For citation, please use:

Arapova, E.Ya. and Balakhonova, S.I., 2023. Foreign Companies’ Behavior in the Russian Market under Sanctions: Speculation and Reality. Russia in Global Affairs, 21(4), pp. 47-64. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2023-21-4-47-64

The start of Russia’s special military operation (SMO) in Ukraine in February 2022 and the ensuing unprecedented sanctions against Russia entailed a series of corporate boycotts by restrictive jurisdictions.

Faced with the threat of sanctions, companies seek to protect themselves from the risk of unintended violation, which prompts them to “overcomply” with the sanctions, subjecting their counterparties to rigorous due diligence checks, distancing themselves from them as much as possible, and limiting their operations more than required by the regulatory authorities. Companies also use this strategy to hedge risks from restrictive measures that might be rapidly introduced by regulators if geopolitical contradictions deepen.

Another reason for overcompliance is that regulators determine the scope of sanctions too vaguely, thus forcing companies to stop interaction with the target country. Sweeping sectoral restrictions and export control measures against Russia, sanctions against members of the political elite and state-owned company executives, disconnection of large banks from SWIFT, the constant expansion of the list of persons subject to blocking sanctions, and the spread of “hybrid sanctions,” when sectoral sanctions can provide grounds for including an individual or entity in the blocking lists, can also cause foreign businesses to be overly cautious.

The scale of corporate boycotts and their sectoral and geographical patterns directly determine the severity of sanctions against the Russian economy. The negative impact of sanctions has been extremely politicized lately and become the subject of multiple speculations. This is why the present study aims to properly assess the consequences of foreign companies’ pullout from Russia and the possibility of replacing them. Since Russia has been forced to act in a new political reality since 2022, it is now extremely important to identify the patterns that underlie foreign companies’ choice of behavioral strategies and to study the behavior of companies from non-restrictive jurisdictions in order to find out the level of their sanctions compliance.

It is important to try, firstly, to determine the real scale of foreign companies’ withdrawal from the Russian market; secondly, to assess the degree of sanctions compliance by foreign businesses, the balance between existing political and reputational risks (risk of secondary sanctions and reputational costs for companies that continue to work with Russia, in the context of current informational pressure), on the one hand, and the economic expediency of leaving the Russian market, on the other; and thirdly, to identify the key factors (business characteristics) that determine behavioral strategies with regard to Russia after the start of the SMO.

The study raises a number of questions: What is the real dynamics of foreign companies’ withdrawal from the Russian market? What is the geographical and sectoral affiliation of companies that have left Russia, or suspended operations, or continue to work without scaling back their business activities? What sectors of the Russian economy are foreign companies less eager to leave? What are the differences in the behavior of companies from non-restrictive jurisdictions and countries that have initiated anti-Russian sanctions, and what factors determine their behavior? To what extent does the behavior of foreign companies depend on the form of ownership and the share of the Russian segment in their revenue structure?

Discourse Analysis

This study develops the nominalist traditions established by the “classics” of global sanctions research. The works of Gary Hafbauer (Hufbauer et al., 2009), Francesco Giumelli (Giumelli, 2013), Thomas Morgan and co-authors (Morgan et al., 2014), Gabriel Felbermayr (Felbermayr et al., 2020), and others use information from large sanctions databases. However, databases compiled in the “classical” manner exhibit aggregated restrictive measures and do not fully reflect the current state of global sanctions regime in general, and the nature of pressure on Russia in particular. The U.S. President’s Executive Order #14024 of April 14, 2021 (Executive Order, 2021) basically created a new regime of sanctions against Russia, when one regulatory document implies numerous actions. The U.S. executive authorities expand the lists of individuals under sanctions, issue waivers for certain transactions or areas, carry out administrative or criminal prosecution of violators of sanctions, and sometimes exclude certain individuals from the sanctions lists. So, a broader use of “targeted restrictions” against individuals and organizations, rather than whole countries, requires a more delicate adjustment of the sanctions toolkit” (Timofeev, 2023).

