Mega-scenarios for world development in the 21st century are not terribly diverse. The first among them, held to be the mainstream in present-day political thought, is reduced to forecasting American domination for the foreseeable future. U.S. preponderance over all other powers, certainly as concerns the main components of might, is unprecedented. The United States can cope with anything. Arguments to prove American omnipotence become even more convincing when presented with the kind of emotion that always underlies lofty patriotic upsurges, like the one that has swept the United States following the 9/11 tragedy.

In American political quarters any other country is usually discussed not so much from the point of view of potential cooperation, as with regard to its ability to challenge the U.S. might or to throw doubt upon the possibility of unilateral action. The rest of the world has perceived the concept of U.S. hegemony as something quite convincing, though not always as a reason for elation.

It is, in many ways, within this framework that the second scenario emerged; a scenario that is associated with anticipation of chaos in international relations and one which has become especially widespread among the left and anti-globalist circles. Humankind is facing the prospect of environmental calamities, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and a deadly clash of civilizations, of the North and the South. But there will be no one to grapple with these global challenges, for the only superpower that can provide world leadership will be preoccupied with its own egotistic interests that will have little or nothing in common with those of the rest of mankind.

James Gillray, «The Plumb-Pudding in Danger or State Epicures Taking un Petit Souper», 1805. http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/367748

It would seem, however, that there is a third scenario in prospect, too. The world is moving, and will keep moving, towards greater consolidation and governability, rather than increasing unilateral trends and chaos. That is, to the rather forgotten Concert of Powers that provided a century-long peace for Europe from 1815 to 1914.

It will be recalled that the European Concert (let me call it the First Concert here) was born of joint efforts of Russia and

Great Britain. Russian Tsar Alexander I, in a benevolent move, suggested that the use of force should be relinquished and any conflicts arising should be resolved through arbitration by the great powers. The British Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, however, transformed the idea of the Russian Emperor into a more pragmatic concept based on a balance of power. At the Congress of Vienna, following the downfall of Napoleon’s empire, a sort of diplomatic oligarchy of the victorious powers emerged, in which Russia, Britain, Austria, and Prussia undertook to pool their efforts to maintain international stability and status quo. With France soon returning to the “European club” (it was France that was the target when the Concert was formed), the quartet turned into a “pentarchy,” and, with accession of the Kingdom of Italy, into a “hexarchy,” “the big six” (G-6) of the time. In the late 19th century, French historian Antoine Debidour described the Concert of the period as follows: “These states have not always lived in full accord. Bitter conflicts have erupted at times between some of them. Some of these states gained in strength and acquired greater influence than before, while others suffered a decline in one way or another and lost their former authority. But not one of them lost its strength to such an extent that the others could destroy it or expel it from the community. All of them continue to exist, time and again ensuring tranquility, equally, by their rivalry and their accord.” In the period of the First Concert, the main strategies of the victor countries were cooperation in the area of security and economic engagement.

In my opinion, today, in the conditions of globalization, the Concert will be performed on the global stage with the participation, at least, of the U.S., Europe, Russia, Japan, India, most probably China, and some other countries.

Naturally, this assumption will evoke plenty of criticisms, chiefly associated with the fact that the First Concert was built on a balance of power. There can hardly be any talk of balance in a situation where, as they say, “the United States has no rival in any critical dimension of power. There has never been a system of sovereign states that contained one state with this degree of dominance.” How can powers with different clout get along in a Concert? And what can Russia, weakened and thrown back to its boundaries of the 16th century, have to do with a Concert?

Meanwhile, there are reasons to believe that the creation of a new world has already started. First: Although America is the only superpower today a certain balance of power, does exist in the world. The U.S. is not capable of exercising global regulation unilaterally and will de facto be moving towards more cooperative approaches.

Second: Russia, discarded by many today, remains an important factor in the world system, and can and will, therefore, play a significant and independent role in it.

Third: Conditions for a “century-long peace” among great powers are in no way worse than they were in Europe in the 19th century. And the world has already started its long-term movement towards a Global Concert, the composition and format of which are yet to be identified.

THE U.S., THE SOLE SUPERPOWER, BUT NOT THE ONLY POWER

A factor of great for a hegemonic power is, of course, its economic resources. As a result of the economic boom of the 1990s, the U.S. has increased its share in the world economy to 30 percent. This is a very big share. But it is less impressive if calculated using a more concrete indicator—purchasing power parity, which is put at 21 percent. To be sure, there were countries in world history with a higher or comparable level. In the mid18th century, China accounted for 32.8 percent of the world output, and India within its boundaries of the time (that is, together with Pakistan), for 24.5 percent. Britain held leadership, with 22.9 percent, in 1880, and the United States had moved to first place, with 23.6 percent, by 1900. It is not there today any more, but right after World War II the United States reached its high point in terms of economic power (up to 40 percent) in relation to other countries. Today, apart from America, there are other major economic players in the world. The European Union has almost caught up with the U.S. in aggregate GDP, while some of the EU countries are ahead of America in standards of living. No doubt, after the EU expansion to Central and Eastern European countries, the Union will move to the fore. China’s GDP has trebled in the past 20 years and continues to grow at a rate of 10 percent, surpassing Japan. Fast growth has also resumed in post-Soviet countries.

