For citation, please use:

Deriglazova, L.V., 2023. “Time Is Out of Joint”: EU and Russia in Quest of Themselves in Time. Russia in Global Affairs, 21(4), pp. 176-198. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2023-21-4-176-198

The current conflict between Russia and the Western countries, and especially the European Union, is existential. The leaders of both Russia and the EU see it as a challenge to the very foundations of their existence—Russia as a sovereign state and the European Union as an integration association of twenty-seven countries. The sides openly declare that the outcome of this conflict will determine not only their future, but also that of the entire world. However, there is no direct military clash between Russia and the EU, and most of the countries involved hope to avoid it. Otherwise, in case of a big war in Europe the conflict may shift from the sphere of disputes over the philosophy of being to that of physical survival.

This article does not discuss the military-political component of the conflict but offers a look at the ideological (paradigmatic) disagreements between the EU and Russia, which reflect one of the root causes of the conflict. Over the last thirty years we have seen almost thirty European countries changing the vector of their development. However, voluntary reversal from the Socialist model to a market economy and a democratic political system has led to different results. The period of rapprochement between Russia and the EU in the late 1990s was followed by growing estrangement, which indicated that the sides had different understandings of reform goals and strategies for achieving the set goals. It also showed how the same events in common history entailed different political courses and, at times, antipodal political choices.

Theoretically, the present study is based on the idea of a breach in the modern time regime, postulated by German scholar Aleida Assmann (Assmann, 2020). Central to Assmann’s analysis is the way modern societies look back on their history and the “disintegration and re-establishment of the relationship between the past, the present, and the future,” which Assmann defines as temporal breaches. Assmann interpreted the idea of the non-linear development of modern societies, which had been discussed by scholars before, metaphorically as hiatuses (breaches or ruptures) in time, which lead to certain turns in the development of countries and peoples. The modern time regime (modernity) was characterized by a belief in a better future, but in the last twenty years many EU countries and Russia seem to have been “obsessed with history.” They are revising their past—often their common past—in earnest (Assmann, 2016).

Many EU countries are facing what can be defined as hiatuses due to reflections (often tormenting) on the past. Among these countries are Germany, Spain, Greece, Portugal, and former Eastern Bloc countries, including former constituent republics of the Soviet Union. In the 20th century, these countries experienced radical changes in their political and economic systems. Temporal breaches can be clearly seen in the history of Russia over the last 100 years or so when the vector of the country’s development changed. The construction of socialism proceeded under the slogan of “renunciation of the old world,” while the post-Soviet transformation was tantamount to the rejection of the Soviet model of national development.

The notion of modernization was an important part of the EU-Russia cooperation narrative and of the way how Russia and the EU shaped relations with each other and defined their role in the present world and in the future. The terminology of modernization was extensively used in EU and Russian rhetoric, including in the Partnership for Modernization cooperation program of 2010-2014. While the terminology used by strategic partners was similar, their interpretation of the goals, means and results of their cooperation, their role in the changes afoot in the continent, the essence of events, and Europe’s possible future differed. These discrepancies often caused mutual annoyance and accusations of deliberate distortion of the essence of the agreements, but neither side denied the existence of ideological disagreements. Let us look at these discrepancies through the lens of the modernization theory and the temporal breach concept.

“Time, Forward!”: Modernization Theory and the Modern Time Regime

Assmann maintains that ancient cultures were characterized by a special attitude towards the past, which occupied “a privileged position and legitimized the regulatory foundations of the present and the future.” According to Assmann, modernity is characterized by reluctance to see the past as a means of legitimizing the present and by obsession with the future—better, new and unknown (Assmann, 2020). An excellent metaphor for time in modernity is the name of the Soviet movie Time, Forward! released in 1965 and its main musical theme composed by Georgy Sviridov. It is highly symbolic that this melody served as the signature tune of the main daily news program Vremya (Time) on Soviet television for more than twenty years (1968-1991). It is also worth recalling that in 1961 it was officially announced that the USSR was to build the “material basis of Communism” by 1980.

Modernization theory took shape in Western science in the 1950s-1960s as a continuation of the classical theory of social evolution, which implied the existence of a single line of development for all societies, following the Western civilizational model. According to that theory, scientific and technological progress was the main guideline for development, where the future was presented as a reliable reference point, a brilliant prospect. The 1960s are often characterized as the “golden decade” of the technological and economic boom that followed the postwar recovery of Western European society. Researchers began to criticize modernization theory in the mid-1970s, as the negative consequences of the economic growth in consumer society became clear to the naked eye. Assmann writes that the future is depleted by the development of a civilization that exploits resources in an inept manner (Assmann, 2020).

The 1980s saw the emergence of theories (critical theory, postmodernism) that postulated the need to change the Western countries’ development vector. It was also recognized that modernization in the socialist and Third World countries did not correspond to the Western models (see, for example, Hoffmann and Laird, 1985). The progressivist modernization theory was gradually replaced by theories that focused on the specifics of the transition from traditional to modern societies, the driving forces of such changes, the role of political regimes, and the specifics of the transformation of postindustrial society.

In the 20th century, sociologists, political scientists, and economists came up with convergence theory (idea about the convergence of the socialist and capitalist systems) as part of the critique of capitalist society (see, for example, Mishra, 1976; Wilensky, 2002), but the self-destruction of the socialist system made more relevant theories of a democratic transition of socialist countries and totalitarian and authoritarian regimes to new economic, political and ideological foundations (see, for example, O’Donnell et al., 1986; Linz and Stepan, 1996). In Russia, the 2000s were marked by heated debates between the proponents of postmodernist theories and advocates of democratic transition (Kapustin, 2001; Melvil et al., 2012); the development of a methodology for studying political transformations in Russia and other countries (Melvil et al., 2012); and the discussion of the results of transformations (Lukyanov and Soloviev, 2019). At the beginning of the 21st century, Ronald Inglehart’s ideas about democracy and the values of independence and self-realization of the individual play an important role in the revision of modernization theory as a new understanding of the purpose and means of modernization, with the individual at the very center (Inglehart and Welzel, 2011).

