This article is a shortened version of the paper written for the Valdai International Discussion Club and published in April 2015. Full text is available at: http://valdaiclub.com/publication.

Political events in 2014 brought to the fore a more fundamental disagreement between Russia and the West about the European security architecture and the distribution of power in Russia’s neighborhood in general. Yet political implications are far broader, and likely to be felt for years, moving Russia closer to emerging powers such as China and India, but also to Brazil.

From Economics to politics

When Russia hosted the first BRIC Leaders’ Summit in June 2009, Russia’s President Dmitry Medvedev hailed Yekaterinburg as “the epicenter of world politics.” The need for major developing world nations to meet in new formats was “obvious,” he said.

The Western media reacted with a mix of neglect and rejection. As The Economist wrote at the time: “This disparate quartet signally failed to rival the Group of Eight industrial countries as a forum for economic discussion. … Instead, the really striking thing is that four countries first lumped together as a group by the chief economist of Goldman Sachs chose to convene at all, and in such a high-profile way.”

Those who took notice adopted a more critical stance and developed a narrative of the BRICs as potential “troublemakers.” A month prior to the BRICs Foreign Ministers’ meeting in Russia, Princeton professor Harold James predicted that “the BRICs will look for compensating power, and military and strategic influence and prestige, as a way to solve internal problems. Gone are the 1990s, when for a brief moment in the immediate aftermath of the end of the Cold War, the world looked as if it would be permanently peaceful and unconcerned with power. That hope soon proved illusory. Many commentators, indeed, were stunned by the rapidity with which tensions returned to the international system. While many blame U.S. behavior, these tensions have in fact been fueled by the unfolding of a new logic in international politics.”

Yet when looking at the BRICs’ behavior, it became clear that they were far more status-quo oriented than their rhetoric suggested. Calls for modifications of voting rights in the IMF, for example, were not meant to undermine Bretton Woods institutions – quite to the contrary, BRICS have been instrumental in the process of keeping them alive. Brazil’s former President Lula routinely demonized the IMF, but also decided to strengthen the institution by lending money to it. Much rather than soft balancing, emerging powers at the time seemed to be “soft-bandwagoning:” they did not want to rock the boat, just make it a bit wider and more democratic.

As Medvedev pointed out at the 2009 summit, there was a “need to put in place a fairer decision-making process regarding the economic, foreign-policy and security issues on the international agenda” and that “the BRIC summit aims to create the conditions for this new order.” Particular emphasis was laid on ending the informal agreement that the United States and Europe could appoint the World Bank President and IMF Director, respectively. Rather, those leadership positions should be appointed through “an open, transparent, and merit-based selection process.” This affirmation became somewhat of a rallying cry for the BRIC nations in the following years, thus creating a clear and simple narrative that all emerging powers could agree on.

President Lula argued on the day of the summit: “We stand out because in recent years our four economies have shown robust growth. Trade between us has risen 500 percent since 2003. This helps explain why we now generate 65 percent of world growth, which makes us the main hope for a swift recovery from global recession. BRIC countries are playing an increasingly prominent role in international affairs, and are showing their readiness to assume responsibilities in proportion to their standing in the modern world.”

A show of confidence and the projection of stability were particularly important at a time of global economic chaos, when the BRIC countries perceived a leadership vacuum. BRIC nations enjoyed an average annual economic growth of 10.7 percent from 2006 to 2008, strongly exceeding growth figures in the developed world. As a consequence, one of the main themes of the summit was how to create a new world order less dependent on the West.

Back then, even more benign observers would hardly have predicted that the BRIC grouping would turn into the most prominent political platform outside of the West. In late 2010, South Africa was invited to join the group, a move that strengthened the group’s global visibility and legitimacy to speak for the emerging world, while not reducing its capacity to develop joint positions. Quite to the contrary, the first BRICS summit with South Africa’s participation in 2011 seemed to go further than the previous two summit declarations in 2009 and 2010. In 2014, the grouping set up a Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) and a set up a development bank, scheduled to begin operating in 2016.