Meanwhile, the situation in the American economy is not very impressive. Continual prosperity has not materialized. Over the past decade, American society has been consuming too much, importing and borrowing too much, and saving too little. Within the two-and-a-half years of stock exchange crises, recessions, and unprecedented corporate scandals and bankruptcies, the U.S. stock markets have lost up to $7 trillion in capital drain. Foreign investments in the U.S. economy in the second quarter of 2002 fell to an all-time low since 1995. When in New York, in July 2002, after a long interval, they switched on the clock recording the size of American public debts, it showed a sum of $6.1 trillion and it kept growing at a rate of $30 a second. The dollar is experiencing bouts of fever, and its exchange rate depends on joint currency interventions by the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan. Needless to say, no economic difficulties have ever (at least in the post-World War II period) forced the U.S. to give up any of its principal foreign policy plans. But it is equally clear that the U.S. share in the world economy will be shrinking rather than growing.

America’s military power is unprecedented. Possessing, as it does, a giant striking force and unparalleled target precision, it has no equals either at sea, in the air, or in space. But the American land forces (1,384,000 men) are not the most numerous. They are noticeably smaller than those of China (2,470,000) or the aggregate European forces, and only a little bigger than those of India (1,303,000), North Korea (1,082,000), and Russia (1,004,000). In the nuclear arms component, the U.S., at least quantitatively (with tactical nuclear warheads counted), is lagging behind Russia. It is quite possible that European defense and security policy plans, which at present are viewed with a grain of salt, may develop into something more serious. This is quite probable considering the return of the European Union’s main driving force, Germany, to the international military arena in Kosovo and Afghanistan.

But even dominant defense might does not ensure quick achievement of desired political and military results. Can Desert Storm be really considered that victorious if a new tornado threatens to break out a decade later? After Kosovo, one of the leading Republican Congressmen inquired, “If this is victory, then what in this case is defeat?” It was Russia (and Victor Chernomyrdin personally) that relieved the U.S. and NATO of the deadlocked Yugoslav situation, which put into question the ability of the superpower and the alliance it led to act as the sole European arbiter. After the quick victory over the Taliban and Al-Qaeda in Eastern Afghanistan came a long period of hostilities in other parts of the country, the terrorists’ flight into Pakistan, the shaky position of the central and local Afghan authorities, an upswing in drug trafficking, mass migration, and humanitarian catastrophe. Meanwhile, bin Laden is apparently alive. On top of this, in order to achieve military success, the U.S. should commit its land forces (something it avoids doing for fear of heavy casualties). The U.S. should also be prepared to assume responsibility for reconstructing the country. However, the money to help Yugoslavia and Afghanistan is allocated chiefly by other countries.

America’s military superiority today is akin to that of Britain’s in the 19th century. Britain at that time dominated the seas (the then sea, air and space) but was weak on the ground, feared “mass retaliation” by any other great power, and cared for its own financial interests. This, however, was no handicap for Britain to play solo in the First Concert.

A hegemonic power that does not want to be at war with all and everyone has to bribe, persuade, and use financial, diplomatic and other means. The U.S., however, has for many years delayed its payments to international organizations. America is at the bottom of the OECD list of states allocating resources, in terms of per capita of population, in aid to developing countries (and most of this money is sent directly to the Middle East). In the 1990s, the U.S. was closing its embassies and consulates in many countries. The sole superpower proved unable to prevent the emergence of two new nuclear powers, India and Pakistan. It lacks the resources to bring peace between Israelis and Palestinians, or to protect its own territory from attacks, the most destructive in the whole U.S. history.

Aspiration for world hegemony in the U.S. today is stronger than ever. America has changed considerably, but not enough to be able to change its own nature. It was and remains a rather self-centered country, not particularly outward looking to the world around. American political culture has a considerable isolationist stratum within it. This society can hardly maintain for a long time, for decades, an internationalist spirit that is not inherent in it. A new 9/11 would be required to keep up the fighting morale in the U.S. Public opinion would not go along with a unilateral drive. In September 2002, 64 percent of Americans supported efforts to oust Saddam Hussein, but only 30 percent favored going into Iraq without allies. Besides, it should be kept in mind that the American two-party system is a real factor. As long as the inertia of “rallying around the flag” keeps its momentum and George Bush’s popularity ratings hit their highest points ever, the Democrats can tone down their opposition, but this situation cannot last indefinitely.

The strategy of world hegemony implies performing the role of not only world policeman, but also world manager. However, the essence of the present-day U.S. policy does not envisage responsibility for global management. It is designed to ensure its own freedom of action, freedom from responsibility for anything that represents no immediate interest from the point of view of security or electoral support. But most of the world problems have no connection to any direct threats to U.S. security or interests of the American electorate. The concept of “humanitarian intervention” has and will be applied selectively: not where the worst violations of human rights occur, but in the regions where the U.S. has some other interests at stake. America’s aspiration is not so much to be the orchestra conductor as to ensure the opportunity for solo parts.

