There is a widespread belief both in Russia and abroad that the Ukrainian crisis has undermined the system of international relations, which was built after the end of the Cold War at the turn of the 1990s and even since much earlier—after the end of World War II in 1945. This belief is corroborated with impressive analogies.

The bone of contention then was the division of postwar Europe between the Soviet Union and the U.S. Now it is the struggle for influence in the post-Soviet area and in its second largest country after Russia—Ukraine. In former days, the geopolitical conflict took place amid the irreconcilable ideological confrontation between communism and capitalism. Now, after twenty years of oblivion, the ideological schism has again come to the fore—this time between spiritual values of Russian conservatism and Western liberalism (which is associated with same-sex marriages, legalization of drugs and prostitution, and mercantile individualism). This association is further strengthened by an unprecedented growth of great-power sentiment and creeping immoral and pernicious rehabilitation of Stalinism in Russia, as well as by the irresponsible U.S. policy of exporting American canons of freedom and democracy to pre-capitalist countries.

It is hard to escape the impression that today, at the beginning of the 21st century marked by globalization and information revolution, the world is returning to seizure of territories and geopolitical wars that were characteristic of the first half of the 20th century and even of the 19th century. True, the world order that is now falling to pieces is far from perfect, and Russia, like many other countries, has reasons to complain about it. Yet it is far from evident that the next world order will be better. And it is far from clear what the essence of the world order that is now gone was and whether a new edition of the Cold War is possible.

A COLD-WAR WORLD AND ORDER?

The system of international relations is not based on international law and institutions, but rests on the actual distribution and balance of power between major nations, their alliances and common interests. This is what determines how effective and practicable the international law and its mechanisms are. The period after the end of WWII was the most vivid example of that.

The world order of those times was built on the accords reached by the victorious countries in Yalta, Potsdam and San Francisco in 1945. The accords drew borders in Europe and the Far East where the German, Italian and Japanese empires had collapsed; they established the United Nations and resolved many postwar issues. The big idea was that the great powers would jointly maintain peace and resolve international disputes and conflicts on the basis of the UN Charter in order to prevent a new world war. But that world order was never built—it quickly crumbled amid the confrontation between the USSR and the United States in Europe and then worldwide.

In Central and Eastern Europe liberated by the Soviet army, the Soviet Union within a few years established a socialist regime and initiated mass repressions. This outraged the United States which, in turn, helped suppress the communist movement in several West European countries. The occupation zones in Germany turned into two states—the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic. The establishment of NATO and the admission of West Germany into it were reciprocated by the creation of the Warsaw Pact. Over time, the confronting parties deployed forces unprecedented in strength for peacetime and thousands of nuclear warheads on both sides of the Inner German border.

Important European borders—between the GDR and Poland (the Oder-Neisse line), between West and East Germany, and the Soviet Union’s border around the Baltic States—were not legally recognized by the West; in the first case until the 1970 agreements, in the second case until 1973, and in third case ever. The status of West Berlin became a source of several dangerous crises (1948, 1953 and 1958). The Berlin crisis of August 1961, when Soviet and U.S. tanks actually faced each other at point-blank range, almost led to an armed conflict between the USSR and the U.S. The Berlin issue was resolved only by agreements of 1971. The Cold War paralyzed the UN Security Council and turned the organization from an institution for maintaining international peace and security into a forum for propaganda polemics.

Ready-for-use nuclear arsenals gave rise to fear of a head-on clash in the area of ??direct military confrontation between the two powerful alliances, which forced the confronting parties to freeze conflicts and the actual borders in Europe (but made their “unfreezing” inevitable after the end of the Cold War). Yet during the first twenty-five years of that world order the European continent was constantly shaken by tensions and crises between the two blocs. Simultaneously, the Soviet Union militarily suppressed civilian and armed uprisings in the socialist camp (in 1953 in East Germany, in 1956 in Hungary, and in 1968 in Czechoslovakia).

The situation was relatively stabilized more than twenty years later—during the first temporary detente between the two nuclear superpowers, codified in the ABM and SALT I treaties of 1972. Three years after that, in 1975, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) signed the Helsinki Final Act, which proclaimed the inviolability of national frontiers in Europe and ten principles of peaceful coexistence of European nations (including territorial integrity, sovereignty, non-use of force, and the right to self-determination of peoples).