Igor Poberezhnikov (2011) identified various meanings of modernization: transition from traditionality to modernity (from the Middle Ages to Modern and Contemporary Times); catch-up development, including catch-up development of Third World countries; transformation of post-socialist countries; and reform of modern societies in response to new development challenges. Later, advancing the value of the modernization approach to Russian history, he distinguished several interpretations of modernization: evolutionist, in which the Western model of modernization is considered the norm; pluralist, which assumes the multi-vector and unique nature of modernization in different countries; actor-centered, which takes into account the driving forces of modernization; and regionalist, which substantiates the uniqueness of modernization processes at the sub-country level (Poberezhnikov, 2017). This typology actually represents the main approaches to modernization. Nowadays it is common to speak about modernization theories and different types of transformation and transition of society from traditional to modern.

Modernization Theory for Rethinking Russia’s Past and Future

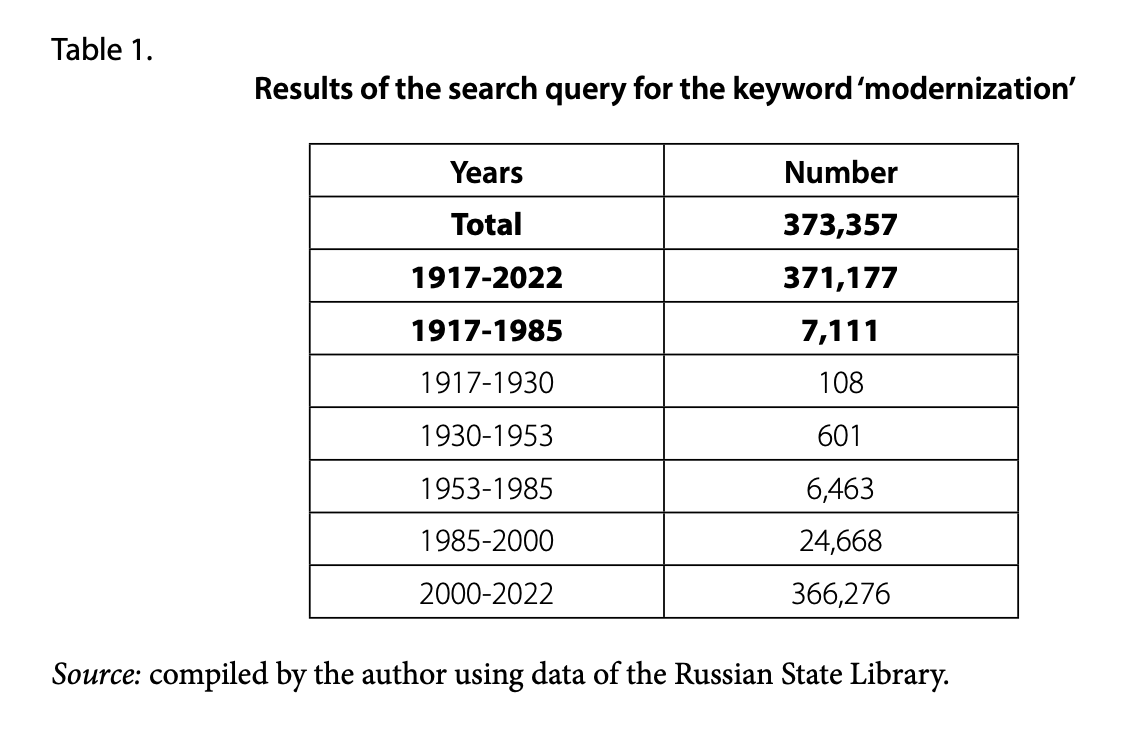

In the 1990s, Russia began to actively explore modernization theory, which actually replaced Marxism-Leninism. Interest in modernization theory reflects not only the search for a new paradigm for understanding what is happening. It is an indication of the point of temporal breach in the comprehension of the country’s past. Search queries for keyword ‘modernization’ in the holdings of the Russian State Library show that from 1917 to 2022 there was a gradual increase in publications on modernization, from a handful of titles in 1910-1930, to dozens in 1930-1953, hundreds in 1953-1985, thousands in 1985-2000, and tens of thousands in 2000-2022 (see Table 1).