As for the role of the U.S. as a moral leader, this is something that has obviously not shown any progress recently. “The leader loses in aspirations for moral superiority if he ignores major international agreements,” and this is often the case with the United States. Amnesty International last year noted that the U.S. topped the list “of the greatest disappointments in human rights in the past 40 years.” That same year, the U.S. lost its seat in the UN Human Rights Commission. Furthermore, domestic security measures taken in the past months by America have raised numerous doubts.

America’s information domination is vast, but an interesting paradox arises amidst conditions where information flows are increasing exponentially. With information overflowing, perception is blunted. English is increasingly becoming the lingua franca of the power elite today, but remains only a second most spoken language in the world, with three times fewer people using it (479 million) than Chinese (1.2 billion). Some time in the future, it may even become a third most spoken language, since the number of those speaking Hindi is growing rapidly (437 million in 2001). And it is by no means certain that it is the American lifestyle that is winning over the world and not European.

The present strategy of the American leadership renders doubtful the U.S. ability to lead even its allies. The United States and Europe cannot reach consensus on a number of issues. The U.S. has not signed or has not ratified such documents as the Kyoto Protocol or agreements to ban nuclear testing, biological weapons and anti-personnel mines. There is no unity in views on the National Anti-Ballistic Defense and the Middle East. The U.S. and Europe have differences in assessing such issues as Afghan POWs in Guantanamo, the International Criminal Court, and death penalty. There are also differences in the areas of trade, European defense and security policies, and Iraq. All of a sudden, anti-American sentiments have intensified in Japan. It looks like contradictions between the U.S. and its closest allies today are no less profound than between the U.S. and Russia, India and even China. This, apart from everything else, indicates a possibility that allied and bloc systems may not necessarily become a really serious impediment to a Concert. There is an understanding in the United States that unilateral actions may be detrimental to the country’s own interests. Joseph Nye, in his book on the subject, The Paradox of American Power, regarded almost as a classic, justly noted, “The danger posed by the outright champions of hegemony is that their foreign policy is all accelerator and no brakes. Their focus on unipolarity and hegemony exaggerates the degree to which the United States is able to get the outcomes it wants in a changing world.” There is also an understanding based on historical experience that overloading and overexpansion of an empire may lead to internal anemia, to creation of “turbulent frontiers,” “self-encirclement,” and demise from “its own hubris.”

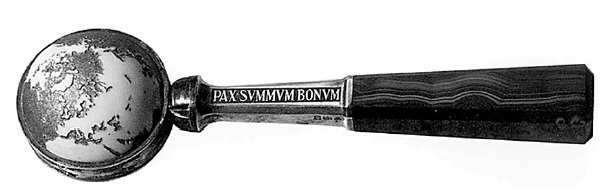

“Peace Is the Supreme Good” The chairman’s gavel at the disarmament conference in Geneva, 1932-1935

For all the obvious indications of a unilateralist trend in the Bush Administration’s rhetoric and actions, there are quite concert-inclined elements discernible in the U.S. policies. For the first time in many years, the U.S. has fulfilled its obligations to the UN and repaid all its debts. Eighteen years after America left UNESCO, President Bush announced the resumption of membership. Anti-Chinese sentiment has noticeably cooled off in Washington. Positive revolutionary changes have occurred in Russian-American relations. The United States has for the first time recognized the Palestinians’ right to their own independent state, much to the satisfaction of Europeans. In the run-up to the G8 summit in Kananaskis, the Bush Administration lifted anti-dumping duties from 116 metal products that are mostly manufactured in the European Union. Contrary to its earlier intention, the U.S. did not withdraw from the international peacekeeping force in the Balkans and agreed to a certain compromise regarding the International Criminal Court. The United States no longer sponsors Al-Qaeda, no longer helps the Taliban, no longer considers the Chechen terrorists freedom fighters, and does not provide arms for the Kosovo Liberation Army. The very nature of the newly emerging threats to America’s security, coupled with scandals flaring up around major corporations, has required a new portion of government regulation that subverts the libertarian “Washington consensus,” the cause of allergy in many countries with a greater degree of regulation and social orientation of the economy.

The United States is probably not the worst example among major countries which Charles de Gaulle once called “egotistic monsters.” It would be interesting to see how other nations would behave if they were as powerful as America is today.

America is the sole superpower, but not the only power. It cannot cope with everything, the less so with all at once. There is no balance of power in the modern international system. Henry Kissinger wrote in his Diplomacy, “Of course, in the end a balance of power always comes about de facto when several states interact. The question is whether the maintenance of the international system can turn into a conscious design, or whether it will grow out of a series of tests of strength.” A concert in which one of the instruments is louder than the others is quite possible. At the time of the Congress of Vienna, Russia was Europe’s military superpower: in Debidour’s words, “Alexander I was at that time all-powerful.” The European Concert survived quite successfully throughout the 19th century, with Britain’s overwhelming superiority in most components of strength. Moreover, as follows from the theory of hegemonic stability, developed above all by Robert O. Keohane, the international system may only function efficiently if it is maintained in workable condition by hegemonic powers. At the same time, in Keohane’s opinion, domination by one great power was neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for preserving international stability.

