Skepticism is increasing in the post-Soviet space about the Eurasian Union (EAU). Similar to doubts surrounding the European Union, the public, government officials, and business and expert communities are growing less enthusiastic about the success of the Eurasian project. As euphoria over the launch of the Customs Union and the Common Economic Space dies down, attitudes towards the Eurasian project are becoming progressively sober and public support for the emerging Eurasian Economic Union is shrinking.

People have criticized attempts to reintegrate post-Soviet space ever since the break-up of the Soviet Union some twenty-three years ago. Critics have expressed doubts over the objectives and methods of the unification processes, both from inside (in the three core countries of the integration project – Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus) and out. However, the current skepticism is markedly different: it is swelling as an organic part of the project, which now encompasses the Customs Union, the Single Economic Space, and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAU), and both its supporters and opponents recognize it as a fait accompli.

Skepticism towards the Customs Union is still in the nascent state. A sociological survey (the Eurasian Development Bank’s (EDB) Integration Barometer) found that an average of 68% of people living in EAU member-states supported that organization in 2013 (down two points from 2012). Compared to the 50% support for the European Union registered by a Eurobarometer pan-European survey, this means that Eurasian integration still has some credibility and durability. Yet the critical perception of the Customs Union, the Single Economic Space, and the EAU (the latter is still in the process of formation) is likely to increase in the next several years. And we all have to reconcile ourselves to that fact.

THE EVOLVEMENT OF EURASIASKEPTICISM

This article uses data provided by the Integration Barometer project, which is based on research conducted by the Eurasian Development Bank on a regular basis. The surveys pose a series of diverse questions, ranging from the commodities people prefer in post-Soviet countries to investment partners in educational/socio-cultural institutions. Thus, the surveys mirror annual shifts in the moods of people living in the CIS. These indicators help to identify which spheres of integration are doing well and which are showing signs for concern.

One of the central points of study is public opinion about the feasibility of accession to the Customs Union and the Single Economic Space, and the overall perception of those associations. In the polls, the wording of questions differs depending on whether a country is a member of a particular association or not. Consequently, people from member-states were asked about their attitudes towards the Customs Union and the Single Economic Space, while respondents from non-affiliated countries were asked about the possibility of accession to those organizations.

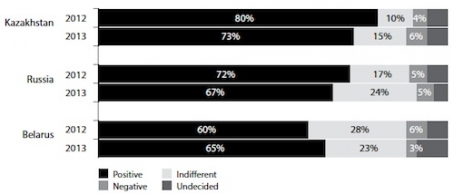

The public’s approval of the Customs Union and the Single Economic Space is relatively high (see Diagram 1): in 2013, support in Kazakhstan stood at 73% (down 7% from 80% in 2012). The drop in support was due to an increase in the number of local residents who expressed indifference to Kazakhstan’s participation in both associations (15% in 2013 compared to 10% in 2012). Six percent responded negatively about joining either organization.

In 2013, support in Russia for participation in both associations dipped to 67% from 72% in the previous year. In addition, Russia showed the biggest growth of indifferent attitudes, which rose to 24% from 17% in 2012. The percentage of Russians treating these processes negatively remained at 5%.

In Belarus, support increased for membership in the Customs Union (to 65% from 60%) and grew closer to the level of support in Russia. This change occurred amid an economic rebound and financial aid from Russia. The percentage of Belarusians indifferent to the Customs Union dropped to 23% from 28%, but, like in Russia, support still remains relatively high. The percentage of those who responded negatively towards integration fell to 3% from 6%

Diagram 1. Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia formed a Customs Union and abolished customs duties between the three countries. The three countries also formed a Single Economic Space, which, in essence, is a common market. What is your attitude towards that decision?

Source: Integration Barometer

Other questions revealed a more critical approach, especially in the categories of commodity preferences, science, technology, and education.

