This article was originally published in Russian in Pro et Contra, No.14, July-October, 2010, as part of Russia-2020 project.

Russia has entered the third cycle of its post-Soviet history. Although the contours of this cycle are not yet clear, we are already in it. The results of the cycle will be summed up around 2020, and it is precisely these results that will form the image of the country.

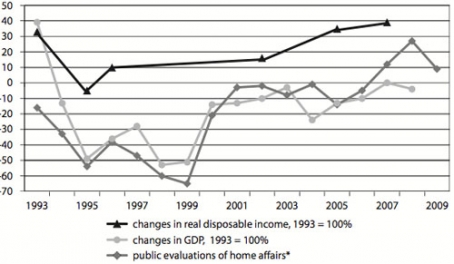

Indeed, if we look at the 20 years of the post-Soviet history from a bird’s eye view, we will be struck primarily by the presence of two periods that, by their main characteristics, are as different as night and day. The first period came during the 1990s and can rightfully be called a period of transformation. It was marked, first and foremost, by large-scale institutional changes and by a no less substantial restructuring of the economy. Post-Soviet Russia’s major political and economic institutions were formed, in their first outlines, precisely during these years. At the same time, restructuring of the economy occurred in the form of a deep transformational recession (Russia’s GDP contracted by as much as 35-45 percent) and was accompanied by a dramatic fall in living standards (real disposable income in 1999 was 46 percent of its 1991 level). Another characteristic of this cycle [the author’s arguments in favor of this term are given below – Ed.] was the chronic budget deficit – in the absence of sources with which to cover it. This indicator actually reflected the high degree of political instability and the weakness of the state, as well as its inability to collect taxes and face pressure from the opposition demanding an increase in expenditures. The extremely low level of public support of the acting leadership throughout this period – or rather, the high level of “not supporting” those leaders (Fig. 1) – completes the picture.

Figure 1. Changes in real disposable income, GDP and public evaluations of home affairs

* The indicator of public evaluations of home affairs is the difference in positive and negative answers to the question asked in the polls by the Levada Center (VTsIOM before 1993): “Is the country developing in the right direction or is it heading for a dead end?; a value below 100 points indicates that the balance between approvals and disapprovals is negative.

As if by magic, everything began to change in 1999. The second period of Russia’s post-Soviet history can rightfully be called a period of stabilization as stabilization was its main slogan and goal. This period was characterized by consistent and impressive growth in the country’s GDP (at an average rate of about 7 percent), and by the fast-paced growth of incomes. Moreover, the income growth rate exceeded the growth rate of GDP, while in the 1990s its rate of decline outpaced the GDP fall. Additionally, this period was marked by a consistent budget surplus, which was evidence of the reversal of fundamental political tendencies – the government was no longer under siege. This was also evidenced by changes in public evaluations of the state of affairs in the country and its development course (Fig. 1). Finally, according to experts, yet another feature characterizing the period of stabilization was the deceleration and attenuation of institutional reforms (compare, for example, the behavior of Russian figures in the Bertelsmann Foundation’s Transformation Index: according to the Status Index, Russia moved from 41st place in 2003 to 65th place in 2010, while it moved from 31st to 107th place on the Management Index).

The financial crisis of 2008-2009 marked the conclusion of the second cycle. While noting the striking differences between the two cycles, one cannot but notice that the trends that were indicative of the second period broke, or at least were enfeebled. For the first time since 1998, GDP did not increase in 2009, but contracted; moreover, the extent of the reduction (by 7.9 percent) was comparable only to the pace of economic decline of 1992-1994. In 2010, Russia demonstrated economic growth, albeit at substantially lower rates than before (less than 4 percent). Whereas from 2000 to 2007 the annual income growth stood at 9-15 percent per year, in 2008-2009 a growth was registered, but at a minimal level – 1.9 percent in 2008, and 2.3 percent in 2009. In 2010, income growth did not exceed 3-4 percent. Lastly, the budget once again (for the first time since 1998) was in deficit; moreover, the extent of the deficit (5.9 percent in 2009) was comparable to that of 1995-1997. Experts (including those in the Russian government) do not expect a return to the previous figures of growth in the economy and incomes, and the government hopes to balance the budget no earlier than 2015. What new shape will social and economic development assume? What will the new decade be like?

