The study of the crises in 2020 raises the question: What impact will they have on the structure of international relations? Clearly, the year 2020 will be remembered as a year of global challenges.

The present paper argues that the COVID-19 pandemic and the systemic response to it have intensified the ongoing shifts in the global distribution of power. The international response to the pandemic has shown a lack of multinational cooperation, relative ineffectiveness of multilateral organizations, such as the United Nations and the World Health Organization, and the tendency of states tackling the pandemic to pursue their own interests. The erosion of multilateralism and self-help behavioral practices are indicative of the extent to which the international structure has shifted towards a more self-centered one. Thus, it is highly likely that the outcome of the COVID-19 crisis will be China’s further rise, Russia’s renewed great power status and the U.S.’s relative decline, together with increased influence of alternative meaningful centers of powers.

At the same time, one cannot claim that the COVID-19 crisis is the primary variable behind the structural shifts, and the real impact of the global pandemic is yet to be revealed. The article’s main argument is that the structural changes began before the 2020 crises, while the recent emergencies accelerate the ongoing redistribution of power rather than create new dynamics in the international structure.

Political experts writing about the COVID-19 pandemic’s structural impact largely agree that it can boost the changes that have already begun. Campbell and Doshi claim that the U.S. is losing to China as this Asian great power is expected to lead again in the global economic growth. Russian scholar Maxim Bratersky (2020) argues that the pandemic’s potential is a substituent of the hegemonic war. Joseph Nye, on the contrary, in his latest report (2020) denies the thesis that China can take over the global order as it lacks soft power potential. Mike Green (2020) stresses that it is the crisis of the U.S. leadership rather than China’s competence that is essential for taking over global leadership; he believes that the U.S. can consolidate its power and continue leading the world. Another scholar denying the possible shift in the global order, Judah Grunstein (2020), asserts that the pandemic can strengthen competition among strong powers—China, the U.S., and the EU—rather than alter the international order. Oskar Krejčí also thinks that the structure of international relations will remain unchanged as there is no infrastructure for altering the current order (Krejčí, 2020). All these scholars proceed from the assumed need for leadership in the international structure or imminent establishment of a new order. Meanwhile, the belief that the relative decline in the U.S. global leadership was caused by Trump’s incompetence is again wrong. Despite the evident lack of coherent and competent foreign policy of the Trump administration, the ongoing changes are structural, and Joe Biden, too, will face the harsh reality of the relative decline of U.S. power and influence.

Another description of current dynamics comes from Richard Haass who asserts that the pandemic is likely to accelerate changes in the world order (Haass, 2020). Haass supports a nonpolar configuration over the multipolar one (Haass, 2008). Fyodor Lukyanov and scholars gathered around the Valdai Club, a Russian think tank, share a similar view, claiming that the pandemic is boosting the changes that started in the previous period, while the structural dynamics will continue (Lukyanov, et.al., 2020). In this article the discussion centers around the pandemic’s potential for accelerating the structural changes, with the significantly weakened West lacking the capacity to sustain the liberal order globally. The paper raises the question of whether the bottom-up and top-down challenge to the traditional international system and increased power diffusion and disorder attribute to the prevailing nonpolarity, or the revival of great power rivalries signals a shift towards a more common bi-, tri- or multipolar structure of the international system. The results of the analysis demonstrate that the international structure contains features of both nonpolar and polar configurations.

