Social phenomena do not usually occur suddenly but ripen gradually. Often social manifestations hide behind seemingly insignificant fashionable trends. The fear of war in recent years is revealed in worried, although almost invisible, attitudes expressed during opinion polls. Concurrently, a military style trend has slowly but steadily entered everyday life: paintball and shooting sports are incredibly popular; teenage girls wear combat boots, camouflage clothing, and dog tags. Indeed, T-shirts with images of “Polite People” and the Iskander and Topol missile systems are in high demand. If we put these fashion trends into the context of the nationwide celebrations of the 70th anniversary of the victory in World War II, the military theme is hard to miss.

This sentiment of anxiety emerged gradually and initially was visible only to specialists and the most observant commentators. But in 2014-2015 the mass media began to hype the theme “Russians are afraid of a major war again.” The Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM) recently published new data: “The fear index measuring the fear of international tensions increased by 10 points between July and October, reaching a record high of 20 points over the last ten months. Sixty-two percent of Russians described international conflicts as a real threat.”

My observations are consonant with a Facebook post by journalist Katerina Gordeyeva. With her permission, I am publishing a quote from this post. We both belong to the same generation and have similar feelings: “When I was a little girl, TV programs were organized in such a way that bleak movies about the previous war were immediately followed by the Vremya news program. It did not relate things straight to the point; instead, the program instilled fear of an ominous build-up of nuclear potentials and the inevitability of a future war. I was very scared. I was so afraid that often on my way home from school I thought an ambulance siren was an air raid warning and ran for my life towards the nearest underground pedestrian crossing. In my dreams at night bombs fell from the sky, nuclear mushroom clouds rose over my neighborhood, and my relatives, neighbors, and strangers sought but could never find a place to hide. I screamed and woke up in tears. Later, when I grew up and began working, it turned out that war in close-up was disgustingly dirty [expletive]; it was still scary but in a different way. Yet the panic from my childhood was gone. I thought it would never return, but now it is back.”

To better understand what is happening among the Russian public consciousness concerning war, we should look at how public sentiment has changed over the last thirty years. But first I will discuss the basic notions of ‘war’ and ‘fear.’

War and Fear

The notion of ‘war’ belongs to the core of Russian linguistic consciousness. It is an important way to understand the world, yet not the most common one (73rd place out of 75 key notions in linguistic consciousness, according to the Russian Associative Dictionary, edited by Yury Karaulov). In Russian, ‘war’ is a polysemantic word, just like in English. The Russian Associative Dictionary contains a variety of associative reactions to the stimulus word ‘war’ (respondents are usually asked to name the first few words that come to mind). The most common association is the opposite notion of ‘peace’—an allusion to Leo Tolstoy’s novel War and Peace. Overall, however, association words prevail with a negative connotation (death, scary, horror, cruel, grief, blood, fear, destructive, smoke, terrible, horrible, bloody, etc.). In more specific terms, people overwhelmingly name the Great Patriotic War rather than a world, civil, or nuclear war. The poll was held in the 1990s, thus there were many associations with Chechnya, the Chechen war, and the recent Afghan War.

Psychologists and sociologists place the fear of war among the most common (mass) fundamental fears (the so-called existential fears relating to human existence). At the same time, the fear of war is directed at a specific object, usually pointing to the source of danger, as seen in the example of the association field of the word ‘war.’

The term ‘fear’ in this article is used in the generalized sociological perspective and as applied to public opinion polls. Pollsters only fix respondents’ statements that they are afraid of something. As a basic understanding of the term, this article uses the definition provided by well-known researchers of fears in Russia, Vladimir Shlapentokh and his colleague Susanna Matveyeva: Fear is “a signal of potentially negative developments, events, or processes; it is a permanent feature of human life; and it is compensated for by various ‘overlapping’ mechanisms that facilitate and even suppress this feeling.”

Soviet Catastrophism

Memories of the war, “the struggle for peace,” and the fear of a possible new war were key elements in the Soviet ideology of mobilization in the 1960s-80s, and a surefire way to shape the identity of the Soviet/Russian people. For understandable reasons we do not have direct sociological data for that period. However, the results of an opinion poll conducted by VTsIOM in 1989 show that the fear of war was at the time almost central and second only to fears about the health of a person’s relatives (Fig. 1).