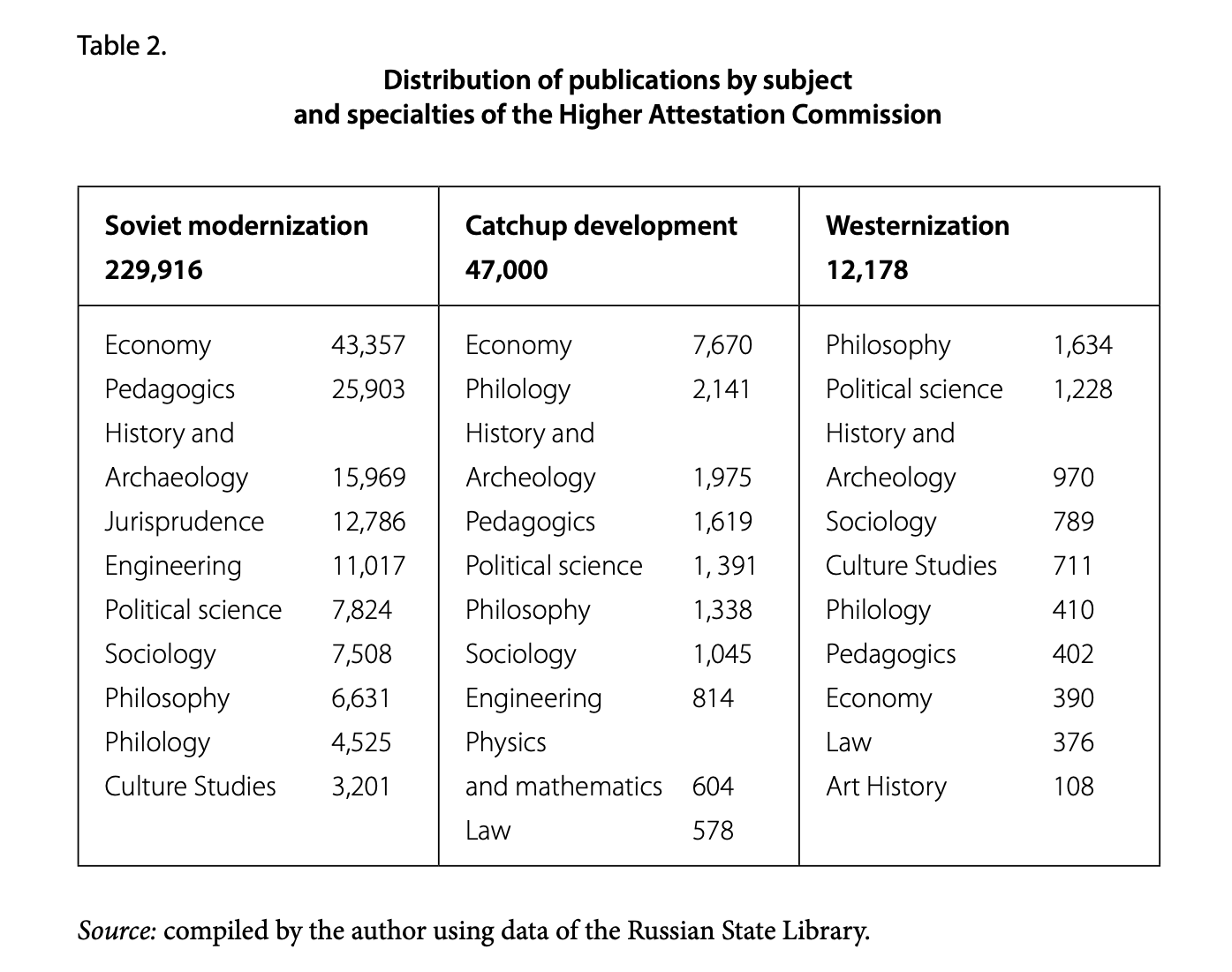

The keen interest in the theory of modernization in modern Russia can be explained by the fact that the country was in the middle of a long historical experiment: capitalist modernization gave way to Soviet modernization. Analysis of the topics of publications shows absolute predominance of “Soviet modernization” over modernization understood as “catch-up development” or as “Westernization.” The greatest interest in modernization theory was displayed by economists and historians (Table 2). The analysis of publications dating back to the Soviet period shows that in the Soviet Union modernization was considered exclusively a theory applicable to understanding Western societies and the development of Third World countries. In the Soviet period, the term ‘modernization’ was used in spheres pertaining to technology and production mainly in relation to the improvement of equipment and the introduction of new technologies (Losev and Gansky, 1961; VNIIEM, 1965).

Today, modernization theory in Russia is used to interpret the Soviet experience of large-scale restructuring of the country. The Soviet Union’s “forced industrialization” of the 1930s is defined by some authors as an “objective need to implement a non-market concept of the country’s industrial technological modernization” (Polyakova and Koltsov, 2021, p. 13), where the system of governance and social relations were subordinate to positivist logic. The concept of modernization provides an excuse for the human cost of Soviet transformations, the problem of forced labor and mass repressions (Gelman and Obydenkova, 2022). Many Russian historians use the concept of Soviet modernization, which is often referred to as “radical constructivism” (Anfertyev, 2020). Today, debates continue over whether Soviet modernization was effective and the only way the political leaders of the USSR could reform the country, and over how much the country needed radical reforms of the early 1990s.

Boris Kapustin, in his analysis of the role of ideology in the collapse of the Soviet system, maintains that in the USSR the Soviet elite implemented a “utilitarian ideology,” which transformed the revolutionary teachings of Marxism-Leninism into the “demagogy of catching up with and overtaking America’ and, of course, according to the America’s rules of the consumer society game” (Kapustin, 2016, p. 77). Kapustin maintains that a gradual convergence could lead to a gradual change of the political system as a result of the “implosion” of the Soviet system and the massive spread of “post-totalitarian habits and rituals” characteristic of consumer society (Ibid, p. 75). Vyacheslav Dashichev, in criticizing the problems of capitalist development in modern Russia, points to the missed opportunities to reform the socialist system without radical reforms (Dashichev, 2011).

Russian researchers distinguish two types of modernization, often in contrast to each other: in the Soviet period—socialist and capitalist, and in the post-Soviet period—liberal and conservative. Roman Lubsky, in analyzing the special features of modernization theory in Soviet and post-Soviet science, formulated the essence of these differences in the following way: “The liberal type of modernization is a type of modernization that is characterized by political participation and the presence of open competition in the system of representative democracy. The conservative type of modernization is a type of modernization characterized by the presence of centralized political institutions that ensure the integration of society by mobilizing a variety of resources for its reproduction” (Lubsky, 2014, pp. 166-167).

It is important that the ideas of Russia’s modernization remain future-oriented. The authors of the collective monograph Russia in Search of Ideology: The Transformation of Value Regulators of Modern Societies believe that ideological modernization in Russia is necessary in close connection with “ethically justified ideas about the desirable present and future not only for individual social groups and Russia as a whole, but also for humanity in general” (Martyanov and Fishman, 2016, p. 14). The authors’ conception of Russia’s modernization within the framework of “global modernity” is based on Ronald Inglehart’s ideas of “post-material needs associated with creativity, cooperation, psychological motives of recognition, trust, solidarity, self-improvement and expansion of the space of individual freedoms of the person.” The authors of the monograph put forward as a central thesis the idea that “any ethically justified goal of modernization nowadays transcends nations” (Ibid, pp. 48, 43).