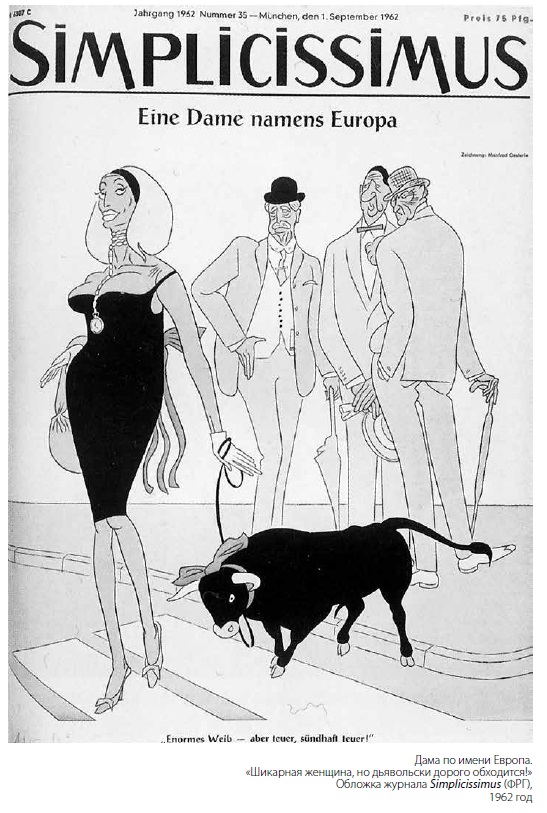

A lady by the name of Europe.

“A gorgeous woman, but costs a real fortune.”

The front cover of Simplicissimus magazine (Germany), 1962

Outside of Europe, however, the Cold-War world order manifested itself in the absence of order up until the end of the Cold War. For forty years the world lived in constant fear of a global war. In addition to the Berlin crisis of 1961, great powers at least three times were on the brink of nuclear catastrophe: during the Suez crisis of 1956, during the Middle East war of 1973, and during the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, when the red line was nearly crossed. Moscow and Washington reached a compromise just a couple of days before the date when the U.S. planned to deliver an air strike against the Cuban bases where Soviet nuclear missiles had been placed. Some of those missiles were brought to combat readiness for a retaliatory strike, which Washington did not know. Mankind was saved then not only by the caution displayed by the Kremlin and the White House but also by sheer luck.

There was no joint global governance by the two superpowers—it was just the fear of a nuclear catastrophe that caused the confronting parties to avoid direct clashes in their geopolitical rivalry. Nevertheless, over that period, dozens of large regional and local wars and conflicts occurred, taking the lives of over 20 million people. U.S. military casualties in those years amounted to 120,000 people, as many as in World War I of 1914-1918. Often conflicts broke out suddenly and ended unpredictably, with the great powers suffering defeat—the Korean War, two wars in Indochina, five wars in the Middle East, a war in Algeria, wars between India and Pakistan, and between Iran and Iraq, wars in the Horn of Africa, the Congo, Nigeria, Angola, Rhodesia, and Afghanistan, not to mention countless internal coups and bloody civil wars.

In their global rivalry, the parties arbitrarily violated international law, including territorial integrity, sovereignty and the right of nations to self-determination. Military force and subversive operations were used regularly, cynically and massively under ideological banners. Outside Europe, the borders of states constantly changed, military force was used to break up and reunify countries (Korea, Vietnam, the Middle and Near East, Pakistan, the Horn of Africa, etc.). Almost in each conflict the United States and the Soviet Union were on opposite sides and provided direct military assistance to their allies.

This rivalry was accompanied by an unprecedented race in nuclear and conventional weapons, armed confrontation of the superpowers and their allies on all continents and in all oceans, as well as by the development and testing of space weapons. This rivalry caused huge economic costs to all countries, yet it especially undermined the Soviet economy. It was only in 1968 that the parties signed the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), and in the late 1960s they began serious negotiations on nuclear weapons and, later, on conventional armed forces in Europe.

The world economy was divided into two systems: capitalist and socialist. In those circumstances, it was impossible to use economic sanctions against each other because there were constant and rigid trade barriers (such as COCOM). It was only in the 1970s that the parties launched selective economic interaction—hydrocarbon exports from the Soviet Union to Western Europe, and modest imports of industrial goods and technologies from there. Economic crises in the West caused joy in the East, while economic difficulties experienced by the USSR were pleasant news to the United States and its allies. On the other hand, economic independence (autarky) and reliance on the defense industry as a development engine expectedly drove the socialist economy into an economic and technological stupor.

