This article summarizes the main points of the report “Towards the Great Ocean-3. The Creation of Central Eurasia. The Transit Potential of Russia, Silk Road Economic Belt, and Co-development Priorities for Eurasian Countries.” The report was prepared under the auspices of the Valdai International Discussion Club by a team of scholars led by Sergei Karaganov. Timofei Bordachev supervised the preparation of the report.

The year 2014 saw Russia turn towards the East, establish a genuine strategic partnership with China, and embark on a radical transformation of its relations with the West. These historic changes coincided with the beginning of a new stage in Eurasian integration and the advancement of several strategic initiatives by Beijing. The most important of them is the Silk Road Economic Belt concept, a large-scale investment and transport/logistics project, announced in 2013.

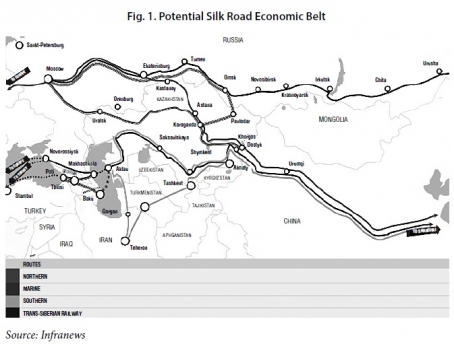

The first steps to implement the initiative were made in November 2014, when the $40-billion Silk Road Fund was set up to provide investment support for the project. The Chinese project aims to turn the region into a world center of economic growth and global influence. The Silk Road will link north-western regions of China with markets in Europe and Western Asia. However, the significance of the project is not confined entirely to the transportation of goods; it is a strategic plan for the region’s development through the creation of new infrastructures, industries, trade, and the services sector.

Moscow needs to take a proactive stance on this Chinese initiative, because its implementation will affect prospects for Russia’s continued leadership in the region, and its position in the world in general. Russia needs to cooperate with China in creatively developing the Belt project and broadening its potentialities through interaction with the Eurasian integration project. On this basis, Russia will not only give a new impetus to its own economic development but will also strengthen the Eurasian Economic Union with the inflow of Chinese investments in Kazakhstan and Central Asia, which will strengthen their social and economic stability.

Geographically, Russian and Chinese interests overlap, and there are no serious differences between the two countries. The policies of the United States and its allies are pushing Moscow and Beijing towards each other and prompting countries in Central Eurasia to realize that they need to work together to ensure their long-term security and sustainable development. There is emerging a “Central Eurasian momentum” – a unique concourse of international political and economic circumstances for tapping the potential of cooperation and joint development of countries in this macro-region.

THE FOUNDATION FOR EURASIA’S FUTURE

As the cradle of many nations and civilizations, Eurasia saw the birth and triumph of several great empires – the Chinese, Mongol, Russian, and Timurid empires. Despite its glorious history, Eurasia in the 21st century is not a single political and economic entity. It is torn between Europe and Asia, it has no face of its own or a supranational identity, and viewed by many as an area of competition between the leading powers in the region – Russia and China.

This factor provokes external forces to destabilize the situation in the region, drive a wedge between Moscow and Beijing, and make other Eurasian countries choose between allegedly mutually exclusive alternatives. However, none of the differences discussed by political analysts and scholars is objective or insurmountable. Moreover, the ancient land of Eurasia offers unique opportunities for developing safe and highly profitable transport and logistics hubs and corridors that connect production and consumption capabilities of such global development centers as Europe and Asia.

The strategic objective of regional multilateral cooperation is to turn Eurasia into an area of joint development, as intensive as in the European Union. Eurasia can have a say in global affairs only if it implements large-scale economic projects that will unite the continent. Cooperation is also required to counter common cross-border and outside threats. These include high volatility of hydrocarbon markets, sanctions as a phenomenon of the new political and economic reality, drug trafficking, environmental migration, common threats associated with the deteriorating situation in Afghanistan and the Islamic State factor, and the general threat of Islamism, which China sees particularly in separatist sentiment in Xinjiang. To address these problems, Russia, China and other countries participating in the Belt project could use more actively the mechanisms created by the Collective Security Treaty Organization and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Siberia, Kazakhstan, Central Asia, and western provinces of China are the natural center of Eurasia. These territories are rich in natural resources, including oil, natural gas and rare-earth non-ferrous metals, and provide the shortest, most cost-effective and safest transport links between the two colossi of the world economy – Europe and East/Southeast Asia.

Countries engaged in regional cooperation (above all, Russia, China, and Kazakhstan) view Central Eurasia as an area of cooperation and harmony, rather than competition between development or economic models. In order to create favorable conditions for their growth and prosperity, all countries are ready to look for mutually acceptable compromises and respect each other’s interests in all areas of cooperation. Such negotiability is an important guarantee of international political stability in the region as the basis for long-term international cooperation.