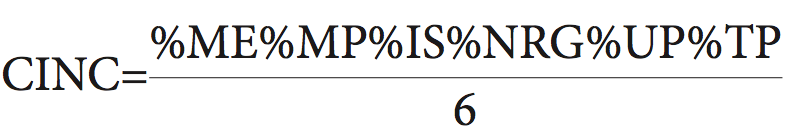

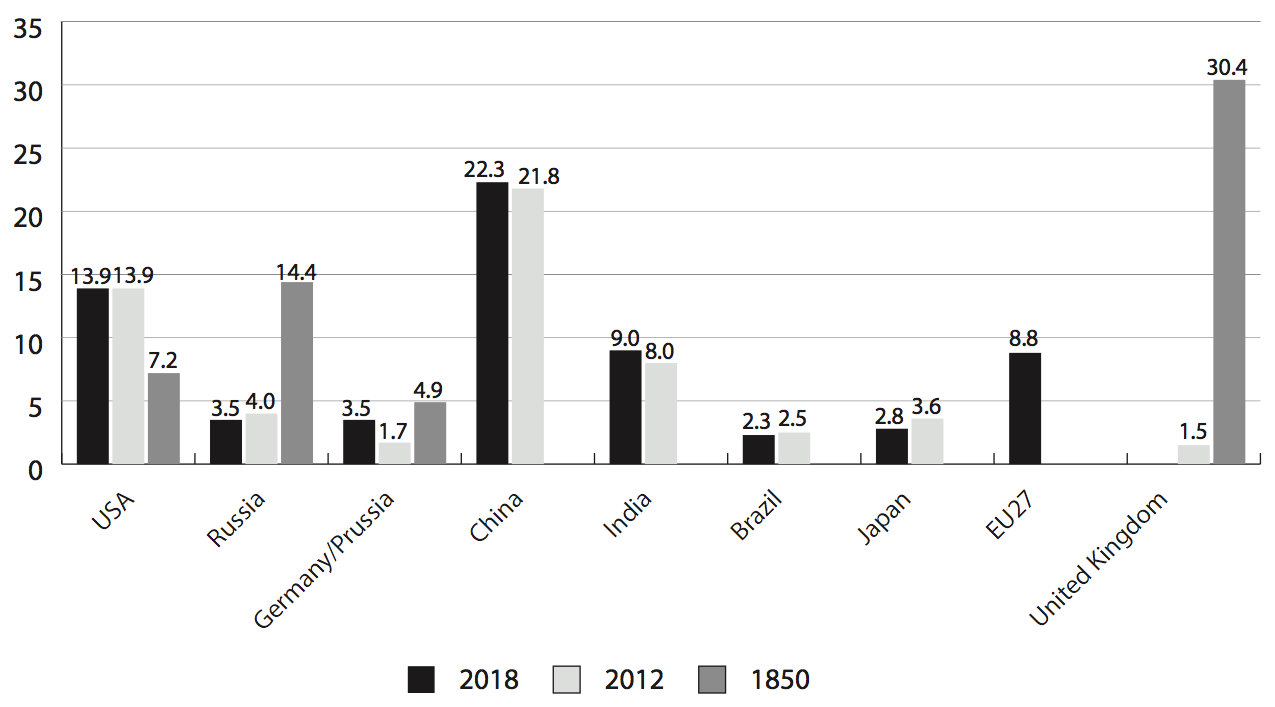

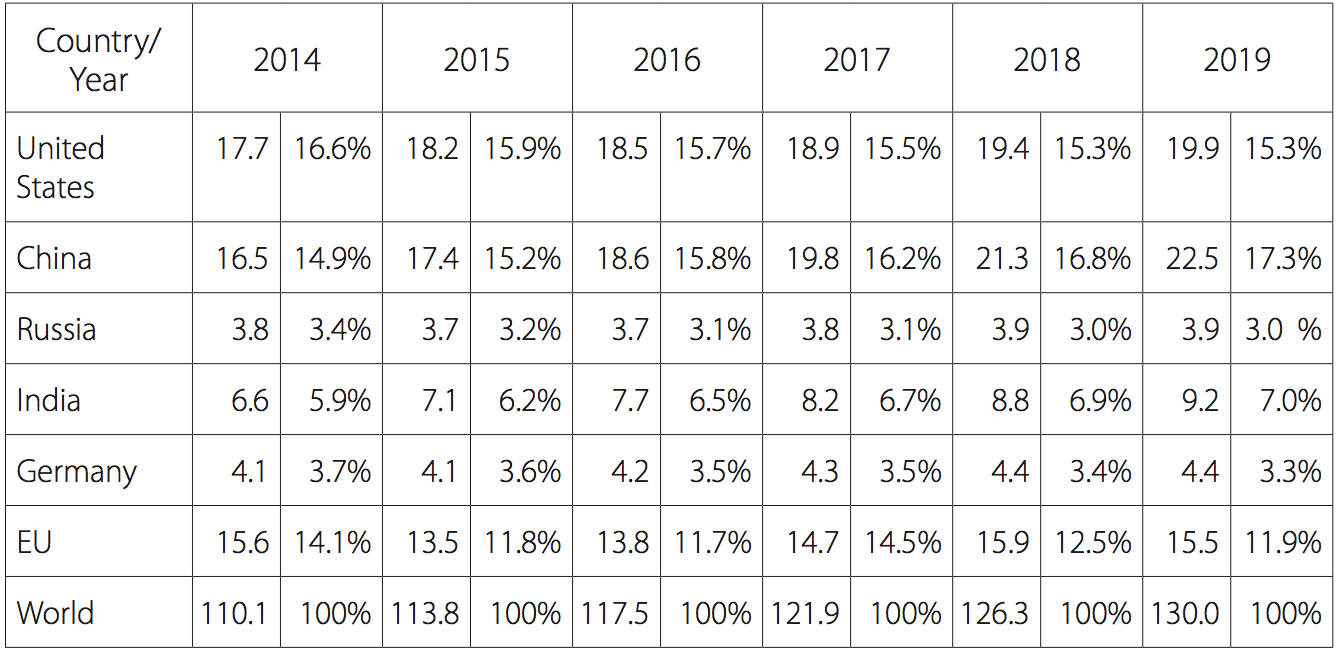

The first section of this paper gives an overview of the most frequent arguments about the contemporary structural shifts; the second section describes the results of a unit-level analysis of the U.S., China, Germany, Russia, and the EU cases; and the final section offers an assessment of the external factors that influenced international affairs in 2020 and outlines conditions under which the international structure can shift towards a nonpolar, bipolar, or multipolar configuration. The combination of the structure-level and unit-level analyses provides an insight into the latest developments in great power politics. The main argument is tested by a comparative analysis of available theoretical assumptions and data on the great powers’ capabilities. The assessment of the pre-crisis position of the selected actors is based on the Correlates of War model, which contains data on the actors’ GDP over the past five years and tracks their share in the global GDP (Singer, Bremer and Stuckey, 1972). Following these changes in power, the distribution illustrates the pre-crisis structural dynamics and shows the actors’ current power capabilities and likely structural changes in the future. Simultaneously, the Composite Index of National Capabilities (CINC) data illustrates the current material balance of power. Table 1 compares CINC data for 1850 as the year characteristic of the pre-Crimean War balance of power that is viewed as the peak of the 19th-century multipolarity, for 2012 as a year prior to the peak in Russia-West tensions and U.S. GDP remaining the world’s largest, and, finally, for 2018 as the most recent CINC to evaluate the current balance of material capabilities. Also, the data for 1850, 2012 and 2018 is used to compare different periods and show that the multipolar power configuration does not necessarily require a group of equal or near-equal great powers. We used the CINC formula as follows:

% M.E. — military expenditure as a percentage of world total;

% M.P. — military personnel as a percentage of world total;

% I.S. — 1816-1895: iron production as a percentage of world total; 1896: steel production as a percentage of world total;

%NRG — energy consumption as a percentage of world total;

%UP — urban population as a percentage of world total;

% T.P. — total population as a percentage of world total (Singer, Bremer and Stuckey, 1972).

Grasping the Post-Unipolar Structure

The thesis about the current tendency towards multipolarity can be found in recent works of Schweller and Pu (2011), Posen (2014), Monteiro (2011), Kortunov (2018) and earlier works of Mearsheimer (2001) and Waltz (1993). The official documents of the EU, China, and Russia also contain statements about the ongoing formation of a multipolar international structure and point to the National Intelligence Council regular prognosis, Global Trends 2025 and its latest version Global Trends 2030, which includes the diffusion of power into “megatrends” and claims that “power will shift to networks and coalitions in a multipolar world” (National Intelligence Council, 2012, p. 2). In contrast, international relations experts offer alternative assumptions about the formation of uni-, multi-, bi- or nonpolar configurations.

Nonpolarity as the most challenging of these configurations implies the diffusion of power into many centers of “meaningful power” (Kopalyan, 2017; Haass, 2008, 2018) and stresses the importance of non-state actors, such as transnational corporations, international institutions, and terrorist groups (Haass, 2008).

The nonpolarity thesis describes the qualitative and quantitative changes to the system of international relations and, as illustrated by Kopalyan, claims that historically nonpolarity occurred rather frequently, although not globally, since the 16th century.