- Compared to 2012, goods produced in CIS countries were in less demand among Russians (12%) and Belarusians (8%) in 2013. “Other countries,” i.e., countries outside of the Eurasian Union and the CIS, were named as the most preferable sources of foreign investment. Investment by post-Soviet neighbors (which actually means Russia) was not a priority. One possible explanation for this is that Russian investment is not associated in the public mind with technological progress or industrial modernization (although the actual situation is much more nuanced. See the data on Russia’s diversified direct investment in the CIS provided by the EDB’s another annual report on the Monitoring of Mutual Investments).

- A question about priority partners in science and technology has revealed a similar picture. Respondents from all CIS countries mentioned Japan, the U.S., and Germany as priority partners. One of the reasons may be the perception of Russia as a country that has lost many of its leading positions in science and technology over the past two decades.

- Negative long-term trends are characteristic of educational exchanges. Although many recognized educational centers in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kiev, Minsk, Almaty, Yekaterinburg, and Omsk could compete successfully with Western universities in the 1990s in the cost to quality grounds, current polls suggest that those institutions have lost that advantage. Also, grassroots chauvinism, which is another factor unrelated to the quality of education, still impacts Russia. Of course, one should reckon with persistent trends in education that relate to the two post-Soviet decades, not to the short history of the Customs Union.

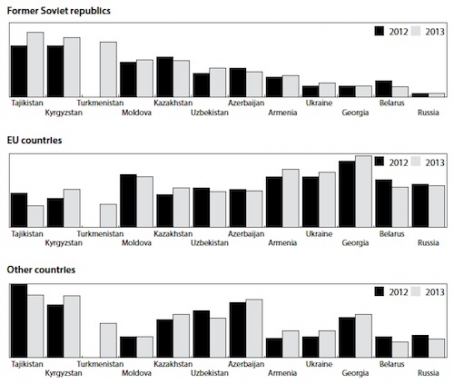

Diagram 2. To which of the countries below would you like to go to study or for other educational purposes (or to send your children for study)?

Source: Integration Barometer.

From this point on, in diagrams depicting the categories “Former Soviet republics,” “EU countries,” and “Other countries,” the indicators account for the percentage of respondents who named at least one country in an appropriate category. For instance, in this diagram, 52% of Tajiks mentioned at least one former Soviet republic; 18% at least one EU country; and 51% at least one “other” country (see data for Tajikistan in 2013).

Preferences indicating the most attractive countries for cooperation in science and technology are especially important because they directly relate to long-term strategic competitiveness. Therefore, it should be alarming that the CIS population shows little interest in neighboring states in these areas.

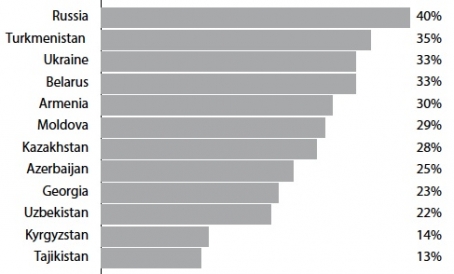

Equally worrying in terms of the Eurasian integration project is the relatively high level of “autonomous approach” to development with some post-Soviet countries, which is manifest in the lack of respondents’ interest in any country on the list (see Diagram 3). The term “autonomous approach” implies that people concentrate on their home countries’ internal problems and resources. They show a relative lack of interest in interacting with the world in a wide range of areas, including trade, investment, and culture. The general tendency is: the wealthier a country, the more inclined its citizens are to develop on their own. Kazakhstan, which is open to the outside world, is an exception to that rule.

