democracy, that is, a kind of democracy that was not a copy of the Western one, but still was a democracy. The PR-agency Ketchum considered a change in global public opinion about Russia and recognition of its democratic nature its main achievement (Van Herpen, 2016, p.71).

Russia sought to take its place in the international debate on human rights and democracy by establishing the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation in 2007, with offices in Paris and New York. Andranik Migranyan, director of its U.S. branch, saw the Institute’s mission in forging a dialogue with American society and explaining the Russian position on human rights and democracy. The same logic was used when the Russian Foreign Ministry helped organize Metropolitan Kirill’s speech at a meeting of the UN Human Rights Council in 2008. On the one hand, the metropolitan spoke about human rights, but on the other hand, he made it clear that there was no single correct interpretation of human rights and stressed the need to harmonize all interpretations with local traditions and religions.

The first informal stage of Russian soft power can be regarded as its rise, since during this period it worked exactly as it was conceived by its author, Joseph Nye. As the original concept suggests, soft power was realized by NGOs and civil society, without comprehensive state control, it involved highly qualified (albeit foreign) specialists in the field of PR, used the language of human rights and democracy accepted in the West, and created a sense of common cultural and legal space with the West (the target audience was mainly Western countries).

The line under the first period in the development of Russian soft power was drawn up by the Russian-Georgian conflict in August 2008. It was then that the Russian leadership faced a wall of misunderstanding among foreign media, political leaders, and the public. After the heat had subsided, the Kremlin analyzed its own media mistakes. For example, as a result of Duma speaker Boris Gryzlov’s total ban on communication with foreign media (Gabuev and Tarasenko, 2012) and the position of Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov—“we will not replace real work with PR campaigns,” the Russian position on the conflict was not covered by foreign media and the Western community heard only Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili’s point of view. Based on this analysis, the Russian government decided to strengthen the Russian soft power strategy.

STAGE 2. INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF RUSSIAN SOFT POWER

(2007/2008 — 2013/2014)

In 2007-2008 Russian soft power entered a new stage of its development. Putin’s speech at the Munich Security Conference marked a transition to a tougher and more independent foreign policy, while the media fiasco during the conflict with Georgia forced the Russian authorities to pay more attention to soft power. From then on, Russian soft power began to develop as a separate strategy with its own institutions and centers under strict government control.

This is when soft power became part of the official discourse and was regularly mentioned by Russian top officials such as Dmitry Medvedev, Sergei Lavrov, Vyacheslav Nikonov, and others. In February 2012, Putin placed special emphasis on soft power in his election article “Russia and the Changing World” (Putin, 2012), mentioning both its positive and negative aspects. He used this approach later as well: in 2011-2014 he systematically talked about soft power, but differently in different situations. At meetings with diplomats and broader circles, he spoke about it as an important new tool for international cooperation, and at meetings with law enforcers he referred to it as “instruments of pressure” (Putin, 2013a), “special operations” (Putin, 2013b), and “well-known techniques (to) weaken Russia’s influence” (Putin, 2013c) (the latter vision became more pronounced in 2013). And yet, a new Foreign Policy Concept devised in November 2013 included soft power as an official instrument of the Russian strategy in the international arena. It said in particular that Russia would be “improving the application of soft power and identifying the best forms of activities in this respect… further developing the regulatory framework in the above-mentioned area” (MFA, 2013). When the Concept was updated in 2016, soft power remained in the document as one of the aspects of Russian Foreign Ministry’s work (MFA, 2016).

In addition to acquiring official status in Russia’s foreign policy strategy, soft power became gradually institutionalized. In 2008, the Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States, Compatriots Living Abroad and International Humanitarian Cooperation (Rossotrudnichestvo) was created on the basis of Roszarubezhtsentr, which, in turn, had succeeded the Union of Soviet Friendship Societies. Its main tasks included implementing the state policy of international humanitarian cooperation and promoting the consolidation of the post-Soviet space through exchange programs, education, and the study of the Russian language and culture. Rossotrudnichestvo consistently created a network of its representative offices abroad (following the example of Alliance Française, British Council, and Goethe-Institut)—Russian centers of science and cooperation. There are currently 97 of them (73 centers and 25 representatives at Russian embassies).

At the same time, following the American model, the Russian government began to establish soft power public organizations and finance various NGOs working abroad. The Institute for Democracy and Cooperation was the first. In the same year 2007, the Russkiy Mir Foundation (literally Russian World Foundation) was established by a presidential decree. The Foundation was tasked with popularizing the Russian language and culture, uniting compatriots living abroad, and creating a network of NGOs working in the same areas abroad through grants. Like Rossotrudnichestvo, the Russkiy Mir Foundation started to open its representative offices abroad, mainly at universities and schools. Its representation was often reduced to just a “Russkiy Mir room” featuring books in Russian and booklets about the Foundation. In total, there are 97 centers and 123 Russkiy Mir rooms today. One of the results of the Foundation’s work was the creation of a catalog of foreign NGOs which were engaged in the promotion of the Russian language and culture and considered themselves part of the Russian world. Its central event is the Assembly of Russian compatriots living abroad, which has been held every year since 2007. It brings together about 800 participants, including Russian top officials and high-ranking representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church as guests of honor.