The forty years of the bipolar system of international relations and the Cold War vividly demonstrated that international law and institutions work only as an exception—in those rare cases when major powers realize their common interest. Otherwise, zero-sum games turn this law and these organizations into nothing but means to justify one’s actions and forums for propaganda battles.

Since the late 1990s Russia has been living with a sense of growing threat. It has been stated even officially that the end of the Cold War did not strengthen but weakened the country’s national security. This is a pure and simple political and psychological aberration. Partly it is explained by the fact that when the most terrible threat—the probability of a global nuclear war—moved far into the background, universal harmony did not emerge, despite naive hopes of the early 1990s. The horrors of the forty years of the Cold War made ??everyone forget how dangerous the world had been earlier and that there had been two world wars. Moreover, nostalgia for the leadership positions once held by their country—as one of the two global superpowers—causes many people in Russia, those who worked during the Cold War and especially those who came into politics after it, to substitute reality with historical myths and have regrets about the lost “world order” which in fact was mere balancing on the brink of total destruction.

A NEW WORLD ORDER

As often happens in history, the fundamental change in the balance of power in the world arena was accompanied by changes in the world order, however dubious the term may look in reference to the Cold War period. The collapse of the Soviet empire, economy, state and ideology spelled the end of the bipolar system of international relations. Throughout the 1990s and the 2000s, the U.S. sought to replace this world order with the idea of ??a U.S.-led unipolar world. Previous

It should be noted that the end of the Cold War led to the establishment of the global security system: major agreements were concluded to ensure control over nuclear and conventional weapons, and to guarantee non-proliferation and liquidation of weapons of mass destruction. The UN began to play a greater role in peacekeeping operations (of 49 such operations conducted by the UN before 2000, 36 were carried out in the 1990s). For over two decades after the Cold War, the number of international conflicts and their devastating effect decreased significantly in comparison with any of the 20-year periods during the Cold War.

Russia, China and other former socialist countries, despite differences in their political systems, were integrated into one global financial and economic system and common global institutions, even though they did not have much influence on them. Only a few countries remained outside this system, such as North Korea, Cuba and Somalia. The crisis of 2008 demonstrated financial and economic interdependence of the world. Having started in the United States, it quickly swept other countries and hit hard the Russian economy, too, thus dashing Moscow’s hopes that it would remain, as before, an “island of stability.”

Several attempts were made to legally formalize the new balance of power: by concluding a treaty on the reunification of Germany between West and East Germany, the Soviet Union, the United States, Great Britain, and France in 1990; by reorganizing the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe into the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe in 1995; by adopting the Paris Charter (1990) and the NATO-Russia Founding Act (1997), which followed up on the Helsinki Final Act; and by conducting active discussions of UN reform. In addition, the Adapted Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty was signed in 1999, and negotiations were held on joint development of missile defense systems.

However, these attempts were largely ineffective or were not completed, just as was the construction of the international security system, above all, because of U.S. global ambitions. In the early 1990s, the U.S. had a unique historical chance to lead the creation of a new, multilateral world order together with other centers of power. However, it unwisely lost this chance. The U.S. suddenly saw itself as “the only superpower in the world.” Gripped by euphoria, it began to substitute international law with the law of force, legitimate decisions of the UN Security Council with directives of the U.S. National Security Council, and OSCE prerogatives with NATO actions.

This policy laid time bombs under the new world order: NATO’s eastward enlargement; the forceful partitioning of Yugoslavia and Serbia; the illegal invasion of Iraq; and disregard for the UN, the OSCE, and arms control issues (the U.S. withdrawal from the ABM Treaty in 2002, and non-ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1996). The U.S. treated Russia as if it were a loser country, although it was Russia that put an end to the Soviet empire and the Cold War.

The first two decades after the end of bipolarity have convincingly shown that a unipolar world brings no stability or security. Monopoly both at national and international levels inevitably leads to legal nihilism, arbitrary use of force, stagnation and, ultimately, defeat.

China, Russia, new interstate organizations (the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS), regional states (Iran, Pakistan, Venezuela, and Bolivia), and even some of Washington’s allies (Germany, France and Spain) began to show growing opposition to the “American order.” Apart from building up its military potential and competing in global arms trade, Russia started to openly oppose the U.S. in some military-technical areas (for example, means to pierce missile defense systems). In August 2008, for the first time in years, Moscow used military force abroad—in the South Caucasus.