Considering all these advantages, Central Eurasia can become a new center for attracting capital and investments and, in the geopolitical and geo-economic senses, a key element of Greater Eurasia that embraces the European Union, central Eurasia itself, East, Southeast and South Asia, and the Persian Gulf region.

AN AREA FOR JOINT DEVELOPMENT

The most promising and complementary interstate projects – Eurasian economic integration and large-scale partnership within the framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt – should become the main driving forces behind the transformation of Eurasia into a macro-region of joint development.

The Eurasian integration and its institutional shell – the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) which became operational on January 1, 2015 – will help work out a legal framework for a joint breakthrough and serve as an effective tool for preventing and resolving interstate disputes. In addition, the participation of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in the EEU creates a situation where China and the EU markets will be separated by only one customs border. A common customs and tariff space will give indisputable advantages to the Eurasian co-development project.

While the EEU creates legal conditions for building transport and logistics infrastructures and furthering joint development, the Belt project will impart enormous trading and investment momentum to these effrots. China’s experience in developing economic belts inside the country will be useful in creating new international and transcontinental economic areas which can link resources, production facilities and markets.

Considering the exceptional role of these two initiatives, the synergy of Russian and Chinese efforts towards the economic rise of the center of Eurasia will be a major factor contributing to the success of the Eurasian project. The experience of Russian-Chinese relations shows that Moscow and Beijing can cooperate in many areas by playing a positive-sum game.

Russia, which has entered a period of long-term deterioration of relations with the U.S. and its allies, now needs to create such opportunities for itself that would be least dependent on the West. Russia is interested in strengthening the Eurasian integration project, having more countries joining it, establishing regional development institutions to complement the existing international financial and economic bodies, and excluding military threats and challenges along its south-eastern perimeter, especially in Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Another major task is to step up efforts to enhance the economic and political role of Siberia and the Russian Far East, and to make the strategic partnership with China irreversible.

China is interested in gradually forming a system of international trading, economic and political interaction in Eurasia that would provide a transport corridor, relatively independent of traditional sea routes, between China and European markets. Beijing needs favorable political conditions for implementing its investment projects in Kazakhstan, Central Asia, Siberia, and the Russian Far East. It seeks to minimize risks and threats from Islamic extremism, and optimize efforts to develop its own western regions.

For the time being, external factors facilitate, rather than hinder, the implementation of the large-scale Eurasian co-development project. The pressure put on Russia by the West and on China by the East makes their cooperation the most rational strategy. China’s economic initiatives and Russia’s institutional and legal ones are different in nature and therefore complementary. Central Eurasian countries – Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Mongolia, as well as to some extent Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan – can ensure their international political role and socio-economic stability only by participating in major cross-border projects.

The transport and logistics potential of the region is enormous, and so is the co-development potential of Eurasian countries (the creation of cross-border investment clusters and areas of priority development). The Belt project will offer a shorter transportation route between Europe and Asia than that going via the Suez Canal. The new route will be 8,400 kilometers long, of which 3,400 km have already been built in China, and the remaining 2,800 km and 2,200 km are under construction or modernization in Kazakhstan and Russia, respectively.

The already operating section of this route from Western China to Western Europe passes via the cities of Lianyungang, Zhengzhou, Lanzhou, Urumqi, Khorgas, Almaty, Kyzylorda, Aktobe, Orenburg, Kazan, Nizhny Novgorod, Moscow, and St. Petersburg, and provides access to Baltic Sea ports. The bulk of the transit traffic goes via this route. Its major advantage is that it crosses only one customs border between China and Kazakhstan.

Redirecting the main trade flows to this route will significantly reduce costs and insurance expenses since this transport and logistics corridor is much safer and better protected from natural disasters and international political instability characteristic of the South Seas. Reorientation of a major part of Russian energy exports towards growing Asian markets will also increase returns on investments in related infrastructure projects.

RUSSIA’S EURASIAN STRATEGY

The importance of economic upsurge in the center of Eurasia is obvious to Russia, as it will bring both direct and indirect benefits to the state, businesses and the country as a whole.

Firstly, the development of the center of Eurasia holds much economic promise. On the one hand, it will unite the interests of the state and private businesses in developing Russian regions, and on the other hand, it will help create a long-term infrastructure for profitable operations of numerous private companies interested in production and trade cooperation with other countries in the region.

Secondly, an economically strong and investment-attractive center of Eurasia is a sine qua non (indispensable condition) for economic growth in Russian regions – Siberia and, to a certain extent, the Far East. For Siberia with enormous human and resource potential, participation in the Silk Road project will not only increase transit flows but will also help integrate its economy into the open international system.

Transit operations and extractive industries will be the main recipients of initial investments (from states and specialized financial institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Silk Road Fund, and others). At the next stage, investments will be made in processing and other industries, including high-tech ones. This stage will require active efforts to attract private investment that can produce a quick economic effect, using their high potential and low competition in the region. The creation of new transport routes is not at variance with Russia’s initiatives, such as the Northern Sea Route.