A Global Concert is in the interests of the U.S. itself. It provides the right to be heard and a sense of protection for other countries, which means it makes it possible to regard America not as a threat to stability, but as guarantor of the world order.

RUSSIA AS INDISPENSABLE POWER

Russia paid a high price for stopping the Cold War, pulling down the Berlin Wall, and stepping down from the imperial plane. We have received economic catastrophe and, instead of assistance as had been expected, condescending smiles from the “victors.” The attitude of the West towards Russia was rather in the manner of that of the victorious great powers towards post-Napoleonic France. As Talleyrand wrote, “The Allies wished to leave France with only a passive role; it had to be not so much a participant in events as a mere spectator. The fear of it had not yet disappeared, its strength was still causing alarm, and they all hoped to achieve security only if Europe would be incorporated in a system directed solely against France.” In the 1990s, the West went about arranging and expanding its system acting

mainly either in disregard of Russia or against its interests. And Russia, following the euphoria caused by the prospects of cooperation with the West, started, from the mid-decade, paying back in kind. But this happened not out of any inexhaustible “imperial nostalgia,” as Zbigniew Brzezinski would have it, but due to the impression, not quite unfounded, that the motive force of the West’s policy was doctrinal Russophobia, a desire to encircle and isolate Russia. There have been ample indications of this, from expansion of NATO to the bombing of Yugoslavia in spite of Russia’s desperate protests. Besides, the Russians themselves throughout the past decade indulged in self-humiliation, became all nostalgic about the country lost, and exaggerated the weaknesses of the country newly acquired.

Russia is not the USSR. It is smaller and weaker in many ways. But it still retains its positions, and is even strengthening them in some areas.

Disintegration of the USSR set in motion a process that led to the formation of nation-states, which has obviously been underrated in the West. Never before 1991, had there been on this planet such ethnically based sovereign countries as Ukraine, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenia, and the Russian Federation. Always a multiethnic community (or empire, whichever you prefer), Russia (the USSR) was a country where Russians were the lesser part of the population, and which was governed mostly by non-Russians (the Romanov dynasty, starting with Catherine II, was essentially of German descent, Stalin was a Georgian, and Khrushchev and Brezhnev came from Ukraine). Now, for the first time, the Russians constitute not just the majority, but the overwhelming majority (up to 85 percent) of the population. This phenomenon has required not only a painful (and yet to be completed) quest for national identity, but also set the stage for the formation of a qualitatively new national consciousness. The resulting growth in national awareness may consolidate society more strongly than the Communist dogma or the old formula “Autocracy, Orthodoxy, and Nationality” used in Russia under the tsars.

Russia does not occupy one-sixth of the world’s land mass, as the USSR did, but even with its one-eighth share it remains the world’s largest country. Population-wise, it occupies sixth place on the planet (145 million), and the Russian language is fifth in terms of the number of people speaking it (284 million). Russia’s cultural, economic and political influence are factors to contend with across the post-Soviet space. Russia is not one of the two superpowers. But it has retained the status of one of the great powers, a permanent member of the UN Security Council with the right of veto, and acts decisively in legitimizing actions to be taken by the world community or individual countries.

The situation in Russia’s economy is far from perfect, but in recent years its rate of growth has been clearly higher than the world’s average. In five years, according to estimates by the Brunswick UBS Warburg’s directors, labor productivity in Russia has increased by 38 percent, while America’s 13 percent, by comparison, looks rather unimpressive. The GDP, which is mainly estimated according to the ruble/dollar exchange rate and therefore looks comparable to that of the Netherlands, when calculated by the parity purchasing capacity of the ruble, amounted to $1,085 billion for the year 2000. This brings Russia to ninth place in the world, ahead of Brazil and Canada. The forecasts are that by the size of its economy in 2015, Russia will outstrip Britain, Italy, and France, and move to sixth place in the world.

In Soviet times, not one of this country’s enterprises featured on the Fortune-500 list of the world’s largest companies. There are several of them on this list today, even though the capitalization level of all Russian companies is underrated. In the Soviet period, the country’s foreign debt was growing, while in 2001 alone it went down by $13.2 billion and now amounts to a comfortably payable sum of $130.1 billion. Russia has noticeably improved its credit history. The USSR was importing grain, while the Russian Federation this year has exported grain to Brazil, Germany, Canada, and Bulgaria. The market environment, even if imperfect, does work.

Russia possesses the world’s largest mineral resources and is a major player on the world energy market. In 2001-2002 (April to April), Russia produced 15 percent of all crude oil coming from exporting countries, falling only a little behind Saudi Arabia (16.1 percent) and twice the level of third-placed Iran (7.4 percent). With exports of natural gas added, Russia has become the largest supplier of energy resources in the world. On top of this, it is the only country that can play on the side of OPEC or against it, participating officially at conferences of both exporters and consumers of liquid fuel (G8), and playing the role of “petroleum referee.” The West is increasingly conscious that Russia is a lot more stable and reliable partner in energy matters than Arab producers. And after the U.S. refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, it now depends on Russia whether this document will come into force.