The word “imperialism” has lost its negative connotation in the Russian public discourse and is now increasingly often given a heroic resonance. Nuclear weapons and the nuclear deterrence concept have acquired an exceptionally positive meaning, while the idea of reducing nuclear weapons is now frowned upon. What “world imperialism” was formerly blamed for—the policy of building up weapons, muscle-flexing, the establishment of military bases abroad, and rivalry in arms trade—is now lauded in this country.

China, in turn, has begun to consistently build up and modernize its nuclear and conventional weapons and launched programs for developing armaments capable of overcoming the U.S. missile defense and those that can compete with U.S. precision-guided conventional systems. China has challenged neighboring countries and U.S. military domination in seas west and south of its shores and claimed access to natural resources in Asia and Africa and to control sea lanes used to transport these resources in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

The unipolar “order” was deeply undermined by Washington’s actual defeat in the Iraqi and Afghan wars and by the global financial and economic crisis of 2008. It ended with an increasingly intensive military-political rivalry between the U.S. and China in the Asia-Pacific region and the tough confrontation between the U.S. and Russia over the Ukrainian crisis.

THE UKRAINIAN MOMENT OF TRUTH

In terms of Realpolitik, with all the drama of the humanitarian aspect of the crisis and violence in southeastern Ukraine, the essence of what is happening there is simple: the United States and the European Union are drawing Ukraine into their realm, while Russia is not letting it go, seeking to keep Ukraine (or at least part of it) in its orbit of influence. However, Realpolitik does not give the complete picture of the events, as it does not take into account the social, economic and political dimensions of these developments.

The majority of Ukrainians advocate democratic reforms and integration with the West, seeing it as a way to overcome years-long social and economic stagnation, poverty and corruption, and to replace the inefficient system of government. A significant minority (10 to 15 percent) of Ukraine’s population, who live in the southeast, are opposed to pro-Western policies and favor the preservation of traditional ties with Russia. President Victor Yanukovich’s decisions first to sign an Association Agreement with the EU and then go back on his plans sharply aggravated the political division of the country: it triggered pro-European protests (“Euromaidan”) and the use of force by police, overthrow of the legitimate authorities, separation of Crimea, and a civil war in the southeast. Washington is now unfoundedly accusing Moscow of all the troubles, but Russia is only indirectly related to the internationalization of the crisis that had developed before the Crimean events.

In 2012-2013, the new ruling class in Russia regarded mass protests in the country as a Western-inspired attempt to organize a color revolution. Apparently, the Kremlin came to the conclusion that further rapprochement with the U.S. and the EU was dangerous. It therefore abandoned the policy of “European choice for Russia,” which was officially proclaimed in the 1990s and during the first period of Putin’s rule, starting from the Russia-EU summit in St. Petersburg in May 2003 and until 2007, and replaced it with the doctrine of “Eurasianism.”

On the international scene, this doctrine provides for Russia’s integration in the Customs and Eurasian Unions with other post-Soviet countries, above all, with Belarus and Kazakhstan, as well as others that would wish to join in. instead of seeking Western investments and advanced technologies (as was provided for by President Dmitry Medvedev’s “Partnership for Modernization” concept), the Kremlin launched a policy of re-industrialization of the economy, with emphasis on the defense industry, giving it 23 trillion rubles in budget allocations for the period until 2020. This U-turn has been accompanied by a propaganda campaign, unprecedented since the Cold War times, about a military threat from the West.

Against the background of this change in the Kremlin’s policy priorities, Kiev’s intention to sign an Association Agreement with the EU was perceived by Russia as a great threat to its “Eurasian” interests. Formerly, plans by Ukrainian presidents Leonid Kravchuk, Leonid Kuchma and Victor Yushchenko to apply for membership in NATO and the European Union had not caused such strong reactions from Russia.

The conservation of the state system that has been established in Russia over the last twenty years and the repudiation of major economic and political reforms have been given a doctrinal justification in the concept of conservatism urging a return to traditional moral values ??and state-political canons. Whatever the Kremlin’s attitude to this concept, legions of activists in the political class and the media openly call for the revival of great-power Orthodox Russia (some are even not slack of using elements of the Stalinist past). Appeals have been even voiced for incorporation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and occupation, after Crimea, of regions populated by ethnic Russians—south and southeast Ukraine (Novorossiya), Transdniestria, and, as occasion offers, northern Kazakhstan and parts of the Baltic States (leading ideologist of this concept Alexander Prokhanov has called this project an “empire of chunks”).