CYCLES AND CYCLICITY: A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In the 1990s, the processes that took place in the post-socialist countries were primarily considered within the framework of the transitology paradigm, according to which these processes had a predetermined “end point.” Empirically their development was conceptualized as a story of intermediate stages and various deviations along the trajectory towards this goal. Disillusionment with this paradigm in the early 2000s was rapid (see the notable debate in the Journal of Democracy in 2002), and its unpopularity over the following decade is comparable only to its popularity in the preceding years.

As Russia pushed away from this paradigm, a new position on Russia and other CIS countries became increasingly widespread. According to this view, the period of reformist “disturbance” associated with the collapse of the socialist economy and the Soviet empire is regarded as an anomaly and a result of an imbalance and general loss of equilibrium; accordingly, as this disturbance subsides and balance is restored, the political and social structure will return to something essentially similar to its original state. The concept of the existence of a certain authoritarian/totalitarian/paternalistic archetype of Russian statehood – immutable, organic and the only fully realized system of power relations that can survive periods of crisis or decline, but which remains essentially unchanged – once again acquired popularity.

However, the clear antisymmetry of the first and second approaches, which consider one of the two states of society as abnormal and the other as normal or normative, as well as the series of “color revolutions” on the territory of the former Soviet Union, gave impetus to a third view of development – to the argument about the oscillatory nature of the historical and political evolution of the post-Soviet countries – and refreshed interest in the idea of cyclicity (see H. Hale. Regime Cycles: Democracy, Autocracy, and Revolution in Post-Soviet Eurasia. World Politics, Vol. 58, No 1, Oct. 2005). Cyclicity in this context is understood as the instability of hybrid regimes associated with a divided elite and weak institutions; fluctuations between periods of dominance of authoritarian and paternalistic practices, on the one hand, and democratic bursts, on the other, are explained by the inability of the elite to achieve consolidation on the basis of established conventional rules of coexistence and cooperation (such cyclicity with reference to Latin American countries is described in G. O’Donnel. Delegative Democracy. Journal of Democracy, 1994, No. 5 (1)).

There is, however, a broader, more general interpretation of cyclicity which is not related to the problem of hybrid regimes and which could be called socio-historical. Here we primarily have in mind the famous description of the cycles of American history given by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. (The Cycles of American History. Boston, 1986). Under this view, cyclicity is regarded not as an inability to find a state of equilibrium, as is in the previous case, but as the natural model of society’s historical existence, movement “by tacks,” with periods of public exaltation and focus on social interests (liberalism in the American sense of the term) followed by periods of concentration on private interests, social apathy and preferences for the proven “old” forms and the status quo over any reforms and innovations (conservatism).

Attempts have been made to apply this pattern to Soviet-Russian history (G.W. Breslauer. Reflections on Patterns of Leadership in Soviet and Post-Soviet [Russian] History. Post-Soviet Affairs, 2010, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 263–274). However, public demand’s mechanisms of influence on political practice in the Soviet Union and in post-Soviet Russia differ significantly. Although a semi-authoritarian, paternalistic regime strives to reduce society’s direct influence on the government, it is in fact very concerned about public opinion, which it views as an important resource of maintaining power. In its turn, public opinion enjoys significant autonomy from the government and is inclined to view its relationship with the authorities as a contract, in a sense. For these reasons, the prevalence of the hypothesis of cyclicity in the Soviet era seems to be premature and requires special research.

Finally, there is a popular concept of “political business cycles,” which examines how political competition effects macroeconomic policy. On the other hand, there is a widely accepted idea that macroeconomic behavior has a significant impact on political trends and public preferences.

However, since the subject of my attention is a specific historical period in the life of Russian society I would say that the three interpretations of cyclicity discussed above are, in fact, directed at three important domains of social interaction that in reality are connected by strands of mutual influence, interdependence, and interpenetration. Macroeconomic fluctuations violate the established forms and modes of cooperation and coexistence of the elites, and stimulate the revision of widely held views inherited from the previous period. At the same time, shifts in social attitudes stimulate political activity among the elite groups and form a demand for programs that would change the rules of the game and economic priorities to reverse economic behavior.