Russia retains a vast, even though largely residual, military potential. Russia is a nuclear superpower, one of the two countries that can blow up the whole world in a twinkling. Throughout recent years, the Russian Federation has been the world’s second largest arms exporter and the main supplier of modern arms to two great powers, China and India. Russia’s stocks of tanks and armored vehicles are considerably greater than those of the U.S. In the components of military power where America dominates, air force, navy and space, Russia is in second place. Former Soviet superiority in space is a thing of the past, but even so, there are 43 Russian military satellites in space today. This is more than the total number of satellites orbited in history by any one country, except for the U.S. and also Japan (72 space satellites). The international space station built and maintained with Russia’s most active participation represents a good symbol of Concert.

It transpired at the turn of the century that the resolution of a whole number of regional problems depends on Russia. By way of trial and error, the West has already established that democratization in Belarus or stabilization of the situation in Central Asia and the South Caucasus cannot be achieved without Russia, the less so contrary to its interests. The transport lines in Eurasia in one way or another depend on Russia. Incessant attempts to create alternative channels, bypassing Russia, to transport energy resources in actual fact reflect Russia’s already existing decisive role in this area. Russia is a most important element in the European security system, which is emphasized by the special format of the Russia-EU and Russia-NATO relationships. Russia is regarded as the only “fair broker” in inter-Korean relations, and any resumption of North-South dialogue or the launching of economic reforms in North Korea would hardly be possible without Russia’s efforts.

Moscow’s role is just as unique in the Middle East, where it enjoys the trust of both the old friends, the Palestinians, and the new ones, the Israelis. The obvious improvement of Russian-Israeli relations has changed the nature of Russia’s ties with the West. The Jewish lobby in Washington, once traditionally harshly anti-Russian, is now pressing for repeal of the Jackson-Vanik Amendment and defends Moscow’s policy in Chechnya. For its part, Russia takes a more pro-Israeli stance than the European Union or even the U.S.

Russia plays a paramount role in the world community. At the same time, it is objectively destined to come out as an independent player, a separate center of power not to be disregarded in any international amalgamations. In the foreseeable future Russia will not be integrated in the main Euro-Atlantic structures, while in Asia it simply has nowhere to integrate. Unlike numerous countries, the Russian Federation will preserve its sovereignty. And, even if by virtue of its geographic situation, it is destined to be a global player.

The tendency to treat Russia as a defeated third-rate country began to subside already before the 9/11 tragedy. And after that day, the feeling has been growing stronger in the West that Russia is in many respects an “indispensable power.” Thomas E. Graham, chief expert on Russia in the U.S. National Security Council, points out that “ignoring Russia is not a viable option. Even in its much reduced circumstances, Russia remains critical to the United States’ own security and prosperity and will continue to do so well into the future.” Moscow has proved to be a highly valuable participant in the anti-terrorist coalition. Its stakes and experience in the region of Afghanistan are greater than anyone else’s, and it rendered substantial help to the U.S., supplying intelligence information and arranging air passages for U.S. combat aircraft and access to bases in the former Soviet republics.

A number of U.S. foreign policy priorities have been revised, which set off what I would call a revolution in Russian-American relations. Andrew C. Kuchins, director of the Russian and Eurasian Program at the Carnegie Endowment, writes on the subject, “On the U.S. side, the basis for a new U.S.-Russian partnership rests on reconfiguring U.S. foreign and security policy goals, which include (1) successfully conducting the war on terrorism, (2) a new urgency to preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their means of delivery, (3) peacefully managing the rise of China as a great power, and (4) achieving a stable, global energy supply…No one would seriously question the weight of these items or that they can be pursued effectively without Russian cooperation. In fact, no country except Russia could possibly bring as much to the table on these goals.”

On the Russian side, the conceptual basis for rapprochement was provided by the pragmatic Putin Doctrine aimed at ensuring the country’s revival through integration into the global system, which, in turn, depends above all on cooperation with the West. As Vladimir Putin has stated, the core of a “trusting partnership” with the U.S. is “a new interpretation of national interests of the two countries and also a similar perception of the very nature of present-time threats.”

As a result, Russian-American relations have in recent months reached, I am sure, the highest point in their history, since the time of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Proclaiming a cessation of rivalry, Presidents Putin and Bush have expressed their “commitment to promoting common values,” among which they mentioned human rights, tolerance, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, economic opportunity, and supremacy of law. The Russian-American Anti-Terrorist Group is no longer confined to Afghan problems only. It has expanded its mandate and is now tackling problems associated with Central Asia, the Indian-Pakistani conflict, Southeast Asia, and Yemen. It also takes measures to prevent nuclear, chemical and biological terrorism, and fights drug trafficking. The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty was signed, even though the Bush Administration at the outset had no intention of making any commitments in the nuclear field. And on June 6, 2002, the U.S. recognized Russia as a market economy, well before this recognition came from our main trade partners in the EU.