Washington and its NATO allies (except Poland and the Baltic States) for several years did not react to the new trends in Russian politics. However, after the incorporation of Crimea into Russia and the beginning of war in south-eastern Ukraine, their reaction became extremely harsh, especially on the part of President Barack Obama who previously had been accused by the conservative opposition of excessive liberalism and softness towards Moscow. The July tragedy with the Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, though its causes are still unknown, has stiffened the crisis to an unprecedented global scale.

For all the complexity of the situation, solutions are simple, and they will be sought not only in negotiations between Kiev and the southeast’s representatives, but also in Moscow, Brussels and Washington. Either the West and Russia agree on a mutually acceptable future status of Ukraine and the nature of its relations with the EU and Russia, with its present territorial integrity preserved, or the country will be torn apart, with grave social and political consequences for Europe and the whole world.

WHAT NEXT?

The failed unipolar world is being replaced with a polycentric world order based on several major centers of power. However, in contrast to the Concert of Nations (Holy Alliance) of the 19th century, the present centers of power are not equal in might and have different social systems, which are not stable yet in many respects. Although the United States’ role is declining, it still remains the leading global center of power economically (about 20 percent of world GDP), politically and militarily. China, which generates 13 percent of world GDP, is catching up with the U.S. on all counts. The European Union (19 percent of world GDP) and Japan (6 percent) can play leading roles in economy, but politically and militarily they depend on the United States and are integrated in U.S.-led alliances along with some regional countries (Turkey, Israel, South Korea, and Australia).

Russia is building its own center of power together with some post-Soviet countries. However, while enjoying global nuclear and political status and strengthening regional general-purpose forces, it still does not meet financial and economic standards of a world center of power due to its relatively modest GDP (3 percent of world GDP) and, even more importantly, due to its economy and foreign trade underpinned by the export of natural resources.

India is a leading regional center of power (5 percent of world GDP), along with some other countries (Brazil, South Africa, ASEAN countries and, potentially in the future, Iran). But there is no military-political alliance among Russia, China, India, and Brazil, and there are no signs it may be established in the future. Individually, these countries are noticeably inferior to the established military-political and the emerging economic alliance among the U.S., the EU, Japan, and South Korea.

In the last decade, the polycentric world has again begun to be divided into opposing groups of countries. One line of division lies between Russia and NATO/EU over the latter’s eastward enlargement and the European missile defense program, and was further deepened by the events in Ukraine. Another line of tensions runs between China and the U.S. and its Asian allies as they seek military and political domination in the western part of the Asia-Pacific region, control over natural resources and their transportation routes, and influence in financial and economic decision-making.

Objectively, the logic of a polycentric world pushes Russia and China towards closer partnership, and prompts the CIS/CSTO/SCO/BRICS to create economic and political counterweights to the West (U.S./NATO/Israel/Japan, South Korea/Australia). However, these trends are unlikely to evolve into a new bipolarity comparable to that in the Cold War era. Economic ties between major members of the SCO/BRICS and the West are much broader than among themselves, and they are highly dependent on its investments and advanced technologies. (For example, the volume of trade between Russia and China is only one-fifth of EU-Russia trade and one-tenth of China’s trade with the U.S., the EU and Japan). Inside the CIS/CSTO/SCO/BRICS, there are more profound differences (Russia–Ukraine, China–India, Armenia–Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan–Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan–Uzbekistan) than between members of these associations and the West. Also, there are many differences between the U.S. and European countries on many economic and political issues, especially regarding relations with Russia.

The Ukrainian crisis has not yet resolved the contradiction between tendencies towards polycentricity and new bipolarity. Rather, it exposed the nature of the emerging asymmetrical and elusive polycentricity. During the UN vote on the Crimean referendum in March Russia was unequivocally supported by ten countries, while the U.S., by 99 countries (including all NATO and EU members). But eighty-two countries (40 percent of UN members) chose not to take either side in order to keep their relations with Washington and Moscow intact. None of the SCO/BRICS countries supported Russia, and only two members of the CIS and the CSTO—Belarus and Armenia—clearly supported Moscow. But shortly after that, the Belarusian president went to Kiev and called for a return of Crimea to Ukraine in the indefinite future. Georgia, which had quit the CIS, three CIS countries, opposed Russia (Azerbaijan, Moldova and Ukraine), and even its traditional partners such as Serbia, Iran, Mongolia, and Vietnam offered no backing. However, there is no unity among the U.S. allies either. Israel, Pakistan, Iraq, Paraguay, and Uruguay declined to side with Washington. Still greater discord can be seen in NATO and the EU over sanctions and the new policy of containing Russia.

