A number of issues related primarily to the resource base have arisen after Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and his staff embarked on a quest for an “innovative breakthrough.” The main problems of developing Russia’s high technology economy include issues of migration and quality of labor resources, an unfavorable tax climate and projects that are highly questionable in terms of real effectiveness.

THE BRAIN DRAIN: VIRTUAL AND PHYSICAL

Essential for the software development sector is the availability of skilled labor migration, which by virtue of a shortage of significant material means of production is de facto the most mobile segment of any economy.

Just one look at these processes at the global market level will be enough to see the obvious intent of developed countries to attract as many highly skilled IT professionals from elsewhere as possible. Quotas for accommodating foreign employees and specialized programs are ways to achieve this goal.

Programs to attract Russian engineers (first and foremost in the IT industry) have been implemented for over a decade in Germany, Ireland, the United States, Canada and Australia. The main importer of high-quality human capital is the United States, where efforts to attract foreign professors, post-graduate students, engineers and scientists have been promoted at the government policy level.

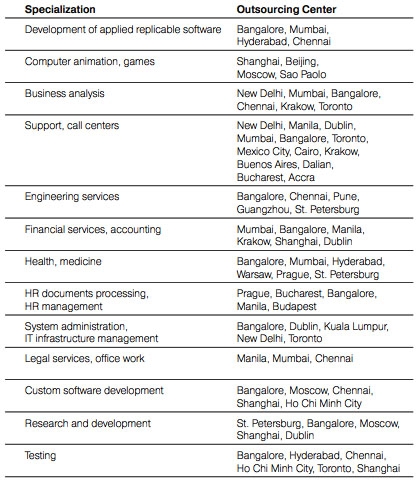

Russia is naturally interested in retaining qualified professionals in order to maintain its competitiveness on the global market – the market of information technology. According to authoritative international rankings, Russia today is in a good position as a country that provides IT outsourcing services. According to the most important parameters for the industry (research and development and engineering), St. Petersburg and Moscow are among the top five cities in countries with developing economies.

Table 1. The world’s rising outsourcing centers

Source: Global Services and Tholons 2009

Moreover, in October 2009 the research firm Global Services included Russia’s Nizhni Novgorod as a future global outsourcing center. The scientific and human potential of Nizhni Novgorod is promising enough for the city to become a major ICT development center, Global Services said in a report. Nizhni Novgorod was put at the top of the list of the top ten contenders for entry onto the rating of Global Services & Tholons. In various world rankings of leading IT service companies in 2009, there were six to eight companies with their headquarters in Russia or positioned as Russian: Auriga, Artezio, Data Fort, EPAM Systems, Exigen Services, Luxoft, Mera and Reksoft.

However, it is too early to claim that Russia is well established as a supplier of not only energy, but also of high-tech products: there are simply too many complex problems facing the industry.

Due to the significant underfunding of human capital development in the education system and the demographic hole resulting from declining birthrates in 1990-2004, the inflow of skilled engineers from Russian universities into the IT industry is getting worse, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Three years before the 2008 financial crisis, Russia’s software industry owed its growing exports largely to foreign skilled employees – primarily to the recruitment of graduates of Russian higher educational institutions from other CIS countries, as well as the physical migration of software developers from these countries. Moreover, there was the “virtual” method of overcoming the personnel shortage – Russian companies created remote centers for software development in the very same countries of the CIS (mainly in Belarus and Ukraine) and also in Eastern and Central Europe and Southeast Asia.

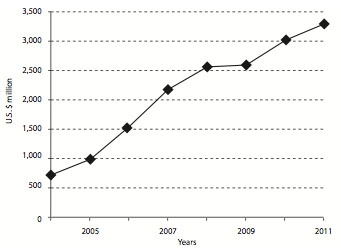

The crisis reduced the need for employees for about 18 months, during which the export of software products and services for their development remained in a state of unstable equilibrium. Exports did not fall, but showed no significant growth either, which was typical of the Russian software development industry for the decade up to 2008 (by 30-40 percent per year).

The situation concerning Russia’s human resources began to change starting from the second quarter of 2010. The global IT market has rebounded and the Russian market is getting better as well. The sales curve for software developers has started to climb, and Russian companies are again faced with a shortage of workers. According to an annual survey by RUSSOFT, at the end of the first quarter of 2010 the salaries of IT specialists in Russia had reached pre-crisis levels, while the number of positions grew to a value equal to the number of job applications. The industry urgently needed a source for more workers.