The new reality increasingly necessitates more detailed databases of sanctions that record all restrictive measures, or databases of individuals and/or legal entities subject to such measures. In Russia, a paradigm shift has led to the creation of a database of sanctions by the Russian International Affairs Council, which served as the basis for a series of analytical works (Timofeev, 2020, 2021 a, b, 2022), as well as of the X-Compliance database by the Interfax Group, which identifies sanctioned persons and related assets. However, existing large databases focus mostly on sanctions tools or objects of sanctions, while the databases of government or corporate reaction to sanctions are quite limited.

As for Russia, the main source of information on the behavior of foreign companies is the Yale School of Management Database (YSM), which classifies legal entities operating in Russia by strategy, their jurisdiction, and industry. It is these assessments that currently dominate Western discourse and underlie research studying the economic effects of sanctions against Russia.

These data have been analyzed by Alison Lawlor Russell (Merrimack College in North Andover, U.S.) (Russell, 2023), Jeffrey Sonnenfeld (Yale School of Management, U.S.) (Sonnenfeld et al., 2022), and Simon Evenett (University of St. Gallen, Switzerland) and Niccolò Pisani (International Institute for Management Development, Switzerland) (Evenett and Pisani, 2022). Experts study the behavior of foreign companies as entities capable of influencing the policies of states; determine the damage caused to the Russian economy by the withdrawal of companies from the Russian market; and also assess the number, capitalization, and industry profile of companies that have actually left Russia.

Alison Lawlor Russell (2023) hypothesizes that the ability of multinational corporations to influence the behavior of states during a conflict increases if a company holds a monopoly position in a vital sector of the economy of the target country, although this theory is not supported by the Russia sanctions case, which shows that sanctions have no influence on the political course of the target country.

Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and his colleagues (Sonnenfeld et al., 2022) conclude that Russia has lost companies representing about 40% of its GDP, reversing nearly all of three decades’ worth of foreign investment and buttressing unprecedented simultaneous capital and population flight in a mass exodus of Russia’s economic base. The researchers note the aerospace industry as being particularly sensitive to such changes. At the same time, Simon Evenett and Niccolò Pisani (2022) concluded that as of the end of November 2022 only 8.5% of EU and G7 companies had divested at least one of their Russian subsidiaries. They found out that there had been more confirmed exits by foreign firms headquartered in the United States than those based in the EU and Japan. However, fewer than 18% of U.S. subsidiaries have actually divested. The experts also claim that EU and Japanese firms that have exited to date tend to have very low levels of profitability, and there are fewer confirmed exits by EU and G7 firms in the agricultural and resource extraction sectors than in manufacturing and services sectors.

Such contradictory estimates of the scale of corporate boycotts and their impact on the Russian economy, based essentially on the same statistical resources, can be explained by, firstly, the politicization of studies by individual authors, and secondly, the lack of data and company characteristics contained in the database. These limitations leave room for speculative interpretations of results. In response to this empirical gap, the authors of this study propose their own database of foreign companies, which, firstly, will make it possible to conduct a more objective analysis of real trends in the behavior of foreign companies in Russia and compare it with the YSM data, and secondly, will significantly expand the set of company characteristics needed to answer practical questions and test a number of conceptual hypotheses.

Research Methodology

When building the database of foreign companies, experts of the Center for Sanctions Policy Expertise of MGIMO’s Institute for International Studies focused on five strategies proposed by the Yale School of Management for the behavior of foreign companies in the context of anti-Russian sanctions. These are “cooperation as before” (a company continues to operate as usual), “delaying new forms of cooperation while continuing contracted operations” (a company is postponing planned investments, while continuing substantive business), “reduction of operations” (a company is scaling back some significant business operations but continuing some others), “suspension of activities without leaving the market” (a company is temporarily curtailing most or nearly all operations while keeping return options open), and “leaving the market” (a company is totally halting Russian engagements or completely exiting Russia).

However, foreign companies’ behavior strategies identified in our database do not duplicate the American database as they have been analyzed through confirmed factual information about continued activities or withdrawals from Russia by releasing relevant official statements, information about the sale of the business and its new owners, etc. The greatest difficulty lies in assessing the behavior of companies that have refrained from any official statements, have not been active on the corporate websites and social networks, while not releasing any information on the fulfillment of their obligations under previously concluded contracts or the execution of new transactions.