During the period of institutionalization, a number of state structures were created to work with compatriots: the World Coordinating Council of Russian Compatriots was created in 2009 (it united coordinating councils that had functioned separately abroad since 2006), the Fund for Supporting and Protecting the Rights of Compatriots Living Abroad was established in 2012 (founded by the Russian Foreign Ministry and Rossotrudnichestvo), and the World Russian Press Foundation was instituted in 2012.

The Russian Orthodox Church actively collaborated with Russian soft power institutions, especially in interacting with compatriots and promoting the idea of the Russian world. Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev) was included in the Foundation’s Board of Trustees, and church hierarchs regularly attended its events. Russian Orthodox Church leaders always participated in the World Congresses of Compatriots.

Since the formation of the global agenda is also an instrument of soft power (Nye, 2011, pp.20-21), in 2010-2011 the Russian government took a number of successive steps to create its own intellectual and expert centers designed to promote Russian analytics on international relations and Russian foreign policy, including in the English-language segment of the Internet. In 2010, the Russian president ordered the creation of the Russian International Affairs Council, later in the same year the Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Fund was established, and a year after that the work of the Valdai Club was formalized by creating the Valdai International Discussion Club Development and Support Fund.

International relations have never been a neutral academic discipline, and “theoretical models and concepts, especially if their authors are representatives of influential countries, have considerable potential and can be an instrument in the soft power arsenal to promote foreign policy interests” (Tsygankov, 2013).

In addition, in 2011 Russia began publishing its own reports on the human rights situation in foreign countries (mainly in the U.S., Canada, European countries, and Ukraine). These reports issued by the Russian Foreign Ministry appeared as a response to similar investigations by Western organizations against Russia rather than independent unbiased studies. Nevertheless, by publishing these reports Russia continued to participate in international debates, thereby recognizing, at least formally, the importance of human rights and democracy as they were understood in the West.

It is worth noting that by that time Russia had already quite actively used the rhetoric, and practice, of retaliatory steps, without formally going beyond the framework of Western discourse. The abovementioned Institute for Democracy and Cooperation was founded on Putin’s personal instructions. Speaking at the Russia-EU summit in Lisbon in October 2007, Putin said, in particular, that “the European Union, with the help of grants, helps to develop institutions of this kind in Russia” and that “the time has come when the Russian Federation can do the same in the European Union” (Grigoryeva, 2007).

The international television channel Russia Today also stepped up its activity. After the media failure in covering the Russian-Georgian conflict in 2008, the Russian government had realized the importance of media support for foreign policy and provided funds and specialists for strengthening Russia Today. In 2009, the word “Russia” was removed from the channel’s name and it began to operate under a more neutral brand, RT, which was not affiliated with the Kremlin. In the same year, the channel opened a Twitter account and launched its Spanish-language television version.

It is noteworthy that during that period RT had not yet made scandalous popularity an alpha and omega of its strategy. At that time, RT rather used technologies generally adopted in the media space, including cooperation with renowned presenters and activists such as WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange or legendary American journalist Larry King, who allowed his show to be broadcast on RT (Chakelyan, 2015).

At the same time, the channel began to gravitate towards conspiracy theory, which invariably attracted a certain part of the foreign audience (Yablokov, 2015). In general, until 2013, RT attracted viewers with neutral content. According to a study by Daily Beast, 80% of RT’s most popular programs focused on emergencies, such as natural disasters (Zavadski, 2015). RT did not resort to shocking campaigns so often. The situation began to change in 2012, when RT started covering the civil war in Syria: after reports from Damascus, the British regulator Ofcom issued warnings almost annually and fined the channel for bias and political prejudice.

The second stage in the development of soft power and its entire history reached its peak during the XXII Olympic Winter Games in Sochi in February 2014. On the one hand, the Olympics became the Kremlin’s political success, and on the other hand, an example of real soft power as it allowed the achievements of modern Russia to be seen not only by thousands of guests in Sochi, but also by millions of television viewers around the world. As the New York Times wrote on February 23, 2014, the closing ceremony of the XXII Olympic Winter Games in Sochi “provided a showcase of Russia’s many success stories, and like it or not, hosting an Olympics is now among them” (Makur, 2014). However, the triumph of soft power did not last even a month and in March 2014 it ran dry, giving way to tough “manly” talk (Borisova, 2015).

So, the main characteristic of the second stage in the development of Russian soft power is its institutionalization and formalization. While at the first stage soft power was rather a combination of both public and government initiatives (which were often implemented informally), at the second stage almost all of these initiatives turned into government or para-government institutions (funds, NGOs, think tanks, coordinating councils), which were responsible for the implementation of one or several soft power projects. It was this total “governmentalization” that Joseph Nye considered the biggest mistake of the Russian soft power strategy (Nye, 2013).