Thus, in contemporary Russia modernization theory has become in demand in the face of fundamental reforms for interpreting the Soviet past. Also, modernization theory is used to understand the nature of post-1991 reforms in Russia, often in comparison with those of the Soviet period in terms of the goals set and the results achieved. Russian researchers also consider the possibilities for Russia’s further development through the lens of new approaches to understanding the essence of modernization in developed societies. The transition to a post-Soviet society in Russia marks a temporal rupture with the Soviet past, while immersion into the Soviet past for understanding and justifying the strategies being implemented in the present and for choosing the vector of future development confirms Assmann’s ideas.

Different Modernization in Russia and in the EUropean Union

The modernization of post-Soviet Russia was based on a market economy and the emergence of a democratic form of government, which instilled hope that Russia and the EU would achieve mutual understanding and follow similar development guidelines. In the 1990s and the early 2000s, the EU provided Russia with economic and expert-technological assistance, which many Russian and European experts took as another attempt at “Europeanization of Russia” (Flenley, 2022). As part of this assistance, Russia received significant funds to rebuild its economy, governance, and legal and judicial systems. Many Russians in the late 1990s and the early 2000s saw the EU as a model for the future. The Russian political leadership supported this rhetoric. Russia’s accession to the Council of Europe in 1996, which focuses on the protection of human rights, and the recognition of the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights in 1998 were also symbols of the value and normative unity of Russia and the EU during that period.

At first, the EU-Russia relations followed the catch-up development formula, which is often interpreted in Russia as Westernization and compulsion to follow the Western model of development that is alien to it. A vivid example of such reasoning is found in what Alexander Dugin said when he headed the Department of Sociology of International Relations at Moscow State University. In his monograph Sociology of Russian Society. Russia between Chaos and Logos, he wrote in his very characteristic manner that the attitude to modernization in Russia was very specific: “The fundamental feature of Russian society is that its destiny does not coincide with the destiny of Western European society, that we have walked only part of this path. That we have some kind of ‘wrong’ democracy, which the extreme Western liberals often complain about, is our fundamental strength and proof that, while moving for some time in line with the Western European destiny, we have not made it our destiny. This means that at any moment we can jump off the train heading towards a human clone and total globalization.” He also noted: “It is true that we have to look carefully where we should jump off and what is around us. It is our task—the task of sociologists and scientists—to determine where to jump, because otherwise you can jump in the wrong way and hit the head very hard” (Dugin, 2011, pp. 49-50). The donor-recipient relationship formally began to change after Russia was granted a market economy status in 2002, but up until the early 2010s the EU continued to fund programs to help Russia carry out its reforms through the dedicated EUROPE AID fund.

In the 1990s, the EU provided massive reform assistance to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), when the principal decision was made in favor of the Eastern Enlargement of the EU. The nature of the reforms was similar to those in Russia. The important difference was that the EU provided assistance based on different treaty obligations which implied close cooperation and control of changes by the EU institutions (Miroshnikov, 2014). The CEE countries first became candidates for EU accession and later joined the Union. In this respect, Ralf Darendorf’s comment on the importance of “positive intervention in the internal affairs of other states” by the EU is noteworthy. In his opinion, the fulfillment of the Copenhagen criteria[1], was “one of the remarkable and unique aspects of the entire EU accession process,” when “the suspension of the principle of the inviolability of sovereignty, which had been in force for more than 300 years, can be said to have become apparent” (Dahrendorf, 2005, p. 10).

During the EU’s Eastern Enlargement, 11 countries joined the Union seen as a blueprint for a future “peaceful united Europe.” Aleida Assmann believes that European integration embodies the way the EU has learned four lessons of history by implementing four projects: 1) peacekeeping; 2) the rule of law; 3) a truly critical culture of remembrance; 4) human rights (Assmann, 2018). The new EU countries have had a significant impact on expanding the narrative of the past as the basis of European integration. The memory of the dangers of nationalist ideas and the tragedy of the Holocaust were complemented by discussions about the totalitarianism of the Soviet period.

An analysis of the documents that shaped the EU-Russia relations in the 1990s and 2000s shows that the partners had different ideas of cooperation priorities. The EU documents pointed to the importance of democratization, human rights, and modernization of Russia’s political institutions, while for Russia the EU was an important partner in the economic and technological spheres, with human rights not mentioned at all (Deriglazova, 2022a). A clear shift in the understanding of Russia’s modernization vector occurred in the early 21st century with the strengthening of the power vertical and the primacy of national interests over international cooperation and European values, which led to a gradually deepening divide between Russia and the EU. The changes in political institutions stemmed from the changes in Russia’s economic policy. Vladimir Gelman and Anastasiya Obydenkova believe that “the etatist turn in Russian economic policy began in the 2000s with the nationalization of key assets in a number of sectors of the economy, above all, in the heavy industry, and was largely based on Putin’s distrust of private business as such” (Gelman and Obydenkova, 2022, p. 16).

The Partnership for Modernization program between the EU and Russia, 2010-2014, solemnized in the article “Russia, Forward!” by then Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, is a vivid example of how different the understanding of the goals and means of modernization was. Tatiana Romanova and Elena Pavlova highlighted the following points of disagreement: in Russia, “priority is given to the economy, which requires immediate action, while the solution of political problems related to the improvement of democratic institutions is seen as a secondary goal. The EU, on the contrary, proceeds from political achievements (realization of democracy in practice, rule of law, human rights) that determine its normative force” (Romanova and Pavlova, 2013, p. 54). The authors said the EU’s views on modernization were political (politicized), and Russia’s approach was technocratic.

Andrei Kortunov, who headed the Russian International Affairs Council in 2011-2023, in his article marking the tenth anniversary of the Partnership for Modernization in 2020, pointed to significant mismatches in the goals and priorities of modernization in Russia and the EU. However, in his opinion, this program offered a real opportunity for “deep cooperation,” but after 2014 the illusions of closeness between the EU and Russia were gone (Kortunov, 2020). The logic and reasons for the divide between Russia and the EU were explicitly identified by Sergei Karaganov in an interview entitled We Have Used Up the European Treasure Trove in the run-up to the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok in 2018 (Karaganov, 2018). At that time Russia declared its turn to the East after the EU imposed sanctions in 2014.

