This article is a shortened version of the paper written for the Valdai International Discussion Club and published in April 2015. Full text is available at http://valdaiclub.com/publication.

A narrative has taken hold around the world that might be titled “the return of Realpolitik.” From the happy days of globalization in the 1990s to the frenzied war on terror and associated counterinsurgency struggles of the first decade of the 2000s, the argument goes, great powers and geopolitics are back. Walter Russell Mead put this conventional wisdom well: “Whether it is Russian forces seizing Crimea, China making aggressive claims in its coastal waters, Japan responding with an increasingly assertive strategy of its own, or Iran trying to use its alliances with Syria and Hezbollah to dominate the Middle East, old-fashioned power plays are back in international relations.”

Many analysts portray current contestation as the leading edge of a full-blown conflict over the U.S.-led global order. That is the meaning of the oft-heard claim that “unipolarity” has ended and new conflict-prone multipolar order has emerged. That is what underlies the increasingly popular 1914 analogy likening China’s rise today to Germany’s pre-World War I ascent. Others reject this as alarming, claiming that the liberal global order is robust and able to continue absorbing new states into its ranks. As rising states like China grow, John Ikenberry contends, they “will have more ‘equities’ to protect, and this will lead them more deeply into the existing order.”

A careful look at power realities leads to a more nuanced position. Realpolitik is about the relationship between material capabilities – “hard power” in today’s parlance – and legitimacy, influence, the ability to achieve desired outcomes. From that perspective, power politics is not “back” after having been away on some vacation. It has always been here. It was here when the Cold War ended, when the Soviet Union collapsed, when the U.S.-led alliance of the “Broader West” expanded its aims and influence in the 1990s. Indeed, missing from Mead’s list of “power plays” is the country that remained highly active all along: the United States. What is different today is that power plays are more visible because other countries are pushing back harder. There is nothing new about China’s maritime claim or its views about the U.S. presence in Asia. Nor is there anything new about Russia’s dissatisfaction with the expansion of Western security institutions near its borders. What is new is the willingness of these governments to press their case more forcefully.

If the “return of Realpolitik” school is right, that contestation is likely to increase, especially if the dominant states go on declining while refusing to scale back the degree of global authority. For forceful efforts to upset the global order will be constrained and shaped in ways that make analogies to the past deeply misleading. Three limiting factors stand out: first, what we are witnessing is a power shift, not a power transition; second, major power war is for all practical purposes ruled out as system-changing option; and, third, the thick web of international institutions constrain challengers in novel ways. Together, these limits constrain the options of today’s dissatisfied powers and render the current order harder to dislodge than many suppose.

Power Shift, Not Power Transition

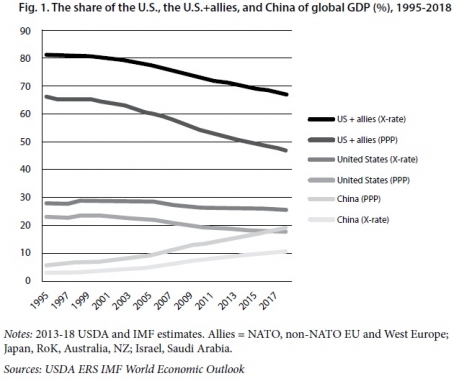

It has become commonplace to claim that the unipolar era is over or fast winding down. As Christopher Layne puts it, “the international system is in the midst of a transition away from unipolarity. As U.S. dominance wanes, the post-1945 international order – the Pax Americana – will give way to new but as yet undefined international order.” This implies momentous, system-altering change. The reality is subtler. Since the mid-1990s the United States’ share of global GDP has declined gradually. The far more significant shifts, however, have been the economic rise of China and the decline of U.S. allies.