Nonetheless, the nonpolarity concept is a rarity, it lacks precise structural characteristics, the description of the actors’ usual behavioral patterns, the conditions that foster it and those which foster shifts from it. Remarkably, Kopalyan (2017) and Haass (2008, 2018) provide different understandings of nonpolarity. Richard Haass offers the most detailed description as he focuses on contemporary international affairs and their qualitative changes. Kopalyan, in contrast, looks at unipolarity as a structural variable fostering transition to nonpolarity and refrains from a detailed definition of the actors’ behavior. He studies the frequency of nonpolarity occurrences and the probability of nonpolarity formation directly after the unipolar configuration. Also, Kopalyan provides an impressive database showing the structural changes that occurred in world history from 2000 B.C. until the 2000 A.D. Like Kopalyan, Wilkinson (1987, 1999) includes nonpolarity in his taxonomy as one of possible structures, but he refrains from conceptualizing a systemic framework (2004). These two scholars agree in that the nonpolar configuration is likely to occur as a result of power transition from unipolarity with extreme accumulation of power in the hegemon’s hands. So it appears that the more intense concentration of power is, the greater diffusion of power occurs at the end of the structure’s lifetime.

Kopalyan states that nonpolarity differs from multipolarity in the number of subsystem hegemons exceeding seven, and others add that nonpolarity is characterized by disorder, entropy and randomness as there are no systemic constraints on the actors’ behavior. A watchful observer might add that nonpolarity occurs when the unipole is no longer capable of maintaining the order and the system lacks a challenger or a group of them. For example, Russia’s and China’s current interests in dismantling the U.S.-led liberal order are based on balancing the hegemon, but not overtaking its position.

Haass adds increased importance of middle powers to his definition but refrains from determining when an actor becomes and ceases to be what he calls the “center of meaningful power.” Behavioral patterns of great powers are another problem in defining nonpolarity. They mostly escape the attention of scholars, except for Kopalyan who maintains that nonpolarity is free of balancing behavior. He defines nonpolarity as the “diffusion of power and dispersion of resources against or with numerically high actors, where balancing is untenable” (Kopalyan, 2017, p. 3). Simultaneously, the need for counterbalancing decreases with a greater diffusion of power due to the smaller chances for actors to become hegemons, i.e. challengers of the status quo.

In contrast, Haass encourages the U.S. to employ the strategy of containment and deterrence vis-à-vis Russia and China; in other words, he favors balancing behavioral patterns that are common in bi-, tri- and multipolar structures. Both Russia and China seek to counterbalance Western interests in Africa, Latin America, East Asia, and the Middle East, while the U.S. and the EU seek to contain Russia and China. Therefore, all great powers engage in the balancing behavior and form balancing blocs.

Here another question arises: What does meaningful power really mean? The recent cases of the U.S. pharma companies Moderna and Pfizer favoring the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines in the West, and global reliance on spaceports that are controlled by particular actors have proved that possession of hi-tech or other research programs makes some states more privileged than others regardless of their place in the power distribution system. Tatiana Shakleina distinguishes several essential assets of great powers: territory, natural resources, demography, military potential, economy, hi-tech development, science and research, education, culture, and tradition to think and act globally. At the same time, she identifies the U.S., China, Russia, India, and Brazil as major powers of today, although some of them do not meet all of the above criteria (Shakleina, 2011, p. 29).

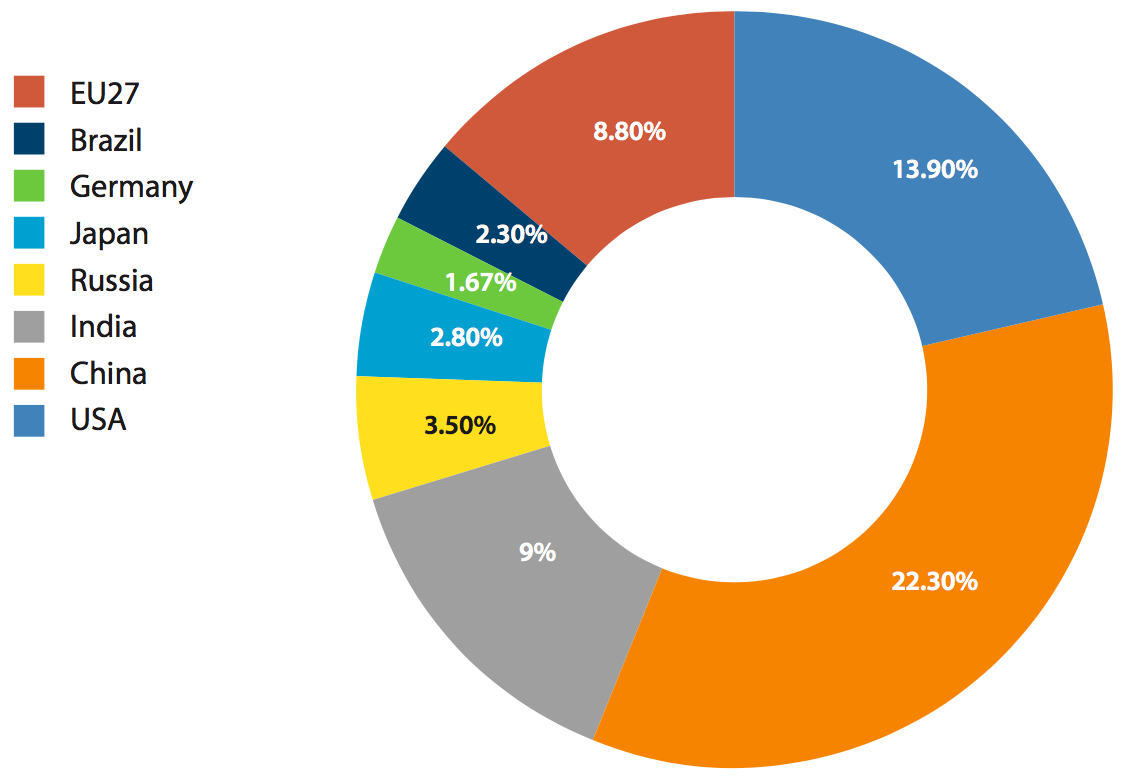

As Fig. 1 shows, power distribution at the peak of the Concert of Europe was as uneven as it is in the contemporary international structure. The multipolar structure is not usually free of disorder either. For instance, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the U.S. developed an opportunism-driven approach that initially lacked the ambition to alter the world order. Graphic examples are Germany’s pre-Weltpolitik foreign policy of Realpolitik, U.S. isolationism, and the Monroe Doctrine. Thus, power disproportionalities and opportunistic aspirations among the most capable actors are a feature of both non- and multipolar structures. However, vertical power distribution still indicates that some actors can develop anti-COVID vaccines, or launch satellites vital to contemporary society, while others can only rely on them. Richard Haass admits that “China, the European Union, India, Japan, Russia, and the United States account for 75 percent of global GDP and 80 percent of global defense spending” (Haass, 2008).