The period of institutionalization was not ideologically neutral, and this is its second important feature. In 2007-2014, the Russian official soft power discourse was still built around political values, such as human rights and democracy. Offices of the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation worked actively in Paris and New York, the Foreign Ministry regularly published White Papers on human rights violations in the United States and Europe, and top government officials and the Foreign Ministry did not officially mention any major differences between the Russian and Western value systems. Rossotrudnichestvo head Konstantin Kosachev argued in 2012-2014 that the basic principles of democracy, human rights and freedoms, which are enshrined in the UN Charter, as well as conventions and treaties could not be considered anyone’s property, for example, the West’s, or an individual characteristic of someone’s soft power, and that “freedom, democracy, lawfulness, social stability, and respect for human rights have become ‘the consumer goods basket’ of the modern world, which everyone would like to have.” Therefore, “any idea rejecting this standard 21st-century set of values would certainly fail to stand.” In one of his articles on soft power, Kosachev wrote that “the task of presenting national tradition should not be at odds with the universally recognized human rights, and norms and principles of international law that protects the basic democratic standards of the 21st century” (Kosachev, 2012). He suggested filling Russian soft power with positive content, which should rest on three pillars: cooperation, security, and sovereignty. In his opinion, Russian know-how in international relations could be an approach whose main elements were respect for the sovereignty of partners and cooperation without any preconditions (Kosachev, 2013). But this concept never materialized: after 2014, during the third stage, the Russian government chose another narrative, which constituted the ideological content of Russian soft power.

A new topic was joint opposition to attempts to rehabilitate fascism and the preservation of the memory of the common sacrifices made by Russia and Western countries in the name of peace during World War II. The year 2005, the 60th anniversary of the victory in that war, marked the beginning of this strategy. In addition to a big military parade in Red Square, which was attended by many world leaders (American President George W. Bush, German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, French President Jacques Chirac, Chinese President Hu Jintao, etc.), Vladimir Putin published an article in the French Figaro titled “Lessons of the Victory over Nazism: Through Understanding the Past Towards the Joint Construction of a Safe Humane Future,” and gave a joint interview with Schroeder on the same topic to Bild (Senyavsky and Senyavskaya, 2009). From this moment on, Russia regularly initiated roundtables, conferences, and international meetings on the lessons of the Second World War. This was one of the central topics in the activities of Russian soft power institutions. In addition, a number of international organizations and movements were created, for example We Are the Heirs of the Victory and Peace against Nazism. While the former was mainly aimed at the CIS countries and Russian compatriots, the latter was a serious attempt to unite a wide range of foreign organizations on this topic, if not around Russia, then with it. Over time, however, its activities died down, and the common memory of World War II became extremely politicized and ended up on the battlefields of information warfare.

STAGE 3. THE TIGHTENING OF RUSSIAN SOFT POWER, OR FALL

(since 2013/2014)

The tightening of Russian foreign policy is usually believed to have begun in 2007 when Putin delivered his speech at the Munich Security Conference. However, it was followed by Medvedev’s presidency, which began with a conflict with Georgia, but otherwise was generally peaceful and aimed at cooperation with Western partners. The Russian regime began to gradually close up and assume the “besieged fortress” attitude in 2012. The fall of the Libyan regime in 2011, accompanied by the massacre of the country’s long-term leader Muammar al-Gaddafi, and the intensification of protest movement in Russia itself in 2011-2012 increased the Russian political elite’s fears of color revolutions (Zygar, 2016). The defeat in the confrontation with pro-Western forces during Maidan protests in Kiev and the loss of Ukraine ultimately led to an irreversible transformation of the political regime in Russia, which prioritized protection against alleged external interference.

An event of historical magnitude that took place in March 2014 changed the map of Europe when the Crimean Peninsula became part of Russia. This was followed by a period of fierce confrontation between Russia and the West, which experts even called a new Cold War. Russian foreign policy went into permanent “defensive-offensive” mode, and the same approach was applied to the soft power strategy.

The strategy retained the same set of instruments, but their content and modus operandi changed drastically. This was most clearly manifested in the Russian media working for the foreign audience. RT and the Internet media outlet Sputnik (created in November 2014) began to employ more aggressive rhetoric and journalistic techniques: RT Editor-in-Chief Margarita Simonyan later admitted that the channel worked in combat-like conditions amid a war being waged against Russia (Porubova and Anufrieva, 2020). In addition to provocative headlines and controversial interpretations of events both in Russia and the world, both media sometimes resorted to replicating unverified or even deliberately false information (the story about 400 American mercenaries in Ukraine in May 2014 (The Insider, 2017), an incident with teenage girl Lisa in Germany 2016 (Rutenberg, 2017), an attempt to stage a migrant fight in Sweden in 2017 (Kramer, 2017), which was also linked to the Russian television channel, and others). Obviously, RT’s strategy became clearly offensive during that period: in addition to escalating anti-American and anti-Western sentiments, the channel focused on European and American sore sports, trying to pay more attention to issues that divided European societies, thereby polarizing them as much as possible.

Investigations were regularly conducted against RT by the media regulator in the UK, and security services in France (CAPS & IRSEM, 2018) and Estonia (2018). RT became a subject of tough conversation between Vladimir Putin and French President Emmanuel Macron during their first meeting in Versailles in May 2017. Macron then claimed that the Russian channel’s work did not conform to the principles of journalism. In the end, RT has gained a steady reputation as an alternative channel for a narrowly marginalized audience in Europe and the U.S. (Limonier and Audinet 2017).