Schlesinger’s core concept is the idea of the autonomy of the fluctuations of social attitudes towards leaders’ political initiatives and their policies; the question of the dependence of these fluctuations on economic cycles remains unresolved. This article attempts to provide an insight into the problem of cycles in the post-Soviet history of Russia from the perspective of the three indicated interacting levels: 1) the evolution of the prevailing public attitudes, 2) changing rules of interaction among the elite, and 3) changing macroeconomic trends that have a decisive influence on the ideas of both society and of the elite with regard to acceptable patterns of social development.

It should be noted that Schlesinger understands a cycle as interchangeability of three phases: a period of dominance of the public interest (the liberal phase), the transition phase, and the phase of concentration on private interests (the conservative phase) – i.e., the full beat of the pendulum. In this paper, however, the notion of a cycle is used mainly in the sense of a “swing of the pendulum” that involves a period of development, the peak and attenuation of the dominant trend, implying thereby that the continuation of the last phase becomes the beginning of a new cycle, opposite in direction, but passing through the same stages. These two opposite cycles form a “big cycle” (a cycle proper in Schlesinger’s understanding). Enlargement of scale in the analysis of cyclicity of post-Soviet history allows to focus on the mechanisms of “switching” between the phases of the “big cycle” and track the correlation of these phases with the economic cycles.

THE THIRD CYCLE: THE MACROECONOMIC DIMENSION

One essential observation should be made for an accurate analysis of the differences between the first two cycles of Russia’s post-Soviet history and the character of the transition from one to another. The crisis of 1998 undoubtedly triggered this transition: it struck a crushing blow to the potential of the oligarchic groups, and made it possible for the government to freeze and devalue (due to a sharp weakening of the ruble) a significant part of its debt and construct an almost deficit-free budget. Finally, although the devaluation of the ruble led to a significant reduction in the population’s incomes, it also enabled the country to quickly move to the phase of dynamic growth through meeting the domestic demand as a result of the reduction of imports.

At the same time, the transition to the phase of growth was not exclusively the result of these changes. It is significant that all of the countries of the former Soviet Union, independent of the economic policies they pursued, their economic structure, or their political situation, experienced economic growth from 1997-2000. The reason clearly lies in the fact that by the end of the 1990s, restructuring of the main sectors of the economy and of property relations had largely been completed, and a new system of internal and external markets had been built that paved the way to economic recovery. In Russia, economic growth was first recorded in the second half of 1997. The crisis of 1998 played the role of a trigger mechanism: the beginning of a new, recovery phase of the transformational cycle in the economy coincided with the beginning of a new political cycle.

How does the Russian crisis of 2008-2009 look against this background? From the very beginning it was the subject of a sharp controversy among those who believed it was caused primarily by the external impact of the global financial crisis, and those who thought that such an impact was only the pin that popped the “internal bubble.” However, the cumulative effect of the crisis leaves supporters of the first point of view without a chance: in 2009 Russia demonstrated the highest reduction in GDP among the 25 largest world economies (-7.9 percent, while the GDP of Russia’s closest “competitor,” Mexico, fell by 6.5 percent). The fall from its pre-crisis growth (8.1 percent in 2007) to the “bottom” of the crisis amounted to a 16-percent loss (its closest “competitors,” Mexico and Turkey, saw 9.8 and 9.4 percent falls, while other countries experienced an 8 percent drop, i.e., two times less than Russia). Compared with other economies, Russia suffered particular losses in trade, construction, and financial services; Russia also led in the decline of consumer demand. All these factors point to a general “overheating” of the Russian economy prior to the crisis and to the direct “overheating” of consumer demand.