The proponents of nonpolarity correctly attribute quantitative changes in the system that reflect power diffusion and amend the great power politics. Actors like Turkey, Iran, North Korea or Venezuela continue to defy materially preponderant great powers’ interests. It is questionable whether these centers of meaningful power will be able to pursue increasingly independent agendas, or the stronger actors would want or be able to drag them into their orbits. International institutions providing bandwagoning for profit, or freeriding might be an answer here. Because as liberal institutionalists assume, institutions and other non-state actors are here to stay despite the increasing disorder due to their practical nature (Nye, 2020; Keohane, 2020; Ikenberry, 2018).

The 21st-century nonpolar configuration is in many respects novel to the global system. Yet both Kopalyan and Haass admit that nonpolarity as a concept requires further research. This concept lacks a unified definition of nonpolarity tested by case studies and the study of global nonpolarity that would identify its contemporary characteristics. Also, we lack research on the behavioral patterns of actors in the nonpolar configuration where great powers engage in balancing behavior (contrary to what Kopalyan claims) while small states mostly freeride on the U.S.-led liberal order remnants and middle powers use the absence of great power blocs as an opportunity to gain as much power as possible. Hence it would be interesting to research what contributes to such diffusion. Is it the lack of power distribution infrastructure? Such as alliances, access to resources, technology, or institutions that would help maintain the order?

Furthermore, Kopalyan’s comprehensive database suggests that nonpolarity can be a phase in the power redistribution after the hegemonic order collapses as a result of excessive dominance of the unipole. Such redistribution can cause diffusion of power and chaos reminiscent of the decline of Pax Romana. Historical research of power transitions also shows that the lifespan of power configurations decreases owing to the technological advances that increase the speed of movement and information. In this context, it would be interesting to see whether this redistribution will result in a bi-, tri- or multipolar structure, or we will witness global nonpolarity as a novel structural configuration of the global system.

Figure 1. Composite Index of National Capabilities

To sum it up, one can currently observe features of both non- and multipolar configurations with less than seven major powers—the U.S., China, Russia, India, Brazil, and the EU—acting on the international stage. These major powers are disproportionally capable but still preponderant over other actors in the structure. They engage in balancing behavior but lack the ambition, or capabilities, to alter the existing status quo. This finding might be novel to the nonpolarity/multipolarity debate as, on the one hand, balancing behavior is typical of polar configurations and, on the other hand, the disorder and randomness coupled with the lack of an alternative structure is specific of nonpolarity. Such disorder fosters opportunism as there are no structural constraints on relatively weak but still capable actors.

Unit-Level Analysis

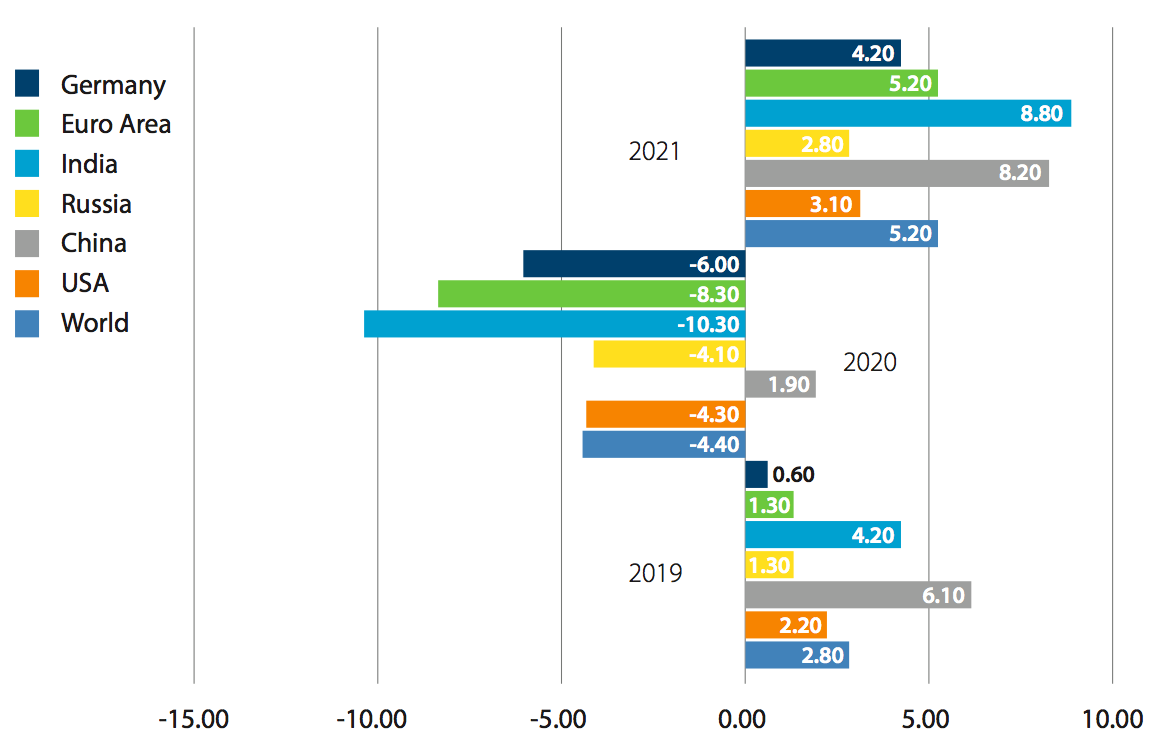

The COVID-19 pandemic has proven to be the most destabilizing element in international relations since World War II. The pandemic has shaken the economies of states and closed the borders, which has resulted in a historically unprecedented slowdown of the global economy. Across the globe, the political elites and strategic communities had failed to prepare for a future pandemic, even though pandemic scenarios were among the most frequently simulated ones in global crisis forecasting. Notwithstanding the substantial help designed by the states to boost their economies and the first signs of recovery, the latest data released by the IMF (see Fig. 2) shows that the world economy has encountered a historical crisis. According to the October 2020 IMF estimate, the global growth in 2020 is projected at 4.4%, which is 1.5% below the April World Economic Outlook forecast and is 4.8% lower than during the 2009 financial crisis (Gopinath, 2020). The West and Russia seem to be struck the most as their average contraction is estimated at 6.1%, while developing and emerging markets are expected to shrink by 3% on average.