Fig. 1. Russian software exports

Source: RUSSOFT

While Russia attracted workers from CIS countries, Russian software developers continued to leave the country. Three to five years before the financial crisis the physical migration of engineers remained in balance: while some left, approximately the same number arrived (the number of those on either side varied at a level of several thousand). The situation became worse during the crisis because it led to the collapse of the Russian IT market (according to the IDC, the slump was as bad as 37 percent in U.S. dollar terms). Many companies operating on the Russian market were forced to cut staff and stop recruiting new engineers. According to data provided by Russia’s National Association of Innovations and Information Technology Development (NAIRIT), the number of young professionals who left Russia in 2009 was up 3,000 from 2008.

Another form of migration is when the development centers of foreign companies in Russia hire Russians. In contrast to physical migration, the virtual one not only poses no danger to the country, but, on the contrary, it holds back the departure of specialists in times of crisis. In addition, employment at the laboratories of foreign companies can help raise a class of Russian programmers who are very familiar with global business culture, with organizing technological and management processes, and the practices of training top class specialists. Having undergone such schooling for several years, former employees of global companies’ development centers often move on to senior positions in Russian companies or establish new businesses in Russia.

RUSSIAN IT: PROBLEMS AND SOLUTIONS

In 2010, there were two major issues in the Russian high-tech industry:

Where to get new qualified engineers to meet the growing needs of the world and Russian IT market?

How to remain competitive in an environment after January 1, 2010? The government abolished the unified social tax (UST) at the beginning of 2010, a benefit for exporters in 2008–2009, replacing it with social transfers. This was a move that significantly increased the tax burden on IT companies (social welfare payments increased from 14 to 34 percent over two years for these companies).

It is impossible to solve the problem of personnel for the IT industry by inviting guest workers from other countries. The arrival of foreign nationals and immigrants with a Russian background would require substantial spending on resettlement. For example, those arriving from Europe or the U.S. will require higher pay than by Russian standards (a programmer’s salary is four times as high in the United States than in Russia).

In addition, even if such specialists come to Russia they will have to work in substantially worse economic conditions.

Due to the industry’s enormous efforts and the president’s continued support, the adoption of federal law No. 272 in October 2010 kept insurance premiums at 14 percent for software exporters, as well as for companies that operate on the Russian market. In this case, however, conditions became worse for small business owners (including software development companies with fewer than 50 employees), for which premiums increased from 14 percent to 26 percent. Moreover, after two years there will be another premiums hike to 34 percent. Conditions are not very good for the commercialization of scientific research and for attracting venture capital. There are customs and other administrative barriers hindering the import of high-tech equipment and for posting international payments – not to mention such important factors as the overall quality of life, urban infrastructure and security. In terms of these parameters Russia lags far behind the developed and even some developing countries.

OBSTACLES TO MAKING RUSSIA A DREAM COUNTRY

President Medvedev’s proposal to make Russia a dream country, or a very attractive place for doing business (in a speech delivered at the opening of the St. Petersburg Economic Forum on June 18, 2010 – Ed.), was a strong emotional appeal to international business and the right gesture. Russian innovative companies are as interested in such a state policy as their foreign counterparts.

However, there is a list of major obstacles preventing the Russian economy from attracting business to its high-tech sector:

- corruption, especially in the customs and law enforcement agencies;

- a lack of a system to support high-technology exports;

- excessive government involvement in business and a low level of competition, especially when it comes to distribution of government contracts;

- an ineffective system of financial accounting which is incompatible with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS);

- a lack of a support system for import substitution in critical sectors;

- an ineffective system of training;

- an inefficient system of financing R&D and scientific activities;

- the incompatibility of legislation concerning intellectual property rights protection with international practices;

- an inefficient tax system.

What could be done to improve Russia’s economic system? What improvements could be made to the high technology sector, using its existing capabilities, but without radical reform or restructuring of public administration? We propose the following:

- eliminate customs duties and taxes on imported hardware and electronic components, as well as manufacturing equipment and technologies for which there are no Russian analogs. Such items are imported to Russia in single samples for technological purposes (testing, development of software for management systems, etc.);

- declare high-tech exports a priority of Russian economic policy and launch an ambitious program to support high-tech exports from Russia;

- introduce international accounting and financial reporting standards; reduce currency controls with respect to contracts providing for the inflow of currency into Russia;

- change educational policy; make the development of the education system a priority, increase teachers’ salaries and their social status, step up competition for university positions, create incentives to transfer the results of scientific research to universities and businesses;

- change the way the government funds R&D; create a tool for the commercialization of R&D, such as something similar to ITRI in Taiwan (the Industrial Technology Research Institute – a national research and education center whose mission is to improve the competitiveness of Taiwan on the global market through the development of new technologies and training specialists for high-tech companies). Introduce the export potential of manufactured products (services) as the main criterion in determining the winners in bidding contests;