Diagram 3. The level of public interest in autonomous development in countries taking part in the project (the mean value of the total percentages of ‘No such countries’ and ‘Undecided’ in answers to questions asked in each country)

Source: Integration Barometer

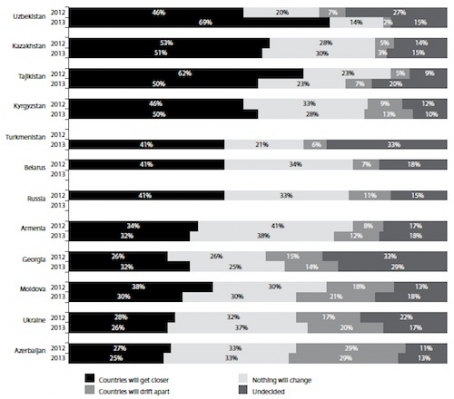

Overall, people living in Customs Union countries and their neighbors are fairly optimistic. For instance, three-thirds or more respondents in the three core nations believe that the integration project will either develop further or maintain current achievements, but the project will definitely not collapse.

Diagram 4. Do you think there will be a rapprochement or estrangement among CIS countries in the next five years?

THE EXPERIENCE OF EUROSKEPTICISM

From the beginning skepticism has accompanied the discussions of post-Soviet integration. While Eurasiaskepticism is no more than a year old, concerns about the EU have been around for a long time. Thus, it makes sense to compare the two phenomena on the basis of sociological data.

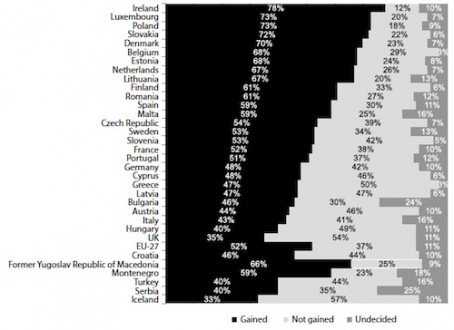

Eurobarometer polling conducted in EU countries reveals a lower percentage of those who approve of integration. People living in incumbent EU member-states gave a relatively positive assessment of the gains in their respective countries from involvement in the European common market, yet the share of positive answers does not exceed 50% (see Diagram 5). It is noteworthy that the level of approval was much higher in the first half of the 2000s, while support dropped later during a financial crisis in the eurozone. The number of negative assessments now approaches the amount of positive assessments in Britain, Hungary, Italy, Austria, Greece, and Cyprus, and sometimes the results are even higher. Thus, the public no longer assesses all of the blame to national governments for short-sighted fiscal policies and bloated non-production assets, but blames Brussels instead.

Overall, the perception of economic integration within the post-Soviet space is more positive than within the EU. However, we should bear in mind that since the questions of the two “barometers” differ, the responses can neither be directly compared nor provide an accurate analysis. Importantly, Europeans were asked about what they had already gained from the EU. Naturally, during the economic crisis Europeans were not inclined towards favorably assessing the impact of integration on their lives. Simultaneously, respondents from post-Soviet countries were asked about their general attitudes towards the establishment of the Customs Union. Since it has not had a significant influence on their lives so far, their judgments were based on more general perceptions (“It is a good and appropriate thing to be together and be friends.”)

Diagram 5. Overall, has your country gained or lost from membership in the EU (the Common Market)?

A similar conclusion can be drawn by comparing the results of polling in countries that are not members in associations. Macedonia and Montenegro were the only two of the six candidate countries in November 2012 where more than 50% of respondents spoke favorably of participating in the European common market. In the case of Turkey, the figure accounts for decades of unsuccessful attempts to join a united Europe. The Serbian response was mostly negative in the wake of the EU’s support for the forces that had broken up the former Yugoslavia. Icelanders reacted to the ‘hard landing’ of 2008. As for post-Soviet space, the only negative assessments came in Azerbaijan, where 53% of respondents indicated that they would not like to join the Customs Union, while only 37% supported such a move. This is a consequence of the Karabakh syndrome. In other CIS countries the percentage of those who support economic integration was much larger and reached three-thirds of the population in some cases (72% in Kyrgyzstan, 75% in Tajikistan, and 77% in Uzbekistan).

REASONS FOR SKEPTICISM TOWARDS THE EURASIAN UNION

Without claiming to be exhaustive, our study suggests some possible reasons for the skeptical attitudes towards the Eurasian project (a more detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this article).