Indeed, economic growth in Russia at the turn of the 1990s and the 2000s had a restorative character and relied on the expansion of exports and on domestic demand (import substitution). In the mid-2000s, it was supported by significant capital inflows into the country, which provided a rapid growth of incomes and consumer demand, as well as fast expansion of crediting of enterprises and consumers. However, the rapid growth of incomes and domestic demand led to a swift expansion of imports; as a result, the further growth of incomes had an increasingly lower stimulating effect on the economy. The growth model based on the rapid expansion of domestic demand hit the ceiling, and the financial crisis yanked out support in the form of massive capital inflows.

Today, the low economic growth rates (2.5-4 percent per year) and the low rates of income growth (or the stagnation of real incomes) seem to be the most likely inertial scenario for the coming years (given a favorable situation in the commodity markets). Also, the government will most likely lack the means to simultaneously stimulate the economy and fulfill its social obligations, which will tell on the budget deficit.

LIBERAL AND CONSERVATIVE PHASES: THE RUSSIAN VERSION

If we analyze Russian history of the past 20-25 years with regard to trends in social expectations and preferences and their effect on the political sphere, we will again see several stages and two major tendencies.

The first stage, from the late 1980s to the early 1990s, is characterized by the dominance in public opinion and public discussion of two fundamental political concepts that in many ways determined the direction of political development. The first concept was that of “reform.” The past and current states of affairs were assessed extremely negatively and were characterized as a “standstill” and as “stagnation,” while the alternative and the desired future were associated with deep “reforms.”

The second major trend of social ideas was the preference for decentralization. Decentralization is understood broadly here, as the autonomy of enterprises, the expansion of citizens’ economic and political rights, and the independence of different branches and institutions of power, of NGOs, and of the press. In general, decentralization should be understood as the idea of transferring rights and powers from higher levels of hierarchical structures to lower levels, the idea of splitting and distributing power among different levels and institutions. Preferences in favor of decentralization were graphically manifest in the political upheaval of 1991 and the policy of the first post-Soviet government of Russia: free elections, free press, the liberalization of prices and of economic life, the provision of significant autonomy to the regions, and the reduction of the powers and zone of authority of the central government.

However, over the next five years (1993-1998) there was a growing disappointment with the results of movement in this direction, and accordingly, with the key concepts that defined it (“reform,” “market,” etc.). This disappointment reached its peak in 1998-1999 (Fig. 2), and the preferences and political doctrines dominant in the public consciousness in the 2000s ultimately proved to be diametrically opposed to those noted in the first stage.

Figure 2. Changes in the public support of the market and the reforms and changes in public evaluations of the state of affairs in Russia

Notes:

* The indicator of support of the market was calculated using the distribution of the respondents’ responses in the polls conducted by the Levada Center (VTsIOM before 1993) about their attitude to the transition to the market economy: the sum of the double value of negative answers and the value of undecided responses was subtracted from the sum of the double value of responses favoring fast transition to the market and the value of responses favoring gradual transition.

** The indicator of support of the reforms was calculated using the distribution of the respondents’ answers in the polls conducted by the Levada Center (VTsIOM before 1993) concerning the need to continue the reforms: the sum of the double value of negative responses and the value of undecided responses was subtracted from the double value of positive responses.

The new period was noted for two central concepts – “stability” and “recentralization,” which were given, in the political language of the time, a common label of “power vertical.” In the system of values, stability became an absolute priority compared to the idea of changes and reforms; the latter were recognized only to the extent that they did not contradict the interests of stability. Simultaneously, the return of authority from the lower levels of the social hierarchy to the higher ones was invariably met by an approving or neutral attitude on the part of society. Whereas in the previous cycle the underlying trend was the pursuit for “splitting” power (one can recall the significant role that the Duma, the Constitutional Court, the institution of regional governors and independent media played in political life along with the executive authorities), now the guarantor of stability seemed to be a certain image of syncretic power exerting a decisive influence on most spheres of social life. Accordingly, the significance of the separation of powers, the autonomy of territories, unrestricted media, and political competition was sharply reduced in the eyes of society.