Figure 2. IMF World Economic Growth Projections (as of October 2020)

Source: International Monetary Fund.

The United States

Over the last three decades the U.S. has enjoyed the primacy and still remains the system’s most potent power. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, U.S. GDP stands at $20 trillion and its military budget surpasses the other nine out of the world’s ten biggest military spenders. Furthermore, the U.S. has managed to establish an impressive network of alliances across the globe. NATO remains the mightiest military alliance in humankind’s modern history, and its presence prevented the rise of the European continent in the balance of power. At the same time, the Asian partnership in the alliance oversees the maintenance of the status quo in the Pacific. In the Middle East, Israel and oil-rich Gulf states, such as Saudi Arabia, also stand behind the back of the most influential actor in the system. However, the U.S. has encountered a series of setbacks and a decline of its influence over the past five years. Firstly, public unrests triggered by the political and social divide have become increasingly violent and frequent in the past few years. This was evident already in 2014, when the Pew Research found out that approximately 40% of voters of both parties in the U.S. saw each other increasingly unfavorable, as compared to 1994. At the same time, 73% of all U.S. voters responded that they could not agree on the other party voters’ basic facts in 2020 (Pew Research, 2014, 2020). Thus, the social rift is certainly one of the most pressing challenges for Joe Biden’s administration. Secondly, the U.S. economic power faced a slight decline in previous years as it lost 1.3% in the global share, mostly due to China’s and India’s ascend (see Table 1). The expected negative growth is likely to foster these shifts as China grew even at the cost of substantial losses (4.1%).

Table 1. World GDP and Major Actors’ GDP, constant USD, trillion; Share of the Major Actors in World GDP, %

As regional powers, Russia and China sought to pursue their own interests. The U.S. has proven incapable of simultaneously containing the two peer competitors on the global scale. China outnumbered the U.S. economically in the previous decade. To contain rising China, the Trump administration threatened its NATO allies to abandon its commitments if they did not contribute more and keep sustaining Obama’s Pivot to Asia incentive. However, Trump’s foreign policy course, if there was any, was conducted through unilateral actions at the expense of multilateralism, which has led to decreased cooperation in the international structure.

China

China is widely perceived as the challenger to the U.S. hegemony as it has turned into the largest economy with an unprecedented growth, which was masterly illustrated by Graham Allison in The Thucydides Trap. By adopting the so-called “alter-globalization” approach, for which a state’s internal structure does not matter, and using the win-win tactics China has solidified its sphere of influence in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and Africa. The win-win approach and economic benefits are the core principle of China’s soft power that attracts people and states across the globe, mostly for economic reasons (for example, more people tend to learn Chinese nowadays because of the newly opened business opportunities).

China’s soft power initiative, as David Shambaugh maintains, is well funded. By 2025 China plans to allocate $1.25 trillion worldwide, while the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank will receive $50 billion; the New Development Bank, $41 billion; the Silk Road Economic Belt, $40 billion; and the Maritime Silk Road, $25 billion. By contrast, the Marshall Plan cost the equivalent of $103 billion in today’s dollars (Shambaugh, 2015). At the same time, the image of China has suffered significant damage as the country tried to camouflage the virus outbreak and persecuted whistle-blowers, while China’s image in the West is at an all-time low: 60-80% of populations maintain negative views on China, as the recent Pew Research polls illustrate (Pewresearch, 2020).

On the other hand, developing markets and Third World countries are mostly Chinese expansion areas today. Therefore, it is hard to estimate whether the developing African, Asian or Latin American countries will snub easy-to-receive, politically unbiased, but rather risky loans as a reaction for Chinese mismanagement of the virus outbreak.

According to our COW model, China is rising and gained roughly 3% of the GDP share among the selected great powers during the 2014-2019 period.

Meanwhile, China is struggling with several problems. Firstly, its military potential is far from that of the U.S., but already capable enough to alarm the whole region as “Pentagon planners and other regional militaries say they are wrestling with how to respond to something they haven’t seen since World War Two: a return to highly contested warfare at sea” (Lague and Lim, 2019). Secondly, despite the extensive efforts in tackling extreme poverty, China remains a middle-income country. And finally, the lack of reliable allies is making a Chinese structural takeover difficult. Even though the World Bank and IMF estimate that China will lead the global economic growth in 2021, its economic growth is expected to lose 5% and fall to 1%.

Russia

Mostly due to economic and demographic problems, Russia may be perceived as a declining power. According to our COW model, the country has lost 0.4 % in the World GDP share (from 3.4% to 3%), which indicates a slight economic decline. Nevertheless, one can hardly disagree with John Mearsheimer who labels Russia as a resurrected great power (Mearsheimer, 2018, 2019).

(The latter factor provides ammunition to proponents of persistent relevance of military power in the contemporary world (Monteiro, 2012; Layne, 2002).) The country managed to develop hypersonic weaponry and leads in hi-tech weaponry. It also successfully resisted the West’s pressure in the Maidan revolution aftermath, emerged as a power-broker in the Middle East, challenged the U.S. interests in Venezuela, and consistently seeks to restore its position in Africa (which goes back to the Soviet tradition of maintaining the sphere of influence in this region). However, the country is struggling with the consequences of the oil price war and the COVID-19 pandemic as the main threat to its diminishing population.

The World Bank and IMF estimates draw on the steep decline in Russia’s GPD growth down to -4.1%. Some point to Vladimir Putin’s waning popularity—from 85% to 64% in 2019, although in 2020 his popularity was between 65% and 69%. By comparison, Emmanuel Macron’s approval rating remains at 34%, while 60% of the population disapprove of his policies. At the same time, Angela Merkel’s all-time high approval rating was 68%, with 38% of the population disapproving of her Chancellorship, and Donald Trump’s approval rating remained at roughly 40% throughout his time in the Oval Office. Therefore, in comparison to European and American leaders, Putin enjoys a firm hold on power, and it is hard to imagine that the Russian establishment will collapse with the approval rates above 50% (Statista, 2020).

Nevertheless, contemporary Russia faces increasing internal pressure due to the need for economic and social reforms. Russia’s history illustrates that the domestic pressures caused more damage to the country than the external ones, even such as the 19th-century British containment, two World Wars, and the Cold War containment. If the Russian economy survives the COVID-19-related crises and overcomes the domestic problems, then, as the logic of realism tells us, it is likely to continue preying on the Western decline and situational disunity of the European Union. However, given the defensive nature of Russian foreign policy (Russian National Security Strategy, 2015) and insufficient power capabilities, the odds for Russia’s expansion to Europe, or at least its eastern regions, are relatively small.