In the 1990s, the EU provided assistance to post-socialist countries in their transition towards liberal modernization, where modernization of political institutions and democratization of society were important. For EU candidate countries, the fulfillment of the Copenhagen criteria was a mandatory condition for admission. Cooperation between Russia and the EU also started as liberal modernization, but in the early 2000s, Russia prioritized technological and economic cooperation, while refusing to discuss modernization of its political institutions. The EU had no effective tools to influence Russia. The latter, in 2006, formulated the ideas of a “nationally distinctive model of democracy” (Torkunov, 2006) and “sovereign democracy” (Surkov, 2006), which meant a turn away from the liberal modernization model in favor of conservative modernization with a strong state independent of international influence.

Lessons of History and Sustainability of Modernization Practices in Russia

The 2000s marked a gap in the understanding of the goals and strategies of modernization in Russia and the EU, largely based on the revision of the past. In post-Soviet Russia, there was an official break with the revolutionary past of the Soviet Union, which once had inspired many left movements around the world with the ideas of social justice and the possibility of revolutionary transformation of capitalism. This break was symbolized by the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the October Revolution in 2017 under the auspices of the Russian Historical Society, headed by Sergei Naryshkin (RIO, 2017), who is also Director of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service and a permanent member of the Russian Security Council. The October Revolution, which had been regarded as a fundamental event in Soviet discourse, was now labeled as a coup and the seizure of power by radical Bolshevik revolutionaries, and an example of a dangerous split in the political elites and society (Deriglazova, 2018).

Despite the declared break with the past in Soviet and post-Soviet Russia, researchers find continuity of modernization policies and practices. Mikhail Davydov maintains that “after 1861, Russia in many ways consciously de facto implemented an anti-capitalist utopia, according to which in the industrial era, in the second half of the 20th century, it is possible to remain a ‘distinctive’ great power, in other words, to influence the future of the world while rejecting in principle all that let the competitors achieve success: above all, a common civil legal system and freedom of enterprise” (Davydov, 2022, p. 13). Alexei Miller and Natalya Trubnikova believe that the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and modern Russia are ideologically and conceptually different entities, but in form they are empires that sought to find an optimal “new form of being,” “more adapted to modern conditions.” According to the authors, this imperial otherness, manifested in the preservation of the “greatness of the nation,” special interest in the Near Abroad, and the priority of “national interests” and Russia’s sovereignty made close EU-Russia integration impossible (Miller and Trubnikova, 2022).

Dmitry Travin, in comparing the processes of modernization in Western Europe and Russia, emphasizes the fundamental differences between these processes and defines modernization in Russia as “non-modern,” because it failed to bring about the necessary changes in the political system (Travin, 2022). Paul Flenley notes that beginning with the reforms of Peter the Great, the modernization and/or Westernization of Russia with the help of the West meant Russia’s interest in acquiring knowledge and technology in order to make its armed forces and system of government more effective, while European Enlightenment ideas were listened to selectively (Flenley, 2022). Travin cites examples of the same contradiction of Russian modernization during Catherine II’s reign under the influence of European ideas, where the main obstacle to reform was the inability or unwillingness to abolish serfdom (Travin, 2020, pp. 36-40). According to Flenley, this dual and instrumental approach to the West can still be traced in Russian politics and reflects the peculiarities of Russian political philosophy, which sees no contradiction between the power of the state and the freedom of the individual (Flenley, 2022). At the same time, researchers believe that Russia had a real opportunity to overcome “the historical scenario of modern Russian modernization as a catch-up type of modernization” with its characteristic “historical disruptions, backsliding, or stalled reforms, which made archaization of people’s consciousness and behavior inevitable during crises” (Nikolaeva, 2007, pp. 53, 64).

The EU-Russia relations in the field of human rights are indicative of the differences in modernization approaches. The established format of the Human Rights Dialogue (2004-2013) was reduced to regular meetings in Brussels, where Russian and EU officials exchanged accusations of human rights violations (Deriglazova, 2022b), while attempts by the Europeans to expand the platform of dialogue to include non-governmental Russian organizations or to rotate the venue of meetings were blocked by the Russian side (Belokurova and Demidov, 2022).

Maria Freire and Licínia Simão (2015), who have studied modernization discourse in Russian foreign policy, note that this term was actively used in the 2000s, and that gradually the focus on modernization began to be opposed to democratization in relations between Russia and the EU (Freire and Simão, 2015, p. 128). This trend is confirmed by the two latest Russian Foreign Policy Concepts of 2016 and 2023. The notion of modernization appears twice in them. In both documents it is an indication of “modernization of the power potentials” or “modernization of offensive military potentials” of Russia’s adversaries. The 2016 Concept also points to “externally imposed ideological values and recipes for modernizing the political system of states” (Concept, 2016), while the 2023 Concept refers to the need to “modernize and increase the capacity of the Baikal-Amur and Trans-Siberian railway lines” (Concept, 2023), which is reminiscent of the technological use of the term ‘modernization’ in Soviet times.

Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan, in comparing the processes and results of democratic transition of South American and European countries, maintain that Russia has undergone liberalization, but not democratization. In their opinion, to complete the democratic transition, five interacting areas need to be consolidated: active civil society, a relatively independent (autonomous) political society, the rule of law, an efficient state, and economic society (not just a capitalist market)” (Linz and Stepan, 1996, p. xiv). In today’s Russia, none of these spheres is free from heavy government involvement.

Some European researchers note that “Russian modernization remains an enigma and that multiple modernities often coexist at the same time. While the academic debate and literature have mostly focused on economic and societal aspects of modernization, Russia’s modernization cannot be understood without studying its relations with other countries and its position in the international system” (Mäkinen et al., 2016, p. 164). This thesis about the plurality of simultaneously existing types of modernity in Russia is consonant with the ideas of economist Natalya Zubarevich (2010) about the economic development of Russian regions, the analysis of Russia’s relations with its immediate neighbors and far away countries (Romanova and David, 2022), and the special features of the modernization of Russia’s political system (Gelman, 2019).