The personal experience of World War II stood at the core of the Soviet people’s fear of war. This was first-hand fear imbued with personal or family memories. Another source of fear was second-hand information—reminiscences of other people, representations of the war in art, and, of course, a well-organized propaganda machine. The image of the war combined personal and collective memories of the war and ideologemes. In time, the layers mixed and formed a collective historical memory of the war—a complex mechanism of regulating mass consciousness. The collective memory of the war is not only emotional and deeply symbolic, but also very mobile: it is constantly formed and manipulated by the context of the present. The major official leitmotifs of the image of the war were its epochal nature, the struggle for the very existence of the Soviet people, the victory over Nazism and saving the world, heroism, tragedy, and the demonstration of the advantages of the socialist system and its values. All these elements are present in Russia today, especially in recent years.

Psychologists assess memories of the war in the context of post-traumatic consciousness and distinguish the stages of shock (war), negation (post-war years), awareness (1960s-1970s), and recovery (1980s-1990s) (Lyubov Petranovskaya). For this article, it is important to note that allusions to the theme of war may be visible and sensitive for the collective consciousness, still imbued with war trauma and pain. However, the present military leitmotif hurts people to a lesser extent: the stage of collective recovery from injury is marked by detachment, rationality, or demonstrative behavior verging on the carnivalesque (St. George ribbons, car stickers reading “Thanks to grandpa for the victory,” “To Berlin!,” etc.).

The Great Patriotic War still remains the subject of the collective consciousness. But now, at the stage of moving further and further away from the war and of relative emotional calm, feelings of joy and pride emerge rather than suffering. The responses of Russians when asked to name associations that come to mind when they hear “Great Patriotic War” are very indicative: the joy of victory, Victory Day (27%), pride in the country and people (26%), sorrow, grief, pain, tears (18%), death, loss of life (13%), hard times, suffering (7%), fear, terror (7%), and long war, fighting, bombings (6%) (Public Opinion Foundation, 2015).

In addition, the bitter confrontation between the Soviet Union and the West, the arms race, and the threat of nuclear war all contributed to the fear of war among the Soviet people. In other words, the fear of war had two time frames: the past and the present. The image of the past war, combined with concern for the future of the world and a desire to prevent nuclear war, was the main foundation of Soviet catastrophism (“Anything but war,” “Look what is happening in the world,” “No, son, there will be no war, but there will be such a struggle for peace that no stone will be left standing in the entire world”). It is indicative that one of the first public opinion polls in the Soviet Union, conducted by Boris Grushin in 1960, was called “Will Humanity Be Able to Prevent a World War?”

According to psychological surveys, the Soviet fear of nuclear war was less pronounced than in the United States, where nuclear phobia paralyzed millions of people, regardless of their age, level of education, and awareness of the situation. An opinion poll conducted by VTsIOM in 1996 showed that the possibility of nuclear war incited “strong fear” among 29 percent of respondents and “constant fear” among 8 percent. Apocalyptic sentiments regularly feature in opinion polls. For example, 14 percent of Russians are confident that civilization will be destroyed not by external factors, but that it will destroy itself in a nuclear world war (Public Opinion Foundation, 2011). Or, for example, respondents describe their fears of nuclear war in the following way: “There are more chances that the end of the world will come,” “The world may disappear,” “The Apocalypse will come,” “All this may destroy our civilization,” “There is a threat of mankind’s destruction,” “There is a high probability of self-destruction,” “If nuclear weapons are used, there will be nothing alive left on Earth,” “The Earth may explode at any moment,” “A horrible war may break out at any time,” “And what if a war begins? (Nuclear) weapons could be used then,” and “I’m afraid of nuclear war” (Public Opinion Foundation, 2013, answers to the question “Why do you think it is bad that the number of nuclear powers is growing?”).