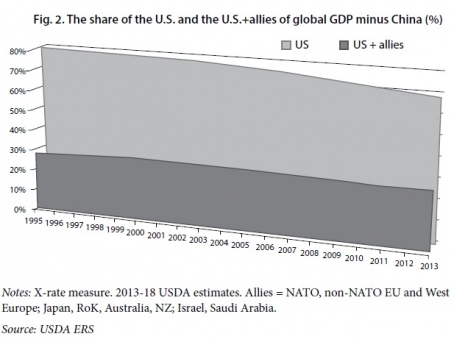

In other words, the power shift that has captured the imaginations of politicians and pundits alike boils down to China’s rapid economic growth. As Fig. 2 indicates, if China did not exist, or if China’s economic growth rates had mimicked Japan’s since 1990, there would be no talk of U.S. decline. The issue is not rising powers or BRICS or the rise of the east or the rise of the rest. It is China’s rapid GDP growth. China is in a class by itself – it stands above all other so-called rising or great powers as the only one with a plausible chance of achieving superpower status in the decades to come. For the moment, however, the only transition on the horizon is in gross GDP. Only on this one dimension of state capability is China about to become a peer.

Suppose we dispense with the term “unipolarity” and instead just call the system that emerged after 1991 a “one-superpower world,” and define a superpower as a country with the capability to credibly sustain security guarantees in Europe, Asia and the Middle East. That is, a superpower has the needed expeditionary capacity and alliance relationships, and is sufficiently secure in its home region, to organize major politico-military operations in multiple key world regions. The U.S. surely qualifies. And the fact that it has continued to sustain security alliances in the world’s key regions of Europe, East Asia and the Middle East undergirds the current inter-state order.

A true power transition or polarity shift would entail the end of a one-superpower world, either through the rise of a second superpower (the return of bipolarity) or through the rise of other great powers sufficient to make it impossible for the United States to sustain credible security guarantees to its allies (a no-superpower world, or multipolarity).

China’s economic rise warrants talk of polarity shifts and power transitions only if gross economic output is readily convertible into other key elements of state power. Based on the experience of past challengers, many scholars and commentators appear to think that the GDP/power conversion rate has remained constant over time, so that China, like Wilhelmine or Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union in the 20th century, might choose to ramp up to superpower status and succeed in relatively short order.

But as Steve Brooks and I detail elsewhere, this is misleading on two counts. First, past challengers were roughly comparable in population to the dominant power. When their gross economic output came within the range of the dominant state, their relative wealth and technological prowess followed suit, either surpassing, matching or at least approaching the hegemon’s. When it came to be seen as a challenger to Britain’s world position, Wilhelmine Germany, for example, was richer, more technologically advanced in key areas, and had a larger economy than Britain. By comparison, China’s huge population dictates that its economy can match U.S. output while still being dramatically poorer and less advanced. Even the Soviet Union, which used totalitarianism to compensate for relative backwardness, was much richer vis á vis the United States during the Cold War peak than China is today. And for the initial phases of the Cold War, Moscow matched or even surpassed the United States in key, strategically significant technological areas. China still has a long way to go before presenting a challenge of that nature.

Second, for a variety of reasons Brooks and I detail, it is much harder today to translate raw GDP into other elements of state capability – especially military capacity – than it was in the mid-20th century. Modern weapons systems are orders of magnitude harder to develop and learn to use effectively than their mid-20th century predecessors. China thus confronts a higher bar for peer competitor status than did earlier challengers from position of less wealth and lower indigenous technological capacity. As a result, the best estimate is that China will long remain in its current status as a potential superpower.

And add to that the demographic factor: China is not only a relatively poor challenger (though big) compared to past risers, this is the only transition in history in which the challenger gets old before the dominant state. In all previous power transitions, both rising and declining states were demographically young. But China will face the fiscal and other challenges of an aging population sooner and more severely than the United States will. The system is changing; China has risen, the EU and Japan have declined. But the United States has not declined, and will not decline soon, to the point that it ceases to be the world’s sole superpower.

No Hegemonic War

How do you overthrow a settled international system? Rising, dissatisfied powers want to change the system, dominant states resist, clinging to their perquisites. Each thinks it has the strength to defend its position. The main way this contradiction was resolved historically – at least, if theorists like Robert Gilpin are right – was an all-out war involving all or most great powers. Not only did hegemonic war resolve the contradiction between the underlying distribution of capabilities in the system and the hierarchy of prestige or status, it also served as “a uniquely powerful agent of change in world politics because it tends to destroy and discredit old institutions and force the emergence of a new leading or hegemonic state.”