The European Union and Germany

The EU’s relevance as an actor of international relations remains at the center of academic debate. When it comes to specific foreign-policy areas, such as the enlargement policy and international trade, the EU acts as a unitary actor.

Also, the vague decision-making process, as a result of overwhelming bureaucratization and lack of a unified approach, reflects an uncoordinated reaction to the ongoing rapid changes in the global international structure. In 2016, the EU issued its version of the Global Strategy that ambivalently relies on the liberal approach to the world that is marked by dispersed distribution of power (which the European Commission has admitted in several documents (European Commission, 2014, 2016)). There are many critics of the EU’s current foreign policy, although Andrew Moravcsik thinks the Union works slowly but effectively via a set of institutions and complicated integration processes, which make its policies “look dull and unattractive to pundits” (Moravcsik, 2020). Yet the increasingly competitive world rounds up the ranks of those who call for the Realist approach. As Sigmar Gabriel (2018) put it, “the EU is a vegetarian in a world full of carnivores, and vegetarians have a very tough time of it.”

Germany, as the largest economy and most influential actor within the EU, has encountered a slight decline over the last five years. Like the EU, Germany is struggling to find its place in the changing world. Germany’s major ally, the United States, threatened Europe with the abandonment of its alliance commitments and mutual relations were frozen due to the personal animosities between President Trump and Chancellor Merkel, or, to put it more accurately, the U.S. conservatives and the ruling European political elite. The situation, however, is likely to change with Joe Biden’s administration. Germany’s foreign policy strategy aims at boosting EU incentives of closer integration. These incentives might appear successful if the EU and Germany efficiently tackle the 2020 crises. Germany fares relatively well at the domestic level thanks to its modern high-capacity healthcare system and welfare-state measures. In other words, Germany confirms its leading role in the EU.

Overall, the EU represents one of the largest economies in the COW model, although over the last five years it has faced a 2.2% decline, caused mostly by Brexit and the economic growth slowdown. According to the IMF data, the EU economy is set to shrink by 7.6%, with the worst damage hitting the economies of Spain (12.8%), Italy (0.6%), and France (9.8%). However, the EU has recently released an impressive set of stimuli and started to coordinate the efforts of its member states to tackle the virus outbreak. Furthermore, the latest actions show that there is an understanding among the European leaders of the need to rely on survival logic in the global competition for power.

Systemic Variables

Amid the growing disorder, anarchy seems to be the underlying systemic characteristic of the states’ expansionist foreign policies when the structural conditions allow them to do so. Of course, there remain cooperation and mutual help in the behavior of great powers, but as Robert Jervis very recently stated, “the big states do a lot of good and bad things, they fight bloody wars, compete with other great powers, help their allies to maintain their sovereignty, but most importantly they care for their interests in the first place” (Jervis, 2020).

As Russia’s case demonstrates, the U.S.’s reluctance to spend more resources on its costly Middle East ventures came as an opportunity for Russia to skillfully exploit relevant actors’ interests to resolve the bloody war in Syria.

Subsequently, the Russian successes created demand for an alternative order where the state’s internal political structure would play a minor role. A very similar effect has been produced by the Chinese win-win approach that encourages economic cooperation benefiting both sites, no matter what the partner’s domestic regime is like. In other words, in an anarchy one’s hesitation becomes a benefit for his rival. U.S. hesitations, or more precisely, ideological prejudices, became the underlying structural factor of the last decade as it fostered shifts in the power distribution within the structure of international relations. These shifts have been noted by many experts (Mearsheimer, 2018; McDonald and Parent, 2018; or Wohlforth and Brooks, 2016). As the Composite Index of National Capabilities for the year 2018 shows (see Fig. 3), the U.S., China, the EU, and India were materially prevalent actors in the international structure. Considering the current economic setbacks, China is likely to increase its material dominance, while the structural shifts that were evident in 2018 are likely to deepen. Hence we can state that the shifts in the status quo, global pandemic and magnifying economic crisis are the main structural effects that are influencing international affairs today. Then the question arises: How exactly will the crises of 2020 influence international affairs?

Figure 3. 2018 Composite Index of National Capability

The Pandemic and Economic Crises

Can pandemics be avoided? The answer is no. Pandemics are here to stay. Deadly diseases have been known for their dangerous effects for thousands of years. Plagues ravaged ancient civilizations, the world in the Middle Ages, and in 1918-1920. The Spanish flu outbreak alone caused the death of 50-100 million people, that is, 2.7-5.4% of the world population. The global pandemics are a feature of human history and will remain as such. Many scholars believe that the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic caused the Great Depression (Garret, 2007; Barro and Ursua, 2009), while the latest example of H5N1 crises illustrates the destructive potential for services, transportation, and tourism. The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is indisputable, and one of its direct consequences is, undoubtedly, deglobalization, which will certainly change the perception of the global economy and the system of international affairs as we know it. Some even think that the current situation can potentially unleash an economic catastrophe similar to the Great Depression (Bloomberg, 2020).

The economic crises influence everyday international life, and therefore have the potential to change the international structure or accelerate ongoing changes. A graphic example is the London Credit Crisis of 1772 that is often seen as connected with the Boston Tea Party and the subsequent American War for Independence (Bondarenko, 2020). All authors supporting the premise that economic crises can potentially affect the entire international structure connect the Great Depression during the interwar period with the decline of Pax Britannica, and the more recent works attribute the decline of Pax Americana to the financial crisis of 2008/09 (Sally, 2011).

Such changes in ideology cause changes in the states’ internal political structure, foreign policy behavior of unitary actors, and the political maps of the continents.

The impact of the 2020 crises is not reflected in the structure of international relations yet; however, drawing on the recent dynamics, we can state that the international structure began to change before 2020. The decline of the U.S.-led liberal order, the rise of China, Russia’s reviving great power status, and the European Union’s recent failures have been at the center of academic discourse for over a decade already. This proves that the change in the global status quo is now unquestionable.