Equally surprising to many, the grouping reached unprecedented political visibility when, in a joint communiqué, BRICS representatives rejected calls to exclude Russia from the G20 in the aftermath of the Crimea crisis, thus decisively undermining Western attempts to isolate Russia. In the Hague in late March 2014, the BRICS foreign ministers opposed restrictions on the participation of Russian president Vladimir Putin in the G20 Summit in Australia in November 2014. In their joint declaration, the BRICS countries expressed “concern” over Australian foreign minister Julie Bishop’s comment that Putin could be barred from attending the summit. “The custodianship of the G20 belongs to all member-states equally and no one member-state can unilaterally determine its nature and character,” the BRICS countries said in a statement.” Similarly, Brazil, India and China abstained from a UN General Assembly resolution that directly condemned Russia’s Ukraine policy, thus markedly reducing the effectiveness of Western attempts to isolate President Putin. Finally, no BRICS policymaker has criticized Russia in the aftermath of the intervention in Crimea – their official responses merely called for a peaceful resolution of the situation. The final document of the BRICS meeting stated that “the escalation of hostile language, sanctions and counter-sanctions, and force does not contribute to a sustainable and peaceful solution, according to international law, including the principles and purposes of the United Nations Charter.” Furthermore, China, Brazil, India and South Africa (along with 54 other nations) abstained from the UN General Assembly resolution criticizing the Crimea referendum.

As Zachary Keck noted, the BRICS countries’ support for Russia was “entirely predictable,” even though the group has always been constrained by the differences that exist between its members, as well as the “general lack of shared purpose” among such different and geographically dispersed nations. “BRICS has often tried to overcome these internal challenges by unifying behind an anti-Western or at least post-Western position. In that sense, it’s no surprise that the group opposed Western attempts to isolate one of its own members.”

Perhaps in the most pro-Russia statement of any BRICS member, India’s National Security Adviser Shivshankar spoke of Russia’s “legitimate interests” in Crimea, in what became the most pro-Russian comments made by a leading policy maker of a major power. India made clear that it will not support any “unilateral measures” against Russia, its major arms supplier, pointing out that it believes in Russia’s important role when dealing with challenges in Afghanistan, Iran and Syria. India’s unwillingness to criticize Russia may also stem from a deep skepticism of the West’s tacit support for several attempted coups against democratically elected governments over the past years – for example in Venezuela in 2002, in Egypt in 2013, and now in Ukraine.

This behavior has surprised many Western observers, leading some to expect the emergence of a world order marked by a profound division between the G7 and BRICS. Indeed, while Russia’s ties to BRICS are likely to grow stronger, attempts to improve ties between Russia and the West will be hampered by the fact that the current state of affairs is not the product of short-term animosities or problem about a particular policy issue, but a more fundamental disagreement about the European security architecture and the distribution of power in Russia’s neighborhood in general. Unless Russia’s leader fears that his country could implode economically, chances for a meaningful reset are slim, and even in case of a Russian collapse a rapprochement would be far from guaranteed. Even if a peace deal is reached soon between Ukraine and the rebels, deep-seated distrust will remain for years to come. That will turn the BRICS countries into key allies for Moscow, indispensable for keeping Russia economically and diplomatically connected to the rest of the world.

Dialectics of the relations with the West

Yet reality is likely to be far more complex, largely because the two groupings are less cohesive than many would suggest. While the G7 has been relatively united in its response to Russia so far, European powers may not follow the United States in applying long-term sanctions, largely because their economies are far more interconnected with Russia. The G7 also differs on many other broad questions, such as how to deal with the conflict between Israel and Palestine, how to reform the UN Security Council, or, in 2011, how to deal with the situation in Libya. In today’s more multipolar scenario, the G7 is far weaker than it used to be two decades ago, when its agenda-setting capacity was truly impressive: There was no non-Western pole capable of determining the global discourse. Today, by contrast, no major global challenge can effectively dealt with by the West alone.

In the same way, merely pointing out that BRICS refused to criticize Russia during the Crimean crisis does not take into consideration that they, too, differ on many broad issues that limits their capacity to take a joint position on many problems. For example, despite yearly meetings by each BRICS country’s National Security Advisors, BRICS have not deepened their military cooperation or organized any joint military exercises, such as IBSA (India, Brazil, and South Africa). Neither Russia nor China have explicitly supported India’s or Brazil’s ambition to join the UN Security Council, and in the possibility of a more direct confrontation between Russia and West, none of the BRICS countries will explicitly support Moscow.