* * *

Looking at the relations between Russia and the EU through the lens of modernization theories and the concept of temporal breach, one can say with certainty that in the 1990s Russia and the countries of the former Eastern bloc carried out catch-up modernization with reliance on financial and expert assistance from the EU and saw the liberal type of modernization as a benchmark. This development vector was maintained in the EU candidate countries despite the difficulties of the reform period. In Russia in the 2000s, there occurred an ideological turn towards conservatism and conservative modernization. The 2000s saw a steady increase in the well-being of Russians, unprecedented in the last hundred years of Russian history, which created the basis for national consensus on the development policy of the state. In the 2010s, according to Kirill Rogov*[2](2020), there followed a complete revision of development, which included “the absolutization of the concept of ‘sovereignty’; the search for new supports, such as ‘bonds’ and ‘traditional values’ to displace the imperatives of modernization; the construction of ‘nationally oriented elites;’ the actual refusal to recognize the borders that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union; and a decisive turn from cooperation to confrontation in relations with the West.”

The turn towards a strong state relies on certain public demand and disillusionment with the ideas of democracy and liberalism in Russia. Lev Gudkov, in summarizing the results of reforms in Russia, writes that “archaization or traditionalization of politics is not a phantom; it is a new legitimization of power, which is recognized by the majority of Russians. The ideology of state patriotism, which has replaced the ideology of modernization and democratic transition, works as a mechanism for displacing frustrating factors—poverty, humiliation and loss of identity caused by the collapse of the USSR” (Gudkov, 2021, p. 81). Russia’s departure from liberal modernization was a result of what Ralf Dahrendorf called “the collapse of hopes” and “a long journey through the land of sadness” during the perestroika period. Dahrendorf called the process of abandoning liberal values and democracy “creeping authoritarianism” and “the abduction of democracy and the rule of law,” when there occurs gradual nullification of citizens’ participation in running their affairs: the initiative in decision-making is imperceptibly transferred to the executive authorities—to the government, to accountable quasi-governmental organizations and institutions, and to those bodies that are out of control of the known system of checks and balances (Dahrendorf, 2005, pp. 9, 11, 12). According to Boris Kapustin, reforms in Russia have resulted in the emergence of a “depoliticized post-totalitarian individual” and “patriotism of private individuals,” which reflects “the absence of genuine public political life in Russian society, turning politics into the domain and privilege of the upper classes” (Kapustin, 2016, pp. 76, 81).

In Russia, amid reforms, the priority was given to institutional and state goals, a strong state and national interests within the framework of the mobilization paradigm. These priorities are most clearly reflected in the so-called technocratic state-centric approach, where the issues of the quality of governance are considered sovereign and non-negotiable with external actors. At the center of this “state-centric” model is the state and society, and not the individual and minorities. I would agree with Dmitr Travin’s statement that Russia continues “non-modern modernization.” While imitating conformity with the “European cultural product,” Russia imported, processed and consumed it and further began to develop “in a way that is far from the ideals, along which real life had led our country for years” (Travin, 2022, p. 82). It is this development that allows researchers to characterize modernization in Russia not only as “non-modern” or “conservative,” but as “authoritarian.”

In comparing the modernization processes in the EU countries and Russia, we can unequivocally speak about the implementation of different types of modernization—liberal and conservative on the basis of market economy. The EU prioritizes political relations and the quality of political institutions, human rights, and the quality of life—everything that characterizes the polity of post-industrial society with a human orientation. Modernization implemented in the EU can be defined as “humancentric.” Modernization is understood within the liberal paradigm of multiple trajectories and with due regard for the interests of different political and non-political actors as pluralistic and multi-vectored.

If we compare the results of the post-socialist transition of the EU countries that began their transformation at the same time as Russia, we can argue that, regardless of all the problems and imperfections, the new EU countries have increased interest in human rights and individual freedoms in the EU, adding their historical experience to the pan-European debate. Assmann’s new book (2018) addresses the lessons of history and how Europeans are redefining the meaning of the “European dream” through the reinvention of the nation, where human life and rights retain the paramount value. This problem of the present and future of the nation-state in a complex and interdependent world is equally relevant for Russia, which continues the search for a national idea and the construction of a national state, opposing itself to the Western world.

This means that the disruption of relations between Russia and the European Union reflects their different understanding of the essence of modernization, even if they use similar terminology. The disagreements of the early 2000s led to an existential crisis between the former strategic partners, which symbolizes a temporal breach in the modern time regime (to use Assmann’s terms) for Russia and the EU countries, resulting from a look back on their past and realizing its lessons for the present and the future.

The paper is part of the research project titled “Temporal Discourses of Modernity and Projective Realities of the Future in Transdisciplinary Knowledge Perspective» (Project 2.3.7.22) of the “Priority 20230” Program of the Tomsk State University.

The author thanks the journal’s editors and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and remarks that helped improve this article.

The opinions of contributing authors do not necessarily coincide with the views of the Editors.

Anfertyev, I.A., 2020. Modernizatsiya Sovetskoi Rossii v 1920-1930-e gody: programmy preobrazovany RKP(b) – VKP(b) kak instrumenty bo’rby za vlast’ [Modernization of Soviet Russia in 1920-1930-ies: Transformation Program of the RCP(B) – VKP(B) as Instruments of Struggle for Power]. Moscow: INFRA-M.

Assmann, A., 2016. Zabvenie istorii – oderzhimost’ istoriei. [Oblivion of History – Obsession with History]. Geschichtsvergessenheit – Geschichtsversessenheit. Translated from German by B. Khlebnikov. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie.

Assmann, A., 2018. Der europäische Traum. Vier Lehren aus der Geschichte [The European Dream. Four Lessons from History]. München: C.H. Beck.