The changes also affected interaction with the Russian diaspora abroad. The “Crimean issue” divided it completely. On the one hand, the Letter of Solidarity with Russia at the Time of the Ukrainian Tragedy, published in December 2014 by prominent Russian emigres (mainly those who left the country after the 1917 revolution), can be considered an undeniable success of Russian diplomacy (RG, 2014). On the other hand, a letter from the other part of the same “old” emigration strongly condemned Russia’s actions in Ukraine (von Gan, 2014), thus clearly indicating maximum polarization of the Russian diaspora. Vladimir Yakovlev, the founder of the Kommersant Publishing House and Snob magazine, later wrote that March 2014 had destroyed the phenomenon of Global Russians, meaning those who were the bearers of Russian culture, maintained ties with Russia and could live in different countries of the world, absorb their culture and become part of any community. Yakovlev was thus referring to the radical rejection by part of Russian emigrants of the policy chosen by the Kremlin, and to their refusal to continue any interaction with it in the future (Yakovlev, 2017).

The idea of the Russian world, which since the 2000s has been actively promoted by both the Russian government and the Russian Orthodox Church, has also transformed significantly from a purely cultural into a geopolitical phenomenon, forfeiting the potential of a neutral concept that could unite all those who, regardless of nationality, are interested in Russian culture and are “not indifferent to its affairs and fate” (Batanova, 2009, p.14). After the term was used in official rhetoric explaining Russian actions in Crimea in the spring of 2014, the Russian world narrowed considerably, with Ukraine having been forced out of it and the remaining allies having learned their lesson from the Crimean story (Lenta.ru, 2015). The politicization and securitization of this idea has made it utterly impossible to use it as an instrument of soft power that could unite the Russophiles regardless of their political beliefs.

During the period of “tightening,” Russia continued to employ other soft power instruments which were in use since the first stage. These include the work of expert centers, the enrollment of foreign students in Russian universities, cultural projects, and support for the study of the Russian language. The new strategy has affected them to a lesser extent (with the exception of the Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Fund, which has been engaged in the information and expert war).

Active promotion of the conservative narrative has become a new track of Russian foreign policy. Starting in 2013, Russia began to try on the role of a conservative power and the “last stronghold” of traditional values in the world. Speaking at the opening of a Valdai International Discussion Club conference in September 2013, Putin said that Western countries “have renounced their roots, including Christian values, and they are implementing policies that equate large families with same-sex partnerships, belief in God with the belief in Satan,” while “people in many European countries are embarrassed or afraid to talk about their religious affiliations” (Putin, 2013d). He continued this narrative in December of the same year in an Address to the Federal Assembly, stating: “Today, many nations are revising their moral values and ethical norms, eroding ethnic traditions and differences between peoples and cultures,” which leads to “destruction of traditional values from above.” Putin expressed confidence that many like-minded people would join Russia in the struggle for the preservation of traditional values. A report released by the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy in 2016 said that Russia’s new soft power strategy was based on a set of values “inherited from the past,” such as “political and cultural pluralism and the freedom of choice instead of Western universalism” (SVOP, 2016, p. 16).

The implementation of the new strategy required new tools and techniques. These include cooperation with ultra-right parties in Europe and conservative organizations abroad. They met with the Russian leadership, traveled to Crimea, and received indirect funding and information support (National Assembly (France), Lega Nord (Italy), Swedish Democrats, etc.), and even attended major international events (a forum in St. Petersburg in 2015). Russian laws to counter the propaganda of homosexuality among young people, as well as the adoption of amendments to the Constitution which define a marriage as a union of a man and a woman, were designed to show Russia’s commitment to traditional values not only to the domestic audience, but also to the whole world.

A separate issue is the substance of Russian conservatism and its role in modern Russian society. In addition to the obvious traditional (at the same time homophobic) angle, which implies the preservation of traditions, in particular the family, it clearly expresses the ideas of statism and the importance of the national leader. But do Russian society and the elite share these values? While statist feelings are quite strong in Russian society (Engel, 2019), it is not quite so with faith and family values. According to statistics, about 4-8% of Russians go to church regularly and participate in sacraments (Faith Index, 2017), while one in two marriages ends in divorce (Yeryomina, 2017), and six (out of seventeen) million Russian families are incomplete (Deryomina, 2017).

Experts point out that Russian conservatism has certain potential as soft power (Petro, 2015; Robinson 2020).

As Fyodor Lukyanov (2013) has rightly pointed out, such a controversial version of conservative ideology may attract a certain contingent, but “it will be an extremely specific assortment from the European ultra-right to the Middle East Islamists.”