Finally, the last major layer of Soviet catastrophism is the trauma of the Afghan War. Sociologists often hear the following allusions to it from respondents, mostly women: (On a possible war with Georgia) “It’s a pity when our men have to die,” “Why expose our sons to danger?,” “Both the Chechen and Afghan wars were useless; now it will be the same and our young people will die there,” “Our sons suffer from other people’s conflicts,” “There are many victims among peacekeepers,” “I wish our sons did not have to die for somebody else’s interests,” “I wish there were fewer victims among Russians,” and “Our sons will again die for nothing” (Public Opinion Foundation, 2008); (On a possible war with North Korea) “Russia will be a peacemaker and will send troops,” “Our sons will have to fight again,” “Russians will also be there like in Afghanistan,” and “Our sons will die again” (Public Opinion Foundation, 2013).

It is noteworthy that ordinary people’s statements about local wars clearly reveal their negative attitudes to them and conviction that “we” are being involved in the war—by both enemies and the Russian government (somebody else’s interests, will be involved, will have to fight, exposed to danger, interfere, and get into a mess).

Post-Soviet Catastrophism

A comparison of VTsIOM opinion polls in 1989 and 1994 shows a gradual decrease in the fear of war. In the 1990s, social and economic fears (of crime and poverty) were dominant:

Data from VTsIOM opinion polls in 1989 and 1994. The data were published in the article “Fear as a Framework for Understanding the Present,” by L. Gudkov.

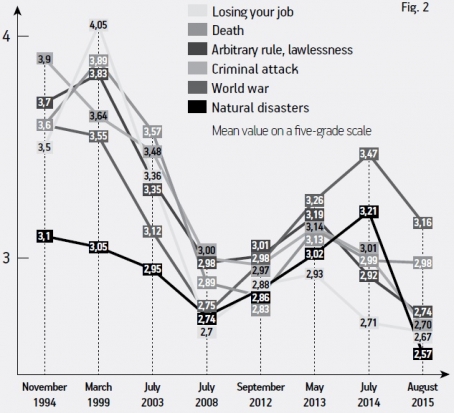

Also indicative are the dynamics of responses to the question “Are you afraid of… and to what extent?” (on a five-grade scale), published by the Levada Center (polls conducted between 1994-2015) (Fig. 2). As follows from the diagram, the fear of war gradually decreased from 1994 to 2008, while the fear of losing one’s job, a criminal attack, or arbitrary rule increased.

Fig. 2 Responses to the question “Are you afraid of … and to what extent?” (average grade on a five-grade scale). Levada Center nationwide representative opinion polls. Each poll involved 1,600 respondents

Source: Levada Center

The polls show that the mobilization-type Soviet catastrophism in the 1990s gave way to more personal fears: economic and social (crime, unemployment, injustice, etc.), and technological, environmental, family, and personal fears (loneliness, failure to realize one’s potential, etc.). However, the fear of war was not completely absent. In part it was “frozen,” revealing itself periodically in answers to questions about the future of humanity or local threats. Partly, the phobia of war transformed into the fear of terrorism as an internal Russian war. For example, in 2000-2001, more than 70 percent of Russians were convinced that the Chechen war was still going (Public Opinion Foundation); in 2004, following recent terrorist attacks, about 40 percent of respondents agreed with the statement that a war had been declared on Russia (Public Opinion Foundation, 2004).

Some people were concerned about a possible war because of the events in Georgia and the presence of U.S. military experts there. For example, in 2002, a small part of the population was afraid of a “direct invasion” of Americans into Russia (8%): “They will soon enter Moscow” and “They want to conquer us” (Public Opinion Foundation, 2002). In 2008, the events in Georgia and South Ossetia once again triggered fears of a possible war. Although the majority of Russians supported the government’s policy, some expressed concern (5%).

In 2008, when asked by the Public Opinion Foundation “What negative consequences will recognizing South Ossetia’s independence by the Russian authorities have for Russia?,” respondents gave the following answers: “A possibility of a military conflict;” “War is possible;” “If something happens, our sons will have to die again;” “There will not be peace;” “There will be a war with Georgia;” “Hostilities will resume;” “War may start again;” “Georgians may start a war;” and “There will be another Chechnya.”

So, in post-Soviet society the fear of war has abated, but has not disappeared, especially among the older generation. In fact, the fear of war cannot disappear because it serves as a universal filter for understanding the world. This filter is black-and-white and emotional, and always offers a habitual and understandable picture of reality.