Assmann, A., 2020. Is Time Out of Joint? On the Rise and Fall of the Modern Time Regime. Translated by Sarah Clift. Ithaca: Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library.

Belokurova, E. and Demidov, A., 2022. Civil Society in EU-Russia Relations. In: Romanova, T.A. and David, M. (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of EU-Russia Relations. Structures, Actors, Issues. New-York: Routledge.

Concept, 2016. Kontseptsiya vneshnei politiki Rossiiskoi Federatsii [The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation]. The MFA of the RF, 30 November. Available at: http://kremlin.ru/acts/bank/41451 [Accessed 4 June 2023].

Concept, 2023. Kontseptsiya vneshnei politiki Rossiyskoi Federatsii [The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation]. The MFA of the RF, 31 March. Available at: http://kremlin.ru/acts/bank/49090 [Accessed 4 June 2023].

Dahrendorf, R., 2005. Iskushenie avtoritarizmom [The Temptation of Authoritarianism]. Rossiya v globalnoi politike, 3(5), pp. 8-12.

Dashichev, V.I., 2011. Teoriya konvergentsii i put’ Rossii: ot oshibok proshlogo k vyboru budushchego [The Theory of Convergence and Russia’s Path: From the Mistakes of the Past to the Choice of the Future]. Prostranstvo i vremya, 4(6), pp. 72-85.

Davydov, M.A., 2022. Tsena utopii: istoriya rossiiskoi modernizatsii [The Price of Utopia: A History of Russian Modernization]. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie.

Deriglazova, L., 2018. The Kremlin’s Revision of Russia’s Revolutionary Legacy. Russia File. Kennan Institute, Wilson Center, 2 February. Available at: http://www.kennan-russiafile.org/2018/02/02/the-kremlins-revision-of-russias-revolutionary-legacy/ [Accessed 4 June 2023].

Deriglazova, L., 2022a. Russia vis-à-vis the European Union: Perceptions and Perspectives for Cooperation. In: Freire, M.R. et al. (eds.) EU Global Actorness in a World of Contested Leadership: Policies, Instruments and Perceptions. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Deriglazova, L., 2022b. The Human Rights Agenda in EU-Russia Relations: From Political to Politicized Dialogue. In: T.A. Romanova and M. David (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of EU-Russia Relations. Structures, Actors, Issues. New-York: Routledge.

Dugin, A.G., 2011. Sotsiologiya russkogo obshchestva. Rossiya mezhdu Khaosom i Logosom [Sociology of Russian Society. Russia between Chaos and Logos]. Moscow: Akademichesky proekt.

Flenley, P., 2022. Europeanisation. In: Romanova, T.A. and David, M. (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of EU-Russia Relations. Structures, Actors, Issues. New-York: Routledge.

Freire, M.R. and Simão, L., 2015. The Modernisation Agenda in Russian Foreign Policy. European Politics and Society, 16(1), pp. 126-141.

Gelman, V.Ya., 2019. “Liberaly” versus “demokraty”: ideinye traektorii postsovetskoi transformatsii v Rossii [“Liberals” versus “Democrats”: Ideational Trajectories of Russia’s Post-Communist Transformation]. Saint-Petersburg: Izdatelstvo Evropeiskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge.

Gelman, V.Ya. and Obydenkova, A., 2022. Izobretenie «naslediya proshlogo»: strategicheskoe ispolzovanie «horoshego Sovetskogo Soyuza» v sovremennoi Rossii [The Invention of “Legacy of the Past”: Strategic Uses of a “Good Soviet Union” in Russia]. Saint-Petersburg: Izdatelstvo Evropeiskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge.

Gudkov, L.D., 2021. Illyuzii vybora: 30 let postsovetskoi Rossii [Illusions of Choice: 30 Years of Post-Soviet Russia]. Riga: ShGL.

Hoffmann, E.P. and Laird, R.F., 1985. Technocratic Socialism: The Soviet Union in the Advanced Industrial Era. Durham: Duke University Press.

Inglehart, R. and Welzel, C., 2011. Modernizatsiya, kulturnye izmeneniya i demokratiya: posledovatelnost chelovecheskogo razvitiya [Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy. The Human Development Sequence]. Moscow: Novoe izdatelstvo.

Kapustin, B.G., 2016. Ideologiya i krakh sovetskogo stroya [Ideology and the Collapse of the Soviet System]. Rossiya v globalnoi politike, 6, pp. 70-81.

Karaganov, S.A., 2018. “My ischerpali evropeiskuyu kladovuyu” [“We Have Exhausted the European Pantry”]. Ogonek, 10 September. Available at: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3719327 [Accessed 4 June 2023].

Kortunov, V.A., 2020. Grustny yubilei: desyat let “Partnerstvu dlya modernizatsii” [A Sad Anniversary: Ten Years of the Partnership for Modernization]. RIAC, 12 May. Available at: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/grustnyy-yubiley-desyat-let-partnerstvu-dlya-modernizatsii/ [Accessed 4 June 2023].

Linz, J.J. and Stepan, A.C., 1996. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Losev, P.P. and Gansky, B.P., 1961. Modernizatsiya bumago- i kartonodelatelnykh mashin za rubezhom [Modernization of Paper and Board Machines Abroad]. Moscow.

VNIIEM, 1965. Modernizatsiya pressovogo i stanochnogo oborudovaniya. [Modernization of Press and Machine Equipment]. Moscow: VNIIEM.

Lubsky, R.A., 2014. Osobennosti teorii modernizatsii v sovetskoi i postsovetskoi nauke [Features of the Modernization Theory in Soviet and Post-Soviet Science]. Prioritetnye nauchnye napravleniya: ot teorii k praktike, 12, pp. 166-167.

Lukyanov, F.A. and Soloviev, A.V., 2019. The Curse of Geopolitics and Russian Transition. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 1, pp. 147–180.