- change the system of intellectual property rights protection, and integrate these changes into the global system of copyright protection;

- ease procedures to attract investment at the early stages of business development; create a friendly environment for private investment in establishing and developing new innovative businesses;

- promote competition and reduce the state’s share in the market, especially in capital-intensive industries;

- promote import substitution in those areas of governance critical to the information security and technological independence of Russia; unify and standardize IT systems being used there;

- promote the development of the national IT industry through the introduction of large IT projects at enterprises co-owned by the state, where domestic producers would have an advantage in tenders on the condition of their export experience or export potential of the solutions they propose;

- promote the development of the national IT industry through large-scale government programs for the conversion of government services available to the public into an electronic format; attract Russian IT companies in the capacity of contractors.

Let us dwell on some of these items in greater detail. First of all, on creating a tool for commercializing R&D – it is assumed that the government has already taken the necessary steps in this direction. But how effective are these steps?

SKOLKOVO: A CHALLENGE TO SILICON VALLEY?

The highest profile government project for supporting the high technology sector is a plan to build the research center Skolkovo, outside Moscow. The famous Silicon Valley – the global center of high-tech research and development – also began with state support, more precisely with large government contracts (mostly for the defense industry) placed among enterprises affiliated with one cluster having a common alma mater – Stanford University. Such “innovation hothouses” exist in all countries that want to be high-tech leaders: the UK, Ireland, Canada, China, Taiwan, India, France and Germany. However, the Skolkovo innovation center has raised many questions – primarily the feasibility of this expensive project the way it was presented to the public at large.

Many IT companies do not need Skolkovo’s Garden of Eden. Far more important to them are financial instruments (for example, lower taxes), mechanisms of interacting with other businesses, institutions and real investors and the selling of ideas. All this can be arranged in a long-distance mode. Given the modern level of technologies, there is no special need for close proximity to each other.

In Skolkovo it will be especially important to maintain the principle of ex-territoriality – “virtual registration” of companies inside the incubator. These companies should not be concerned with fighting over floor space at Skolkovo, but with developing technologies. Moreover, human resources in the regions are much cheaper. Most IT companies will never move their main office to the research center – this would be tantamount to losing many valuable employees for whom job conditions are important. It turns out that the physical presence of companies at Skolkovo will be needed only for the occupancy of space at business centers.

The tax breaks promised for companies in Skolkovo are very important: the remuneration of employees constitutes up to 80 percent of the cost of innovation and IT companies, and lower social security payments will stimulate the industry’s development. But it is clear that in order to achieve the goals of modernization, the benefits for the IT industry should be established on a national scale, rather than inside a separate research compound. The same is true of easing customs legislation and the visa regime for foreign professionals. If benefits for the residents of Skolkovo are tangible, then one is likely to see companies lining up for the chance to ease the fiscal burden. Control of this queue is another potential niche for corruption. Without building transparent, universally comprehensible rules for innovative companies to make their way into the science cluster, this project will run the risk of becoming, at best, simply a source of good ideas and cheap labor for developed countries, and at worst – another Moscow super business center.

ELECTRONIC PUBLIC SERVICES: A CHANCE FOR THE IT INDUSTRY

Along with such ambitious projects as the research cluster, the government could offer the Russian high-tech sector participation in another enormous project – the promotion of public services in electronic form. State orders for such products can significantly boost the development of the IT industry in the country.

Russia lags far (if not catastrophically) behind developed countries in terms of government services available through the Internet. The federal program Electronic Russia is several years old, but there has been no significant progress in this area, which has been declared a national priority.

The national portal http://www.gosuslugi.ru has recently emerged, but it remains largely a reference resource – the number of public services actually present and running on the website is still very small. In addition, the operation of this service has drawn too many complaints for it to be considered an effective tool to offer real public services on the Internet. There are portals of public services for individual cities, also with a tiny amount of actual working functions. For example, at the portal of public services in St. Petersburg one can only put one’s name on an electronic waiting list to apply for a marriage certificate or child benefits.

Meanwhile, progress made by Russia’s nearest neighbors, such as Estonia and Kazakhstan, has shown that the problem can be resolved. After all, these countries started at the same technological level as Russia did, but Estonia today has converted more than 700 public services into the electronic format (in the four years that the state program has been in operation). Kazakhstan has created and operates a single work-flow system for public institutions – such a level of electronic integration among state power agencies in Russia is simply impossible to imagine.

According to the World Economic Forum, Russia is 80th on the list of readiness for the introduction of electronic public services, between Trinidad and Tobago and El Salvador.