In this case, decisions on their behavior were made on the basis of “mirror data,” that is, an analysis of statements and other information from their previous Russian counterparties (either data on completed transactions or an assessment of prospects for resuming cooperation). In most cases, in the absence of signs of continued business activity, Russian counterparties were defined as having suspended business activities. Complete withdrawal from the market was confirmed for only nine foreign companies in this group.

For the purposes of this study, the database has been supplemented with new parameters, with each company having several characteristics:

- country of origin;

- a sign of the friendliness of the country of origin;[1]

- behavior strategy;

- information about the new owner (if retreated from the market):

(1) transaction date (2) new owner (3) new owner’s country;

- industry affiliation;

- form of ownership;

- capitalization level;

- Russian market share in revenue structure;

- affiliation (assets in) with the countries initiating anti-Russian sanctions.[2]

As of March 2023, the database featured 1,539 companies, including 1,414 legal entities from restrictive jurisdictions and 125 individuals from non-restrictive jurisdictions. To achieve one of the goals of the study and assess, among other things, the real scale of foreign companies’ withdrawal from Russia in comparison with the Yale School of Management Database, the core of the authors’ database is made up of the companies contained in the American dataset. To study the industry profile of companies, the following major sectors of the economy were identified: resource extraction and processing; energy; industry (aviation and automotive industry, instrument manufacturing, chemical industry), IT and microelectronics; financial sector; agriculture and food; trade; health and pharmaceutics; business services; communication services; consumer goods; construction; tourism; and others.

The study also reflects the capitalization of companies measured in billions of U.S. dollars. To achieve the most comparable results, the time gap in data for the entire set of companies was no more than three days. The current analysis uses data effective as of the beginning of March 2023. The share of the Russian segment in the companies’ revenues is expressed in percentage points according to the ORBIS database as of the end of 2022 (ORBIS, 2022).