Thankfully, such a war is exceedingly unlikely to emerge among states armed with secure second-strike nuclear forces, whose core security, future power, and economic prosperity do not hinge on the physical control of others’ territory. Can something else take its place? Not according to a new book by Randall Schweller. Other destructive events one can imagine, such as a global economic crash, pandemic, or environmental catastrophe, may wreak widespread destruction but they are not driven by political logic and so cannot perform some political functions. As Schweller argues, “it is precisely the political ends of hegemonic wars that distinguish them and the crucial international-political functions they perform – most important, crowning a new hegemonic king and wiping the global institutional slate clean – from mere cataclysmic global events.” On his view, only hegemonic war can force the emergence of a new hegemon, clarify power relations, and wipe the inter-state institutional structure clean, leaving a tabula rasa for the newly anointed hegemon to write new rules. “The distasteful truth of history,” Schweller writes, “is that violent conflict not only cures the ill effects of political inertia and economic stagnation but is often the key that unlocks all the doors to radical and progressive historical change.”

We can look at the conditions under which the current system took shape for clues. World War II is widely seen as the most destructive of modern history. But while it knocked several great powers down, it yielded ambiguous lessons concerning the relative importance of American sea, air and economic capabilities versus the Soviet Union’s proven conventional military superiority in Eurasia. Even though it failed to clarify the U.S.-Soviet power balance, the war radically increased the economic gap in the United States’ favor not only by giving it history’s greatest Keynesian boost but also by physically destroying or gravely wounding all other world’s major economies. It created the preconditions for the Cold War, without which America’s order building project could never have been as elaborate and extensive. It left the Soviet Union’s armies in the center of Europe, creating the conditions without which NATO would never have been created. This enabled history’s most deeply institutionalized and long lasting set of alliances by giving Washington the incentive to overcome domestic resistance to the costs of building hegemony while conferring unprecedented U.S. leverage over its allies to bend them to its will. Not only that, it left in its wake unprecedented humanitarian and economic crises that only the United States had the wherewithal to address in a timely fashion.

It is exceedingly difficult to imagine any set of conditions emerging that is remotely as conducive to systemic change. If Gilpin was right that “hegemonic war historically has been the basic mechanism of systemic change in world politics,” and if most scholars are right that such a war is exceedingly unlikely in the nuclear age, then systemic change is much harder now than in the past. With world war-scale violence off the table, any order presumably becomes harder to overthrow.

It follows that scholarly and popular discussions radically underestimate the difficulty of hegemonic emergence and therefore overestimate the fragility of the American-centered order. Standard treatments of systemic change do not capture crucial effects that conspired to facilitate the current order that emerged under U.S. auspices. Uniquely in modern history, World War II destroyed the old order, clarified power relations between the U.S. and its allies, and yielded a bipolar structure that was uniquely conducive to the U.S. order building effort in the ports of the international system over which it held sway. In this light, expectations of a coming “Chinese century” or “Pax Sinica” seem fanciful.

Institutions and Strategic Incentives

Today’s international system is far more thickly institutionalized than those in which previous power shifts occurred, and institutions play a far more salient role in U.S. grand strategy than was the case for its predecessors at the top of the inter-state heap. There are good reasons to worry that this may induce rigidity to the system. And if that is so, then today’s order may well be far less amenable to accommodation than its defenders argue. Key here is the close interaction between institutions and grand strategy.

Woven through the speeches of President Obama and other top U.S. officials is a robust restatement of the traditional U.S. commitment to multilateral institutions as a key plank in a grand strategy of global leadership. According to U.S. foreign policy elites – and reams of political science research on institutions – the focus on leadership and institutions brings benefits to the United States from institutionalized cooperation to address a wide range of problems. There is wide agreement that a stable, open, and loosely rule-based international order serves the interests of the United States.