PRECONDITIONS OF THE SECOND TRANSITION: THE EROSION OF VALUES

Deep disappointment with the results of the policy associated with the concepts that had been favored by society during the preceding period became the most important factor for the popularity of the new political ideology that dominated the past decade. It became clear that as the policy of stabilization was reaching its goals, public demand for stabilization began to decline. The notions of “reform” and “market” gradually resumed their forfeited positions (Fig. 2). An analysis of the trends in the descriptions used by people to assess the political processes of the 2000s shows that the beginning of this period was marked by a sharp reduction in the number of people who would define the situation as “chaos and anarchy” and an equally fast rise in the number of people describing it as “development of democracy.”. Since the mid-2000s, the share of answers for “chaos and anarchy” continued to decline rapidly, the share of answers for “development of democracy” was rising very slowly, while the number of “undecided” responses showed a rapid increase (Fig. 1). Whereas during the first stage the reduction of uncertainty and turbulence was seen as an unquestionable value, in the second stage it is the quality of stabilization and its prospects that became increasingly relevant.

Importantly, the political practices of the 2000s consistently followed the recipes for “recentralization” and generally received approval from the population; however, the behavior of social preferences showed shifts in the opposite direction. For example, a multiparty system was supported in the early 2000s by approximately 45 percent of respondents, and 40 percent did not support such a system; in the late 2000s, the share of the former exceeded 50 percent, while the latter point of view was slowly losing popularity. This is all the more remarkable since the idea of the “dominant party” was advocated ever more persistently in the official political rhetoric of the second half of the 2000s. A similar trend can be observed in the responses to the question “Do we need a strong opposition party that can influence the government?” In the 1990s and the early 2000s, positive responses accounted for 50-60 percent and negative responses made up 21-25 percent; in the late 2000s, positive responses made up 56-61 percent, while negative responses, 16-20 percent. According to the surveys, the institutions of political competition – and, correspondingly, the very concept of “political opposition” – have very little authority; at the same time, demand for an alternative to the monopoly of “syncretic” power has grown.

A similar trend can be found in assessments of the notion of “order.” In the second half of the 2000s, the importance of this concept was no longer absolute as compared to the turn of the 1990s and the 2000s. Specifically, the question “What is more important: order or human rights?” drew a 60:27 distribution of responses in favor of order in 1997; in the late 2000s supporters of order made up just over 50 percent, while supporters of human rights constituted about 40 percent of the respondents. Finally, when asked to make a choice between democracy associated with disorder and order associated with suppression of freedoms, the respondents at the turn of the 1990s and the 2000s chose order at a ratio of 75-80 percent against 9-11 percent staunch supporters of democracy; in the late 2000s, the former group comprised 60-70 percent, while the share of unconditional supporters of democracy was about 20 percent.

These figures show, though, that the point at issue is not yet a radical change in public attitudes; rather, as other polls indicate, people speak in favor of paternalistic models. (It is worth remembering that the ideological and political pluralism of the most popular Russian media is officially restricted; society is largely cut off from the arguments of those who support decentralization and political pluralism.) At the same time, the above data suggests that the idea of the benefits of centralism and “syncretic” power is called into question in the public mind – preference for the corresponding models is weakening, and the logic of centralization seems largely exhausted.

Importantly, the political concept of “centralization” during the 2000s was popular not only due to the repulsion from previous experience, but also due to the stable and rapid growth of the economy and incomes. The latter seems to be a consequence of the former. The crisis of 2008-2009 broke the cause-effect relationship between the processes that had been formed in the mass consciousness in the 2000s and demonstrated that centralization (“verticalization”) of power alone cannot be an engine of economic and income growth. A sharp slowdown in economic and income growth can have a no less dramatic effect on the public perception of stability. Stability appears to be an unquestionable value when society is leaving a period of high uncertainty or when it is experiencing a period of economic growth; in the latter case “stability” implies the “stability of positive changes.” When these factors stop working, stability, when placed against the background of low or negative income growth, will increasingly and inevitably take on a different color in the perception of society and will increasingly be thought of as stagnation.