First, at the grassroots level a common question is: “What particular benefits does the Customs Union have in store for me personally?” This attitude towards Eurasian integration is growing, while the answer appears to be quite simple for an average Belarusian family (“Just look at our utility bill.”). By contrast, it is much harder for a Kazakh or Russian family to answer that question.

Second, the positions of Russian companies have grown stronger on the common market. That has become an irritant for small and mid-sized national manufacturers, especially Kazakh enterprises.

Third, governments and big business in partner countries are not happy with several non-tariff barriers that protect the Russian market. Moreover, it is difficult for outsiders to gain access to Russian pipelines and railway infrastructure. Countries are also apprehensive about the potential equal access to state procurement. Russian businessmen are dissatisfied with non-tariff barriers in Belarus and Kazakhstan, but, due to the incomparable size and significance of those markets, this discontent is not expressed explicitly.

Fourth, regardless of real successes and failures, an economic association with an imbalance in participation (such as the Customs Union, Mercosur, and NAFTA) implies inevitable surges of negative sentiment towards a dominant economy. Even with real achievements, negative sentiments are inescapable towards Russia, which accounts for 75% of the organizations’ population and more than 85% of total GDP. In the case of the Customs Union, widespread apprehensions of a return to the Soviet past aggravate this trend.

PREVENTIVE CARE OF EURASIASKEPTICISM

At this point there are no grounds for panic regarding the growth of skepticism towards Eurasian integration. In general, public assessment is encouraging of the current state and prospects for mutual cooperation and integration in the region. At the same time, a favorable ‘case report’ of the Eurasian integration project does not mean all is well. One of the problems is the low level of awareness of the realities and opportunities of Eurasian integration among the public and business community.

In this context, more active promotion of information is needed about integration processes in the nascent Eurasian Union. In the absence of preventive information measures, other forces are slamming the Eurasian project with negative images and labels to impede integration (for instance, the slogan “Eurasian Union=Soviet Union 2.0”). At the same time, the ideology of Eurasian integration consists of pragmatic economic benefits offered on the basis of equality and respect for the sovereignty of the countries engaged in it. Only through persistent and systemic efforts by the entire information structure of the Eurasian integration project can there be a positive shift in the perception of the union. The public needs to be educated about what the Customs Union and the Single Economic Space are; how the Eurasian Economic Commission works and what is behind the establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union.

The EU has been more than just successful in this respect and has paid a great deal of attention to self-positioning in the international arena. There are plenty of instruments for promoting Europe’s economic interests. A powerful informational component based on grants also exists in the Eastern Partnership project.

Public promotion of the Eurasian project is necessary in order to enhance its attractiveness within and beyond the association. The partners in Eurasian integration are only just embarking on this journey. Some organizations in Russia, like the A.M. Gorchakov Foundation for Support of Public Diplomacy and the Russian Council for International Affairs, can serve as good examples. But this is not enough: the bulk of systemic work should be shifted to the mass media. In this context, it is very important to refrain from substituting informational work with propaganda that fuels a strong reaction in post-Soviet citizens. It is quite obvious that the giant project has its weak points. Situations regularly emerge involving short-term negative effects that are necessary to secure long-term positive gains. Hushing them up would be counterproductive.

* * *

Skepticism is normal in any project development and it will naturally continue to accompany the Eurasian integration project. Regular monitoring of public opinion will help uncover sore points that demand special efforts. In the short term, it is crucial to stage a prudent information positioning strategy. Furthermore, in order to curb skepticism towards the Eurasian integration project, systemic preventive measures are needed, such as an earnest and well-balanced dialogue with the public and business community. In the long term, integration will be successful if it works for the benefit of the people. That requires a consistent policy aimed at boosting profits along with productivity, and a search for promising niches in the international division of labor for union member-nations.

In any case, we will have to get used to Eurasiaskepticism. It will be around for the long haul.