Importantly, all these countries and groups are integrated into one global financial and economic system. On the one hand, this enabled the West to impose economic sanctions on Russia, with quite tangible effects in the long term. On the other hand, for the same reason harsher, sectoral, sanctions may boomerang against their initiators and have not been unanimously supported by U.S. allies and U.S. businesses. Russia’s countermeasures against food imports from the West have affected their economies, but they can hit Russian consumers even harder, despite promises to find new suppliers and increase domestic food production (the Soviet Union could not do that over 70 years of its existence, and Russia has similarly failed over the next quarter of a century).

Generally, a common economic basis, unlike in the Cold War years, must serve as a powerful stabilizing factor for political fluctuations. However, recent experience has demonstrated an enormous opposite impact of politics: the aggravation of relations between Russia and the West is ruining their economic cooperation and the global security system.

If Ukraine is torn apart and if a new line of confrontation emerges between Russia and the West along some internal Ukrainian border, many elements of Cold War relations will be re-established between them for a long time. Renowned U.S. political scientist Robert Legvold writes: “Although this new Cold War will be fundamentally different from the original, it will still be immensely damaging. Unlike the original, the new one won’t encompass the entire global system. The world is no longer bipolar, and significant regions and key players, such as China and India, will avoid being drawn in. […] Yet the new Cold War will affect nearly every important dimension of the international system.” (Managing the New Cold War. Foreign Affairs, July/August 2014) Among areas where cooperation between Russia and the West will be stopped, Legvold names negotiations to resolve differences over the European component of the U.S. missile program; the development of energy resources in the Arctic; reforms of the UN, the International Monetary Fund, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe; and the settlement of local conflicts in the post-Soviet region and beyond. One can also add to this list cooperation in combating international terrorism and drug-trafficking, and countering Islamic extremism—the main global and transborder threat facing both Russia and the West. The offensive of Islamic fighters in Iraq has come as a reminder of this threat.

In these circumstances, the arms race will inevitably accelerate, especially in high-tech areas such as information management systems, high-precision conventional defensive and offensive armaments, boost-glide and, possibly, fractional-orbital systems. Yet this arms race will hardly compare in scale and pace with the nuclear and conventional arms race of the Cold War times, mainly due to the limited resources available to the leading powers and alliances.

Even amid the unprecedentedly acute Ukrainian crisis, the U.S. continues to cut its defense budget and cannot make its NATO allies ramp up their military spending. Russia’s economic and technological possibilities are still more limited, and the costs of a new arms race will be relatively higher for it. These factors will inevitably lead the arms control negotiations to a deadlock, and the existing arms limitation and non-proliferation system (above all, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty of 1987, the New START Treaty of 2010 and even the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty) may collapse.

If there emerges a crisis between China and the U.S. and its allies in the Pacific, China will move closer to Russia. But Beijing is unlikely to make sacrifices for the sake of Russian interests; instead, it will seek to use Russia’s resources for rivalry with its own opponents in Asia and the Pacific (the Chinese call Russia their “resource rear,” obviously thinking this flatters Moscow). At the same time, China will hardly want to exacerbate relations with the U.S.—tensions between Russia and West place Beijing in the most advantageous position in a polycentric world. Paradoxically, China has become a factor that balances relations between the West and the East (represented by Russia), a position Moscow has always sought to take.

Russian foreign-policy makers and diplomats for twenty years advocated the concept of polycentric world as an alternative to American unipolarity. But in reality Moscow appeared to be unprepared for such a system of relations as it has not yet grasped its basic rule, which was well known to Russian chancellors of the 19th century—Karl Nesselrode and Alexander Gorchakov. The rule is: one should make compromises on individual issues in order to have closer relations with other centers of power than they have among themselves. Then one can receive concessions from all and everyone, gaining from the sum-total of interests realized.