There are still many differences between Russia and the U.S.. Both have officially excluded each other from the list of potential military adversaries, yet both have kept the old lists of nuclear targets. But this is no sign of aggressive spirit, rather this calls for further reduction of strategic offensive arms: indeed, the remaining warheads (1,700 to 2,250) have to be targeted somewhere! There is no one else to be contained with such an enormous stock. Russia does not agree with America’s destabilizing decision to withdraw from the ABM Treaty, but it seems this decision would sooner have an impact on American-Chinese relations. Any national missile defense (NMD) that the United States may set up in the coming decades will constitute a serious obstacle for Chinese strategic weapons, not Russian. Many of Russia’s steps in its relations with Iran and Iraq, and also Russian supplies of missile technology to China cause disputes. However, Russia coordinates its actions in these areas with Washington and would never overstep the line to avoid confrontation with the U.S.. I suppose, America would act the same way. The still remaining issues are steel imports (although American sanctions affected Russia less than other steel producing countries), chicken legs, and the Jackson-Vanik Amendment. But try finding someone who does not have disagreements today. What matters is the willingness to discuss differences constructively and move ahead.

The U.S. and Russia no longer play against each other using major third countries as trump cards, as was the case before when Russia sought to aggravate, for example, American-European contradictions, while Washington had the same aims with regard to Soviet-Chinese relations. Partnership is quite visible, as borne out by the fact that during President Bush’s European tour in May 2002 the number of anti-American protesters in Moscow was considerably smaller than the crowds in Germany and France.

Observer Jim Hoagland has remarked that the American and Russian leaders are moving towards an era of Global Entente, which will diminish the strategic influence of Europe, China, and Japan on Washington and Moscow. And this is something that is already causing concern in the capitals of other great powers. I am in no way against the Entente that was born in the era of the First Concert. But I see no formal reasons why it should not be global and aimed not at restricting the strategic influence of Europe, China, and Japan but at promoting joint action.

After all, Russian-American partnership is no impediment to development of Russia’s relations with NATO. The alliance’s Secretary-General George Robertson is confident, “We are on the threshold of qualitatively new relations between Russia and NATO… What unites us is, in many ways, greater than what disunites.” Nor does partnership between Russia and the United States represent any handicap to G8 cooperation: At the latest summit in Canada, Russia acquired the status of a full-fledged G8 participant on the entire range of issues discussed. For the first time, Western countries empowered the Russian leader to carry out a collective assignment, bridging the gap in relations between India and Pakistan. Russia had not been entrusted with such a serious mediatory mission before.

The media in the West still tend to treat Russia with prejudice, but to a lesser extent than before. The country’s image today is better than ever. It is also better than in pre-Bolshevist times of the First Concert. A stereotyped opinion of an American journalist of that period was of “a Jew-hating tsar and the Jew-hating oligarchy [who] had so long perpetuated atrocities among the peasants” that it was hard to imagine if Christ ever turned up in a Russian village. Russia’s image is especially attractive against the background of the West’s other allies in the grand anti-terrorist coalition where the central role is assigned to a number of Islamic countries. Compared to these countries, Russia may with every reason be considered a prosperous democracy of a Western type. In addition, Russia’s image has also improved with the Western public coming to know better their future NATO allies. In all the countries, except Slovenia, to be admitted to NATO following the Prague summit, the governments only managed to stay in office for one term; everywhere it is the left, the former Communists, who are in power. In some of these countries, anti-Western and anti-American sentiments are spreading, and corruption is much more widespread than in Russia. Incidentally, 60 percent of Europeans and 68 percent of Americans favor Russia’s accession to NATO.

Moscow has turned into a potential strategic partner of the West with no harm caused to its earlier formed strategic partnership with China and India. The Russian-Chinese Comprehensive Treaty is more binding than any other agreement signed by Beijing. A pause in Russian-Indian relations, caused by Boris Yeltsin’s physical inability to get to New Delhi in the course of eight years, has ended, and both countries are now engaged in active cooperation. Russian-Japanese relations are on the rise, although over the decades they were completely concentrated on the issue of Russia’s South Kurile Islands, known in Japan as Northern Territories. At any rate, there are now signals coming from Tokyo indicating Japan’s willingness to set the territorial issue aside and get busy with other, less entangled ones. These may include, for example, the development of energy resources in Sakhalin, which involves the construction of the first-ever pipeline to take natural gas from the Sakhalin shelf to the Japanese Islands.

Meanwhile, the question arising time and again is: How lasting is Moscow’s turn towards partnership, and would it not return to the former, Soviet, confrontational paradigm? I see no reasons for that. Russia has neither strength, nor desire for confrontation. Putin is going to press ahead with his course, even despite the resistance from part of the elite and bureaucracy, which the president may just as well ignore in a country with a millennium-old tsarist political culture. But Putin by no means is a lonely figure. Rallied behind him is the advanced part of the intellectual elite, the more successful members of the financial and political community, and the petroleum, metallurgical, high-tech and other giants that have already broken out of the national shell and turned into international corporations.