In this instance, I wanted not so much to give a more accurate picture of Russians’ social attitudes in the late 2000s, as to point to the significant contextual dependence of preferences given to some political paradigm during a concrete historical period. Most Russians were in no way staunch democrats at the turn of the 1980 and the 1990s, but it is also unlikely that they are supporters of the idea of a “strong hand” and centralism today. The changing parameters of the social and economic context (the presence/absence of instability and the presence/absence of economic growth) lead to a shift or a change in the dominant political preferences and re-evaluation of certain socio-political doctrines.

THE ELITE: AN “IMPOSED CONSENSUS” AND PUBLIC COMPETITION

The influence of economic behavior on political trends occurs mainly along two interacting lines: on the one hand, the social well-being of the population changes, and accordingly, its political assessments and preferences change; on the other hand, economic behavior affects the mood and strategies of elite groups, who have the resources to protect their economic interests. As is well known, it is the divisions among the elites projected onto mass expectations and assessments that form political demarcations and lead to the emergence of political competition (such is the general rule of Schumpeter’s model of political competition).

An analysis of the changes in interactions among the elites in Russian post-Soviet history shows that there were two periods marked by opposing tendencies. In the second half of the 1990s, there emerged a system under which elite groups possessing resources could form their political representations and build the corresponding political infrastructure (media, political parties and organizations) in order to consolidate public support and use it in competition for resources and authority. This occurred both in the federal political arena and at the regional level, including in big cities. In the 2000s, a reverse system took shape: elite groups abandoned their claims to political representation and chose not to appeal to the people in the struggle for their interests in order to maintain their resources and authority (“the rejection of politics”).

This new situation, which constitutes one of the fundamentals of the “Putin system,” can be called an “imposed consensus” (the use of the term “imposed consensus” here differs somewhat from the interpretation proposed by Vladimir Gelman with regard to the electoral cycle of 1999-2000 in Russia). Such a consensus relies on the ability of the dominant player, representing power, to block the politicization of inter-elite conflicts and their transmission into the public sphere with the help of sticks and carrots. However, this “consensus” was formed and maintained in a situation of continuous economic and income growth, which significantly reduced the severity of the conflicts: opting for confrontation did not look rational, since the preserved status quo or even a slight loss amid the growing economy was much more attractive than the prospect of total loss of one’s “position on the market.”

The new economic situation and the stagnation of incomes and of the economy will likely lead to the disintegration of this system. As long as the market grows, the game is centered on the division of additional income and the majority of participants are winners; in a stagnant market, actors have nothing to share but the resources they already have, and someone’s winnings mean others’ loss. Finally, in a shrinking market, the game is reduced to a battle for the redistribution of losses, and there are always more losers than winners. In addition, during the phase of growth, the population is inclined to look favorably on the authorities and the established status quo, which reduces the potential efficacy of elite groups’ appeals to the public; during the phase of stagnation or of decline in income, the population’s attitude towards the established rules and hierarchies becomes increasingly critical and, accordingly, the effectiveness of the aggrieved elite groups’ actions in the public sphere increases.

Thus, during economic stagnation or weak growth, the combined effect of these factors will contribute to the destruction of the “imposed consensus” and to the aspiration of the elite to return to the practice of public competition by politicizing inter-elite conflicts. In turn, public competition among the elites will stimulate a differentiation of public opinion and formation of groups supporting the new political forces.

DEFERRED PROBLEMS AND THE EFFECT OF WEAK GROWTH

In fact, the proposed scenario does not look very original. To a certain extent, the Russian crisis of 2008-2009 and the impending phase of Russian history can be analyzed in the context of the crisis of the South Asian countries in the late 1990s. Rapid growth in developing countries frequently allows society and the ruling groups to ignore the unfinished transformational changes and pushes the problem of bad institutions into the backyard. Economic growth goes hand in hand with the growth of corruption, which for a certain period even looks like a stimulating factor – it helps overcome institutional barriers, contributes to the accelerated concentration of capital, and allows for the redistribution of social costs and the use of “purchased” advantages in order to break into new markets. The negative effects of corruption look like an “acceptable evil” against the background of the obvious successes of the economy and the fast growth in incomes of the most active social strata and groups. However, a slowdown or cessation in this growth radically changes the situation: institutional problems come to the foreground of public attention, while corruption and the principles of “friendly capitalism” (with regard to Russia it is more correct to speak of “clan-bureaucratic” capitalism) turn into a major social irritant.