Most scholars and policymakers agree that such an inter-state order better serves American interests than a world that is closed – i.e., built around blocs and spheres of influence – and devoid of basic agreed-upon rules and institutions. As scholars have long argued, under conditions of interdependence – and especially rising complex interdependence – states often can benefit from institutionalized cooperation.

Arguably, the biggest benefit is that a complex web of settled rules and institutions is a major bulwark of the status quo. Over a century of social science scholarship stands behind Ikenberry’s signature claim about the “lock-in” effects of institutions. Path dependence, routinization, internalization and many other causal mechanisms underlie institutions’ famed “stickiness,” that is, their resistance to change. These stand as important allies of status-quo oriented actors – and major adversaries of revisionists. Needless to say, this same stickiness can vex those who like the status quo in general but might want to revise rules – as in the case of Europe’s and to a lesser extent the United States’ efforts to alter norms of lawful military intervention in sovereign states. And the BRICS countries can use existing rules to push back against changes they dislike, and can exploit ambiguities in the normative order to defend their prerogatives. But given that the U.S. remains essentially a status quo power and that the existing institutional order reflects its core preferences, overall the stickiness of institutions works to its advantage and is a major argument for defending the order.

The incentives for the United States to foster and lead the institutional order are strong. But that does not mean that there are no downsides. Embedding its grand strategy in institutions may curtail U.S. options and reduce flexibility in other ways. First is the problem of exclusion. Foundational elements of the U.S. grand strategy of leadership are exclusionary by nature. U.S. officials believe that the maintenance of security commitments to partners and allies in Europe and Asia is a necessary condition of U.S. leadership. And those commitments are exclusionary by definition. As long as those commitments remain the bedrock of the U.S. global position, states against which those commitments are directed – especially China and Russia – can never be wholly integrated into the order. The result is to foreclose an alternative grand strategy of great power concert.

Securing the gains of institutionalized cooperation today may come at the price of having alienated potential partners tomorrow. This problem grows with the power and dissatisfaction of excluded states.

Second and more speculatively, U.S. policymakers may confront another set of constraints in the longer term. Key here is the article of faith among U.S. policymakers that all the parts of the U.S. grand strategy are interdependent: U.S. security commitments are necessary for leadership that is necessary for cooperation that is necessary for security and for U.S. leadership in other important realms. The result is to create apparently potent disincentives to disengaging from any single commitment. Pulling back from U.S. security guarantees to South Korea or Taiwan or NATO may make sense when each of these cases is considered individually. But if scaling back anywhere saps U.S. leadership capacity everywhere, any individual step toward retrenchment will be extremely hard to take. When U.S. officials are confronted with arguments for retrenchment, these concerns frequently come to the fore.

In sum, the institutional order makes it hard for states that are unhappy with U.S. leadership to push back. At the same time, it makes it harder for the U.S. to scale back its claim to leadership. These effects were strongly in evidence in the crisis over Ukraine. NATO’s exclusionary essence was an important driver of Russian policy. Political and organizational incentives within the institution, moreover, made it very hard to agree formally to close the door to further expansion to Ukraine even when many NATO allies supported such a move. The result appeared to be a case in which the incentives intrinsic to the institution pushed towards conflict with a major power. The ability to accommodate rising powers appears to be constrained by the central role institutions play in the leading state’s grand strategy.

* * *

The bottom line is to expect a tougher, harder-to-manage world in which the shifting scales of world power make cooperation harder and periodically generate incentives for militarized contestation. But talk of a polarity shift or power transition overstates the case. Historically, major, hegemonic wars played this role. Schweller makes a strong case that other major events lack the political mechanisms required to reorder the international political system. The net implication is that displacing the current U.S. dominated inter-state order is much, much harder than the current commentary allows. If that were not enough, the power shift currently underway is far more modest than the hyperbolic rhetoric used to describe it. It amounts to China reaching peer status in terms of gross economic size. Yet for a number of reasons Beijing faces a higher bar for translating that economic output into the other requisites of superpowerdom, not least because it is comparably poor relative to the system leader and barriers to entry in the top end military competition are higher than ever. And if all that weren’t enough, China confronts a settled, ramified institutional order that stacks the deck against revisionism.