FROM THE FIRST TO THE SECOND CONCERT

The main prerequisite for a resumption of the Concert is that it (and the “century of peace” it provided for) represents a mode of relationship natural for civilized states. It is natural for normal people to seek peace and tranquility. The purpose of the First Concert was confirmed if only by its long history, a record for all international systems (except, of course, for the longevity of the Treaty of Westphalia system created in 1648, which is only just about to die out). World War I was a result of a fatal miscalculation by several European governments —by Kaiser Wilhelm’s, in the first place—rather than irreversible malfunctioning in the mechanism of the First Concert. When the war ended, the Concert could have been restored, had it not lost two great powers for quite a while. One of these was Germany, which was given much harsher treatment in Versailles than post-Napoleonic France had been meted out in Vienna. The second was Russia where the Bolsheviks, seizing power in the 1917 Revolution, challenged directly the system of values and the way of life that existed in all other great powers, which resulted in the country’s isolation and self-isolation lasting for decades. The least governable system, that of Versailles-Washington, that found its expression in the impotent League of Nations, came to its end amid the flames of the bloodiest world war. A recreation of the Concert after World War II, now on a global scale, not just European, had prospects for being quite a practicable endeavor, considering the experience of the anti-Hitler coalition and the establishment of the United Nations, with the U.S. turning into a global player, and Germany, Italy, and Japan successfully integrated in the international system. But again, for reasons that are a separate theme, this system left out the Soviet Union, a country that was already controlling a good half of the world’s population. This made the world bipolar, divided by a big curtain. As the experience of the 20th century indicates, no Concert is possible without Russia, and, moreover, by the end of the century it became obvious that no Concert was possible without reviving new-old great powers, China and India.

By the late 1990s, Russia had carried out a revolution most important in its history: It created a world that was no longer divided by impassable lines. This facilitated the process of globalization, which has now reached almost all places on the planet. The fall of the “Iron Curtain” became decisive for the emergence (or recreation?) of a system of non-confrontational interaction between major powers.

September 11, 2001 and the events that followed provided additional arguments in favor of not so much unilateral action, as actions in the spirit of a new, Second Concert. U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell, characterizing the incipient anti-terrorist coalition, stated, “What is unique about the coalition… is that, except for about three or four countries, every other country on the face of the Earth has signed up.” Of course, one should not overestimate either the cohesion of the coalition, or the sincerity of its participants, or the contribution of some of them to the success of the common cause, but the coalition is a fact. For the first time since the era of the First Concert, all great powers with no exception, each proceeding from its own interest, have rallied to fight a common enemy—international terrorism. Certainly, we can in the future expect differences in interpretations of such notions as ‘terrorism’ and ‘countries supporting it.’ But for the first time in decades, those who are regarded as terrorists by a group of great powers have not become “freedom fighters” for another group of powers. For the first time we hear chords of the Concert, or Concerto, in global performance.

Coalitions “pro” are more viable than coalitions “contra.” This, however, does not mean that the latter are not viable. There is nothing like a common enemy to consolidate. The First Concert was directed against a former enemy, Napoleonic France. However, the powers that can form a Second Concert have different former enemies. The common enemy, terrorism, has come from the outside and on a global scale from the outset; the global fight against it as the joint mission of the orchestra has become an imperative. The enemy is very strong, and its strength is linked with Islam in its most radical forms. Although pointing out this linkage is considered as lacking in political correctness, “Islamic leaders who aver that Islam has no relation to terrorism engage in wishful thinking. The linkage is there and discernible, above all, in the ideological substantiation of terrorism and extremism. For this purpose, they employ the long known Islamic concepts that concern jihad, attitude to the unfaithful, suppression of all that is forbidden by the Shariah, and relationships with the powers that be.”

Of course, the creation of a Second Concert is a development that is far from certain and one that provokes numerous questions. Anticipating them, I would like to point out that the First Concert should not be idealized either. And the world today is not any worse than the one in which our ancestors lived in the 19th century.

At first glance, a Concert may look impossible in the conditions when the powers disagree on major issues, are divided into blocs, and have different basic values and cultural codes. But there was never unanimity in the First Concert; all major and even minor issues evoked bitter disputes. Members of the 19th century Big Six also participated in various blocs. Already during the Congress of Vienna, not without the assistance of the cunning Talleyrand, Austria, Britain, and France formed a temporary secret alliance against Russia and Prussia. Britain, a member of the Quadruple Alliance, never joined the Holy Alliance of the monarchs of Russia, Austria, and Prussia. And later, the countries broke into the Entente and the Triple Alliance. It is rather doubtful that members of the First Concert shared all the values. The difference between constitutional monarchy in Britain and Russia’s autocratic monarchy was much more significant than between today’s representative democracy in the U.S. and socialist democracy in China. On the contrary, the values associated with peaceful coexistence and the rights of the individual, as well as market principles in the economy, have in recent decades become practically universal. As for cultural values, these, whether it is good or bad, are being leveled out.