Debating Possible Configurations

Recent history has proven once again that no international structure lasts forever, not even if it has overwhelming material supremacy, such as that the U.S. enjoyed during its “unipolar moment.” As has been shown above, the downfall of Pax Americana resulted in a period of nonpolarity, with the international structure displaying characteristics of both nonpolar and polar configurations. If we assume that the structure may possess both multipolar and nonpolar characteristics, we may be facing a hybrid of the two configurations or the nonpolarity configuration as a temporary consequence of power redistribution with the potential for a new structure to emerge in the near future. So, it seems feasible to outline basic conditions for the present international structure to remain in the current state or shift towards multipolarity or, alternatively, bipolarity.

The contemporary structure of international relations will remain nonpolar if:

- The U.S. continues to decline, which will trigger further diffusion of power;

- Other actors are unable to counterbalance the U.S., China, or the EU;

- The great powers lack the ambitions or capabilities to alter the status quo (disorder);

- The centers of meaningful power remain independent in their foreign policies;

- The global political system sees further erosion of international law and institutions.

The international structure will shift towards multipolarity if:

- The U.S. continues to decline;

- China continues to rise;

- Russia sustains its great power status;

- The EU pursues strategic political autonomy notwithstanding the return of Democrats to the White House, and eventually, India and Brazil become system-wide powers;

- A group of great powers try to alter the existing status quo;

- Great powers engage in balancing behavior (continue the pre-COVID-19 behavior).

The international structure will shift towards bipolarity if:

- The U.S. overcomes the internal crisis;

- China continues to rise;

- China and the U.S. form regional orders;

- Both engage in balancing behavior;

- Other powers remain relatively important, but not on a par with the U.S. or China.

* * *

The results of the study presented in this paper demonstrate that the crises of 2020 will boost the shifts in the global status quo that started earlier. China is expected to continue to lead in the economic growth, with the global economy hit hard by the crises and shrinking by approximately 4.4 percent. The Western economies are expected to suffer the worst. Obviously, the pandemic will impact globalization as we know it; moreover, the 2020 crises may cause deglobalization.

Owing to their outstanding material and military capabilities built before 2020, the U.S., China, India, the EU, and Russia are most likely to take the highest ranks in the newly born structure of international relations. Today, however, it is showing signs of nonpolar diffusion of power, disorder, and increased relevance of non-state actors, on the one hand; and the return of great power competition and balancing behavior typical of bi-, tri- and multipolar structures, on the other hand. Mixed structural characteristics point to the fact that we are witnessing a unique new global configuration with the great power relations at the top and the vastly dispersed power at the bottom of the system. Nonpolarity is a phenomenon occurring during the transition from unipolarity with extreme concentration of power towards a new power configuration.

In the post-COVID-19 disorder, the West will remain the most influential center of power, although we will witness a significant waning of its power and influence. Thus, it is unlikely that any of the great powers in the system will be capable of establishing an institutionalized global order, similar to the previous one.

In global emergencies, great power competition is an unwelcomed behavior as the current challenges require a firm and coordinated global response for addressing severe epidemic challenges and subsequent economic setbacks. The West is yet to bear the international consequences caused by the economic crisis, while the worst humanitarian and economic setbacks will presumably hit the Third World countries, which will need assistance from the wealthy North.

Acemoglu, D., 2020. The Coronavirus Exposed America’s Authoritarian Turn. Foreign Affairs, 99(2) [online]. Available at: <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2020-03 23/coronavirus-exposed-americas-authoritarian-turn> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Allison, G., 2020. Destined for War. Melbourne: Scribe.

Barro, R.J, and Ursua, J.F., 2009. Pandemics and Depressions. The Wall Street Journal [online]. Available at: <https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB124147840167185071> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Bondarenko, S., 2020. Five of the World’s Most Devastating Financial Crises. Encyclopedia Britannica [online]. Available at: <www.britannica.com/list/5-of-the-worlds-most-devastating-financial-crises> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Brooks, S. and Wohlforth, W., 2018. America Abroad. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bratersky, M., 2020. Daleko li do voiny? [Are We Far Away From War?]. Rossiya v global’noi politike, 18(3), May/June [online]: Available at: <globalaffairs.ru/articles/daleko-li-do-vojny/> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Bystricky, A., 2020. Coronavirus Instead of Great Power War: Will the Global Order Change? Valdai Club. Available at: <https://ru.valdaiclub.com/a/chairman-speech/koronavirus-vmesto-voyny/> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Campbell, K.M and Doshi R., 2020. Coronavirus Could Reshape Global Order. Foreign Affairs. 99(2) [online]. Available at: <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2020-03-18/coronavirus-could-reshape-global-order [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Deutsch, K. W. and Singer, J. D., 1964. Multipolar Power Systems and International Stability. World Politics, 16(3), pp.390-406.

European Commission, 2016. EU Global Strategy. EEAS. Available at: <https://eeas.europa.eu/topics/eu-global-strategy_en> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Elagina, D., 2021. Vladimir Putin’s Approval Rating in Russia monthly 1999-2021. Statista, 4 February [online]. Available at: <https://www.statista.com/statistics/896181/putin-approval-rating-russia/> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Gabriel, S., 2018. In a World Full of Carnivores, Vegetarians Have a Very Tough Time of It. German Federal Foreign Office, 5 January [online]. Available at: <https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/newsroom/news/gabriel-spiegel/1212494> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Garret, T. 2007. Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Implications for a Modern-Day Pandemic. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis [online]. Available at: <https://www.stlouisfed.org/~/media/files/pdfs/community-development/research-reports/pandemic_flu_report.pdf> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Gonzalez, M., 2020. Global Trends Home Page [online]. Dni.gov. Available at: <https://www.dni.gov/index.php/global-trends-home> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Gopinath, G., 2020. The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since the Great Depression. IMF Blog. Available at: <https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/the-great-lockdown-worst-economic-downturn-since-the-great-depression/> [Accessed February 8, 2021].

Green, M. and Medeiros, E., 2020. The Pandemic Won’t Make China the World’s Leader. Foreign Affairs, 15 April [online]. Available at: <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-04-15/pandemic-wont-make-china-worlds-leader> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Grunstein, J., 2020. Why the Coronavirus Pandemic Won’t Lead to a New World Order. World Politics Review, 1 April [online]. Available at: <https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/insights/28646/why-the-coronavirus-pandemic-won-t-lead-to-a-new-world-order> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Haass, R., 2008. The Age of Nonpolarity. Yaleglobal Online [online]. Available at: <https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/age-nonpolarity> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Haass, R., 2018. A World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order. New York: Penguin Books.