In Russia, the accumulated reserves allowed the government to alleviate the immediate financial and social consequences of the crisis of 2008-2009, but an exit from the crisis in Russia would be considered only upon a return to high rates of economic growth. Low rates of growth, while entirely adequate for developed economies, are not acceptable when it comes to maintaining social stability in developing countries with a weak institutional structure. The high level of income inequality means that low rates of growth have no tangible effect for the majority of the population. And the attempts of the “market barons” to reallocate the costs associated with the deteriorating market situation arouse sharp public discontent.

Thus, if the slowdown in economic and income growth awakens “dormant problems,” what are the sore problems that may come to the center of public attention and consolidate the discontent? These are, above all, corruption and the principles of “clan-bureaucratic capitalism.” Russia’s return to a period of open political confrontation and mass politicization will – with high probability – be carried out under slogans associated with the notion of “fairness.” Demand for democracy at the turn of the 1980s and the 1990s was associated with the desire to get rid of total control, acquire more rights and freedoms, including the freedom of enterprise, and gain independence from the authority of the government. The new demand for democracy may be fundamentally different: it will most likely involve a struggle for more equitable income distribution, equal opportunities and greater control of society over the government. In this sense, it is likely to be more left-leaning in content and spirit than its predecessor 20 years ago.

The second most important and most likely line of development of the new political conflicts is the opposition between the “center” and the “regions.” Regional stratification in Russia means no less (although it possibly implies more) than social stratification. Furthermore, the issue of regional autonomy is closely tied to the issue of equitable distribution of resources and of the revenues from their use. Regionalism, as a factor in Russian politics which took shape in the second half of the 1990s, has a powerful potential; attempts to restrain this factor by depriving the regions of political representation (the way it was done in the 2000s) can be only temporary and can cause a recoil in the future.

Remarkably, the issue of effective autonomy of the regions has been one of the few – and likely to be the only one – political issues over which public opinion differed fundamentally from that of the central government already in the late 2000s. According to the polls, throughout the second half of the 2000s, 60-65 percent of respondents consistently expressed support for resuming the election of regional governors, and only 25-30 percent supported the official position that upholds the current system of governors’ appointment by the president. This distribution of responses is typical of situations when people are asked general questions like “What kind of system do you think is better?” However, when people are asked whether they want their governor or mayor to be elected by popular vote or appointed by a higher authority, the number of supporters of direct elections grows to 75-80 percent, while the number of supporters of appointment falls to 8-15 percent (surveys by the Levada Center in Moscow and Perm in 2010, www.levada.ru). Clearly, as soon as there is a weakening of the central government’s position, the issue of governors’ election will return to the political agenda. Moreover, this issue becomes an ideal focal point for consolidation of dissent and passive dissatisfaction, as well as a point of intersection of the interests of the regional elites and public disillusionment with the policies of the central government.

Internal regional conflicts, i.e., conflicts between appointed governors and local elites, have the greatest potential for politicization of society, linking together the regional (local) and federal political arenas. This was graphically demonstrated by the events in Kaliningrad in early 2010. The conflict between part of the regional elite and the governor, Georgy Boos, who had been appointed by Moscow, led to a massive rally at which demands for the resignation of Prime Minister Putin were voiced. This situation highlighted the political risks that the appointed governors carry for the central government amid the deteriorating economic situation: a purely internal regional conflict turns into regional opposition to the center, and causes an escalation of distrust of the federal government’s policies in general.

The list of trouble issues that can generate conflicts with broad implications is long enough. Let me mention just one more – the high probability of a crisis of corporate management in major companies (regardless of whether the main shareholder is the state or a private entity). The influence of the nominal owners on the activity of such companies has weakened in recent years, and the influence of management has grown, while the mechanisms of external control have been poorly arranged. In the favorable situation of recent years these companies existed in a state of constant expansion, relying both on the political support from the government and on the high availability of external financing. As a result, the companies have effectively operated under soft budget constraints, justifying them with hopes for future profits. Changes in the external conditions, coupled with reduced demand, may lead to a sharp deterioration in their financial situation. It should be noted that these companies are acting today as the central government’s “wallets” paying for the political infrastructure of “soft authoritarianism.” In such a situation the conflicts of interests of different levels of a company’s management may quickly spread into “politics,” causing the infrastructure’s erosion.