Martin Heidegger once remarked that there were two downfalls in the history of humanity: the first time in sin, and the second in banality. Modernism and post-modernism, representing, in essence, simplification of culture, are becoming a universal asset as a result of the information revolution and broad international exchanges. The only cultural entity that denies the Western system of values is based on Islam. In any case, China, India, Japan, and Russia do not oppose the process of globalization or Western mondialism. How can we talk of any concert if we have no agreement on how we read music and everyone interprets international law in his own way? Can a “century-long peace” be really possible with wars flaring up all around and the United States planning a series of armed interventions? However, international law in the 19th century was an even more ephemeral matter than it is today. And the European Concert in no way meant the absence of any wars and aggression. Great powers waged numerous colonial wars and conducted military operations on European periphery. Russia in the 19th century fought two wars with Persia and three wars with Turkey, it annexed Central Asia by force, etc. It was not a matter of no war as such, but, rather, a situation where major clashes were prevented between great powers. And the Concert performed this mission successfully, with only two hitches that led to the Crimean War in the 1850s and the Franco-German war in the 1870s. In our days it is just as difficult to imagine a situation causing a military conflict between major countries. Not least because almost all of them are nuclear powers. A potential hot spot is Taiwan, which may be destined to play the role akin to that of the Black Sea straits in the 19th century. That is, it may become a source of endless tension in relations between leading powers (in this case, between the U.S. and China). And although quite possibly the planned American interventions will not meet with universal approval, they, nevertheless, will not necessarily cause an end to concert activities. Tectonic shifts in the world system in the 21st century have created a situation where the strategy of territorial division and military containment is giving way to a strategy exercised during the First Concert, that is, cooperation in the area of security and economic engagement. These are obvious prerequisites for a new Concert, and the performers and the organizational format still remain unclear. However, the final answers will take a long time to come.

A Concert without U.S. participation will either be senseless or turn into a counterproductive anti-American scheme. The main question is whether the U.S. will be prepared to join in. In the long run and maybe in the medium term, undoubtedly yes. In the short term, more probably yes. Even the ode to America’s unilateral stance, the recently adopted U.S. National Security Strategy, carries the following statement: “America will implement its strategies by organizing coalitions —as broad as practicable —of states able and willing to promote a balance of power that favors freedom.”

Russia is actually already engaged in a global game of concert. So is the European Union; the question is only what kind of participation in the Concert this is going to be—collective or individual. All depends on whether the EU becomes an independent major player in the area of international and defense policy and how soon this may happen. If not, it will be represented by heirs to the performers in the First Concert.

Today, impediments are diminishing to overall global integration of India, which for decades was alienated from world affairs and culturally detached from the West. A decisive role in this matter was played by the deliberate policy pursued by Washington, which even before 9/11 had embarked on a course of partnership with New Delhi. Now, after a period of sharp Indian-U.S. contradictions over India’s nuclear programs, the two countries, as their leaders assert, are “natural allies.” It should be noted in this context that the chronically complicated Indian-Chinese relations are improving, albeit slowly, which means that one more obstacle is coming down on the way to a global Concert.

China’s participation in the Concert is the hardest to forecast: the U.S. is wary lest Beijing should claim the status of a second superpower and defy America. Indeed, China is capable of becoming an Asia-Pacific superpower in the coming twenty or thirty years, but it will have no potential to threaten American security. Nor desire to do so. “The further China moves along the way of modernization… the more important partnership with America is for it.” Today, the U.S. is China’s leading trade partner, so why threaten the goose that lays golden eggs? It is hard to predict the consequences of American troops’ arrival in Central Asia, just as those of the creation of NMD. There is a possibility of a new hotbed of tension emerging and nuclear missile stocks being built up. Or else, it is possible, on the contrary, that Beijing will revise its strategy in favor of greater moderation. I would agree with Henry Kissinger who maintains that Washington should let China understand that the U.S., while countering its hegemonic aspirations, still prefers constructive relations and will promote China’s participation in a stable world order.

The organizational format of the Second Concert does not look like a crucial problem. The First Concert was rather loose organizationally, having no clearly defined objective and setting no legal obligations. There was no entity like a European government, and there were only sporadic European congresses, most of all reminiscent of what we know today as G8 summits.

The Second Congress may be more formalized — for example, it may function on the basis of the UN Security Council. But this requires an expansion of the Council, with more countries represented in it, while the U.S. has to get rid of its prejudice against this body, which, as a matter of fact, is not easy. The G8 could also serve as the basis for the Concert, growing into a G9, a G10 and so forth. NATO could also offer a platform for the global Concert. By accepting ever more and weaker members and setting up the Russia-NATO Council, it has been turning from a serious military organization into a political association.

In this new status the alliance could opt for similar councils formed with other countries (it is already stepping up its partnership with Uzbekistan and Mongolia), or use Russian channels to establish contact with them. There are already forums functioning in the manner of a Concert—the World Trade Organization and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development that Russia is planning to join in the near future. It is quite possible that some entirely new format may be required.

The world is moving to and will arrive at a global Concert, despite all efforts to establish unipolar hegemony. It is on a concerted basis that problems of survival on Earth can be resolved, with the second, chaotic mega-scenario thereby forestalled. Whether it is a matter of non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, or preservation of habitat, or poverty, or epidemics, it has all got to be a matter of concern for all countries with influence, for, indeed, none of them can fly away to live on another planet.

The word “concert” derives not only from the Italian “concerto,” but also from the Latin “concerto” (compete). A concerto in music is a composition written for one or, more seldom, for several instruments and an orchestra. What is typical of a concerto is virtuoso solo performance and competition of the soloist with the orchestra. A symphony in which one instrument acquires a solo role on its own has ever since the 18th century been called symphonique concertante or konzertierende Symphonie.

I have nothing against symphony concerts, the supreme form, make note of it, of instrumental music.