Another area of the Kremlin’s soft power work, which has become particularly important during the period of tightening, is the use of so-called geopolitical businessmen for foreign policy purposes. Russia’s soft power already utilized these possibilities in 2010-2011 (for example, the purchase of the newspapers Evening Standard and The Independent (UK) by Alexander Lebedev and the newspaper France-Soir by Sergei Pugachev (Van Herpen, 2016, p. 108)), but their role increased dramatically when traditional interstate channels were blocked due to the deterioration of relations with the West and sanctions. Such businessmen include, among others, Konstantin Malofeev, Vladimir Yakunin, and Yevgeny Prigozhin. The first two implement Russian conservatism projects (by sponsoring international meetings of ultra-right parties (Laruelle, 2018) and international conservative forums, such as the aforementioned Dialogue of Civilizations), while Prigozhin is more involved in pragmatic political projects (“troll factory,” arrangements for the work of foreign observers at elections in African countries (Shekhovtsov, 2020); etc.). These projects are part of the updated soft power strategy, which is significantly different from its previous version during the first two periods, and from Nye’s authentic concept.

So, the distinctive features of the third stage in the development of Russian soft power are not only its tightening and governmentalization, which largely reflect the overall tightening of Russia’s foreign policy as a whole. Russian international media have got actively involved in the global information war, in which no holds barred, while work with compatriots has become radically politicized, leading to even greater fragmentation and polarization of the Russian emigrant community.

A fundamentally new feature of the third period is the new ideological content, which is, in fact, diametrically opposite to the narrative the Russian government conveyed through soft power in the 2000s. Conservatism chosen for this purpose does have some potential in the modern global struggle of ideas, but at the same time this is a controversial ideological basis, both from the point of view of modern Russian society itself and from the point of view of its substance.

* * *

In almost twenty years of its existence, Russia’s soft power strategy has gone a long way from its rise to tightening. Today, it remains in Russia’s foreign policy arsenal, but it evokes a controversial reaction from the Russian leadership and is referred to abroad solely in the context of information and hybrid wars. How effective is the Kremlin’s strategy? The goal of voicing the “Russian position on key issues of world politics” and opposing anti-Russian propaganda has rather been achieved, albeit with reservations: appropriate media tools have been created but their reputation losses damage the perception of Russia and the Russian position by foreign audiences.

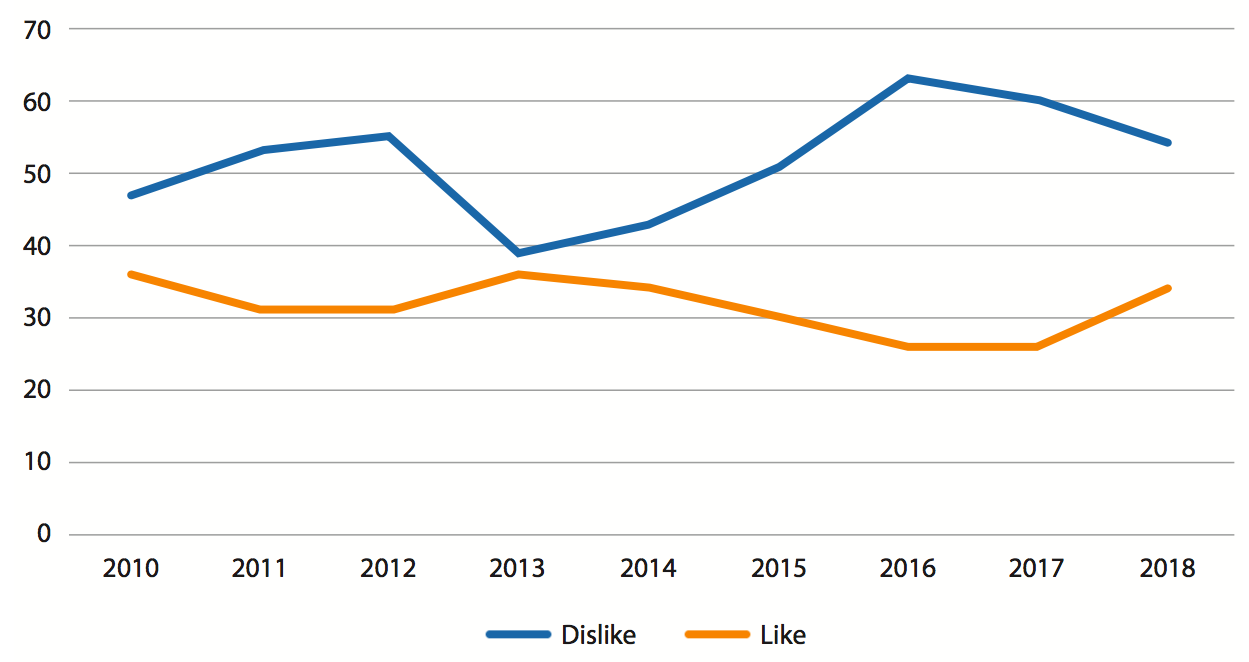

Figure 1. Assessment of Russia’s Role in International Relations

Source: Compiled by the author on the basis of Pew Research Center data.

As for control over the post-Soviet space and the protection of Russia’s own regime from external influence, the results are rather debatable since every year more and more CIS countries prefer exclusive cooperation with Russia to a multi-vector policy, and in Russia itself the consensus around stability is gradually waning amid the growing public demand for change (Znak.com, 2019).