Mäkinen, S. et al., 2016. “With a Little Help from my Friends”: Russia’s Modernisation and the Visa Regime with the European Union. Europe-Asia Studies, 68(1), pp.16-181.

Melvil, A.Yu. et al., 2012. Traektorii rezhimnykh transformatsy i tipy gosudarstvennoi sostoyatelnosti [Trajectories of Regime Transformations and Types of State Capacity]. Polis. Politicheskie issledovaniya, 2, pp. 8–30.

Miller, A.I. and Trubnikova, N.V., 2022. From Past to Future: Rapture and Continuity between Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union. Russian Studies in Philosophy, 5, pp. 369-381.

Miroshnikov, S.N., 2014. Etapy i printsipy vostochnogo napravleniya protsessa rasshireniya Evropeiskogo soyuza [Stages and Principles of the Eastern Direction of the Process of Enlargement of the European Union]. In: Troitsky, E.F. et. al. Vostochnoe napravlenie protsessa rasshireniya ES: problemy i perspektivy [The Eastern Direction of the EU Enlargement Process: Problems and Prospects]. Tomsk: Tomsk University Press.

Mishra, R., 1976. Convergence Theory and Social Change: The Development of Welfare in Britain and the Soviet Union. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 1, pp. 28-56.

Nikolaeva, I.Yu., 2007. Spetsifika rossiiskikh protsessov modernizatsii i mentaliteta v formate bolshogo vremeni [Specifics of Russian Modernization Processes and Mentality in Big Time Format]. In: BG. Mogilnitsky and I.Yu. Nikolaeva (eds.) Metodologicheskie i istoriograficheskie voprosy istoricheskoi nauki. Vypusk 28. Tomsk: Izdatelstvo Tomskogo universiteta.

O’Donnell, G.A. et. al., 1986. Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Comparative Perspectives. Washington: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Poberezhnikov, I.V., 2011. Prostranstvenno-vremennaya model v istoricheskikh rekonstruktsiyakh modernizatsii [Spatio-Temporal Model in Historical Reconstructions of Modernization]. PhD Thesis, Institute of History and Archaeology, Research Institute of the Ural Branch of the RAS.

Poberezhnikov, I.V., 2017. Modernizatsii v istorii Rossii: napravleniya i problemy izucheniya [Modernization in the History of Russia: Trends and Investigation Problems]. Uralsky istorichesky vestnik, 4, pp. 39–40.

Polyakova, A.Yu. and Koltsov, V.V., 2021. Ekonomicheskaya modernizatsiya Rossii: analiz istoricheskogo opyta realizatsii sovetskoi modeli industrialnoi modernizatsii [Economic Modernization of Russia: Analysis of the Historical Experience of Implementing the Soviet Model of Industrial Modernization]. Universum: obshchestvennye nauki, 5, pp.12-14.

RIO, 2017. Itogi revolyutsii 1917 goda obsudili na vysshem nauchnom urovne [The Results of the 1917 Revolution Were Discussed at the Highest Academic Level]. Rossiiskoe istoricheskoe obstchestvo. 29 November [online]. Available at: https://historyrussia.org/sobytiya/itogi-revolyutsii-1917-goda-obsudili-na-vysshem-nauchnom-urovne.html [Accessed 4 June 2023].

Rogov, K.Yu., 2020. 20 let Vladimira Putina: transformatsiya rezhima [20 Years of Vladimir Putin’s Rule: Regime Transformation]. Vedomosti, 8 August. Available at: https://www.vedomosti.ru/opinion/articles/2019/08/07/808337-20-let-putina [Accessed 4 June 2023].

Romanova, T.A. and Pavlova, E.B., 2013. Rossiya i strany Evrosoyuza: Partnerstvo dlya modernizatsii [Russia and EU Countries: Partnership for Modernization]. Mirovaya ekonomika i mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, 8, pp. 54–61.

Romanova, T. and David, M. (eds.), 2022. The Routledge Handbook of EU-Russia Relations: Structures, Actors, Issues. New-York: Routledge.

Martyanov, V.S. and Fishman, L.G. (eds.), 2016. Rossiya v poiskakh ideologii: transformatsiya tsennostnykh regulyatorov sovremennykh obshchestv [Russia in Search of Ideology: The Transformation of Value Regulators of Modern Societies] Moscow: ROSSPEN.

Surkov, V.Yu, 2006. Natsionalizatsiya budushchego: paragrafy pro suverennuyu demokratiyu [Nationalization of the Future: Abstracts about Sovereign Democracy]. Expert, 20 November. Available at: https://expert.ru/expert/2006/43/nacionalizaciya_buduschego/ [Accessed 4 June 2023].

Torkunov, A.V., 2006. Rossiyskaya model demokratii i sovremennoe globalnoe upravlenie [The Russian Model of Democracy and Contemporary Global Governance]. Mezhdunarodnye protsessy, 10, pp. 21–29.

Travin, D.Ya., 2020. Modernizatsiya i svoboda [Modernisation and Freedom]. Saint-Petersburg: Izdatelstvo Evropeiskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge.

Travin, D.Ya., 2022. Nesovremennaya modernizatsiya: “Regulyarnoe gosudarstvo” na Zapade i v Rossii [Outdated Modernization: The “Regular State” in the West and in Russia]. Preprint М-90/22. Saint-Petersburg: Izdatelstvo Evropeyskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge.

Wilensky, H.L., 2002. Rich Democracies: Political Economy, Public Policy, and Performance. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zubarevich, N.V., 2010. Regiony Rossii: neravenstvo, krizis, modernizatsiya. [Regions of Russia: Inequality, Crisis, Modernization]. Moscow: Nezavisimy institut sotsialnoi politiki.

***

[1] The Copenhagen criteria were adopted in 1993 by the European Council as prerequisites for countries to join the EU and included the criteria of democracy, the rule of law, a functioning market economy, and the adoption of EU legislation. See: https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/enlargement-policy/conditions-membership_en

[2]* An individual designated as foreign agent in accordance with the Russian Federal Law of December 30, 2020.