Ikenberry, J., 2018. The End of Liberal International Order? International Affairs, Vol 94(1), pp.7–23. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix241>

IMF, 2020. World Economic Outlook, October 2020: A Long and Difficult Ascent. Available at: <https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/09/30/world-economic-outlook-october-2020> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Jervis, R., 2020. Foreign Policy of the U.S. Nepal Institute for International Cooperation and Engagement. Available at: <https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=832812267527595>

Keohane, R.O., 2020. Understanding Multilateral Institutions in Easy and Hard Times. Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 23:1-18 [online]. Available at: <https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050918-042625> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Kopalyan, N., 2017. World Political Systems After Polarity. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Krejčí, O., 2020. The Chinese Miracle. Argument Journal [online]. Available at: <http://casopisargument.cz/2020/03/23/cinsky-zazrak/> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Lague, D. and Lim, B., 2019. Special Report: New Missile Gap Leaves U.S. Scrambling to Counter China. Reuters, 25 April [online]. Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-army-rockets-specialreport-idUSKCN1S11DH> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Layne, C., 2009. The “Poster Child for Offensive Realism”: America as a Global Hegemon. [online]. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232926760_The_Poster_Child_for_offensive_realism_America_as_a_global_hegemon> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Lukyanov, F., et al., 2020. Staying Sane in a Crumbling World. Russia in Global Affairs, 14 May [online]. Available at: <https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/staying-sane-crumbling-world/> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Macaes, B., 2020. China Wants to Use the Coronavirus to Take Over the World. National Review, 3 April [online]. Available at: <https://www.nationalreview.com/2020/04/coronavirus-pandemic-china-seeks-increase-geopolitical-power/> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Macdonald, Paul K. and Parent, Joseph M., 2021. Twilight of the Titans: Great Power Decline and Retrenchment. S.l.: Cornell University Press.

Mearsheimer, J.J., 2014. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton.

Mearsheimer, J.J., 2018. Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities. Yale University Press.

Monteiro, N., 2011. Unrest Assured: Why Unipolarity Is Not Peaceful. MIT Press Journals. Available at: <https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/ISEC_a_00064> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Moravcsik, A., 2020. Why Europe Wins. Foreign Policy, 24 September [online]. Available at: <https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/24/euroskeptic-europe-covid-19-trump-russia-migration/> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

National Intelligence Council, 2012. Global Trends 2030. Available at: <https://www.dni.gov/index.php/who-we-are/organizations/mission-integration/nic/nic-related-menus/nic-related-content/global-trends-2030> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Nye, Joseph, Jr, 2020. No, the Coronavirus Will Not Change the Global Order. Foreign Policy, 16 April [online]. Available at: <https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/16/coronavirus-pandemic-china-united-states-power-competition/> [Accessed January 28, 2021].

Russian National Security Strategy, 2015. Available at: <http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/OtrasPublicaciones/Internacional/2016/Russian-National-Security-Strategy-31Dec2015.pdf> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Organski, A. F. K. and Kugler, J.,1980. The War Ledger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Osterholm, Mikael, 2005. Preparing for the Next Pandemic. Foreign Affairs. Available at: <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2005-07-01/preparing-next-pandemic> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Pew Research, 2020. Partisan Antipathy: More Intense, More Personal. Available at: <https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/10/10/partisan-antipathy-more-intense-more-personal/> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Posen, Barry., 2015. Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy. Cornell University Press.

Sally, R., 2011. The Crisis and the Global Economy: A Shifting World Order? European Centre for International Political Economy [online]. Available at: <https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/the-crisis-and-the-global-economy-a-shifting-world-order.pdf> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Schweller, Randall L. and Xiaoyu Pu., 2011. After Unipolarity: China’s Visions of International Order in an Era of U.S. Decline. International Security, 36(1), pp.41–72. JSTOR [online]. Available at: <www.jstor.org/stable/41289688> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Shakleina, T., 2012. Velikiye derzhavy i regional’nye podsistemy [Great Powers and Regional Subsystems]. Available at: <http://intertrends.ru/system/Doc/ArticlePdf/566/Shakleina-26.pdf> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Shambaugh, D., 2015. China’s Soft-Power Push: The Search for Respect. Foreign Affairs, 94(4), pp.99-107. Available at: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/24483821> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Shalal, A., 2020. Chinese Economy Normalizing But Stark Risks Remain: IMF. Reuters [online]. Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-imf-china/economy-normalizing-in-china-after-coronavirus-peaked-stark-risks-remain-imf-idUSKBN2171QK> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Singer, J. David, Bremer, S. and Stuckey, John, 1972. Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 1820-1965. In: Russett, B. M. (ed.) Peace, War and Numbers. Beverly Hills: Sage, pp.19-48.

Tereszkiewicz, F., 2020. The European Union as a Normal International Actor: An Analysis of the EU Global Strategy. International Politics, 57, pp. 95–114. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-019-00182-y> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Xuetong, Y., 2015. Why a Bipolar World Is More Likely Than a Unipolar or Multipolar One. New Perspectives Quaterly, 28 July.

Walt, Stephen M., 1987. The Origins of Alliances. Cornell University Press. JSTOR [online]. Available at: <www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt32b5fc>

Walt, S., 2020. The United States Can Still Win the Coronavirus Pandemic. Foreign Policy, 3 April [online]. Available at: <https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/03/united-states-can-still-win-coronavirus-pandemic-power/> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Waltz, K. N., 1993. The New World Order. Millennium, 22(2), pp.187–195. DOI: 10.1177/03058298930220020801.

Wilkinson, David, 1987. Central Civilization. Comparative Civilizations Review, 17(17) Fall, pp.31-59 [pdf]. Available at: <https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1130&context=ccr> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Wilkinson, David, 1999. Unipolarity Without Hegemony. International Studies Review, 1(2) Summer, pp.141-172. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1111/1521-9488.00158> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Winger, E., Shulyatyeva,Y., Husby, A. and Riccadonna, C., 2020. The US Economic Recession Tracker. Bloomberg. Available at: <https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/us-economic-recession-tracker/> [Accessed 28 January 2021].

Wohlforth, William C., 1999. The Stability of a Unipolar World, International Security, 21(1) Summer, pp. 5-41.

World Health Organisation, 2019. A World at Risk: Annual Report On Global Preparedness for Health Emergencies. Available at: <https://apps.who.int/gpmb/assets/annual_report/GPMB_Annual_Report_Exec_Summary_Foreword_and_About_English.pdf> [Accessed 28 January 2021].