Dynamics and Scale of Foreign Companies Withdrawal

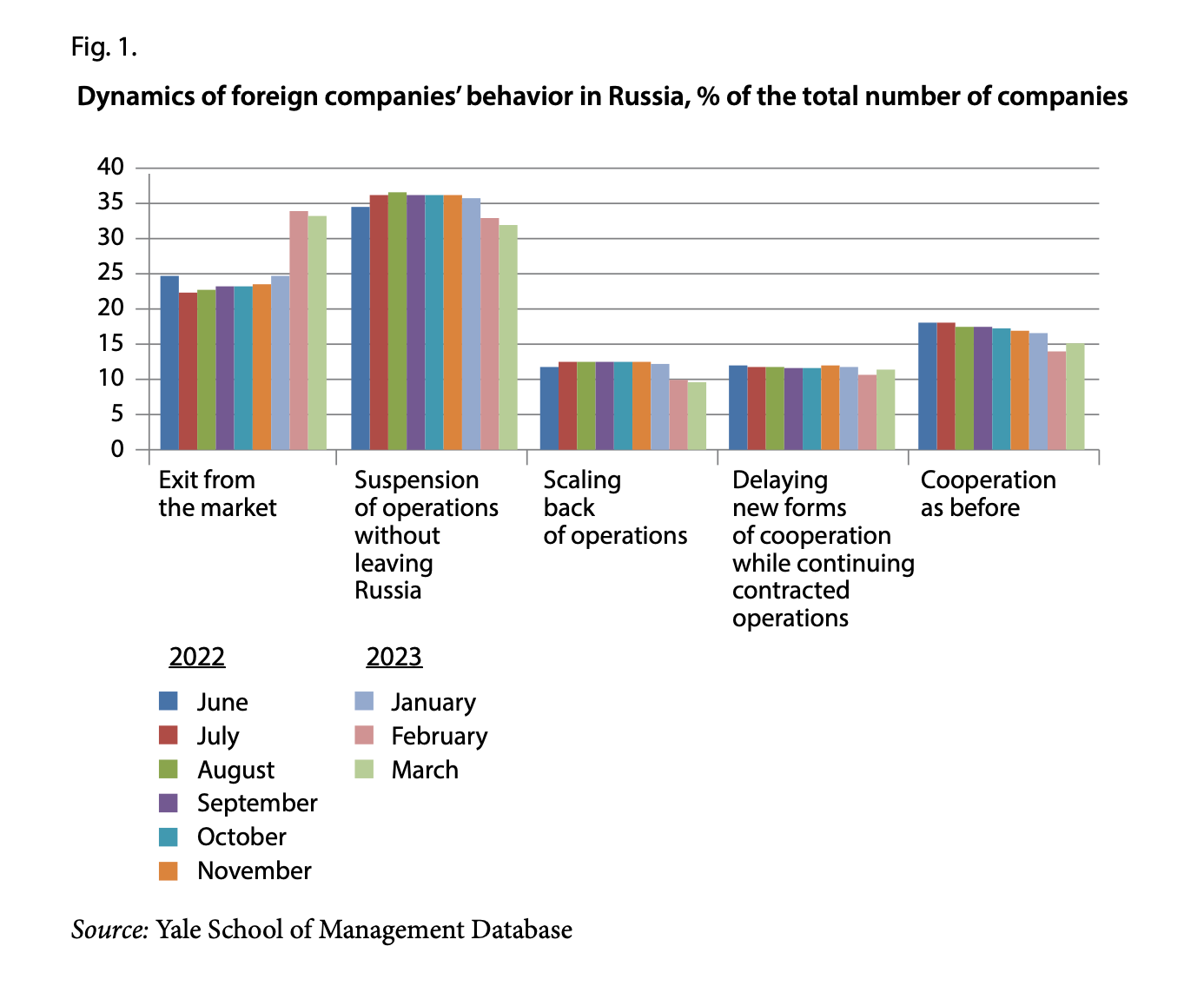

The analysis of the American Yale School of Management Database allows us to determine three stages in the behavior of foreign companies (see Fig. 1). In the period from March to June 2022, there was a sharp increase in the number of companies that had announced their exit from the Russian market or suspended their activities in Russia. According to the American data as of June 2022, the most preferred strategy was “suspension of activities without leaving the market” (468).

Since July 2022, a number of foreign companies have changed their strategies from “leaving the market” (303 in July compared to 332 in June) to “suspending activities without leaving the market” (an increase from 468 to 496 companies). The delay was partly due to the desire to preserve opportunities for further work in Russia and due to the expectation of changes on the SMO fronts and in the global geopolitical situation, but partly due to the search for new owners and the development of plans to sell assets in Russia, including application for permission from the Government Commission for Monitoring Foreign Investment in the Russian Federation.

From November 2022 to February 2023, there was an increase in the number of companies leaving the market, which is largely due to the fact that the waiting companies had received the necessary permits and were about to make their deals. Another sharp increase in the number of companies leaving the Russian market (from 341 to 515) was recorded from January 2023 to February 2023. At the same time, more companies had stopped operating as before (their number grew from 210 to 226) and fewer scaled back their operations while continuing to work in Russia (a decrease from 168 to 149).

As a result, according to the American data, as of the end of March 2023, 520 foreign companies completely left the Russian market, 502 companies suspended activities in Russia, 148 companies reduced operations, 177 companies announced the postponement of new projects but continued to honor current contracts, and 234 companies kept operating as before (or even stepped up their activities).

However, the objectivity of the American data can be questioned for two reasons.

Firstly, after a double check, some companies’ plans to exit the market were not confirmed. Of the 520 companies that the American database marked as “left the market” as of March 2023, only 420 were confirmed by official statements. In addition, the American database does not distinguish between companies that have left the Russian market and companies whose business has been sold to the local management or strategic investors, when, in fact, the companies actually leave but their business remains.

This factor is one of the main reasons why the damage caused to the Russian economy by the sanctions is “overestimated,” for example, by J. A. Sonnenfeld and his colleagues (Sonnenfeld et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the study confirmed the sale of companies to new owners in 114 cases. In 95% of cases the buyers are Russian legal entities, and the rest were acquired by Turkish, Chinese, Kazakh, Lebanese, and UAE companies. For example, the Turkish home appliances market leader Arcelik acquired the Russian business of American Whirlpool and the Indesit plant in Lipetsk; the Polish group Cersanit SA sold its Russian assets, including the Syzran Ceramics Plant, to Sangre International LTD, a company registered in the UAE. The Russian business of the Polish retailer LPP was sold to Chinese FES (Far East Services) Retail.