In order to properly understand the BRICS’ refusal to criticize Moscow – thus protecting Vladimir Putin from international isolation – one must take the overall geopolitical context into consideration. The BRICS’ unwillingness to denounce and isolate Russia may have less to do with its opinion on Russia’s intervention in Crimea per se and more to do with its skepticism of the West’s belief that sanctions are an adequate way to punish whom it sees as international misfits. All BRICS countries have traditionally been opposed to sanctions and have often spoken out against the U.S. economic embargo against Cuba. In the same way, they have all been wary of implementing the most drastic economic sanctions against Iran. What is often forgotten is that the U.S. Congress imposed sanctions on Brazil as recently as the 1980s, when the latter pursued nuclear enrichment and reprocessing technology. India also suffered from international isolation after its nuclear tests, and China feels often threatened by U.S. rhetoric. From BRICS’ perspective, pushing countries against the wall is rarely the most constructive approach.

Furthermore, even though it is unclear whether Western influence contributed to the anti-Yanukovich riots in Kiev prior to Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the episode did evoke memories of the West’s highly selective support of demonstrations and coup d’états in other countries. Western leaders often criticize the BRICS for being soft on dictators, calling the country an irresponsible stakeholder that is unwilling to step up to the plate when democracy or human rights are under threat. Yet despite its principled rhetoric, the West, observers in Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa remember, was quick to embrace illegitimate post-coup leaders in Venezuela (2002), Honduras (2009) and Egypt (2013), and actively support repressive governments when they used force against protest movements, e.g. in Bahrain. Criticizing Russia in this context would have implied support for the West and its possible engagement with Kiev.

When seeking to understand BRICS’ position, one must also consider their more general critique of the apparent contradictions of the global order. Why, they ask, did nobody propose excluding the U.S. from the G8 in 2003 when it knowingly violated international law by invading Iraq, even attempting to deceive its allies with false evidence of the presence of weapons of mass destruction in the country? Why is Iran an international pariah, while Israel’s nuclear weapons are quietly tolerated? Why did the U.S. recognize India’s nuclear program, even though Delhi has never signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty? Why are systematic human rights abuses and a lack of democratic legitimacy in countries supportive of the U.S. acceptable, but not in others? Commentators in the BRICS countries have argued that these inconsistencies and double standards are in their totality far more damaging to international order than any Russian policy. Especially for voices more critical of the U.S., the West’s alarm over Crimea is merely proof that established powers still consider themselves to be the ultimate arbiters of international norms, unaware of their own hypocrisy. If asked which country was the greatest threat to international stability, most BRICS foreign policymakers and observers would not name Russia, Iran and North Korea, but the United States.

This matters because Russia’s annexation of Crimea took place at a time when anti-Americanism around the world still runs high as a consequence of the NSA spying scandals, making aligning with U.S. positions politically costly at home. This was particularly the case in Brazil, where the U.S. decision to spy on President Rousseff, but even more so on Petrobras, seemed to confirm suspicions that U.S. policymakers would support international rules and norms, yet were unwilling to fully adhere to them.

More indirectly, BRICS’ stance on recent events in Ukraine is part of a hedging strategy by rising powers that are keen to preserve ties to the U.S., but are also acutely aware that the global order is moving towards a more complex type of multipolarity, making it necessary to maintain constructive ties with all poles of power. While BRICS are willing to protect Russia to some degree, their capacity to go along with Moscow is conditioned by their conviction that doing so does not hurt their ties to the West. The BRICS countries will therefore shy away from any moves that may change that calculation.

The G7 ever unified?

The G7 may emerge stronger and more unified from last year’s political developments. The situation is also likely to strengthen intra-Western coherence and resilience in general, symbolized by the G7 summit that will take place for the second time without Russian participation in 2015, in Elmau, Germany. There, Angela Merkel, a key actor in the West’s response to Russian foreign policy, will seek to strengthen macroeconomic policy coordination between its members, aside from proposing common responses on issues like global pandemics and energy security. Despite its incapacity to fix global challenges on its own, the forum’s continued existence and importance underlines that Western like-mindedness on some issues can still go a long way. Despite the clear limitations mentioned above, the G7 is still influential when acting together, and it remains a grouping to be reckoned with for years to come, even if its share of global GDP is bound to decline over the coming years.

Growth figures in the BRICS countries in 2015 will be far lower than they were in 2009, and the United States is already growing faster than Brazil, Russia and South Africa. In that sense, seen from Brasília, Pretoria and Moscow, the global environment offers fewer opportunities than a few years back, when established actors and institutions faced a severe legitimacy crisis and when emerging powers saved the global economy from a complete meltdown. Yet it would be wrong to expect the BRICS grouping to weaken in the coming years. The reelection of Dilma Rousseff in Brazil has been hailed in the Russian and Indian media as crucial in maintaining momentum in the slow process of BRICS institutionalization. Indeed, it is unclear to what extent a President Aécio Neves – Rousseff’s major rival – would have continued Brazil’s support for initiatives such as the BRICS Development Bank, which some see as a rival to existing Western-led institutions.