Meanwhile, Russia’s current relations with the U.S. and the EU are worse than relations between them and China, let alone between themselves. This factor may pose big problems for Moscow in the foreseeable future. The wedge driven between Moscow and Washington (and its allies in Europe and in the Asia-Pacific region) will be taking its toll on Russia for years. The giant of China is hanging over Siberia and the Russian Far East, but one can make friends with China only on its own terms. Unstable countries threatened by Islamic extremism adjoin Russia’s south. In the European part, Russia is bordered by not very friendly countries such as Azerbaijan, Georgia, Ukraine, the Baltic States and not very predictable partners such as Belarus. Certainly, Russia is facing no risk of international isolation or military aggression, despite the new U.S. policy of containment. But nor did the Soviet Union face such risks. Besides, it was much larger, stronger economically and militarily, had secured borders, and did not depend so heavily on world oil and gas prices. Yet how the Soviet Union ended up in 1991 is well known.

If Russia and the West reach a compromise on the future of Ukraine, acceptable to both Kiev and the southeast of the country, it will take some time before cooperation resumes, but gradually the confrontation will be overcome and the formation of a polycentric world will begin. It can serve as the basis for a new, more balanced and stable world order, albeit much more complex and volatile. It must address problems of the 21st century, rather than return to politics of the past century and earlier times such as overthrowing undesirable regimes, imposing one’s values and customs on other nations, entering into geopolitical rivalry, and redrawing national borders by force to remedy historical injustices.

Only such new basis will make it possible to significantly enhance the role and efficiency of international norms, organizations and supranational institutions. The fundamental commonness of interests in a multipolar world warrant greater solidarity and restraint in choosing instruments for pursing one’s interests than the fear of a nuclear catastrophe did in the last century. This is required by new security challenges—the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and the growth of Islamic extremism and international terrorism. Among other factors are the mounting climatic and environmental problems; shortages of energy resources, fresh water and foodstuffs; the population explosion; uncontrollable migration; and the threat of global epidemics.

The policies of the European Union, India and Japan are predictable within a narrow range of options. The decisive role in shaping the future world order will be played by the policy course to be adopted by the United States, China and Russia. Without falling into neo-isolationism, the U.S. will have to adapt to the realities of a polycentric and interdependent world in which arbitrary use of force will be tantamount to throwing stones in a glass house. As the most powerful member of such a world order, America can play a very important role, acting within the framework of international law and legitimate institutions. But any attempts at hegemony and the rule of force will meet with sabotage on the part of U.S. allies and resistance from other global and regional powers.

China should avoid the temptation to build up weapons stockpiles and conduct a forcible policy to meet its growing resource requirements. Otherwise, neighboring countries in the west, south and east will unite against it under U.S. leadership. China’s fast-growing economic power should boost its global economic and political influence accordingly, but this must be done peacefully by mutual agreement with other countries.

As for Russia, it can become a full-fledged global center of power only if it moves from a resource-based to a high-tech economy. This implies taking vigorous efforts to break the looming political and economic stagnation threatening to plunge the country into a steep decline. But this can be achieved only if Russia abandons the great-power rhetoric and narcissism regarding metaphysical spiritual traditions, autarky, and the hopes of making the defense industry a locomotive of economic growth (as the USSR had been doing until it collapsed). All this may temporarily rekindle patriotic feelings in society, but will most likely exacerbate Russia’s problems. Real economic progress will require, above all, democratic political and institutional reforms: genuine separation and regular change of powers, fair elections, disengagement of government officials and lawmakers from business, an active civil society, independent media, and much more. There is no other way for large investments and high technologies to come to Russia—they will not be generated by internal sources, and they will not come from the West or China which itself gets these assets from countries with innovation-based economies.

Perhaps, very few critics of the present philosophy and practices of “Eurasianism,” conservatism and national-romanticism could express the idea of ??the European alternative better and more convincingly than Vladimir Putin himself. Several years ago, he wrote: “This choice was largely predetermined by the national history of Russia. The spirit and culture of our country make it an integral part of European civilization […] Today, when we are building a sovereign democratic state, we fully share the basic values and principles that make up the outlook of most Europeans. […] We view European integration as an objective process that is an integral part of the emerging world order. […] The development of diversified ties with the EU is Russia’s fundamental choice.” (V. Putin. Fifty Years of European Integration and Russia. March 25, 2007)

According to this ideology, which must serve as the foundation of public life and mentality, Russia is to return to the European path of development, which should not be confused with trade flows and pipeline routes. The European path primarily implies the transformation of Russia’s economic and political system in accordance with basic European norms and institutions, while taking into account Russian needs and peculiarities of the current phase of its historical development.