In terms of international politics, the project to develop the center of Eurasia will give Russia an important foothold in global affairs and facilitate its development and strengthening as an international center of power connected with other actors seeking to stabilize, rather than unsettle, the region. Stronger international cooperation around the center of Eurasia is concordant with Russia’s commitment to the development of the Eurasian Economic Union as a full-fledged interstate association with elements of supranational integration, and will resolve the problem of choice for many small countries in Eurasia.

In addition, as Russia increases its political power in the context of Central Eurasia’s economic development, many other countries looking for a place of their own in the world or not satisfied with their current position can be “turned” towards this ambitious Eurasian project. Moscow can offer advantageous cooperation in the project to countries in Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus (and to some other partners, such as Turkey and Mongolia). If the project succeeds and Central Eurasia embarks on accelerated economic development and multiplies its human resources, there may emerge a new Eurasian identity, which has been so much spoken and written about by Russian philosophers Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Georges Florovsky, and Pyotr Savitsky. In the 1920s, such identity seemed to be nothing more than speculation, but now it may acquire a real geopolitical and economic foundation.

Economic development of Central Eurasia, with Russia’s interests respected and potential tapped to the maximum extent possible, is the concern of not only the state but also of the business community. Encouraging private initiative and turning areas east of the Urals into a “Russian frontier” and a territory of unlimited possibilities should become an integral part of the process. If business and the state quickly work out a proper agenda, Russia has every chance to lead this growth with concentrated resource, production and intellectual flows.

A special place in the national strategy of Eurasian co-development should be given to efforts to tap the unique potential of Western Siberia, which is not only rich in natural resources but also has well-developed industrial facilities and enormous human capital. The development of both latitudinal and longitudinal transport routes within the framework of the large-scale Eurasian project will help to solve the problem of Siberia’s remoteness from external markets.

Big Siberian cities, above all Krasnoyarsk and Novosibirsk, have everything to become major Eurasian transport and logistics hubs and centers for regional development projects, including their technological, industrial, and educational components. Siberia’s water resources and agricultural lands have a great economic potential, too. Therefore, Russia’s Eurasian strategy, aimed at using its transit capabilities and ensuring stabilization and long-term development in the whole of Central Eurasia, should focus on the international positioning of Western Siberia and its leadership in a number of cross-border projects.

Another promising area of the project is a common electricity market. Its large size, the number of generating capacities and their interconnection can make this market highly efficient. In addition, nuclear power engineering coupled with hydroelectric power generation will secure stable electricity supply in Central Asia in winter and summer time. It may be advisable already now to consider extending the common electricity market to Western China with a population of 22 million. In the future, a ring power system may be built to cover Siberia, Kazakhstan, Central Asia, and western provinces of China.

In order not to miss the “Eurasian momentum,” Russia needs to discuss with its main regional partners, above all China, the new strategy of co-development in Eurasia. It is necessary to set up a high-level commission on cooperation for developing transport and logistics corridors in Eurasia and implementing co-development projects. The EEU needs to establish a working group on the transport/logistics, including air transport, infrastructure, which may include representatives of Kyrgyzstan, and the Eurasian Economic Commission should initiate an EEU transport and logistics strategy (White Paper) reflecting a common position of the participating countries. It is advisable to prepare a joint Russian-Kazakh-Chinese strategic document, entitled “The Energy Belt of Eurasia,” which would set long-term priorities for international cooperation in the field of energy trade, taking into account objective transformations in this market.

A new program, Central Eurasia Dialogue, would help create a political format for systemic dialogue among Eurasian integration institutions and regional partners (China and other countries that are not EEU members yet). It is time to work out at the expert and political levels a long-term program to strengthen other international cooperation institutions, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Collective Security Treaty Organization, in the new context of regional cooperation.

Experts and analysts should assess prospects for international cooperation on the river Irtysh, which is shared and actively used by China, Kazakhstan, and Russia, on the basis of the “common river” principle, similar to the Lower Mekong Initiative, including the creation of an effective basin commission and the attraction of a block investor.

While implementing co-development projects in Eurasia, Russia, China, Central Asian countries, Mongolia and eventually India, Turkey, Iran, and South Korea will find answers to many domestic and international challenges, lay the foundation for the region’s sustainable development and preclude its possible explosion from within. Central Eurasia must become a safe and sturdy home for its peoples and a smooth-running common backyard for Russia and China, so that they could address and solve their strategic foreign policy tasks.

The rise of Central Eurasia is one of the three components of Russia’s new global strategy. The other two are relations with Europe, a region closest to Russia civilizationally and an important source of technologies and social experience, and Russia’s current turn towards the Asia-Pacific region. Russia’s internal development should be meaningfully linked to its main foreign policy imperatives. This approach, along with efforts to modernize state governance, change the exhausted economic model, and build up military-political capabilities, will help strengthen Russia’s position as a 21st-century world power.