In this case, however, the specific points of “bifurcation” are not as important as the systemic causes that give rise to them. When the phase of restorative growth and the period of overheating associated with the significant influx of foreign capital ends and conditions of “difficult growth” and, correspondingly, of lower growth rates emerge, the tools of “manual control” and excessive centralization will reveal their glowing inefficiency.

THE BASELINE SCENARIO: A RETURN TO THE FUTURE

If one is to conceptualize the theoretical framework of Russian institutions with regard to the coming decade, it is worth remembering that in forecasting possible scenarios for development, an inertial scenario usually implies a linear extension of existing trends. My attempt to examine the forthcoming period in the context of the two preceding cycles – transformation and stabilization – allows to study the issue from a somewhat different perspective. The transition from the first cycle to the second one looks as a sharp and deep turnaround in terms of both economic and social trends – as a radical rejection of the previous period. However, the logic of economic processes – much like the logic of social expectations and preferences – and the general “agenda” of the second cycle appear to be largely exhausted today. In this regard, as the inertial scenario for the 2010s, we anticipate some sort of general reverse motion – a partial return, on a new level – to the preferences and the agenda of the 1990s.

My analysis is also based on the assumption that the deterioration of economic behavior will impact not only the population, but also (and primarily) the elite, who are currently tied by the rules of the “imposed consensus.” This means that the diffusion of the current political system could take place against the background of economic changes that, at first glance, do not look like a crisis. The system of political and economic interactions prevailing in Russia today is very young, being formed “on the spot” in an extremely favorable external environment. Its ability to adapt to other economic conditions is unknown, and the impulses that enabled its formation appear to have been largely squandered.

Thus, I will list main conclusions:

- the reaction to the transformations of the early 1990s that had formed in public opinion in the previous period (1993-1998) gave impetus to the movement in the opposite direction;

- the economic growth in the 2000s provided significant support to the consolidation of new political practices consistent with the values of order, stability and recentralization;

- at the same time, in public opinion in the 2000s, the strength of the preferences for the values expressed in these practices gradually weakened and the relevance of these values declined, while signs of demand for more balanced political mechanisms began to surface;

- the crisis and the subsequent long slowdown or cessation of economic growth will stimulate demand for alternative models of political and social organization; the idea of centralization will quickly – and the idea of “stability” will more slowly – lose value in the eyes of society;

- the deterioration of economic conditions will lead to the erosion and collapse of the regime of the “imposed consensus” in the relations among the elites, while inter-elite conflicts will again break into the public arena.

This inertial baseline scenario is unlikely to be altered by some separate efforts of domestic players – for example, by tightening censorship and political control, exerting pressure on the opposition, or further centralizing the mechanisms of control. Such measures taken amid a weak economic situation (and the probability that they will be taken in the near future seems to be high) either will have no effect, or will lead to an escalation of the basic contradictions between old political and administrative practices and new public demand. As it usually happens during the declining years of a political trend, even accidental events – such as natural and man-made disasters – will play against it. New shocks in the commodity markets are capable of quickly turning the scenario into a crisis.

In order to alter the baseline scenario, events will have to take place that once again will make society support a mobilizing agenda. In the 1990s, the war in the Caucasus played the role of an external stimulus that secured support for such an agenda. However, such events, if repeated, will inflict a heavy blow on the government’s reputation as the “guarantor of stability.”

The exhaustion of the potential of the previous model of economic growth signals not only that the country badly needs a new model, but also that it will have to make amendments concerning prevailing social attitudes, assessments and expectations, while the elite groups will have to rethink their possibilities and strategies. These amendments and their social and political consequences will largely determine the content and trajectory of the third cycle of Russia’s post-Soviet history.