Some of the companies that had previously announced their exit returned to the Russian market, which was not reflected in the American database due to politically biased inertia (such as the Swedish logistics company Postnord, which resumed mail delivery to Russia in November 2022). Often, sold businesses reappear in the Russian market under new names. For example, the products of Spanish Inditex, which sold the business to the Lebanese group Daher, or American Reebok, whose Russian operations were acquired by the Turkish company FLO Retailing, continue to be supplied to the Russian market under new brand names.

As mentioned earlier, 55 companies are in the “gray zone”: in the absence of any official statements regarding the strategy of further work with Russia or reports on the sale of assets (as well as information about any activity since the start of the SMO), the American database marks them as “left the market.” At the same time, indirect signs indicate that only nine of them can be said to have exited the Russian market completely, while the rest have suspended their operations without actually leaving the market.

Secondly, the announcement by companies of their “withdrawal” due to political “solidarity” with the official policy of their home countries and the fear of secondary sanctions and reputational losses does not always mean the actual halt of operations with Russia. The statistics of companies’ statements regarding their behavioral strategy over time appears to be quite indicative: about 65% of companies that announced their exit from the market and about 90% that announced the suspension of activities in Russia did so in February-April 2022. The peak of such statements was expectedly recorded in March 2022 when Russia was hit by a tsunami of sanctions.

According to the MGIMO database, by April 2023, the statistics of corporate behavior looked as follows: cooperating as before—249 companies; delaying new forms of cooperation while continuing contracted operations—156; reducing operations—186; suspending activities without leaving the market—519, and leaving the market—429 companies. Data verification showed that 12 companies listed in the American database as having left the Russian market continued to work with Russia. Another 32 companies have officially announced the suspension of activities but are considering resuming cooperation, although the American database names them in advance as having left the Russian market.

These statistics clearly illustrate the declining maximum effectiveness of sanctions, indicating that the peak of pressure and its negative impact on Russia has been passed. Everyone who wanted to leave the Russian market has already left, and those remaining have made a firm and balanced decision. We can still expect certain adjustments between the “leaving the market” and “suspending operations without leaving” groups, but this is unlikely to radically change the picture. Companies seek to maintain their presence in Russia and adapt to the new conditions being guided primarily by commercial considerations. In general, the exit of foreign companies from Russia was largely motivated by pressure from the key initiating countries. The waiting position of a significant number of companies that remain in Russia to date actually duplicates the behavior of states that are gradually adapting to the imposed restrictions (Nephew, 2018).

Analysis of Foreign Companies’ Behavior With Account of Their Characteristics

To better analyze and quantify the scale of corporate boycotts, it is important to take into account not only the total number of companies leaving Russia or maintaining a presence, but also the size of these companies.

Among all companies from unfriendly countries, it is relatively small companies that continue their operations in Russia as before since they are less involved in global added value chains and, as a result, less exposed to sanctions risks (the average capitalization of such companies is $25.2 billion). Yet the analysis also shows that large international companies are in no hurry to leave the Russian market: while scaling back their operations in Russia, they are trying to adapt to the new conditions and maintain their presence in the Russian market.

This applies to both Western companies and legal entities from jurisdictions that do not support sanctions against Russia. The average capitalization of companies from unfriendly jurisdictions that have suspended operations without leaving the Russian market is estimated at $52.9 billion, the capitalization of companies that have delayed new forms of cooperation while continuing contracted operations averages at $59.7 billion, and that of companies reducing operations, but continuing to work in Russia is $74.8 billion. The average capitalization of foreign companies that have left the Russian market has amounted to $33.2 billion for countries and $30.3 billion for companies from unfriendly jurisdictions.

So, although in numerical terms partners from non-restrictive jurisdictions cannot be considered a symmetrical alternative to the outgoing Western brands, in terms of the size of the remaining companies the imbalances in presence may be considerably smaller.