Why is this? There are several systemic causes for Russia’s lag behind even its former “sister republics.”

First, Russian legislation still lacks precise rules for electronic interaction between the public and the government. The main problem is the absence of legal working rules with respect to the use of the electronic digital signature – the EDS. An inability to work with EDS and to use it to identify individuals poses a major problem in relations between bureaucrats and society – the need for a client to appear in person at this or that office to receive a public service. As a consequence there are long lines, low efficiency among state institutions and wasted time.

Meanwhile, all the necessary facilities for the full-fledged use of EDS are in place across the nation; the legislative base is the stumbling block.

Second, Russia’s numerous regulators and law enforcement agencies hinder the work of the e-government. Any public or commercial organization that needs personal data for servicing the public is forced to undergo complex and lengthy inspections, licensing and certification. They take away companies’ considerable resources, both human and financial.

Third, even in cases where the authorities concerned decide in favor of providing a new service in electronic form, corruption mechanisms ruin the good intentions. Quite often, instead of real work one can see the same eternal carving-up of allocated funds among the interested stakeholders, while the project proper only gets “what is left over.” As a result, it is easier and faster for people to receive public services the old way.

Fourth, the provision of public services electronically is complicated by the lack of unified formats and standards of documents. Moreover, large agencies often try to create their own formats, kept away from the others. The lack of communication between databases of individual agencies is a big problem – officials jealously guard their available personal data on individuals and legal entities from intrusion by other government structures. As a result, the speed of application processing and transmission of documents is much slower than it would be if the same data base existed for everyone.

Fifth, local officials are not very qualified and many require further training. Providing public services in electronic form requires a certain level of computer literacy. Unfortunately, a vast number of Russian civil servants still do not have good practical computer skills.

Despite the obvious difficulties, though, the market of electronic public services is growing, and in upcoming years the potential to work on it for domestic IT companies will be significant.

First of all, Russian IT businesses will be able to make money on such large-scale projects as the planned launch of the unified e-card for all Russians. The authorities, in order to identify people and store personal information, plan to issue a personalized e-card to every Russian citizen. This e-card will store information for bank transactions, paying travel expenses, health care, pensions and for any other similar operation.

It will take 150 billion to 300 billion rubles and five years to create a single electronic card, according to such officials as Sberbank CEO German Gref. This ambitious project can be implemented only by an alliance of Russia’s largest system integrators – no single company will be able to successfully solve such a problem alone.

It should be noted that in 2010 the government took several steps aimed at promoting informatization throughout the country. President Medvedev signed Federal Law No. 229, dated July 27, 2010, which, among other things, provides for the possibility of invoicing in electronic form and of using the electronic digital signature. The legislative framework has not been finalized yet – in order to start exchanges in electronic invoices, the rules of their transfer through communication channels must be devised first. The possibility is still being considered of submitting electronic documents to Russian arbitration courts. When this law is fully in effect, the efficiency of enterprises and fiscal authorities will increase significantly: at the national level the labor costs of information sharing will decline, and so will the number of errors resulting from “manual input.” For businesses, these innovations will mean a colossal reduction of paper work and accelerate the workflow.

An important event last year was the adoption of GOST R standard 53898-2010 “Electronic Document Management Systems. Interaction of Document Management Systems. Requirements for Electronic Communication.” Establishing uniform standards for electronic document exchange will give an impetus to the inter-departmental integration of electronic document management systems in state agencies. Consequently, the market of providing electronic government services will develop.

On July 1, 2011, legal amendments will enter into force prohibiting agencies from requiring that their clients provide any additional information or documents, if the necessary certificates and documents are already available at any government agency.

All these measures will enable players in the Russian IT market to participate in the development of e-government services. But for the IT industry to receive an additional incentive to participate in these large-scale projects, the state needs to ensure several conditions:

- provide equal and open access for industry participants to government contracts and projects, and guarantee fair competition in public bidding contests and tenders for the supply and development of IT solutions;

- bring the legislative framework into full conformity with the realities and needs of the information society, in particular, ensure the possibility for the public to use the electronic digital signature upon receipt of government services in electronic form – i.e. to ensure the full legal significance of EDS.

- reduce the role of state regulators in establishing rules and permits for work with personal data and confidential information. Furthermore, simplify procedures for the licensing and certification of companies and software products for work with the data of individuals and legal entities.

In the near future Russian citizens will receive their passports and driving licenses by mail, business people will be able to register firms within two hours without leaving their computer, such as the way it is done in Singapore, and Russia’s IT sector will be one of the world leaders. This is not a daydream; everything will be possible if only the government shows genuine interest.