The underlying principle still holds: Being part of the BRICS grouping generates tangible benefits but virtually no cost. And yet, the 7th BRICS Summit may put that logic to its greatest test so far. Increasingly anti-Western, Russia will propose a series of measures during the summit discussions that are likely to generate strong criticism in the West, such as arguing for the UN’s International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to replace the U.S. government as the ICANN overseer. While China is supportive of the idea, Brazil is unlikely to go along, considering its leadership on the matter at the 2014 NetMundial in São Paulo.

In several other areas, Russia may seek to politicize the BRICS meeting further and use it as an anti-Western platform, particularly if current sanctions are still in place next year. That strategy will cause resistance among the other members that have no interest in unnecessarily antagonizing Washington, DC. In fact, Brazilian foreign policy makers will be careful not to admit any overly strongly-worded language in the final summit declaration that may imperil a key goal for Brasília in 2015: repairing frayed ties with the United States.

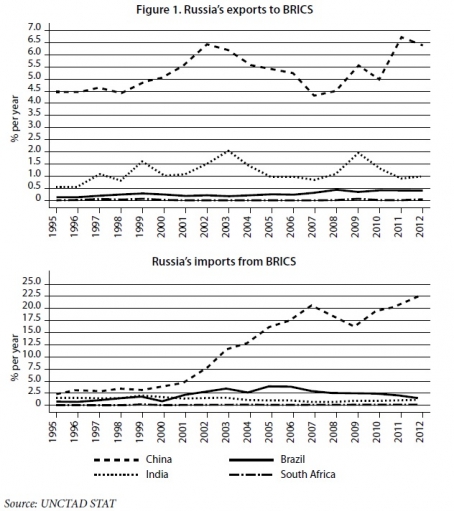

That is why, even in the case of long-term estrangement between Russia and the West, we are unlikely to see a Cold War-scenario in which all key actors are taking clear sides. A brief look at intra-BRICS trade makes clear that even for Russia, wholly depending on the BRICS countries is hardly possible.

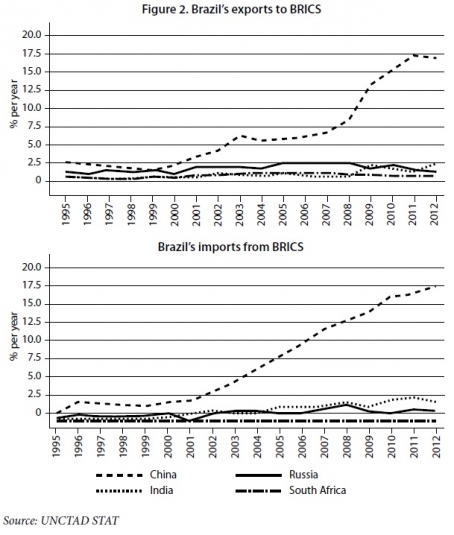

The same is true when analyzing, for example, Brazil’s trade data:

Indeed, while China is Brazil’s most important trading partner since 2009, the importance of the other BRICS countries for the Brazilian economy is extremely small. Both the United States and Europe remain of great economic importance to Brazil – as they do for all BRICS countries, Russia included, so no BRICS member will go along with any proposals that may inflict on them the same economic sanctions the West has imposed on Russia. It is equally telling that while the G7 has achieved a moderate degree of cohesiveness regarding sanctions against Russia, policy makers in Moscow were well aware of the fact that they would not be able to convince their fellow BRICS countries to join Russia in applying counter sanctions.

Despite all that, the BRICS Summit will remain a key element of the global governance landscape, contrary to the common practice in the United States and Europe to dismiss the grouping as odd or unimportant. Even without imposing his internet-related views on the other BRICS countries, the summit will be a success for Vladimir Putin. Within a few days, the Russian president will host not only the BRICS leaders, but also heads of state of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). One year after the Winter Olympics, Russia will continue to successfully resist Western attempts to turn it into a pariah. At the same time, during the 7th BRICS Summit policy makers may release some news about the creation of the BRICS Development Bank, which is expected to start operating in 2016.