As expected, companies from non-restrictive jurisdictions are much more eager to keep their business in Russia. The share of companies that are either continuing to operate as before or have increased their presence in Russia due to vacated niches has amounted to 66.1% against 11.7% for companies from unfriendly countries. At the same time, the share of companies that have announced their complete withdrawal from the Russian market is just 8.2% against 31.6%, respectively.

It is important that the form of ownership really matters and determines the strategy of companies’ behavior (Table 1). State-owned companies expectedly act relatively more in line with the official policy:

- a larger percentage of state-owned (or state-affiliated) companies from unfriendly countries have left the Russian market, a smaller percentage has stayed (as compared to private companies);

- no state-owned company from countries that do not support anti-Russian sanctions has officially left the Russian market, while private companies are more cautious and show a higher level of sanctions compliance.

This circumstance may help increase (or preserve) the number of foreign counterparties in the current situation since the degree of government involvement in developing countries that have not joined the anti-Russian sanctions is relatively higher, while the market in unfriendly countries is dominated by private companies which are guided more by considerations of commercial gains than the official government policy.

Sectoral Trends in Corporate Behavior

The list of the top five industries whose companies have left the Russian market looks as follows: business services (96), industry (87), IT and microelectronics (65), financial sector (31), and trade (25). A comparison of the sectoral behavior patterns for companies from “unfriendly” jurisdictions and other countries reveals the possibility of replacing the outgoing unfriendly companies with partners from countries that have not joined the sanctions (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

Following export control measures taken by Western countries and the subsequent retreat of IT companies, retail chains, and agents that provided various types of business services (legal, engineering, consulting, etc.), their place is being taken by companies from non-restrictive jurisdictions. This is particularly noticeable in trade, where practically all companies from non-restrictive jurisdictions have not only retained their full presence but have also been able to increase their market share by expanding the range of goods traded.

The natural resource sector (power and mining industries) has proved to be relatively more stable since the possibility of replacing companies from unfriendly countries with companies from partner states is significantly higher there.

When analyzing how the share of the Russian market impacts foreign companies’ revenues, we found out that the higher a company’s dependence on the Russian market, the higher the likelihood of its continued cooperation: companies with a higher share of the Russian market in the structure of their revenues, at 7.5-7.8% on the average, stay in Russia.

Companies with a smaller share of the Russian market in the revenue structure are more willing to declare their retreat or suspension of operations in Russia, although Western companies are much more prepared to sustain commercial losses for the sake of sanctions than businesses from partner countries: the average share of the Russian market in the revenue structure of companies from the countries that initiated anti-Russian sanctions, which have left the Russian market, is 3.9% compared to 1.3% for companies from non-restrictive jurisdictions.

* * *

Existing sources of data on the behavioral strategies of foreign companies in Russia after the start of the SMO are extremely politicized: about 25% of companies recorded in the Yale School of Management Database as having left the Russian market has not been confirmed by relevant statements or information about the sale of Russian assets to new owners. Moreover, relatively small companies are leaving the market, while large international corporations are scaling back their operations in Russia but are more likely to adapt to the new conditions and maintain a presence in the country. Accordingly, due to the difference in the level of capitalization of companies that maintain their presence in Russia and are leaving it, the negative impact on the Russian economy as a whole is not as significant as the estimates based on an analysis of the list of companies suggest.

The Russian IT sector, the business services sector, and the financial sector have expectedly been relatively more vulnerable. At the same time, the natural resources sector (power and mining industries) has turned out to be relatively more stable since the possibility of replacing companies from unfriendly countries with companies from partner countries is significantly higher there.

MGIMO’s database of foreign companies will be consistently improved and expanded. The main emphasis will be on enlarging the list of companies from jurisdictions that do not support sanctions against Russia and continue to operate or are just entering the Russian market. Therefore, the list of corporate behavior strategies will be supplemented with new categories such as “Started operations in Russia” and “Resumed operations in Russia” for companies that previously suspended activities in the Russian market. Work will continue to double-check the activity of foreign companies in Russia (including the registration status of legal entities, activity on social networks and on the corporate websites, the correctness of contact information, and statements by Russian counterparties of foreign companies). In addition, it is planned to deepen the analysis of foreign companies’ affiliation with the countries that initiated anti-Russian sanctions in order to test new hypotheses and identify factors determining the dimension of the sanctions impact on foreign businesses from both unfriendly countries and other jurisdictions.