As far as the improvement of Russia’s international image is concerned, the situation is not so clear. In the international soft power ranking, Russia is at the bottom of the list: 28th place out of 40 in 2012, failed to get into the ranking in 2015, 27th place out of 30 in 2016, 26th place out of 30 in 2017, 28th place out of 30 in 2018, and 30th place out of 30 in 2019 (The Soft Power 30, 2019). Public opinion polls show that the attitude towards Russia in the world is rather negative: Russia is viewed as an aggressive and unpredictable country.

So, it appears that one of the main goals the Russian leadership set for the soft power strategy, namely, improving the country’s image and conveying unbiased information about its current successes, has not been achieved. We can assume that the reason is not that Russia made a U-turn in 2012-2014 and chose conservatism as its foreign policy narrative. In fact, for a number of reasons conservative ideology is now in demand in Europe and the United States, which remain Russia’s “best frenemies.”

The most important secret of soft power, which Vadim Kononenko wrote about in 2006, seems to be eluding the Russian leadership. Regardless of ideological orientation—conditionally liberal or conservative—Russia should build an attractive socio-economic model, which will ensure cultural attractiveness of the country and society, scientific and intellectual potential, and, naturally, lifestyle (Kortunov, 2013). So the main problem remains the same: not how to build an attractive image of Russia, but how to make Russia itself attractive (Kononenko, 2006).

Ageeva, V., 2016. Rol’ instrumentov “myagkoi sily” vo vneshnei politike Rossiiskoi Federatsii v kontekste globalizatsii [The Role of Soft Power Instruments in the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation in the Context of Globalization]. PhD Thesis. St.-Petersburg State University.

Batanova, O., 2009. Russky mir i problemy ego formirovaniya [The Russian World and the Problems of Its Genesis]. PhD thesis synopsis, Russian Academy of Public Service, Moscow.

Borisova, E., 2015. Myagkaya sila—sovremenny instrumentariy vlasti (predislovie sostavitelya) [Soft Power as a Modern Instrument of Power (Editor’s Foreword)]. In: Borisova, E. (ed.). Myagkaya sila. Magkaya vlast’. Mezhdistsdiplinarny analiz [Soft Power. Soft Authority. An Interdisciplinary Analysis]. Moscow: FLINTA, Nauka.

CAPS & IRSEM, 2018. Les manipulations de l’information. Un défi pour nos démocraties Un rapport du Centre d’analyse, de prévision et de stratégie. CAPS, ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères et de l’Institut de recherche stratégique de l’École militaire [online]. Available at: <www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/les_manipulations_de_l_information_2__cle04b2b6.pdf> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Chakelyan, A., 2015. “I Hate Censorship”. Larry King on His Journey from Prime Time TV to Russia Today. NewStatesman, 30 November [online]. Available at: <www.newstatesman.com/politics/media/2015/11/i-hate-censorship-larry-king-his-journey-prime-time-tv-russia-today> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Chitty, N., Ji, L., Rawnsley, G., and Hayden, C., 2017. The Routledge Handbook of Soft Power. Routledge.

Dudenkova, I., 2017. Rossiyanki vybirayut rastit’ detei bez muzha [Russian Women Choose Single Parenting]. Rosbalt, 10 February [online]. Available at: <www.rosbalt.ru/moscow/2017/02/10/1591028.html> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Engel, V., 2019. Chto ob’edinyaet rossiyan [What Unites Russians]. Kommersant, 23 December [online]. Available at: <www.kommersant.ru/doc/4205791> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Gabuev, A. and Tarasenko, I., 2012. Piarova pobeda [A PR-Hype Victory], Kommersant-Vlast’, 9 April [online]. Available at: <www.kommersant.ru/doc/1907006> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Grigoryeva, E., 2007. Rossiya profinansiruet evropeiskuyu demokratiyu [Russia to Finance European Democracy]. Izvestia, 29 October [online]. Available at: <archive.is/20120802103251/www.izvestia.ru/politic/article3109784/#selection-811.714-811.890> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Faith Index, 2017. Indeks very: skol’ko na samom dele v Rossii pravoslavnyh [Faith Index: How Many Russian Orthodox Believers There Are]. Ria Novosti, 28 August [online]. Available at: <ria.ru/20170823/1500891796.html> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

KAPO, 2018. Estonian Internal Security Service Annual Review [online]. Available at: <kapo.ee/en/content/annual-reviews.html> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Karaganov, S., 2019. A Predictable Future? Russia in Global Affairs, 17(2) (April-June) [online]. Available at: < https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/a-predictable-future/> [Accessed 30 November 2020]. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2019-17-2-60-74