Today: “fear is back”

The years 2012-2014 marked a turning point because they revived the fear of war. As a consequence, in Russia there are growing political ratings, a positive attitude towards the army, a rise in patriotic sentiment, a feeling of pride in the country, and the possibility of declaring that Russia is a great power. Simultaneously, anti-Western sentiment is more pronounced, and people’s circles of friends and enemies are changing. In 2014-2015, the percentage of people complaining about the deterioration of their financial position and expressing economic fears increased significantly.

All sociological centers observe a growing fear of (world/nuclear) war and military conflicts (Public Opinion Foundation, VTsIOM, Levada Center). I have already cited above data from VTsIOM and the Levada Center. A recent poll conducted by the Public Opinion Foundation has shown that the fear of attacks from other countries has increased from 11 percent in 2000 to 31 percent in 2015. These figures are very volatile, as they depend on events, media rhetoric, and fatigue over certain topics, for example, Ukraine.

The current public attitude towards war is a very complex, contradictory, and insufficiently explored phenomenon. Obviously, public opinion polls are not the best way to debate this sensitive topic. Focus groups, interviews, or analyses of statements on the Internet are more adequate methods. Yet opinion polls show the fragility and inconsistency of many attitudes towards war. Currently, it is tentative catastrophism or, using the terminology of Shlapentokh, catastrophism of judgments but not action. It is hard to predict what will happen next.

Let us take such a complex issue as the assumption of Russia’s participation in military operations in Ukraine. Such views exist, but they are not dominant. According to VTsIOM, in January 2015 only 20 percent of Russians supported Russia’s military involvement in Ukraine to stop the military conflict. Polls conducted by the Levada Center showed a similar figure (17 percent). No more than one-third of Russians (about 25 percent according to VTsIOM’s February data, and 30 percent according to the Levada Center’s August data) thought that the armed clashes could escalate into a war between Russia and Ukraine. Yet the majority of Russians fear the prospect of war with Ukraine and its escalation into a global conflict.

Syria is an even more complex issue. Most Russians (66 percent, VTsIOM) supported President Putin’s decision to send military aircraft to Syria to attack the Islamic State’s positions. At the same time, more than a half of respondents said “it is better not to get involved in military conflicts; then we’ll have fewer enemies” (52 percent). As we can see, the negative assessment of the Afghan experience is still strong in people’s minds. The poll also shows that not all Russians understand the meaning of what is going on in the Middle East, the balance of power in the region, and who should be supported (it is noteworthy that women and older people fear war to a greater extent and are less supportive of Russia’s military action).

- From the research we can distinguish the following three models of the fear of war: Soviet catastrophism (a painful rethinking of the Great Patriotic War + the existence of a list of enemies + concern about the future of the world + the struggle for peace).

- Post-Soviet latent catastrophism (painful rethinking of the Great Patriotic War + rapprochement with former enemies + situational suspicions about former enemies + concern about an individual’s destiny and economic survival).

- Present catastrophism (ritual rethinking of the Great Patriotic War and its glorification + anti-Western sentiment + growth of patriotism and isolationism + growth of the fear of war).

The fear of war today is a heavy burden on the public consciousness. On the one hand, it is developing amid a so-called hybrid war. Public consciousness has difficulty comprehending the present situation and does not understand whether or not there is a war in Donbass, what is going on in Syria, and how to connect these processes. Since the geopolitical situation is very difficult to understand, public consciousness dodges reality and lives on former myths and images (which, by the way, are widely exploited by the media). On the other hand, these former Soviet images can be very traumatic (as in the aforementioned Facebook post by Katerina Gordeyeva). Appealing to world war traumas may increase rejection and fear as “a signal of a potentially negative development” (Shlapentokh); but it can also make this anxiety habitual—like a chronic pain familiar from childhood. And, finally, the most difficult part; a “television war,” despite its disturbing and gradually annoying images, makes viewers accustomed to bright impressions. Images of war can evoke mixed emotions in people, including approval and emotional involvement in the process. This is especially true of young people who do not have the traumatic experience of the Cold War.

Hardly anyone can tell how the fear of war will develop in such a complex, multifactorial situation—whether it will gradually disappear, evolve into an obsessional phobia, or meet with a desire to preserve the status quo of the “fat and comfortable” 2000s. Let’s hope for the best-case scenario.