The article was prepared with financial support from the Institute for International Studies at the Russian Foreign Ministry’s MGIMO University, Project 2025-04-06. The authors thank anonymous reviewers for their professional comments and valuable recommendations.

Evenett, S. and Pisani, N., 2022. Less than Nine Percent of Western Firms Have Divested from Russia. SSRN, 20 December. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4322502 [Accessed 17 March 2023].

Executive Order, 2021. Executive Order on Blocking Property with Respect to Specified Harmful Foreign Activities of the Government of the Russian Federation. The White House, 15 April. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/04/15/executive-order-on-blocking-property-with-respect-to-specified-harmful-foreign-activities-of-the-government-of-the-russian-federation/ [Accessed 17 March 2023].

Felbermayr, G. et al., 2020. The Global Sanctions Data Base. European Economic Review, 129. [pdf]. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342551068_The_Global_Sanctions_Data_Base [Accessed 16 August 2023].

Giumelli, F., 2013. How EU Sanctions Work: A New Narrative. Chaillot Papers by the European Union Institute for Security Studies. Condé-sur-Noireau: Corlet Imprimeur.

Hufbauer, G., Shott, J., Elliott, K. and Oegg, B., 2009. Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. Third Edition. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Morgan, T.C., Bapat, N. and Kobayashi, Y., 2014. The Threat and Imposition of Sanctions: Updating the TIES Dataset. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 31(5), pp. 541-558.

Nephew, R., 2018. The Art of Sanctions: A View from the Field. New York: Columbia University Press.

ORBIS, 2022. ORBIS: A Global Company Database. Harvard Business School. Available at: https://www.library.hbs.edu/find/databases/orbis [Accessed 17 March 2023].

Russell, A.L., 2023. Digital Blockade or Corporate Boycott?: A New Tactic of War. Journal of Strategic Airpower &Space Power, 2(1), pp. 16-30.

Sonnenfeld, J., Tian, S., Sokolowski, F., Wyrebkowski, M. and Kasprowicz, M., 2022. Business Retreats and Sanctions Are Crippling the Russian Economy. SSRN, 20 July. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4167193 [Accessed 17 March 2023].

The Government of Russia, 2022. Order No. 430-r of March 5, 2022. The Government of Russia, 7 March. [pdf]. Available at: http://static.government.ru/media/files/wj1HD7RqdPSxAmDlaisqG2zugWdz8Vc1.pdf [Accessed 7 March 2023].

Timofeev, I.N., 2020. COVID-19 i politika sanktsy: opyt ivent-analiza [COVID-19 and the Policy of Sanctions: An Event Analysis]. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo universiteta. Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, 13(4), pp. 449-464.

Timofeev, I.N., 2021a. Politika sanktsy Evropeiskogo Soyuza. Opyt sobytiynogo analiza [Approaching the EU Sanctions Policy: An Experiment with Event Analysis]. Sovremennaya Evropa, 2, pp. 17-27.

Timofeev, I.N., 2021b. Sanktsii protiv Rossii: vzglyad v 2021 g. Doklad 65/2021 [Sanctions Against Russia: A Look into 2021. Report 65/2021]. Moscow: RIAC NPMP.

Timofeev, I.N., 2022. Politika sanktsy protiv Rossii: novy etap [The Sanctions Policy Against Russia: The New Stage]. Zhurnal Novoi ekonomicheskoi assotsiatsii, 55(3), pp. 198-206.

Timofeev, I.N., 2023. Kak issledovat’ politiku sanktsy? Strategiya empiricheskogo issledovaniya [How to Study the Sanctions Policy? The Strategy of Empirical Research]. Mezhdunarodnaya analitika, 14(1), pp. 22-36.

***

[1] Division into restrictive and non-restrictive jurisdictions is based on the Russian Government’s Resolution of March 5, 2022 (see The Government of Russia, 2022).

[2] The affiliation with the countries initiating anti-Russian sanctions in this study is operationalized through the following parameters: legal registration of a company; key shareholders; location of production facilities and subsidiaries; main regions of operation.