Kononenko, V., 2006. Sozdat’ obraz Rossii? [Creating the Image of Russia?]. Rossiya v global’noi politike, 4(2) [online]. Available at: <globalaffairs.ru/articles/sozdat-obraz-rossii/> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Konygina, N., 2007. Vremya sobirat’ tserkvi [Time to Gather Churches]. Rossiiskaya gazeta, 18 May [online]. Available at: <rg.ru/2007/05/18/akt.html> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Kortunov, A., 2013. Myagkaya sila Rossii? Gde i kak ona proyavlyaetsa? [Russia’s Soft Power? Where and How Does It Manifest Itself?]. “Kultura” TV-Channel, 20 May [online]. Available at: <russiancouncil.ru/news/myagkaya-sila-rossii-gde-i-kak-ona-proyavlyaetsya-diskussiya/?sphrase_id=1820142> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Kosachev, K., 2012. The Specifics of Russian Soft Power. Russia in Global Affairs, 10(3) (July–September) [online]. Available at: <eng.globalaffairs.ru/issues/2012/3/> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Kosachev, K., 2013. Myagkaya sila i zhostkaya sila: ne summa, no proizvedenie [Soft Power and Hard Power: Not a Sum, But a Product]. Indeks bezopasnosti, 107(4) [online]. Available at: <www.pircenter.org/media/content/files/12/13880428660.pdf> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Kramer, R., 2017. Russian TV Crew Tries to Bribe Swedish Youngsters to Riot on Camera. Foreign Policy, 17 March [online]. Available at: <foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/07/russian-tv-crew-tries-to-bribe-swedish-youngsters-to-riot-on-camera-stockholm-rinkeby-russia-disinformation-media-immigration-migration-sweden/> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Laruelle, M., 2018. Le “soft power” russe en France: La para-diplomatie culturelle et d’affaires. Carnegie Council, 8 January [online]. Available at: <www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/articles_papers_reports/russian-soft-power-in-france/_res/id=Attachments/index=0/Le%20soft%20power%20Russe%20en%20France_2.pdf> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Limonier, K. and Audinet, M., 2017. La stratégie d’influence informationnelle et numérique de la Russie en Europe. Hérodote, 164(1), pp.123-144.

Lenta.ru, 2015. My vytolknuli Ukrainu iz Russkogo mira [We Have Ousted Ukraine from the Russian World]. Lenta.ru, 17 May [online]. Available at: <lenta.ru/articles/2015/03/17/crimea/> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Loukianov., F., 2013. Les paradoxes du soft power russe. Revue internationale et stratégique, 4(92), pp.147-156.

Lukyanov F., 2016. Ne samaya obayatel’naya i privlekatel’naya [Not the ‘Princess Charming’]. Gazeta.ru, 6 June [online]. Available at: <www.gazeta.ru/comments/column/lukyanov/8310815.shtml> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Makur, J., 2014. Amid the Triumphs, an Argument for Tolerance. The New York Times, 23 February [online]. Available at: <www.nytimes.com/2014/02/24/sports/olympics/olympic-closing-ceremony-proves-russia-a-worthy-host.html?_r=0> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

MFA, 2013. Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 12 February [online]. Available at: <www.mid.ru/web/guest/foreign_policy/official_documents/-/asset_publisher/CptICkB6BZ29/content/id/122186?p_p_id=101_INSTANCE_CptICkB6BZ29&_101_INSTANCE_CptICkB6BZ29_languageId=en_GB> [Accessed 14 September 2020].

MFA, 2016. Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation [online]. Available at: <www.mid.ru/foreign_policy/official_documents/-/asset_publisher/CptICkB6BZ29/content/id/2542248?p_p_id=101_INSTANCE_CptICkB6BZ29&_101_INSTANCE_CptICkB6BZ29_languageId=en_GB> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Nikonov, V., 2007. Stenographichesky otchet o vstreche s chlenami Soveta Obstchestvennoi palaty Rossii [Transcript of the Meeting with the Members of the Council of the Russian Public Council]. Kremlin.ru, 16 May [online]. Available at: <kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/24263> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Nye, J. (Jr.), 2001. The Future of Power. New York: Public Affairs.

Nye, J. (Jr.), 2013. What China and Russia Don’t Get About Soft Power. Foreign Policy, 29 April [online]. Available at: <foreignpolicy.com/2013/04/29/what-china-and-russia-dont-get-about-soft-power/> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Nye, J. Jr., 2018. How Sharp Power Threatens Soft Power. Foreign Affairs, 24 January [online]. Available at: <www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-01-24/how-sharp-power-threatens-soft-power> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Petro, N., 2015. Russia’s Orthodox Soft Power. Carnegie Council, 23 March [online]. Available at: <www.carnegiecouncil.org/en_US/publications/articles_papers_reports/727/_view/lang=en_US> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Poloskova, T., 2020. Primakov—posledniy shans Rossotrudnichestva i “myagkoi sily” Rossii [Primakov as the Last Chance of Rossotrudnichestvo and Russia’s “Soft Power”]. Realist, 15 July [online]. Available at: <realtribune.ru/news/news/4653> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Porubova, K. and Anufrieva, K., 2020. “Mir pogruzilsia v gibridnuyu voinu” [“The World Is Bogged Down in the Hybrid War.” Interview with Margarita Simonyan]. Radio “Komsomolskaya Pravda”, 30 July [online]. Available at: <www.kp.ru/online/news/3961362/> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Putin, V., 2013a. Meeting of the Federal Security Service Board. Kremlin.ru, 14 February [online]. Available at: <en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/17516> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Putin, V., 2013b. Security Council Meeting. Kremlin.ru, 5 July [online]. Available at: <en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/18529> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Putin, V., 2013c. Torzhestvenny vecher, posvyashchyonny Dnyu rabotnika organov bezopasnosti [Gala Evening Party to Mark Security Agency Worker’s Day]. Kremlin.ru, 20 December [online]. Available at: <kremlin.ru/events/president/news/19872> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Putin, V., 2013d. Address to the Valdai International Discussion Club, Kremlin.ru, 19 September [online]. Available at: <en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/19243> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Putin, V., 2013e. Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly. Kremlin.ru, 12 December [online]. Available at: <en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/19825> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Putin, V., 2014. Address to of the Valdai International Discussion Club. Kremlin.ru, 24 October [online]. Available at: <en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/46860> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

RG, 2014. Parizh, Sevastopol’sky bul’var [Paris, Sevastopol Boulevard]. Rossiiskaya gazeta, 25 December [online]. Available at: <rg.ru/2014/12/25/pismo.html> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Robinson, P., 2020. Russia’s Emergence as an International Conservative Power. Russia in Global Affairs, 18(1) (January-March), pp.10-37. Available at: <eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/russias-conservative-power/> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Rutenberg, J., 2017. RT, Sputnik and Russia’s New Theory of War. The New York Times, 13 September [online]. Available at: <www.nytimes.com/2017/09/13/magazine/rt-sputnik-and-russias-new-theory-of-war.html> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Senyavsky, A.S. and Senyavskaya, E.S, 2009. Vtoraya mirovaya voina i istoricheskaya pamjat’: obraz proshlogo v kontekste sovremennoi geopolitiki [World War II and Historical Memory: The Image of the Past in the Context of Modern Geopolitics]. Vestnik MGIMO. Special Issue, pp.299-310.

Shekhovtsov, A., 2020. Fake Election Observation as Russia’s Tool of Election Interference: The Case of Africa. EPDE Publication, 10 April [online]. Available at: <www.epde.org/en/news/details/fake-election-observation-as-russias-tool-of-election-interference-the-case-of-afric-2599.html> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

SVOP, 2016. Strategiya dlya Rossii. Rossiiskaya vneshnyaya politika: konets 2010-h – nachalo 2020-h [Strategy for Russia. Russia’s Foreign Policy: Late 2010s – Early 2020s]. Theses of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy Working Group [online]. Available at: <svop.ru/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/тезисы_23мая_sm.pdf> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

The Insider, 2017. Kak vryot telekanal Russia Today [How Russia Today Lies]. The Insider, 31 May [online]. Available at: <theins.ru/antifake/58435> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

The Soft Power 30 Report, 2019. The Soft Power 30. A Global Ranking of Soft Power. Portland. Available at: <softpower30.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/The-Soft-Power-30-Report-2019-1.pdf> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Tsygankov, A., 2013. Vsesil’no ibo verno? [Omnipotent Because True?] Rossiya v global’noi politike, 11(November/December) [online]. Available at: <globalaffairs.ru/articles/vsesilno-ibo-verno/> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Van Herpen, M., 2016. Putin’s Propaganda Machine. Soft Power and Russian Foreign Policy. Rowman & Littlefield.

Van Herpen, М., 2019. The Political Role of the Russian Orthodox Church. The National Interest, 19 November [online]. Available at: <nationalinterest.org/feature/political-role-russian-orthodox-church-97647> [Accessed 30.11.2020].

von Gan, A., 2014. Al’ternativnoye pis’mo potomkov belyh emigrantov [Alternative Letter from the Descendants of White Emigrants]. Beloye Delo, 28 December [online]. Available at: <beloedelo.com/actual/actual/?327> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Yablokov, I., 2015. Conspiracy Theories as a Russian Public Diplomacy Tool: The Case of Russia Today (RT). Politics, 35(3), pp.301-315.

Yakovlev, V., 2017. Upotreblyat’ termin ‘Global Russians’ segodnya v printsype nepristoino [It’s Essentially Indecent Nowadays to Use the Term ‘Global Russians’]. Zima Magazine, 3 July [online]. Available at: <zimamagazine.com/2017/07/vladimir-yakovlev-upotreblyat-termin-global-russians-segodnya-v-printsipe-nepristojno/> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Yeryomina, N., 2017. Rossiyane brosayut sem’i [Russians Leave Families], Gazeta.ru, 13 August [online]. Available at: <www.gazeta.ru/business/2017/08/10/10826804.shtml> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Zavadski, K., 2015. Putin’s Propaganda TV Lies About Its Popularity. The Daily Beast, 17 September [online]. Available at: <www.thedailybeast.com/putins-propaganda-tv-lies-about-its-popularity> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Znak.com, 2019. Proiskhodit revolyutsiya v massovom soznanii rossiyan [There Is a Revolution in Russians’ Mass Consciousness]. Znak.com, 20 May [online]. Available at: <www.znak.com/2019-05-20/proishodit_revolyuciya_v_massovom_soznanii_rossiyan_intervyu_s_sociologom> [Accessed 30 November 2020].

Zygar, M., 2016. All the Kremlin’s Men: Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin. PublicAffairs.